Watching (again) Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film There Will Be Blood last night, it struck me that the film can be read as an expansion of the epilogue to Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 novel Blood Meridian.

Here is that infamously perplexing passage, a strange note that punctuates the devastating infanticidal horror at the novel’s core:

In the dawn there is a man progressing over the plain by means of holes which he is making in the ground. He uses an implement with two handles and he chucks it into the hole and he enkindles the stone in the hole with his steel hole by hole striking the fire out of the rock which God has put there. On the plain behind him are the wanderers in search of bones and those who do not search and they move haltingly in the light like mechanisms whose movements are monitored with escapement and pallet so that they appear restrained by a prudence or reflectiveness which has no inner reality and they cross in their progress one by one that track of holes that runs to the rim of the visible ground and which seems less the pursuit of some continuance than the verification of a principle, a validation of sequence and causality as if each round and perfect hole owed its existence to the one before it there on that prairie upon which are the bones and the gatherers of bones and those who do not gather. He strikes fire in the hole and draws out his steel. Then they all move on again.

I’ve heard numerous interpretations of this passage over the years. Many of the interpretations dwell on the metaphorical power of the epilogue—it’s the final gnostic clue in the Judge’s web of mysteries; it’s the Promethean redemption of humanity against the Judge’s evil; it’s the spirit of civilization that will measure and conquer the bloody West, a progressive new dawn; it’s Cormac McCarthy’s signature, his designation of himself as the writer who carries the fire.

I’m fine with all of these interpretations, for I foolishly take Judge Holden at his word when he points out that, “Your heart’s desire is to be told some mystery. The mystery is that there is no mystery.” Let me eschew the symbolic then, at least momentarily, for the literal.

The epilogue’s literal imagery suggests a man working with post hole diggers: Is he building a fence? Constructing telegraph poles? Exploring? Surveying? Whatever his intentions, he marks and measures the land.

Whether the digger is a leader or not, he has followers, “the wanderers in search of bones” as well as “those who do not search.” Bones of what? Are the searchers hunting relics? (To revert to the metaphorical—sorry—are these bones the dead eyes Emerson warned us not to look through?). Or are the bones something else—dinosaur bones, Texas tea, carbon, fuel?

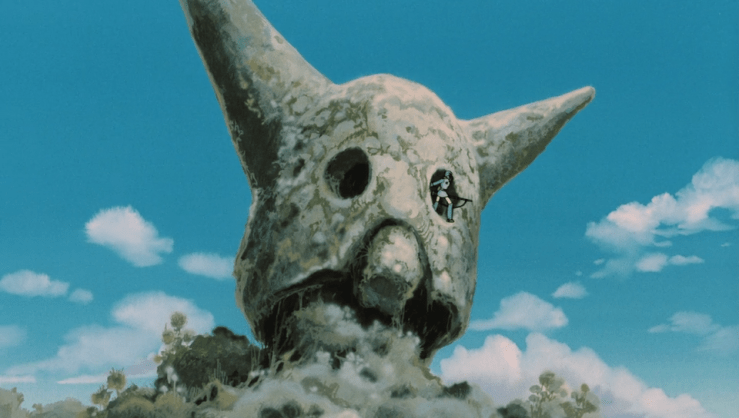

So There Will Blood and there will be bones: Daniel Day-Lewis’s Daniel Plainview, a misanthropic, near-malevolent, and ultimately murderous oil man—what I want to say is that he is (a failed version of) McCarthy’s Epilogue Digger. Is not There Will Be Blood a film about digging, about holes, falling in holes, dying in holes, striking fire from holes? And is not There Will Be Blood also a film about the abjection of holes—the oil, the mud, the muck, the blood that coats hands and faces, eyes, lips, ears burst? Of the recapitulation of the hole as the primal space for culture—a fertile, generative, fecund, deadly space? The hole as the space of shame and possibility? Daniel Plainview, surveying California, marking lines for his followers to follow, striking oil, striking fire. No?

We might see in Paul Thomas Anderson’s film a repetitious revision of McCarthy’s novel—a recasting of sorts, with Plainview possessed by Glanton’s maniacal spirit—and Glanton in turn possessed by the spirit of the Judge, the dark omnipresent bad father. Both film and novel mediate their Oedipal dramas in an utterly masculine world. Blood Meridian affords more speaking roles to women than There Will Be Blood does, but both see fit to discharge any notion of a mother from the Oedipal contests they depict, rendering the kid in each narrative the warden of strange gangs, strange wanderers. Anderson allows H.W. to suffer but live and perhaps thrive, to find a mate, to escape into new and alien territory, outside of the holes his surrogate father has dug. Our would-be hero of Blood Meridian, the kid, dies in an outhouse, an abject hole.

And Daniel Plainview—he murders the false priest (which the judge failed to do—although Tobin was a true priest though ex-priest), murders a version of himself—another brother, another Abel. He’s not a good guy. If we read McCarthy’s epilogue through his latest novel, The Road, or even through some of the lines in No Country for Old Men, we can see that “the good guys” are charged with carrying the fire—and is this not what the Epilogue Digger is doing? Carrying the fire, freeing the fire from the earth? Plainview would like to carry the fire, to generate new life, new communities, but he fails, he falls, he crumbles. He abandons his child, and then denies his child. “I’m finished!”

Am I finished? I’m now more confused than when I started this riff. The germ of the idea woke with me this morning—the alien landscape of PTA’s film seemed to restage for me moments in McCarthy’s novel in some waking dream—and like a dream seemed perfectly illogically logical. But bound up in my language I’m not so sure. What I did detect in the film, last night, that I had previously perhaps missed, or maybe forgotten, was how admirable Daniel Plainview often is, especially early on in the film—decisive, bold, asserting his own agency and working with his own hands, he’s a Nietzschean figure. But his paranoia gives way to madness and corruption. Okay. I’m finished.