Seventeen-year-old Mari, the narrator and subject of Yoko Ogawa’s new novel Hotel Iris, is something of a Cinderella figure. Her dad dies a violent death when she is only eight years old and her grandparents soon pass on as well, leaving her in the sole custody of her money-grubbing mother who works poor Mari like a slave in the upkeep of their shabby hotel. The titular Iris is a crumbling structure with only one seaside view, frequented in the off-season by prostitutes and only bustling in the sweltering summer months. It’s in the off-season when Mari first spies the transformative figure in her life–a man fifty years her senior who gets into a raucous fight with a hooker in the hotel. Transfixed by his commanding voice, Mari follows the man the next day as he performs banal errands. When he confronts her, the two strike up a strange friendship (very strange, it will turn out). The man lives on a small island where he works translating mundane Russian texts like tourist pamphlets–although he is hard at work at a passion project, translating a strange Russian novel. The translator begins writing Mari letters and she eventually sneaks away to meet him. In the seaside town he treats her with quiet deference, but when Mari visits his small, austere home on the island she undergoes a bizarre, sadistic sexual awakening. To continue a proper review of Hotel Iris will necessitate some mild spoilers. I won’t reveal any major plot points, but those intrigued may wish to stop reading here. Otherwise, on to the aforementioned bizarre, sadistic sexual awakening.

It’s pretty simple, really. The translator, a sexual sadist, has found in Mari a perfect masochist, a young girl so alienated and lonely that she can only find pleasure in extreme pain, beauty in brutal ugliness, and freedom in bondage. Her initial attraction to the translator, his commanding voice, goes to extremes in his isolated house on the island, where he strips her naked, ties her up, and forces her into all sorts of sexual humiliations. In a strange mirror of her Cinderella-life at Hotel Iris, he forces her to clean his house while strapped to a chair. He takes thousands of degrading photographs of her. In a scene reminiscent of “Bluebeard” he hangs her from the ceiling of a tiny pantry and whips her with a riding crop. He never engages in direct coitus with her; in fact, he never even removes the suit and tie he wears even in the sweltering summer. In each scenario Mari expresses the true happiness and pleasure she finds in the translator’s torture. “Only when I was brutalized, reduced to a sack of flesh, could I know pure pleasure,” she tells us.

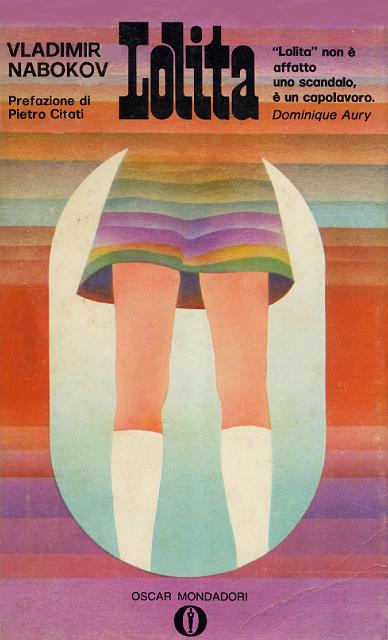

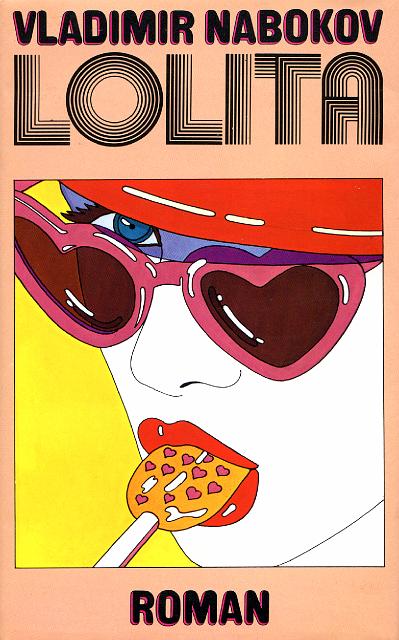

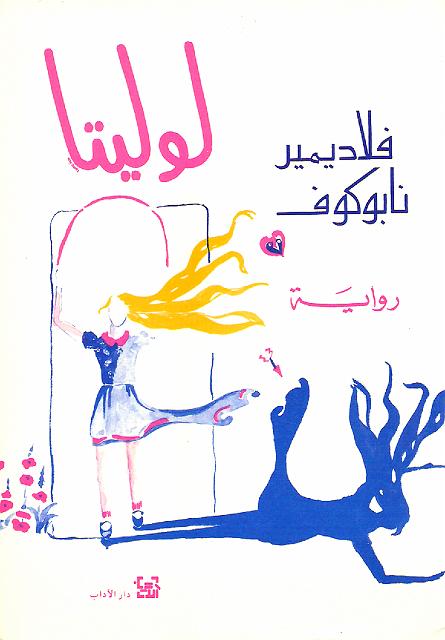

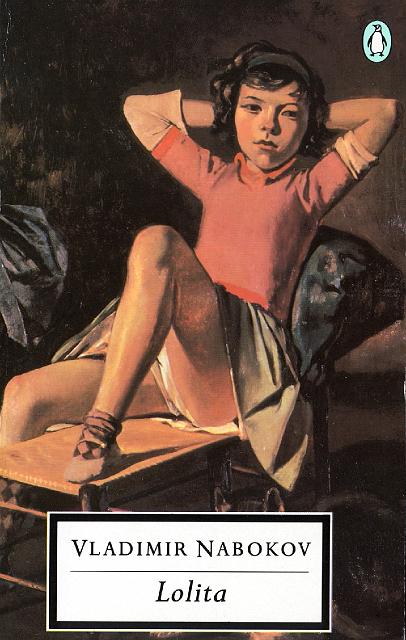

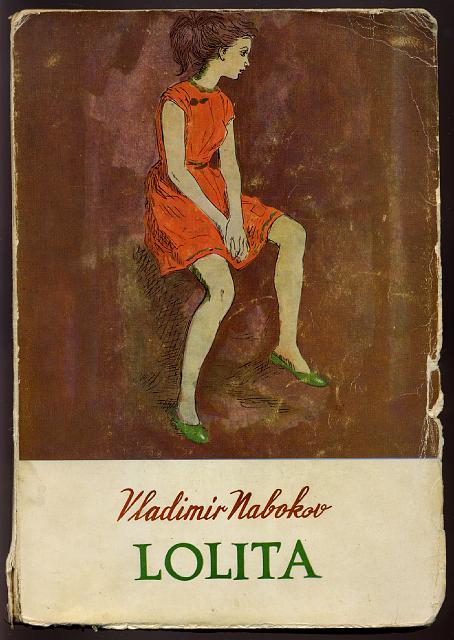

That young, naïve Mari should narrate the novel is the genius of Ogawa’s program. Her first-person immediacy communicates the confusion and despair of a neglected, overworked teen trapped in a dead-end job in a Podunk town. As the plot spirals it tempts the reader to endorse the “love” that Mari feels for the old man who tortures her. Just as Nabokov manipulates his readers via the charms of Humbert Humbert, Ogawa, writing her reverse-Lolita, repeatedly cons us into normalizing the relationship, in viewing it only from Mari’s perspective. It’s through the slipped, oblique details of Mari’s past that we construct a more coherent image of a long pattern of abuse. Her mother, always bragging about Mari’s beauty, tells the story of a sculptor who used Mari as a model (Mari, of course, believes herself ugly). “The sculptor was a pedophile who nearly raped me.” The only maid in the hotel repeatedly claims to be “like a mother” to Mari, yet she attempts to blackmail and humiliate the poor girl, and even tells her that she was Mari’s father’s “first lover.” Late in the novel, a drunken hotel guest gropes Mari’s breast and her mother brushes the abuse off, blaming implicitly on her daughter. The focused, purposeful sadism of the translator–a result of the man’s own painful past–is thus a form of love for Mari. Yet we see what Mari can’t see, even as we accept the savage doom of their romance.

Hotel Iris recalls the dread creepiness of David Lynch, as well as that director’s subversion of fairy tale structures (perhaps “subversion” is not the right word–aren’t fairy tales by nature subversive?). There are also obvious parallels between Mari’s story and The Story of O and Peter Greenaway’s fantastic film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, & Her Lover. But these are perhaps lazy comparisons–I should talk about Ogawa’s deft writing, her supple, slippy sentences, her sharpness of details, the exquisite ugliness of her depictions of sex and eating. She’s a very good writer, and translator Stephen Snyder has done a marvelous job rendering Ogawa’s Japanese into smooth, rhythmic sentences that resist idiomatic placeholders. Hotel Iris is not for everyone, but if you’ve read this far you’ve probably figured that out already. Readers who venture into Ogawa’s dark world will find themselves rewarded with a complex text that warrants close re-reading. Recommended.

Hotel Iris, a Picador trade paperback original, is available today.

1962, Brazil.

1962, Brazil.