“The Bet” by Anton Chekhov

I

It was a dark autumn night. The old banker was pacing from corner to corner of his study, recalling to his mind the party he gave in the autumn fifteen years before. There were many clever people at the party and much interesting conversation. They talked among other things of capital punishment. The guests, among them not a few scholars and journalists, for the most part disapproved of capital punishment. They found it obsolete as a means of punishment, unfitted to a Christian State and immoral. Some of them thought that capital punishment should be replaced universally by life-imprisonment.

“I don’t agree with you,” said the host. “I myself have experienced neither capital punishment nor life-imprisonment, but if one may judge a priori, then in my opinion capital punishment is more moral and more humane than imprisonment. Execution kills instantly, life-imprisonment kills by degrees. Who is the more humane executioner, one who kills you in a few seconds or one who draws the life out of you incessantly, for years?”

“They’re both equally immoral,” remarked one of the guests, “because their purpose is the same, to take away life. The State is not God. It has no right to take away that which it cannot give back, if it should so desire.”

Among the company was a lawyer, a young man of about twenty-five. On being asked his opinion, he said:

“Capital punishment and life-imprisonment are equally immoral; but if I were offered the choice between them, I would certainly choose the second. It’s better to live somehow than not to live at all.”

There ensued a lively discussion. The banker who was then younger and more nervous suddenly lost his temper, banged his fist on the table, and turning to the young lawyer, cried out:

“It’s a lie. I bet you two millions you wouldn’t stick in a cell even for five years.”

“If you mean it seriously,” replied the lawyer, “then I bet I’ll stay not five but fifteen.”

“Fifteen! Done!” cried the banker. “Gentlemen, I stake two millions.”

“Agreed. You stake two millions, I my freedom,” said the lawyer.

So this wild, ridiculous bet came to pass. The banker, who at that time had too many millions to count, spoiled and capricious, was beside himself with rapture. During supper he said to the lawyer jokingly:

“Come to your senses, young roan, before it’s too late. Two millions are nothing to me, but you stand to lose three or four of the best years of your life. I say three or four, because you’ll never stick it out any longer. Don’t forget either, you unhappy man, that voluntary is much heavier than enforced imprisonment. The idea that you have the right to free yourself at any moment will poison the whole of your life in the cell. I pity you.”

And now the banker, pacing from corner to corner, recalled all this and asked himself:

“Why did I make this bet? What’s the good? The lawyer loses fifteen years of his life and I throw away two millions. Will it convince people that capital punishment is worse or better than imprisonment for life? No, no! all stuff and rubbish. On my part, it was the caprice of a well-fed man; on the lawyer’s pure greed of gold.” Continue reading ““The Bet” — Anton Chekhov”

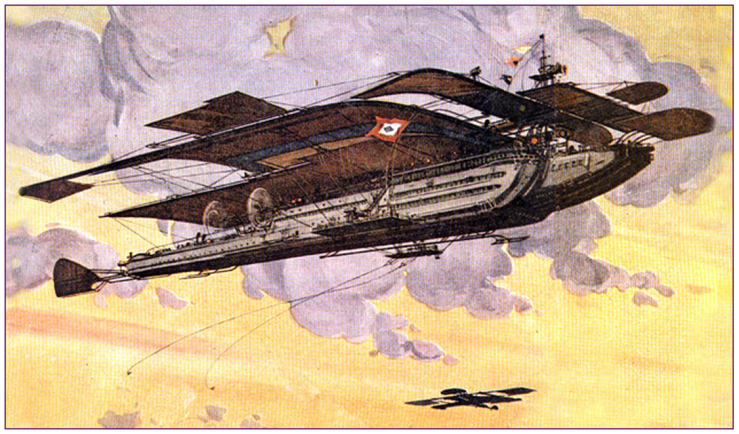

Titles of The Chums of Chance books mentioned in Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day:

Titles of The Chums of Chance books mentioned in Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day: