Tag: John Keats

Isabella and the Pot of Basil — William Holman Hunt

And she forgot the stars, the moon, and sun,

And she forgot the blue above the trees,

And she forgot the dells where waters run,

And she forgot the chilly autumn breeze;

She had no knowledge when the day was done,

And the new morn she saw not: but in peace

Hung over her sweet Basil evermore,

And moisten’d it with tears unto the core.

–John Keats, Isabella, or The Pot of Basil

Three Books

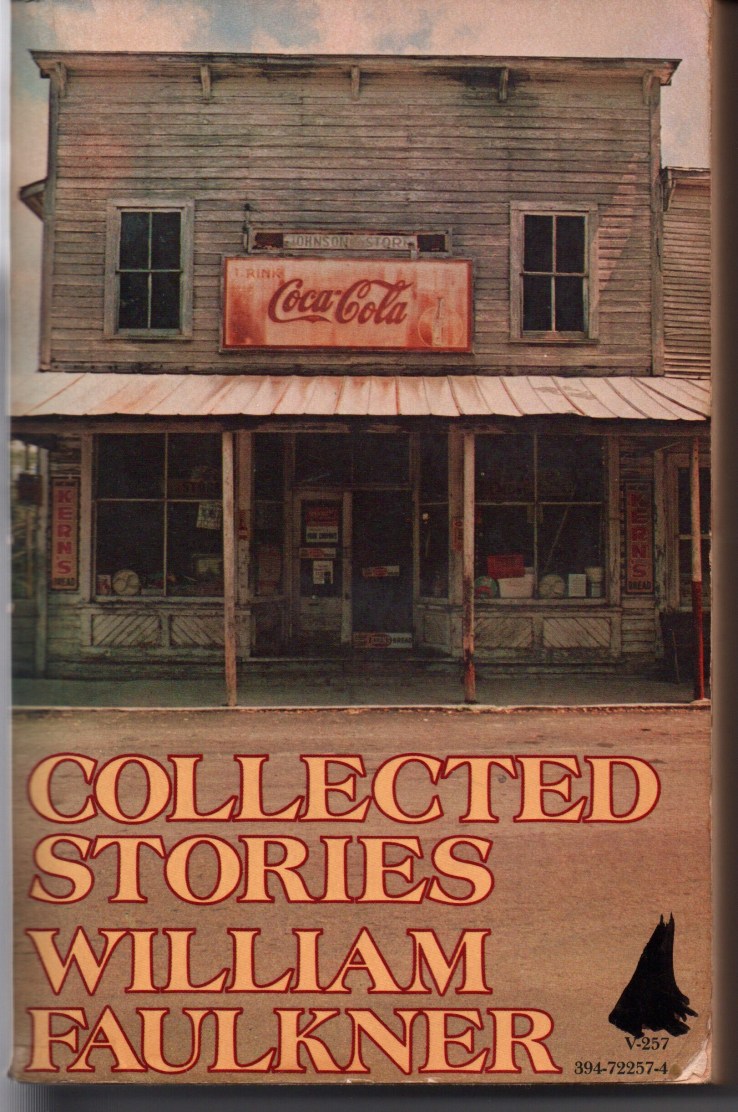

Collected Stories by William Faulkner. 1977 first edition trade paperback from Vintage. This book is 900 pages, exactly, not including the ancillary pages that detail publication dates and rights, as well as Vintage’s back catalog—and yet not one of those pages manages to credit the cover designer or photographer.

I’ve been reading/re-reading this very slowly, with the loose goal of finishing this year.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Vol. 4 by Hayao Miyazaki. English translation by David Lewis and Toren Smith. Studio Ghibli Library edition by Viz Media, 2010. No designer credited, but the cover is by Miyazaki and I imagine we can probably credit Studio Ghibli with the design.

I started rereading Nausicaä this week after revisiting Princess Mononoke this week. Then I got horribly ill, and the only stuff I can really read when I’m really sick are comics. I scanned Vol. 4 for this week’s Three Books post; I finished it pretty late last night. Vol 5-7 remain.

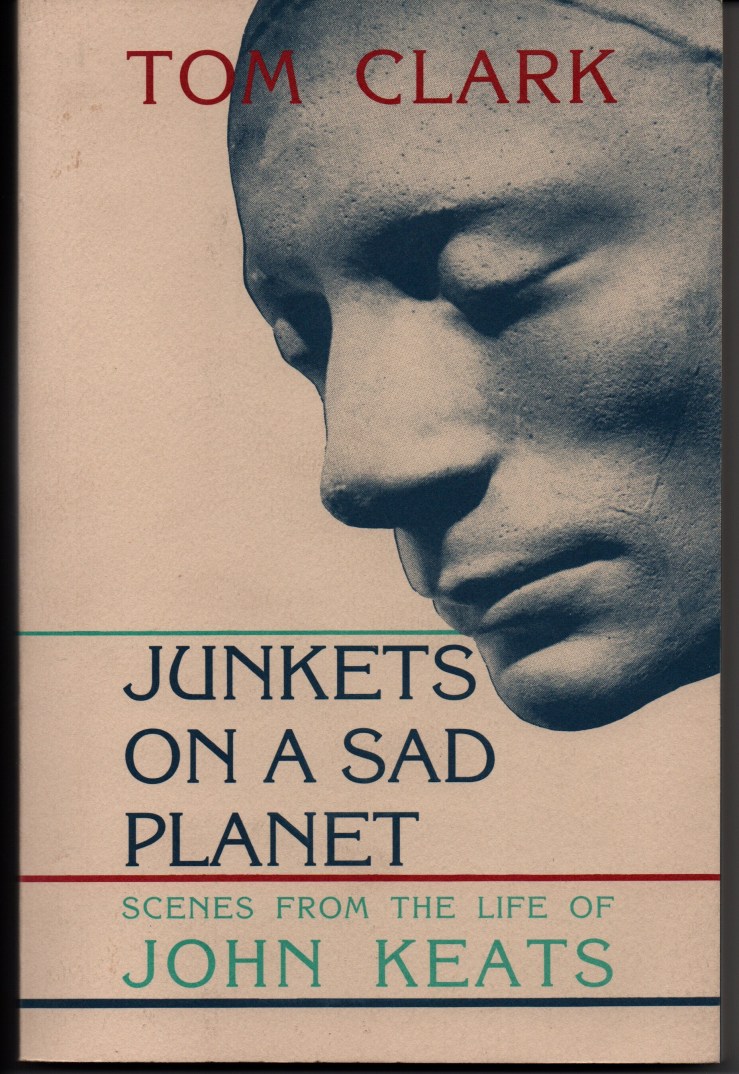

Junkets on a Sad Planet by Tom Clark. First edition trade paperback by Black Sparrow Press, 1994. Cover design by Barbara Martin. The image is of Benjamin Robert Haydon’s life mask for John Keats (from a photo by Christopher Oxford).

I awoke around 1am in the middle of last week, and unable to sleep, I wandered to our den and randomly took this from the shelf to begin reading/rereading. The book (its title is a pun) is difficult to explain, a beautiful experience, rich. Here’s Clark’s own description: “…an extended reflection on the modern poet’s life, as Keats lived it. The book may be read by turns as poetic novel, biography in verse, allegorical masque, historical oratorio for several voices.”

“When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” — John Keats

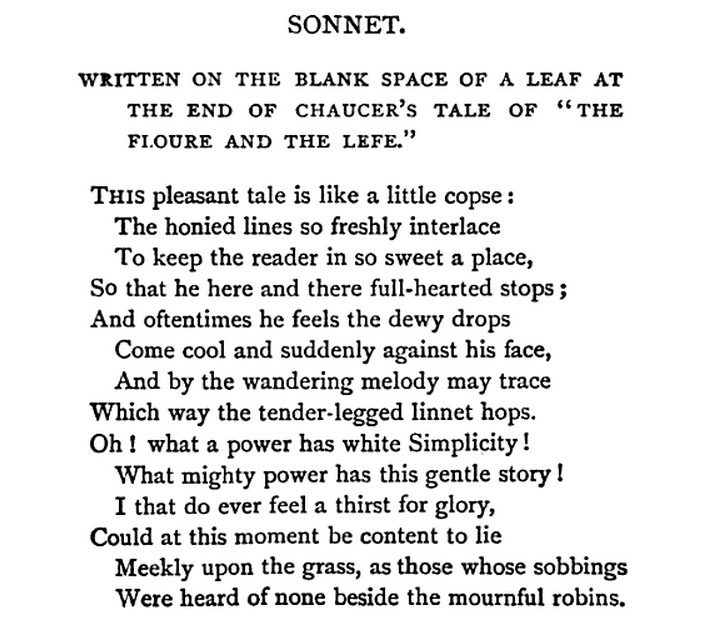

“Written on the Blank Space of a Leaf at the End of Chaucer’s Tale of ‘The Floure and the Lefe'” — John Keats

“In drear-nighted December” — John Keats

“In drear-nighted December” by John Keats

In drear-nighted December,

Too happy, happy tree,

Thy branches ne’er remember

Their green felicity:

The north cannot undo them

With a sleety whistle through them;

Nor frozen thawings glue them

From budding at the prime.In drear-nighted December,

Too happy, happy brook,

Thy bubblings ne’er remember

Apollo’s summer look;

But with a sweet forgetting,

They stay their crystal fretting,

Never, never petting

About the frozen time.Ah! would ’twere so with many

A gentle girl and boy!

But were there ever any

Writhed not at passed joy?

The feel of not to feel it,

When there is none to heal it

Nor numbed sense to steel it,

Was never said in rhyme.

More Tom Clark (Books Acquired, 11.16.2013)

Last week I picked up more Tom Clark books. Devouring these things. I lied to myself that I was buying Paradise Resisted for a friend (I didn’t give it to him; I did give him a copy of Blood Meridian though). Junkets on a Sad Planet is a Very Strange Book.

A poem from Paradise:

World of Pains and Troubles (John Keats)

—The common cognomen of this world among the misguided and superstitious is ‘a vale of tears’ from which we are to be redeemed by a certain arbitrary interposition of God and taken to Heaven–What a little circumscribed straightened notion! call the world if you Please ‘The vale of Soul-making’ Then you will find out the use of the world (I am speaking now in the highest terms for human nature admitting it to be immortal which I will here take for granted for the purpose of showing a thought which has struck me concerning it) I say “Soul making” Soul as distinguished from an Intelligence– There may be intelligences or sparks of the divinity in millions–but they are not Souls till they acquire identities, till each one is personally itself. Intelligences are atoms of perception–they know and they see and they are pure, in short they are God–how then are Souls to be made? How then are these sparks which are God to have identity given them–so as ever to possess a bliss peculiar to each ones individual existence? How, but by the medium of a world like this? This point I sincerely wish to consider because I think it a grander system of salvation than the chrystain religion–or rather it is a system of Spirit-creation–This is effected by three grand materials acting the one upon the other for a series of years–These Materials are the Intelligence–the human heart (as distinguished from intelligence or Mind) and the World or Elemental space suited for the proper action of Mind and Heart on each other for the purpose of forming the Soul or Intelligence destined to possess the sense of Identity. I can scarcely express what I but dimly perceive–and yet I think I perceive it–that you may judge the more clearly I will put it in the most homely form possible–I will call the world a School instituted for the purpose of teaching little children to read–I will call the Child able to read, the Soul made from that school and its hornbook. Do you not see how necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a soul? A Place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways! Not merely is the Heart a Hornbook, it is the Minds Bible, it is the Minds experience, it is the teat from which the Mind or intelligence sucks its identity–As various as the Lives of Men are–so various become their Souls, and thus does God make individual beings, Souls, Identical Souls of the sparks of his own essence–“

—From a letter John Keats wrote to his brother George, dated April 21, 1810. (More excerpts from Keats’s letters with commentary).

“Lines” — John Keats

John Keats’s Handwritten Manuscript for “To Autumn”

“To Some Ladies” — John Keats

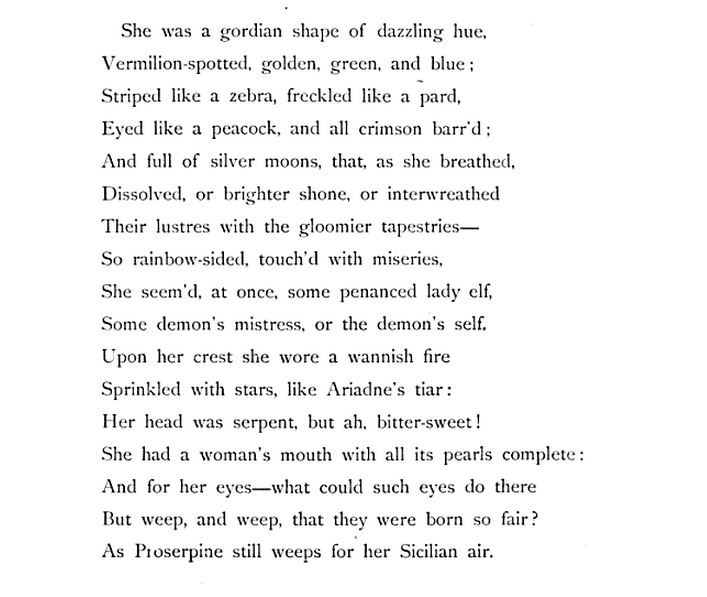

“A Gordian Shape of Dazzling Hue” (Keats’s Lamia)

“On Leaving Some Friends At An Early Hour” — John Keats

“On Leaving Some Friends At An Early Hour” by John Keats—-

Give me a golden pen, and let me lean

On heaped-up flowers, in regions clear, and far;

Bring me a tablet whiter than a star,

Or hand of hymning angel, when ’tis seen

The silver strings of heavenly harp atween:

And let there glide by many a pearly car

Pink robes, and wavy hair, and diamond jar,

And half-discovered wings, and glances keen.

The while let music wander round my ears,

And as it reaches each delicious ending,

Let me write down a line of glorious tone,

And full of many wonders of the spheres:

For what a height my spirit is contending!

‘Tis not content so soon to be alone.

John Keats’s Death Mask

Bright Star — Campion Does Keats

So I finally got around to watching Jane Campion’s Bright Star last night, a film that quietly studies the final years of Romantic poet John Keats and his relationship with Fanny Brawne. When Keats moves next door to the Brawnes, eldest daughter Fanny, a talented seamstress and flighty flirt, soon becomes intrigued by the poet. Keats, with his love for beauty and truth, represents a world of greater depth than the wits and dandies who usually attempt to court Brawne. Their relationship is, of course, doomed from the outset. Perpetually broke Keats doesn’t have the moolah or means to properly engage Brawne in marriage, but that doesn’t stop the pair from undertaking a furtive, pensive love affair, carried out in long walks on the heath and passionate letters. Oh, and Keats gets sick and dies at 25. That shouldn’t be a spoiler if you’ve studied your Romantics properly, now should it?

Both Abbie Cornish who plays Brawne and Ben Whishaw who plays Keats are excellent in their understatement and reserve, but the standout turn in the movie comes from actor Paul Schneider (from NBC’s Parks & Recreation) who plays Keats’s bankrolling friend Charles Armitage Brown. Brown is a lesser poet whose love and envy of Keats leads him to vex Brawne and Keats’s love at every turn, plaguing them with doubt, and that enemy of Romance, Reason. Schneider invests his character with a boorish charm that never veers into the rote tropes that afflict modern romance film. It’s emblematic of the Campion’s film in a way: Bright Star has every opportunity to devolve into a mundane exercise in doomed romance or a stuffy period piece, but under Campion’s delicate care it manages to match the depth of its subject matter.

Campion wrote the screenplay, presumably using letters from the principals as her primary source. She honors her viewers’ intelligence — far too rare these days — by never cobbling her plot together with easy exposition or forced narrative developments, and it’s that sense of history that lends the film authenticity. Cornish’s Brawne is a protagonist whose personality transformations read as real, and Whishaw’s Keats is never a cartoonish mystic or a moody caricature, but a fully-drawn human. Campion also has the good judgment to let her cinematography convey her story, letting gorgeous shots of the English countryside and cloistered chambers alike convey the mood and rhythm of her story. At times, Bright Star‘s beautiful camerawork recalls Terrence Malick, another director who allows film to “happen” to the viewer as an evocative experience rather than a spoon-feeding. Campion also shows considerable restraint with the film’s wonderful score, never allowing it to color a scene unduly when her actors can do a great job on their own. Bright Star avoids all of the pitfalls that might afflict a period piece, and does a far better job handling the subject of Romantic poetry than a movie has any right to. The film is hardly for everyone (sorry guys, no Jason Statham), but it’s very, very good. Recommended.