“Uncle Sam Carrington”

by

Leonora Carrington

When Uncle Sam Carrington saw the full moon he was never able to stop laughing. A sunset had the same effect on Aunt Edgeworth. These two events created much suffering for my mother who took pleasure in a certain social prestige.

At the age of eight I was considered the most serious person in the family. My mother confided in me. She said that it was shameful that nobody would invite her out, that Lady Cholmendley-Bottame did not say Good Afternoon to her in the street. I was deeply upset.

Uncle Sam Carrington and Aunt Edgeworth lived in the house. They occupied the first floor. Thus, nothing could be done to hide this lamentable state of affairs. During the daytime I asked myself how I could free the family of this shame. Finally, it was impossible for me to bear the tension and my mother’s tears, things that made me suffer greatly. I decided to search for the solution. One afternoon when the sun had become very red and Aunt Edgeworth rejoiced in an especially repugnant manner, I took a jar of sweets, a loaf of bread and took to the road. In order to frighten the bats, I sang “O come into the garden, Maude, and hear the blackbirds sing!” (O, van al jardín, Maude, y escucha el canto de los miñes!)

My father sang this song when he wasn’t going to church, and another that began so: “It cost me seven shillings and sixpence.” (Esto me costo siete chelines y seis peniques.) I sang both songs with the same emotion.

“Good—” I thought, the trip has begun. Night certainly will bring me a solution. If I count the trees up to the place where I am going, I will not lose my way. Upon returning I will remember the number of trees.” But I forgot that I only knew how to count up to ten, and even then I made mistakes. So, in a little while I counted up to 10 several times until I became completely lost. Trees surrounded me everywhere.

“I am in the forest,” I said to myself. I was right.

The full moon diffused its clarity among the trees which permitted me to see some meters in front of me and the reason for a disquieting noise. Two cabbages that were fighting terribly made the disturbance. They tore off each other’s leaves with such ferocity that soon there were only a few sad leaves everywhere, and nothing of the cabbages.

“It doesn’t matter,” I said to myself. “It’s nothing more than a nightmare.” But suddenly I remembered that that night I had not gone to bed and, therefore, I could not treat it as a nightmare.

“It’s horrible,” I thought.

After that, I picked up the cadavers and continued my walk. In a little while, I came across a friend: the horse that, years later, would play an important part in my life.

“Hello!” he said to me. “Are you looking for something?” I explained to him the object of my excursion at such an advanced hour in the evening.

“Evidently,” he said, “from the social point of view it’s most complicated. Around here live two ladies who are occupied with similar questions. Your pursued goal consists in the eradication of your family shame. They are two very wise ladies. If you want, I will take you to them.”

The Señoritas Cunningham-Jones had a house surrounded discretely by uncultivated weeds and moss of another era. They were found in the garden about to play a game of checkers. The horse stuck out his head between the legs of some 1890 knickers and directed the word to the señoritas Cunningham-Jones.

“Let your little friend enter,” said the señorita who was seated at the right in a very distinct accent. “We are always ready to help in the matter of respectability.”

The other señorita bent her head benevolently. She was wearing a huge hat adorned with all kinds of horticultural specimens.

“Your family, señorita,” she said to me, offering me a Louis XV style chair, “does it continue the line of our beloved and lamented Duke of Wellington or that of Sir Walter Scott, that noble aristocrat of fine literature?”

I was a bit confused. There were no aristocrats in my family.

Taking notice of my fright, she said to me with the most enchanting smile: “Dear girl, you must realize that here we only arrange matters of the oldest and most noble families of England.”

A sudden inspiration illuminated my face. “In the dining room, at home…” I said.

The horse gave me a strong kick in the backseat.

“Don’t ever speak of anything so vulgar as food,” he said to me in a low voice.

Luckily, the señoritas were a little deaf. Correcting myself, I continued, perplexed. ln the living room there is a table upon which, it is said, a duchess left her glasses in 1700.”

“In that case,” the señorita answered, “Perhaps we can come to an agreement, but naturally, señorita, we will see ourselves obliged to ask for a somewhat steep reward.”

We easily understood each other. The señoritas got up saying: “Wait here some minutes; we will give you what you need. Meanwhile you can look at the illustrations in this book. It’s instructive and interesting. No library is complete without this volume. My sister and I always have lived by that admirable example.”

The book was titled: The Secrets of the Flowers of Distinction and the Coarseness of Food. When the two women had left, the horse asked: “Do you know how to walk without making a sound?”

“Certainly,” I answered.

“Then let’s see the señoritas devoted to their work,” he said. “But if your life matters to you, don’t make a sound.”

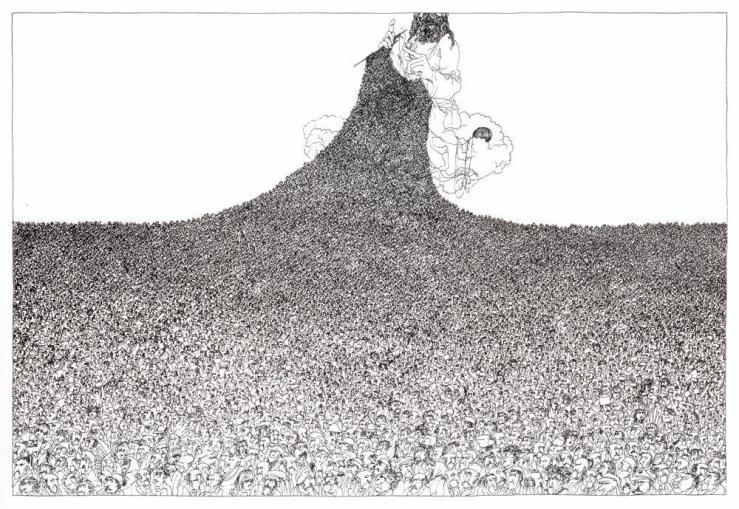

The señoritas were in their orchard which extended behind the house, surrounded by a wide wall. I mounted the horse and a surprising scene offered itself to my eyes: the señoritas Cunningham-Jones, each armed with an immense whip, were striking the vegetables, and shouting: “It’s necessary to suffer in order to go to heaven. Those who do not wear corsets will never arrive.”

The vegetables, on their part, fought among themselves, and the older ones threw the smaller ones at the señoritas with angry screams.

“Each time it happens so,” murmured the horse. “They are the vegetables that suffer on behalf of humanity. Soon you will see how they pick one for you, one that will die for the cause.”

The vegetables did not have an enthusiastic air over dying an honorable death. But the señoritas were stronger. Soon two carrots and a little cabbage fell between their hands.

“Quickly!” exclaimed the horse. “Back.”

Scarcely had we again sat down in front of THE COARSENESS OF FOOD, when the señoritas entered with the exact appearance as before. They gave me a little package that contained the vegetables, and in exchange for this I paid them with the jar of sweets and the little fritters.