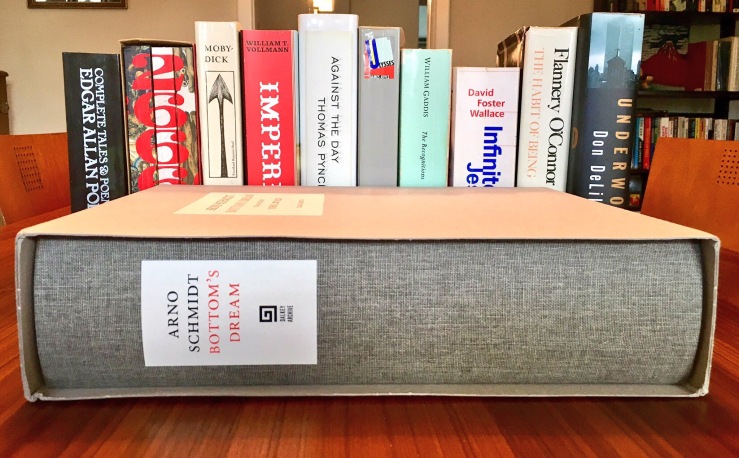

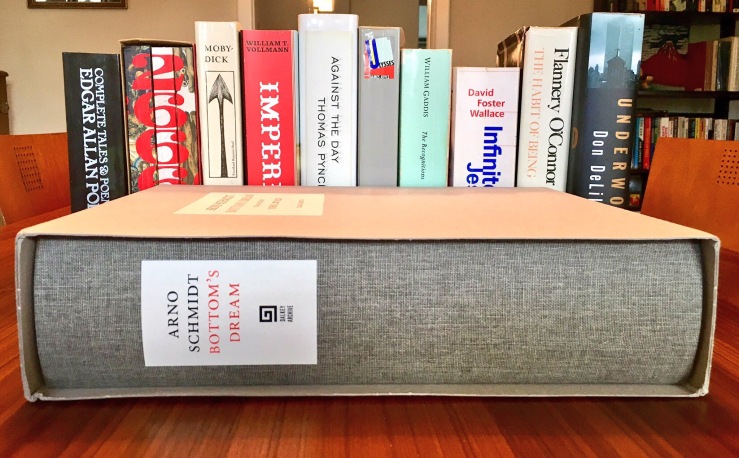

Arno Schmidt’s 1970 novel Bottom’s Dream is finally available in English translation by John E. Woods. The book has been published by the Dalkey Archive.

It is enormous.

As you can see in the picture above: Enormous.

But what’s Bottom’s Dream about? (This is the wrong question).

Dalkey’s blurb:

“I have had a dream past the wit of man to say what dream it was,” says Bottom. “I have had a dream, and I wrote a Big Book about it,” Arno Schmidt might have said. Schmidt’s rare vision is a journey into many literary worlds. First and foremost it is about Edgar Allan Poe, or perhaps it is language itself that plays that lead role; and it is certainly about sex in its many Freudian disguises, but about love as well, whether fragile and unfulfilled or crude and wedded. As befits a dream upon a heath populated by elemental spirits, the shapes and figures are protean, its protagonists suddenly transformed into trees, horses, and demigods. In a single day, from one midsummer dawn to a fiery second, Dan and Franzisca, Wilma and Paul explore the labyrinths of literary creation and of their own dreams and desires.

And Wikipedia’s summary:

The novel begins around 4 AM on Midsummer’s Day 1968 in the Lüneburg Heath in northeastern Lower Saxony in northern Germany, and concludes twenty-five hours later. It follows the lives of 54-year-old Daniel Pagenstecher, visiting translators Paul Jacobi and his wife Wilma, and their 16-year-old daughter Franziska. The story is concerned with the problems of translating Edgar Allan Poe into German and with exploring the themes he conveys, especially regarding sexuality.

Did I mention that it’s enormous?

Look, I know that dwelling on a book’s size probably has nothing to do with literary criticism, but Bottom’s Dream poses something of a special case. As an article on Bottom’s Dream at The Wall Street Journal points out, Schmidt’s opus is 1,496 pages long, contains over 1.3 million words, and weighs 13 pounds.

It’s a physical challenge as well as a mental challenge.

And, Oh that mental challenge!

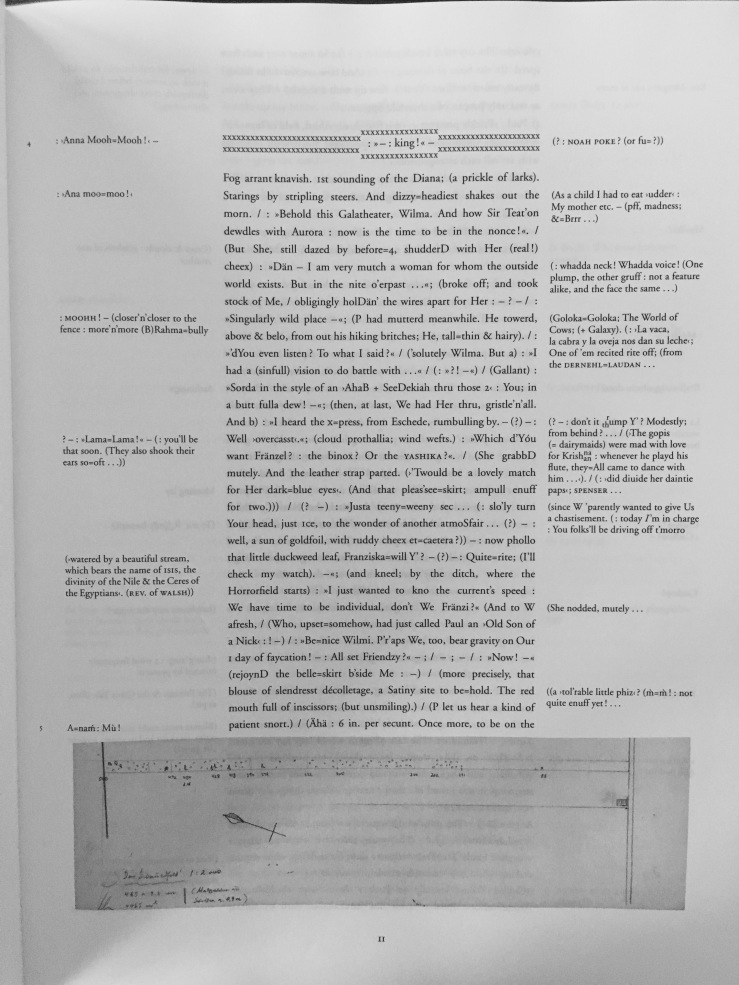

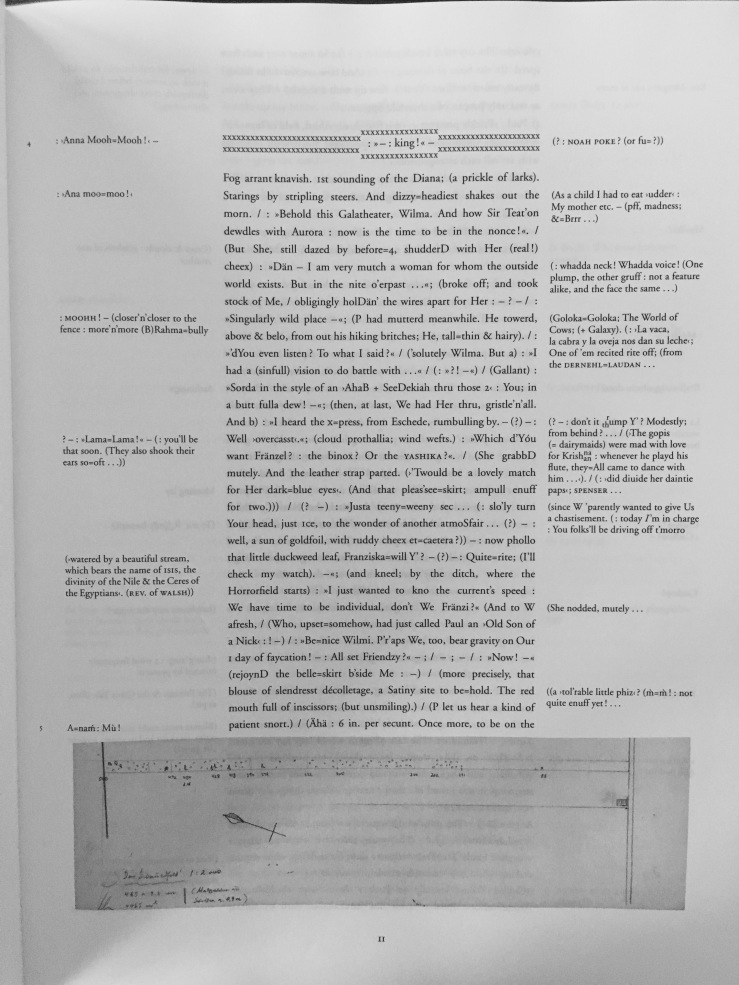

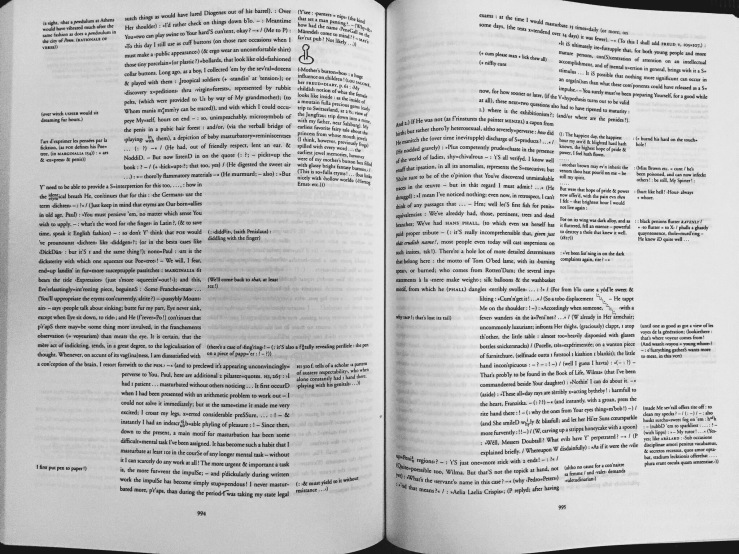

Here’s the first page of Bottom’s Dream (the pic links to a much larger image):

Hmmm…? What do you think?

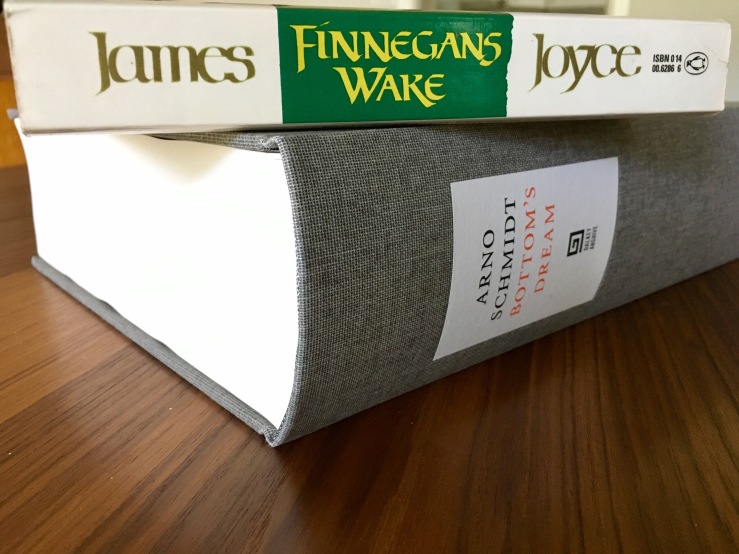

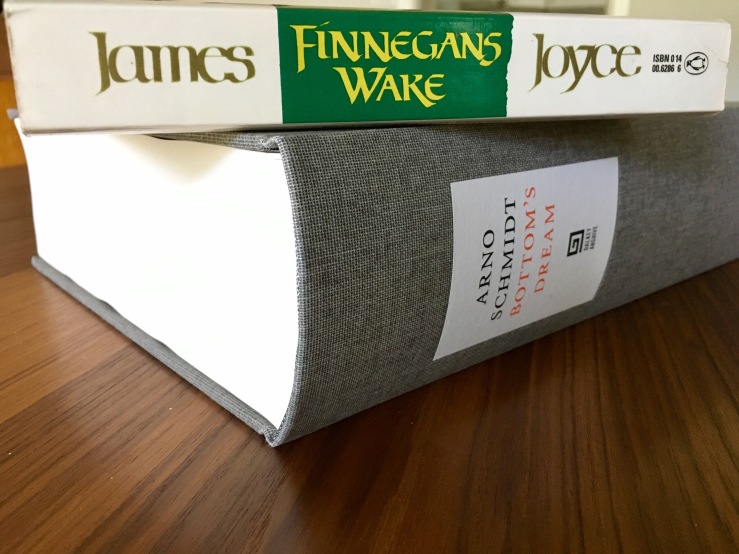

The obvious easy reference point here is Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which indeed Schmidt was actively following, both in form and style: competing columns, a fragmentary and elusive/allusive style, collage-like metacommentary, an etymological explosion—words as paint, text as meaning. Etc.

(Did I mention it’s a lot longer than Finnegans Wake? Did I mention it’s enormous?)

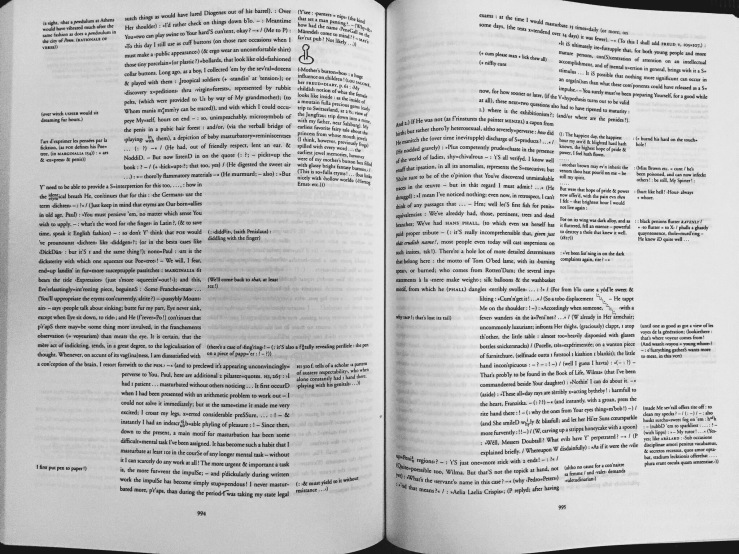

Here’s a glimpse at two random pages (don’t be afraid to click on that image and get the full, y’know, effect):

I’ll never forget one of my graduate school professors warning us not to “peer too long into Finnegans Wake.” He called it an abyss. (The man loved Joyce’s work, by the way, and had studied under Hugh Kenner. I’m not sure if he meant abyss pejoratively. It was, like I say, a warning).

Bottom’s Dream seems like an abyss. As its title (a reference to A Midsummer Night’s Dream) suggests, “it hath no bottom.”

After nine days, I’m “on” page 21 of Schmidt’s novel now, and I have no idea what’s going on. And not just because it’s a primal gobbledygook wordmass. No, part of my incomprehension results from a very strong physical reaction to “reading” Bottom’s Dream. This physical reaction goes beyond the size of the volume—although there’s certainly something to the size. I more or less have to read the thing on my dining room table; it’s dreadfully uncomfortable on a couch, and probably impossible on my hammock or in the bathtub. I can’t really hold it while I read it. I think this matters, although I can’t really say how right now. The multiple columns, marginalia, images, etc. are engaging but also fragment my attention—and I generally find myself flicking through Bottom’s Dream, rather than sustaining the will to follow the “plot.” Right now, anyway, I find myself wrapped up in the aesthetics of reading Bottom’s Dream. It’s a tactile read. I enjoy it most when I smooth my hands over it, jump out of the stream, 20, 30, 100 pages forward, backwards. Relax a little.

Otherwise, Bottom’s Dream becomes a bit of a nightmare for me: I get all dizzy, thirsty, my eyes seem to thrum. Something going on in the inner-ear. It’s like a slow-motion panic attack. When that abyss-stress comes on, I jump ahead.

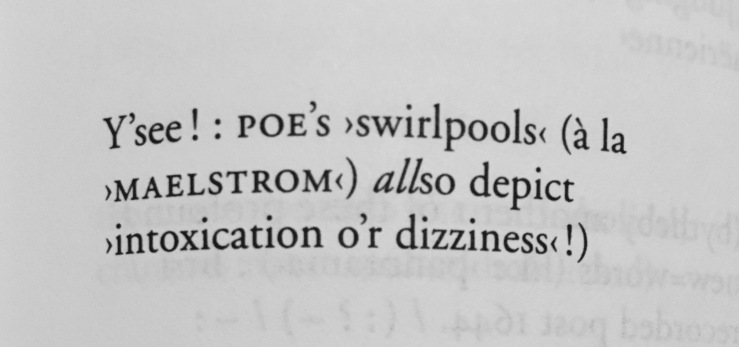

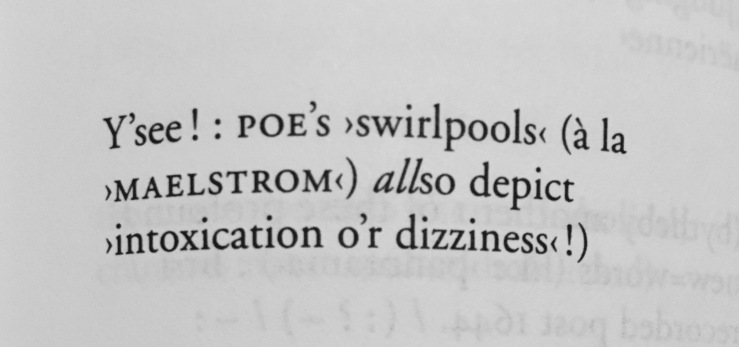

Which is how I found this bit of marginalia (I wish I’d recorded the page when I photographed it; but, also: the iPhone camera is a better recorder of Bottom’s Dream’s aesthetic textuality than any word-processing program. Even a scanner might straighten some of its bends and arcs, its voluminous volume):

Yes! Poe’s >swirlpools<! >intoxication o’r dizziness<! — there’s a description for me of my own reaction to reading Bottom’s Dream.

Poe might be something of a guide for me if I do try to stick out wandering through Bottom’s Dream, and his story “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” referenced above, seems a particularly nice parallel to Schmidt’s bigass book.

“Descent” relates the tale of a sailor (a voyager!–a, like, metaphorical reader, y’know) transformed by his encounter with the “Moskoestrom” —a swirling abyss from which no one returns. This vortex, “absurd and unintelligible,” breaks the sailor, “body and soul.” He can’t comprehend the storm. It’s unknowable, un-nameable. At best, he is able to make a sidelong glance at it, but can never plumb its depths. And not only is his glance broken, but all of his senses are fragmented. He escapes the maelstrom, but is unrecognizable to the sailors who rescue him. He becomes the voice of the vortex, the metonymy of a force he can perceive but can’t comprehend.

The maelstrom—the vortex, the abyss—this, for Poe, was language.

I’m not sure how deep I’ll travel into Schmidt’s maelstrom. I managed large sections of Finnegans Wake—but I had a guide in Joseph Campbell’s Skeleton Key. Someone to map out the terrain, show me the ropes, etc.

Obviously, there isn’t much English-language scholarship on Bottom’s Dream right now (and in a very real and radical sense that I’m not touching on here, Woods’s translation is its own separate book). There are a few blogs taking on Schmidt’s monster though. The Untranslated has been writing (in English) about the original German text for over a year now. At Messenger’s Booker, Tony Messenger has been writing about Woods’s translation. There might be some other folks out there attempting the same—if you know let me know. For now, my updates from this maelstrom will be sporadic at best.