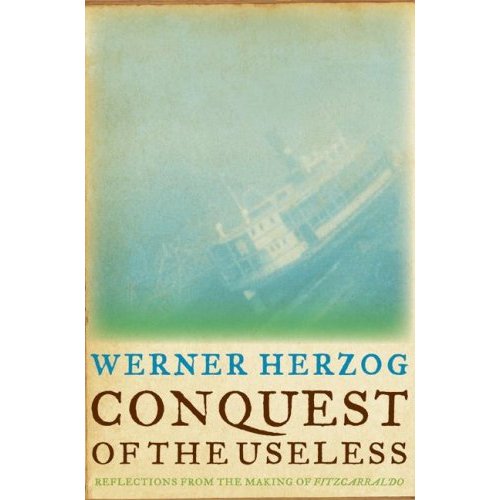

This month’s issue of Harper’s features a fantastic collection of diary entries by German film director Werner Herzog. These entries are excerpted from the forthcoming book Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo. Released in 1982, Fitzcarraldo tells the story of a would-be rubber magnate who attempts to haul a steamship over a small mountain in Peru so that he can access an area rich in rubber trees. The infamous Klaus Kinski plays Fitzcarraldo, a European who pushes his crew to the breaking point in this mad quest; the semi-fictional plot was doubled in the real-life production disasters that plagued the movie. Fitzcarraldo dramatizes one of the oldest narrative conflicts, man vs. nature, in an earnest yet completely unromantic way. Fitzcarraldo, the opera-lover who brings ice to the natives, shatters any romantic illusions one might have about the power and majesty of nature in his mad schemes. This theme repeats throughout Herzog’s work, from the conquistador opus Aguirre, the Wrath of God to his outstanding 2005 documentary Grizzly Man. Again and again, Herzog’s films ironize, disrupt, or otherwise show the folly of romanticizing nature. His diary entries from Conquest of the Useless lay these sentiments bare in ways both bleakly poetic and terribly funny.

Take this entry from December 8, 1980: “The jungle is obscene. Everything about it is sinful, for which reason the sin does not stand out as sin.” Here, Herzog provides a succinct antithesis to Rousseau’s concept of the “noble savage.” Herzog’s view of man—de-politicized, that is—seems more Hobbesian, actually. In an entry from April 6, 1981, he writes:

“This morning I woke up to terror such as I have never experienced before: I was entirely stripped of feeling. Everything was gone; it was as if I had lost something that had been entrusted to me the previous evening, something I was supposed to take special care of overnight. I was in the position of someone who has been assigned to guard an entire sleeping army, but suddenly finds himself mysteriously blinded, deaf, and effaced. Everything was gone. I was completely empty, without pain, without longing, without love, without warmth and friendship, without anger, without hate. Nothing, nothing was there anymore, and I was left like a suit of armor with no knight inside. It took a long time before I even felt alarmed.”

Nature seems to nullify Herzog, to void any essential humanity he might have had. His repetition of “Nothing, nothing was there anymore” reminds me of King Lear’s famous lines “Never, never, never, never, never.” Although Lear is weeping over the body of his kind daughter Cordelia, the psychology of these lines surely reflect his own terrible experiences, his own nullified identity of homelessness on the wild heath.

For Herzog, nature is a war, nature will eat you. “Moss grows on lianas, and in the knobby places where the moss is thicker, a leafy plant like a slender hare’s ear grows out of the moss: a parasite on a parasite on a parasite,” he observes. If Herzog is melancholy or mordant in these grim reckonings, he’s also very, very funny. Take this hilarious June 4th entry concerning a giant albino turkey that’s been terrorizing the set:

“The camp is silent with resignation; only the turkey is making a racket. It attacked me, overestimating its own strength, and I quickly grabbed its neck, which squirmed and tried to swallow, slapped him left-right with the casual elegance of the arrogant cavaliers I had seen in French Three Musketeers films who go on to prettily cross swords, and then let the vain albino go. His feelings hurt, he trotted away, wiggling his rump but with his wings still spread in conceited display.”

And yet one senses that Herzog’s humor is a defense against the absurdity of nature, one that derives from an acute awareness that humanity is at once of and apart from nature, and at that by its own definition, its own choice. In a June 2nd entry featuring his nemesis the albino turkey, Herzog details an incident that highlights the essential ugliness of a Darwinian world:

“Our kitchen crew slaughtered our last four ducks. While they were still alive, Julian plucked their neck feathers, before chopping off their heads on the execution block. The white turkey, that vain creature, the survivor of so many roast chickens and ducks transformed into soup, came over to inspect, gobbling and displaying, and used his ugly feet to push one of the beheaded ducks, as it lay there on the ground bleeding and flapping its wings, into what he thought was a proper position and making gurgling sounds while his bluish-red wattles swelled, he mounted the dying duck and copulated with it.”

There we go. We get it all, all the order of nature. Food, sex, death, the whole deal, laid out keenly and with grim humor, neatly compacted into a single, grotesque episode. If these excerpts are any indication of the rest of the book’s trajectory, Conquest of the Useless promises to transcend standard making-of fare. Indeed, Herzog’s book seems nothing less than a profound meditation on the intersection of man, nature, terror, and mortality.

Conquest of the Useless: Reflections on the Making of Fitzcarraldo is available June 30th from HarperCollins.