I read a lot of great books this year but had a hard time writing full reviews for all of them. These are some of the ones I liked the most.

Woodcutters, Thomas Bernhard

I finished Woodcutters just the other night, reading most of it in three sittings. (Actually, I was lying down. And it was very late at night, each time. I couldn’t pick the book up during daylight hours). Anyway, I finished Bernhard’s novel just the other night, so maybe I’ll muster something on it, but for now: I think this may be my favorite Bernhard novel so far! I can only think of a handful of writers so masterful at mimicking the operations of consciousness, of replicating consciousness (and conscience) reflecting on consciousness. (I even had to stop and do a too-hasty read of Ibsen’s play The Wild Duck, a plot point of Woodcutters). What happens in Woodcutters? A man sits in a chair remembering things. It’s fucking amazing.

White Mythology is comprised of two novellas, Skinner Boxed and Love’s Alchemy. The first and longer novella, Skinner Boxed, takes place over a few days in the life of a psychiatrist; it’s a zany zagging yarn, crowded with MacGuffins and red herrings (a missing wife, a bastard son, a new anti-depressant drug, etc.). Oh, and it’s a Christmas story! Did I mention that? (Skinner Boxed takes its epigram from A Christmas Carol…and another from Gravity’s Rainbow). Love’s Alchemy is a kind of time-arrangement, or locale-arrangement—a story in pieces that the reader has to assemble. I enjoyed White Mythology (especially Skinner Boxed, which, typing this out, I realize I’d like to read again).

The Dick Gibson Show, Stanley Elkin

The Franchiser, Stanley Elkin

Somehow I’d made it to 2016 without reading Elkin. I read these two back-to-back. The best parts of The Dick Gibson show are as good as anything any of those other big postmodern dudes have written. (Okay. If not as good, nearly as good). I didn’t review The Dick Gibson Show because Elkin basically did it for me in his Paris Review interview. The Franchiser is a comic tragedy—or do I mean tragic comedy? It does all that inversion stuff: high-low/low-high. A novel of things and colors, both mythic and predictive, The Franchiser feels simultaneously ahead of its time and yet still very much bound to the 1970s, when it was first published.

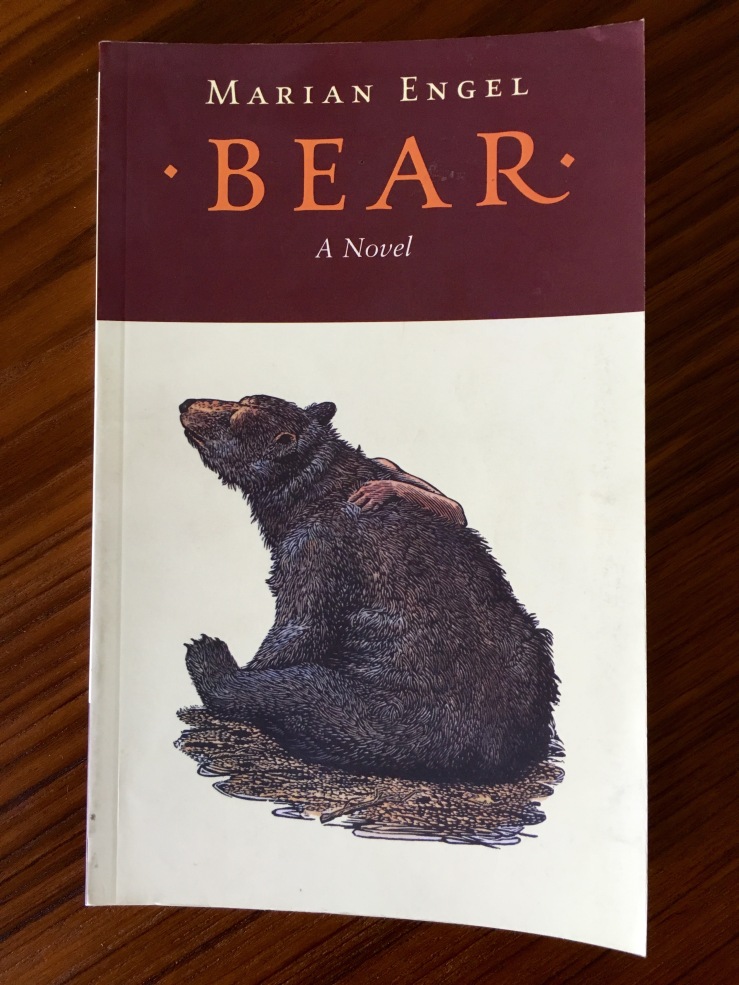

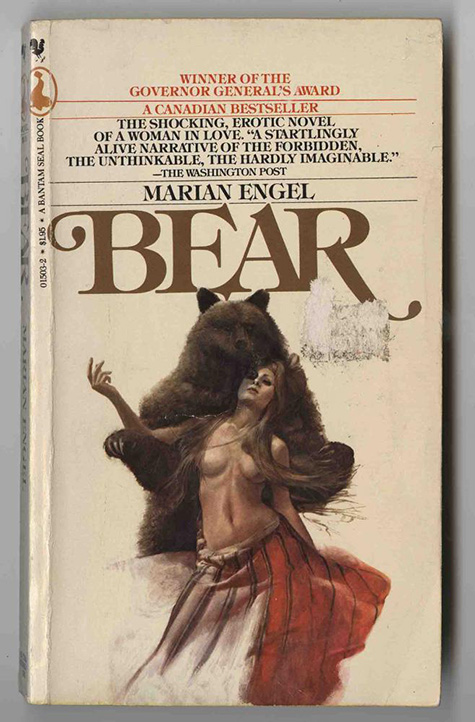

Bear, Marian Engel

This slim novel is somehow simultaneously lucid and surreal, conventional and bizarre, romantic and ironic, heady and dry. And wet. A bibliographer travels to a remote island in Ontario to index an old library. I’m going to read this one again.

(Oh, the bibliographer has a sexual relationship with a bear. Like, a real bear. Not a metaphorical bear. A real one).

Collected Stories, William Faulkner

I didn’t read them all because I’m not a greedy pig. I read a lot of them though. Lord.

There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden, Leon Forrest

I will read Leon Forrest’s There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden again in the first quarter of 2017 and I will write a proper Thing on it. I read it in a two-day blur, drinking up the sentences greedily, perhaps not (no, strike that perhaps) comprehending the plot so much as sucking up a feeling, a place, a mood, a vibe. But there’s so much history reverberating behind the novel’s lens. Like I said (wrote): I need to read it again, which will kinda sorta be like reading it for the first time. Which is a thing one might say of any great novel.

The Weight of Things, Marianne Fritz

I read this really early in the year and I only remember the impression of reading it—not the plot itself, but the language—I remember horror, cruelty, pain. And this is why I need to write about the books I read.

The Inheritors, William Golding

A colleague told me to read Golding’s account of telepathic Neanderthals and their eventual encounter with predatory Homo sapiens. I’ll admit that I’d unfairly written off Golding as YA stuff, but the evocation of a prelingual (and postlingual) consciousness is fascinating here. It’s also a ripping quest narrative starring the Holy Fool Lok, who laughs in terror and joy. What stands out most in my memory, beyond the premise, is Golding’s concrete prose. I’m glad my colleague told me to read The Inheritors.

The Transmigration of Bodies, Yuri Herrera

I read Herrera’s The Transmigration of Bodies in a blurry weekend (sensing a pattern here) and enjoyed it very much: Grimy neon noir poured into mythological contours. Lovely.

The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa

This was the best novel I read in 2016 that I’d never read before. So good that I reread it immediately (the only two books I can recall doing that with in recent memory areBlood Meridian and Gravity’s Rainbow). It was even better the second time. The Leopard is the story of Prince Fabrizio of Sicily who witnesses — and takes part in — the end of the old order era during the Italian reunification. Fiery and lascivious but also intellectual and stoic, Fabrizio the Leopard is the most engrossing character I read this year. Di Lampedusa’s novel takes us through his mind, through his age—places he himself isn’t fully cognizant of at times. I can’t recommend this novel enough: History, religion, death, sex. Sense and psyche, pleasure and loss, crammed with rich, dripping set pieces: dances and dinners and games of pleasure (light sadomasochism!) in summer estates. But its plots and poisons and pieces are not the main reason for The Leopard—read it for the language, the sentences, the sumptuous words. Its final devastating images are still soaked and sunken into my addled brains.

The Absolute Gravedigger, Vítězslav Nezval

I wedged these poems into the end of my third proper trip through Gravity’s Rainbow; I was also dipping into Rilke’s Duino Elegies and the Rider-Waite tarot. It’s all crammed together in a surreal web in my memory: shimmering horror, broken badlands, entropy and degradation—but life.

Cow Country, Adrian Jones Pearson

Cow Country (not pictured above because I listened to the audiobook) is a bizarre, disjointed satire of community colleges in particular and educational administration in general. (And: a satire on our slavish sensibilities of time ). It’s also a wonderful send-up of dialectical methodology—or rather the dialectical impulse to, like, resolve things. And by things, I mean Jones Pearson (or is it AJP? Or Adrian Ruggles Pearson? Or A.J. Perry? Or—nevermind)—Our Author (whoever) breaks down the way that all of our breakdowns breakdown under any real scrutiny.

Hilda and the Stone Forest, Luke Pearson

I read all of the Hilda books this year with my kids. And I read them by myself. And my kids read them by themselves. More than once. Hilda and the Stone Forest is the best one yet—richer, denser, funnier, and more devastating than anything Pearson’s done yet. The Stone Forest is stuffed with miniature epics and minor gags, and the central story of Hilda and her mother in the titular stone forest is somehow both bleak and heartwarming. Great stuff.

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon

I actually wrote a lot about Gravity’s Rainbow (probably a major reason I didn’t write more about other stuff)—but I still wish I’d written more. I will write more. I’ve been listening to the audiobook for my fourth trip through.

Marketa Lazarova, Vladislav Vančura

Strange, violent, funny, and ultimately devastating, this Marketa Lazarova is a medieval tale of family loyalty, kidnapping, and love. Nothing I can do here would be a substitute for Vančura’s vivid, surreal voice—a voice that guides the story cynically, ironically, but also energetically, buoyantly. One of the best things I read all year.