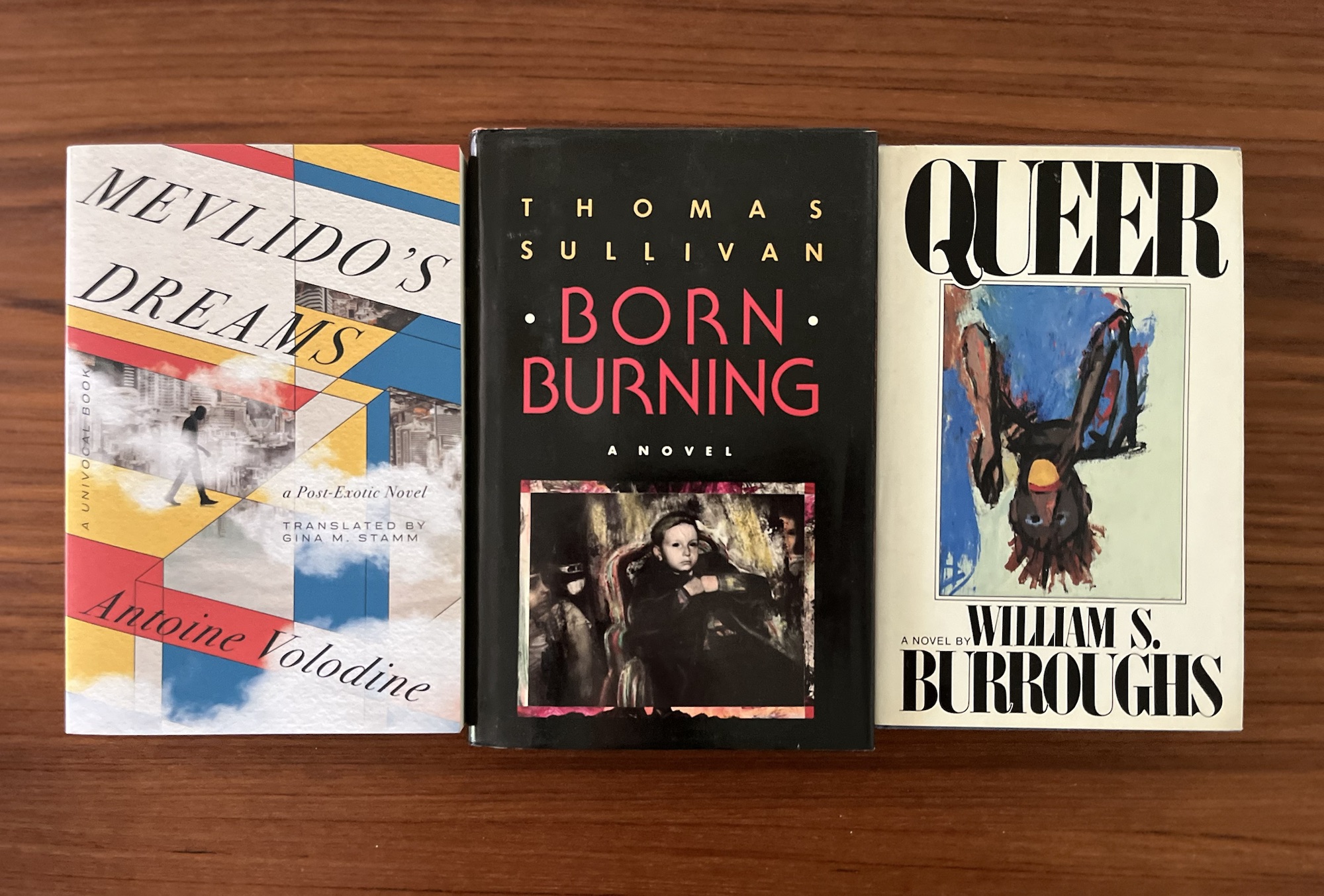

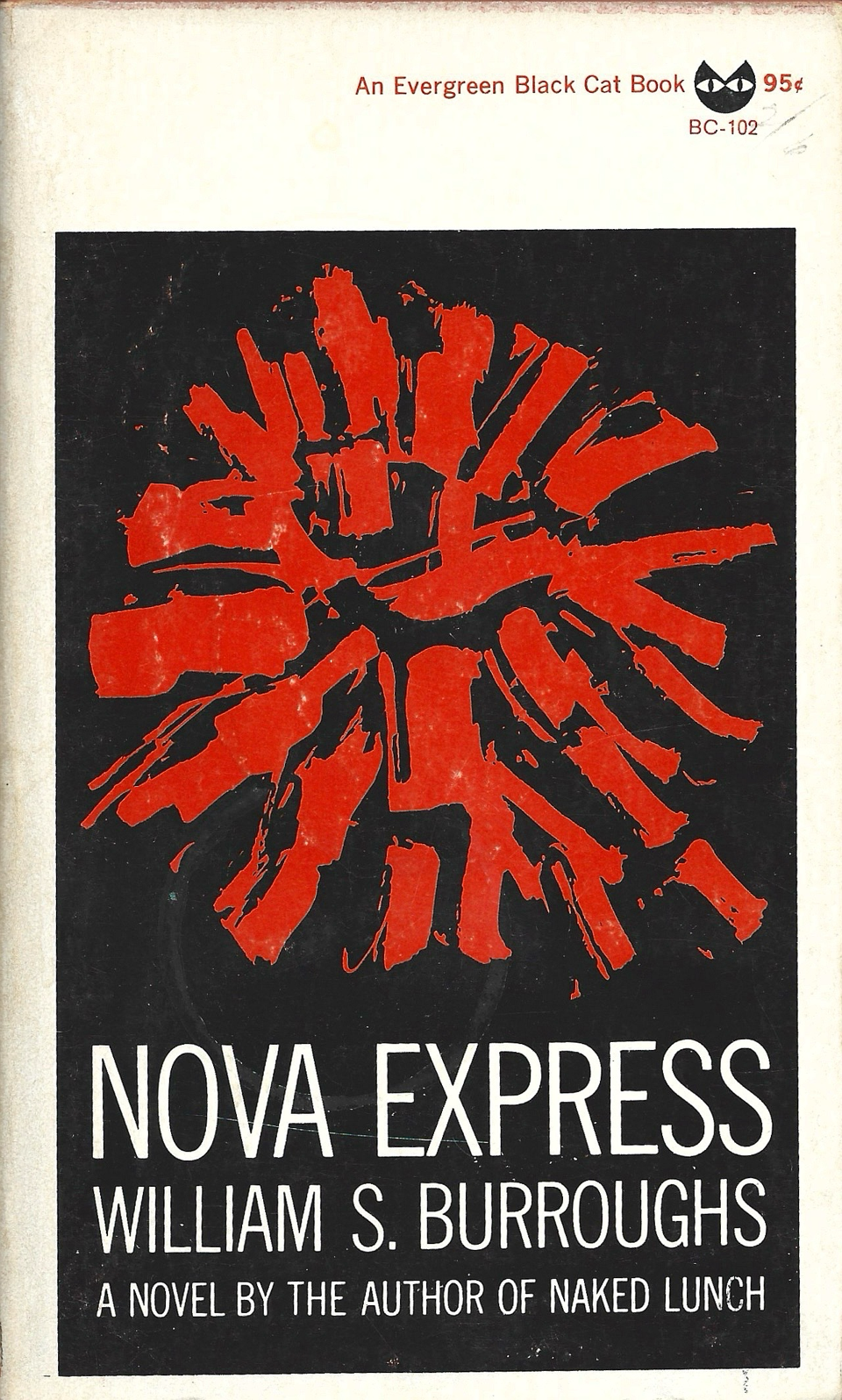

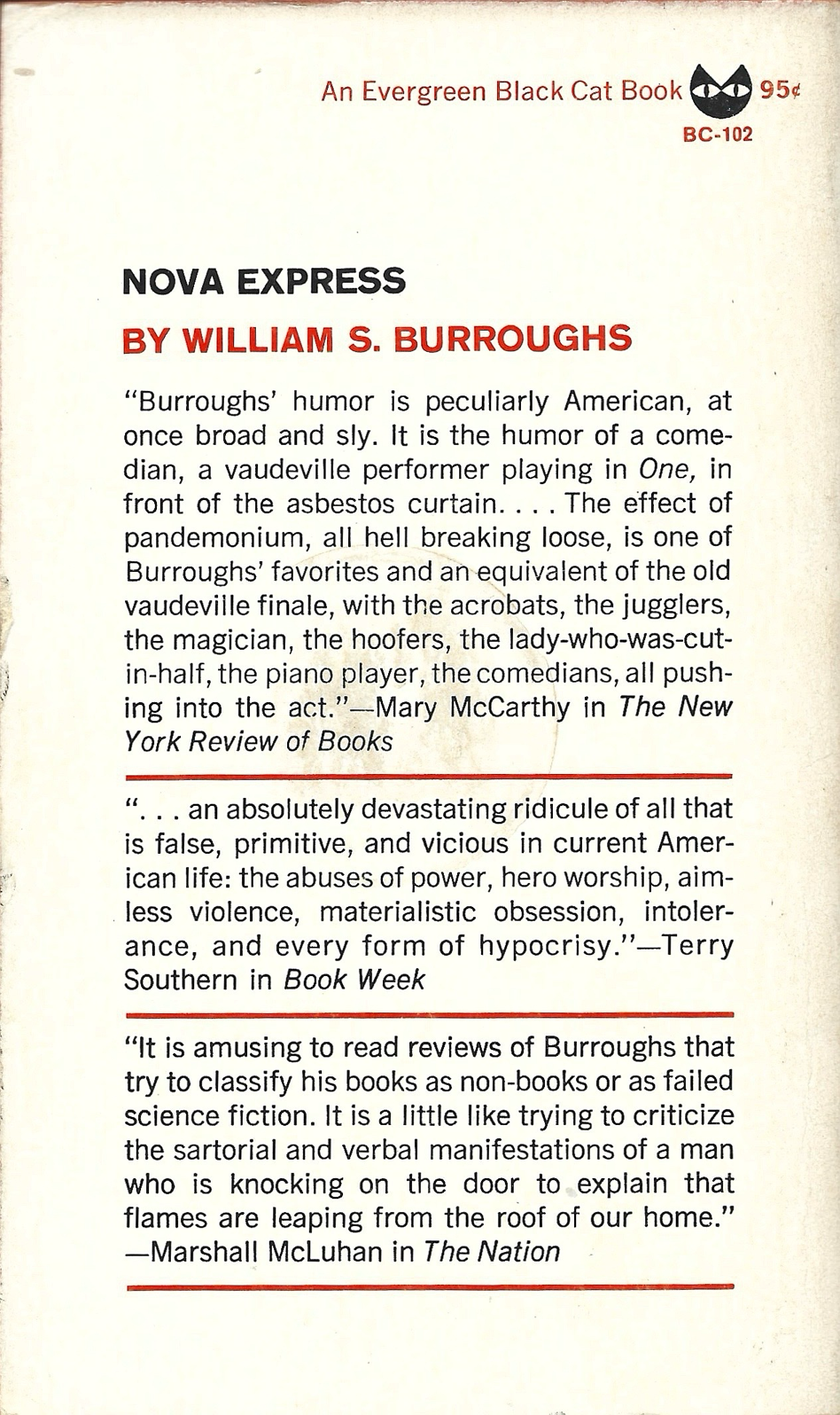

Nova Express, William S. Burroughs, 1964. Evergreen Black Cat Books (1965). 155 pages. The cover by artist Grove Press mainstay Roy Kuhlman is not credited.

I picked up this mass-market Burroughs at A Capella Books in Atlanta this weekend. We drove up on Thursday to see the American indie rock band Big Thief play at the Fox Theatre. The theater is gorgeous, its interior a lavish orientalist fantasy draped in rich reds and golds, royal blues, and warm ambers, all illuminated under a ceiling painted to resemble a twinkling night sky. The sound was pretty bad and the crowd was worse. Several groups around me talked throughout the concert, and the general vibe was soured by the crowd’s inability to pick a lane when it came to standing-or-not-standing. Big Thief started in a moody jammy mood jamming on an extended version of “No Fear” from their new album Double Infinity. They followed it up with three more songs from the new album, and while the playing was polished and strong, with plentiful harmonic textures coming from the guitars, the audience didn’t really respond in a strong way until they played two “hits” back to back — “Vampire Empire” and “Simulation Swarm.” The audience then fell into this weird rhythm of people rising to their feet like reverse dominoes when people closer to the stage decided to stand and sway to more familiar “hits,” only to sit down when Big Thief played a newer song. The jerky rhythm led to hissed arguments and then not-so-hissed arguments throughout the theater — again, the mood was really odd, and the band didn’t seem to really connect with the audience. At one point, guitarist Buck Meek said something like, “You can dance to this new one, too” — but the few people who tried eventually quit. After “Not” and “Masterpiece,” Big Thief decided to workshop a new song, stopping at one point to adjust the rhythm. Again, the reaction to this tinkering was mixed. The highlight of the show for me was a dreamy, hazy, heavy reworking of “Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe in You” in which the band seemed to tune totally in to their sound. (I had also managed to get the guys behind me to shut the fuck up after a very tense exchange, so I could actually appreciate the sounds without their banal chomping.) The band managed to get the crowd on their feet two more times — once with “Spud Infinity” near the end of their set, and then again when the crowd called for the obligatory encore. (It’s worth noting that much of the crowd headed to the exits right away, determined to beat awful Atlanta traffic.) Big Thief then played exactly one song (“Change”) and left, signalling for the house lights to come on. I have never seen a band play only one song at an encore. Some of the people I was with had a better time than I did. The show mostly reminded me of seeing Wilco in an old theater — this was close to twenty years ago, I guess — and their failure to connect with the audience. There’s not a lot of room to boogie in those old seats. That’s not what a theater is designed for. I saw Yo La Tengo around the same time in the same theater and they absolutely understood the space they were playing in and mapped their show around it. I still have a sour taste in my mouth from the concert, but the rest of the weekend was fun–good food, good times, etc. I even dressed up for Halloween — as Bob Ferguson from One Battle After Another. It’s such an easy costume (jeans, flannel robe, black beanie, oversized sunglasses) that I thought the Beltline would be littered with other lazy dickheads with the same dickhead idea, but it wasn’t. Everyone I interacted with thought I was going for the Dude. In my review of One Battle After Another I made the bathrobe connection writing that PTA’s film plays “as a sinister inversion to The Big Lebowski. I will file the pair away for a future double feature.” Later that night, after perhaps too many okay not perhaps definitely too many libations I rewatched The Beach Bum on my laptop. That’s the triple feature — Battle, Lebowski, Bum.

So here’s a snippet from Nova Express, just so I won’t be accused of bait n’ switch:

“Mr. Martin, and you board members, vulgar stupid Americans, you will regret calling in the Mayan Aztec Gods with your synthetic mushrooms. Remember we keep exact junk measure of the pain inflicted and that pain must be paid in full. Is that clear enough Mr. Intolerable Martin, or shall I make it even clearer? Allow me to introduce myself: The Mayan God Of Pain And Fear from the white hot plains of Venus which does not mean a God of vulgarity, cowardice, ugliness and stupidity. There is a cool spot on the surface of Venus three hundred degrees cooler than the surrounding area. I have held that spot against all contestants for five hundred thousand years. Now you expect to use me as your ‘errand boy’ and ‘strikebreaker’ summoned up by an IBM machine and a handful of virus crystals? How long could you hold that spot, you ‘board members’? About thirty seconds I think with all your guard dogs. And you thought to channel my energies for ‘operation total disposal’? Your ‘operations’ there or here this or that come and go and are no more. Give my name back. That name must be paid for. You have not paid. My name is not yours to use. Henceforth I think about thirty seconds is written.”