As always: I’m sure it was my fault, and not the book’s fault, that I abandoned it.

(Except when it was the book’s fault).

And also: “Abandoned” doesn’t necessarily mean that I won’t come back to some of these books. (One of them even ended up on a list I made earlier this year of the books I’ve started the most times without ever finishing (and I finished one of those books this year, by the way)).

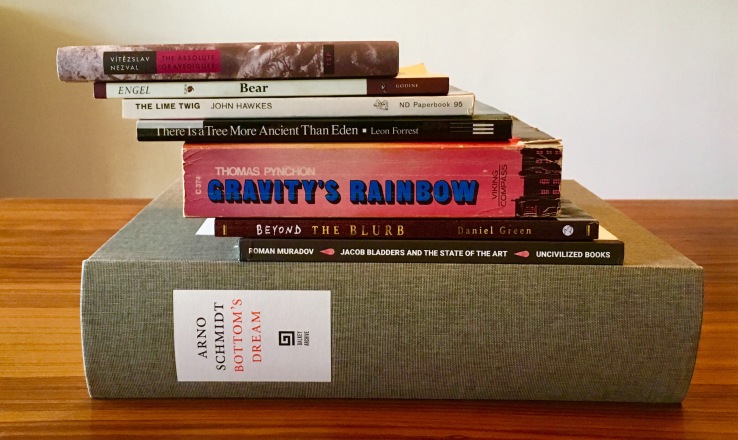

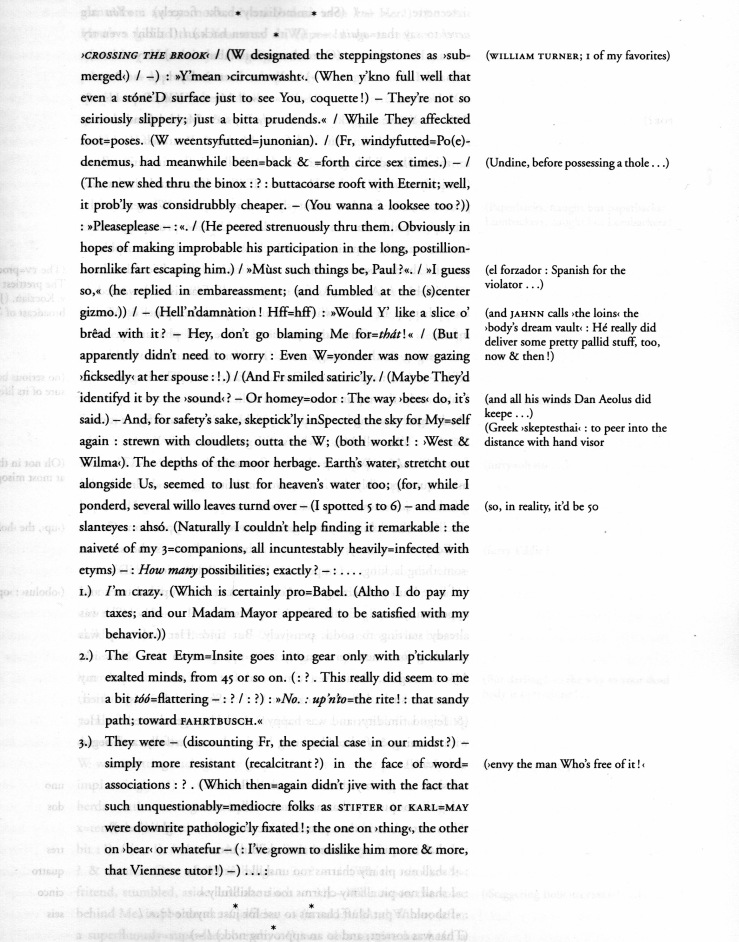

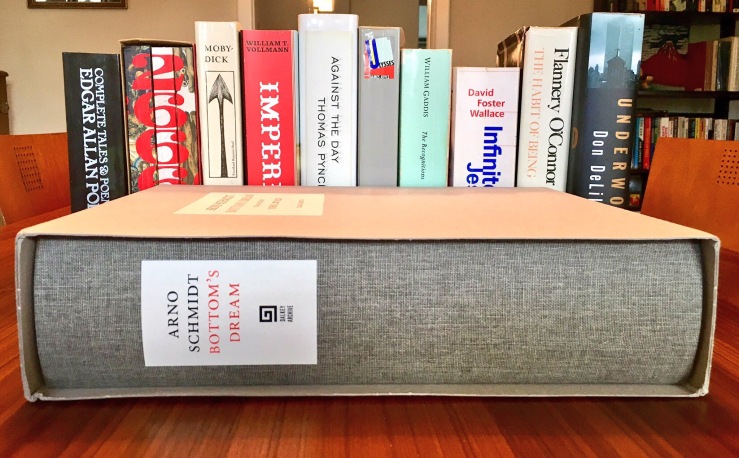

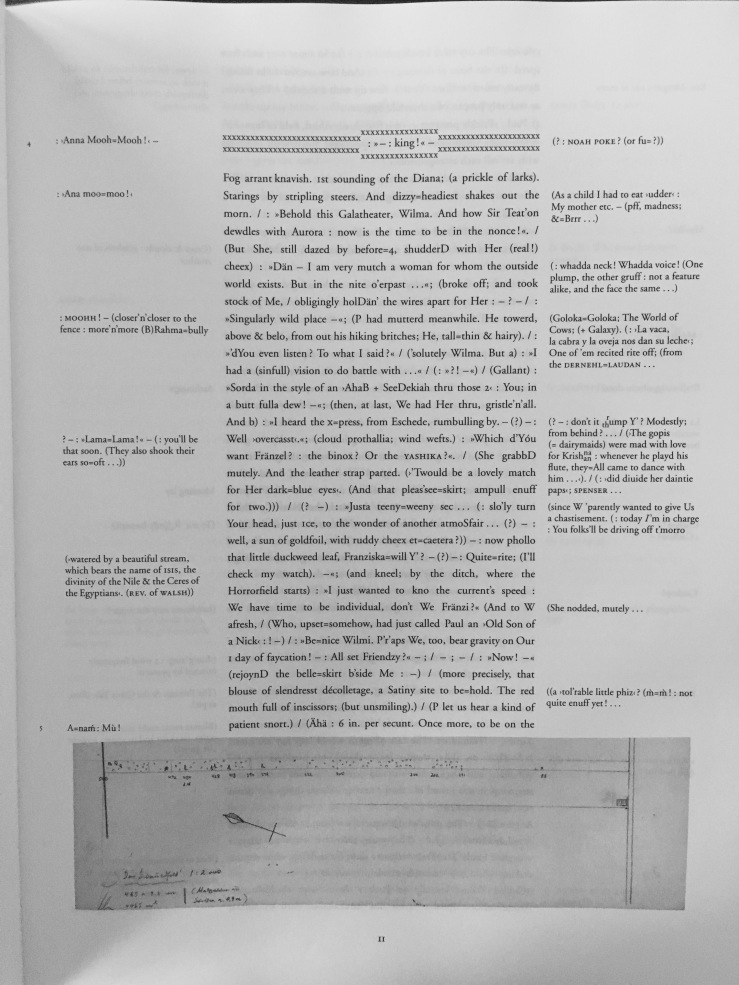

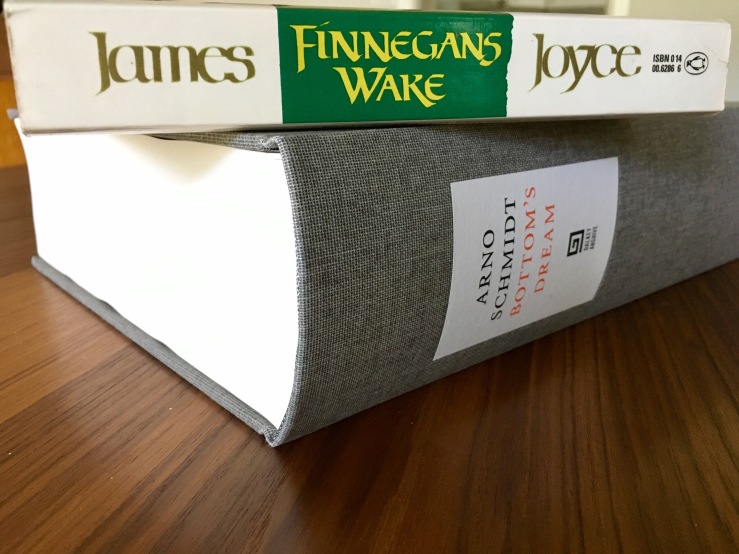

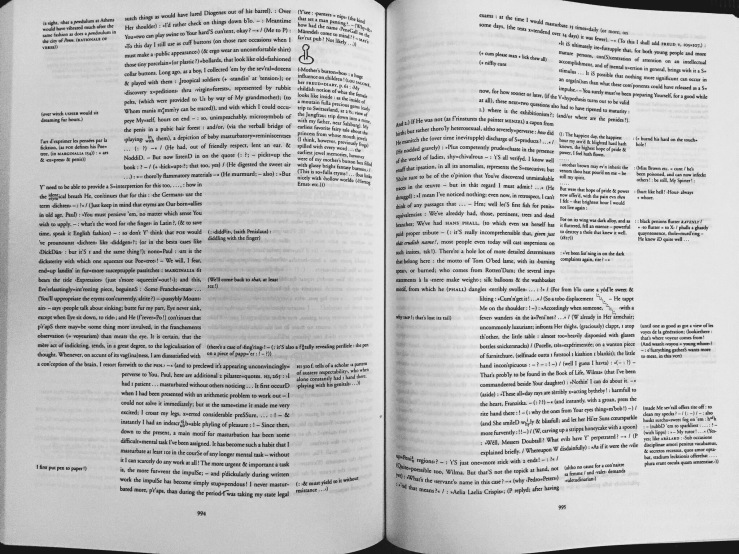

That big guy down on the bottom there, Arno Schmidt’s Bottom’s Dream (Eng. trans. by John Woods)?—I didn’t so much abandon it as I was told to put it away before we served Thanksgiving dinner at our house. There really isn’t a place for me to read the damn thing besides the dining room table. I’m sure I’ll dip into it more and I’m pretty sure I’ll never finish it in this lifetime. But I haven’t abandoned it forever. Earlier this year I wrote about the anxiety Bottom’s Dream produces in me.

Louis Armand’s The Combinations had the misfortune to show up as I was in the middle of a third reading of Gravity’s Rainbow. I read the first two chapters of Armand’s 888 page opus, then some other stuff showed up at the house in the mail, and then The Combinations got pushed to the back of the reading stack. The novel still interests me, but I’m not sure if I have the stamina right now.

Most of my reading experiences have as much to do with the time and the place that I read the book as they do with the form and content of the book. This year was not the time or the place for me to read Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, a strange book I really, really, really wanted to love, but abandoned maybe 35 pages in.

I actually read a large portion of Peter Biskind’s history of the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. I broke down and finally bought it this summer after multiple viewings of William Friedkin’s film Sorcerer and two trips through Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate. Biskind’s style is insufferable—gossipy and tawdry—and he swings wildly from venerating the book’s heroes (Bogdanovich, Coppola, Nichols, Scorsese, Malick, De Palma) to tearing them down (um, yeah, they were assholes). But there is an index which is of some use (although in reading Easy Riders, Raging Bulls you’re more likely to find out about a director’s drug problems or sex problems or money problems than you are to find out about, like, filmmaking). The worst part of Biskind’s book though is its repetitive insistence that not only did the Baby Boomers save Hollywood filmmaking, but also that the Boomers’ films were the last real outsider art ever to come out of Hollywood. Yeesh.

The first several stories in James Purdy’s short story collection 63: Dream Palace made me feel very, very sad, so I shelved it.

I read the first 258 pages of Samuel Delany’s novel Dhalgren. The book is 801 pages long and I couldn’t see it improving any. The book might be as great as everyone says it is, but it was mostly a boring mess (pages and pages of a character moving furniture around). On page 258, a character declares “There’s no reason why all art should appeal to all people.” I took that as a sign to ditch.

End with two limes: I’ve tried reading Thomas Bernhard’s The Limeworks too many times. I tried twice this year (once in the summer when it was simply too hot to read Thomas Bernhard). I read Bernhard’s Woodcutters though, and it is amazing.

And: I was reading John Hawkes’s The Lime Twig on Election Day, 2016 and haven’t been able to pick it up since then.