I have never read a review of a play by Samuel Beckett in which the reviewer’s ignorance of Beckett’s fiction was not made clear.

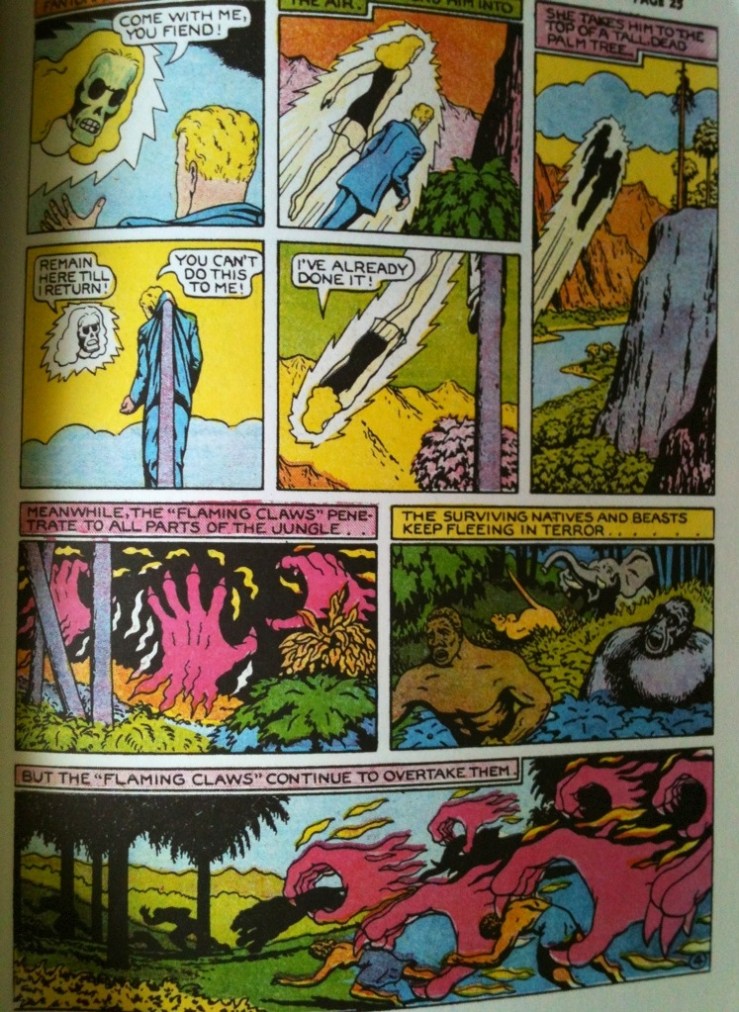

All popular culture is essentially the same, i.e., it cannot transcend its audience-attentive whatness, nor can it escape the universe of camp toward which it is pointed at the moment of its birth. Lawrence Welk really is the same as Mick Jagger and “Saturday Night Live” the “Ed Sullivan Show”‘s other face.

No fatal disease is privileged, and all disease is as natural as health. To believe otherwise is to believe that we are “supposed to” die in a certain, “reasonable” way, sans pain and sadness. This attitude toward mortality makes for a lot of misery.

That Charles Olson made indisputably great poetry does not obviate the fact that he was also the Wizard of Oz.

There are few things more disgusting than a superior, mocking, self-important review of a trashy book by a hack writer.

Abstract love and generalized compassion increase in direct proportion to organized social viciousness.

Frank O’Hara is the saddest of all postwar American poets.

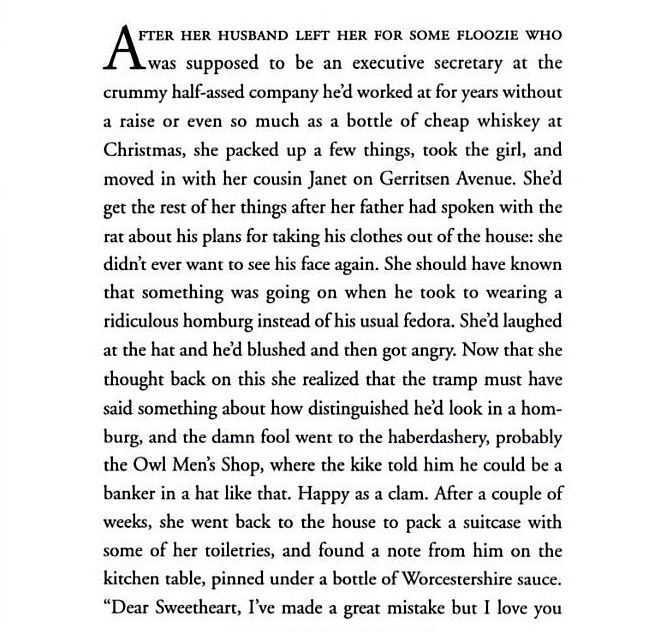

My father didn’t speak English until he was eleven, at which time he left school and went to work on the Brooklyn waterfront. His letters, despite an occasional spelling error or grammatical gaffe, are written in a better prose than can be managed by most of the university undergraduates I’ve taught. He was far from unique.

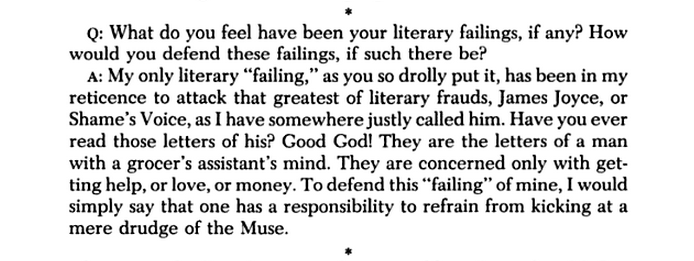

If, as Goethe’s Mephistopheles says, all theory is gray, theory concerning theory is Joycean brown.

Artists who pretend that they are no more than workers in the arts are neither artists nor workers.

To say that most book reviewers are lazy, illread and addicted to the banal is like saying “war is hell” or “greed is the root of evil.” These remarks hide their truths behind the deadening familiarity of their verbal representations; but they are truths nevertheless.

Popular art reflects and flatters popular culture, or, if you prefer, the Zeitgeist. In retrospect, it sometimes seems as if it leads and influences the true culture, or the innate wisdom of a people, but this isn’t so.