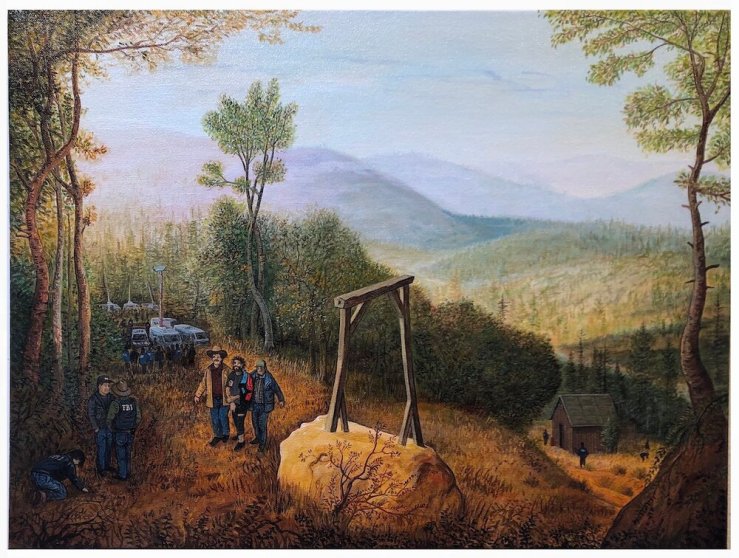

The Apprehension of Ted Kaczynski (Lincoln, Montana – April 3, 1996), 2019 by Sandow Birk (b. 1962)

The Apprehension of Ted Kaczynski (Lincoln, Montana – April 3, 1996), 2019 by Sandow Birk (b. 1962)

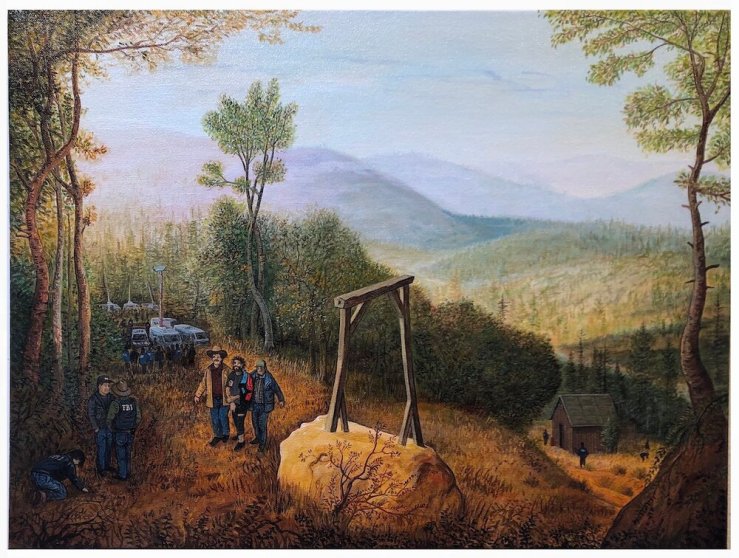

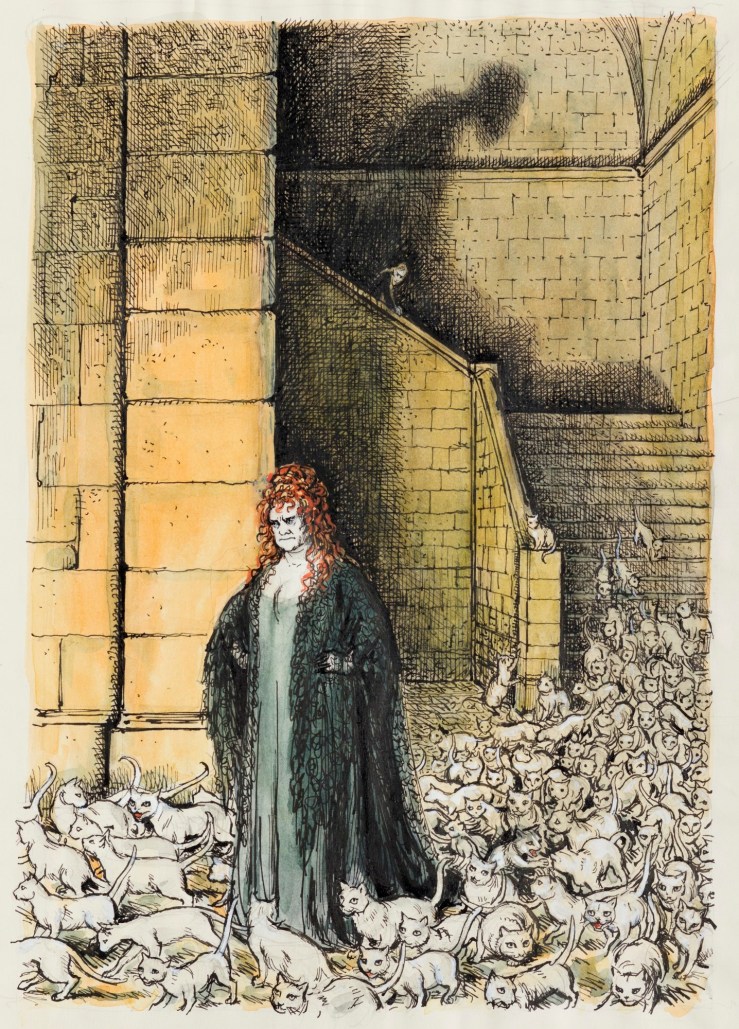

Do You Know My Aunt Eliza?, 1941 by Leonora Carrington (1917–2011)

I shall never forget the observation of one of our crew as we were passing slowly by the entrance of the bay in our way to Nukuheva. As we stood gazing over the side at the verdant headlands, Ned, pointing with his hand in the direction of the treacherous valley, exclaimed, ‘There—there’s Typee. Oh, the bloody cannibals, what a meal they’d make of us if we were to take it into our heads to land! but they say they don’t like sailor’s flesh, it’s too salt. I say, maty, how should you like to be shoved ashore there, eh?’ I little thought, as I shuddered at the question, that in the space of a few weeks I should actually be a captive in that self-same valley.

The French, although they had gone through the ceremony of hoisting their colours for a few hours at all the principal places of the group, had not as yet visited the bay of Typee, anticipating a fierce resistance on the part of the savages there, which for the present at least they wished to avoid. Perhaps they were not a little influenced in the adoption of this unusual policy from a recollection of the warlike reception given by the Typees to the forces of Captain Porter, about the year 1814, when that brave and accomplished officer endeavoured to subjugate the clan merely to gratify the mortal hatred of his allies the Nukuhevas and Happars.

On that occasion I have been told that a considerable detachment of sailors and marines from the frigate Essex, accompanied by at least two thousand warriors of Happar and Nukuheva, landed in boats and canoes at the head of the bay, and after penetrating a little distance into the valley, met with the stoutest resistance from its inmates. Valiantly, although with much loss, the Typees disputed every inch of ground, and after some hard fighting obliged their assailants to retreat and abandon their design of conquest.

The invaders, on their march back to the sea, consoled themselves for their repulse by setting fire to every house and temple in their route; and a long line of smoking ruins defaced the once-smiling bosom of the valley, and proclaimed to its pagan inhabitants the spirit that reigned in the breasts of Christian soldiers. Who can wonder at the deadly hatred of the Typees to all foreigners after such unprovoked atrocities?

Thus it is that they whom we denominate ‘savages’ are made to deserve the title. When the inhabitants of some sequestered island first descry the ‘big canoe’ of the European rolling through the blue waters towards their shores, they rush down to the beach in crowds, and with open arms stand ready to embrace the strangers. Fatal embrace! They fold to their bosom the vipers whose sting is destined to poison all their joys; and the instinctive feeling of love within their breast is soon converted into the bitterest hate.

The enormities perpetrated in the South Seas upon some of the inoffensive islanders will nigh pass belief. These things are seldom proclaimed at home; they happen at the very ends of the earth; they are done in a corner, and there are none to reveal them. But there is, nevertheless, many a petty trader that has navigated the Pacific whose course from island to island might be traced by a series of cold-blooded robberies, kidnappings, and murders, the iniquity of which might be considered almost sufficient to sink her guilty timbers to the bottom of the sea.

Sometimes vague accounts of such thing’s reach our firesides, and we coolly censure them as wrong, impolitic, needlessly severe, and dangerous to the crews of other vessels. How different is our tone when we read the highly-wrought description of the massacre of the crew of the Hobomak by the Feejees; how we sympathize for the unhappy victims, and with what horror do we regard the diabolical heathens, who, after all, have but avenged the unprovoked injuries which they have received. We breathe nothing but vengeance, and equip armed vessels to traverse thousands of miles of ocean in order to execute summary punishment upon the offenders. On arriving at their destination, they burn, slaughter, and destroy, according to the tenor of written instructions, and sailing away from the scene of devastation, call upon all Christendom to applaud their courage and their justice.

How often is the term ‘savages’ incorrectly applied! None really deserving of it were ever yet discovered by voyagers or by travellers. They have discovered heathens and barbarians whom by horrible cruelties they have exasperated into savages. It may be asserted without fear of contradictions that in all the cases of outrages committed by Polynesians, Europeans have at some time or other been the aggressors, and that the cruel and bloodthirsty disposition of some of the islanders is mainly to be ascribed to the influence of such examples.

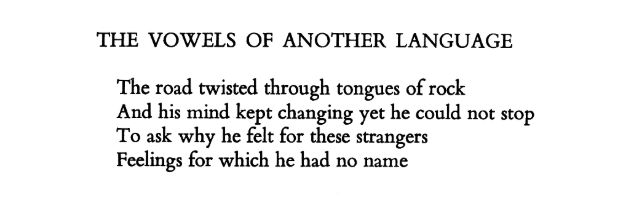

On the Way to the Doctor, 1974 by Charles W. Stewart (1915 – 2001).

Part of a series of unpublished illustrations that were to illustrate Mervyn Peake’s 1950 novel, Gormenghast. (More here.)

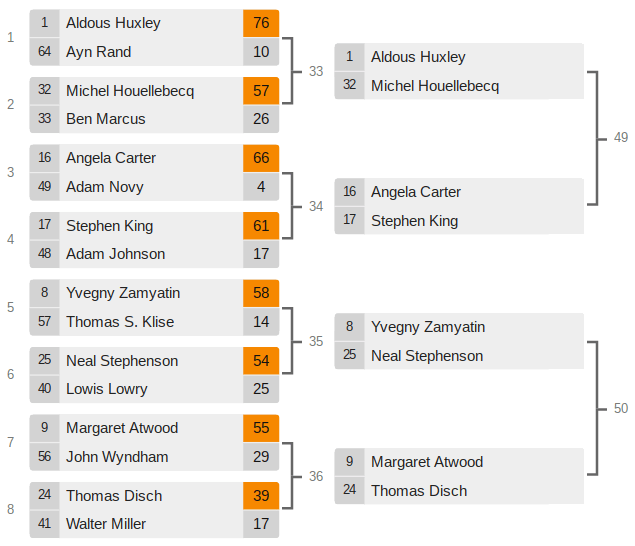

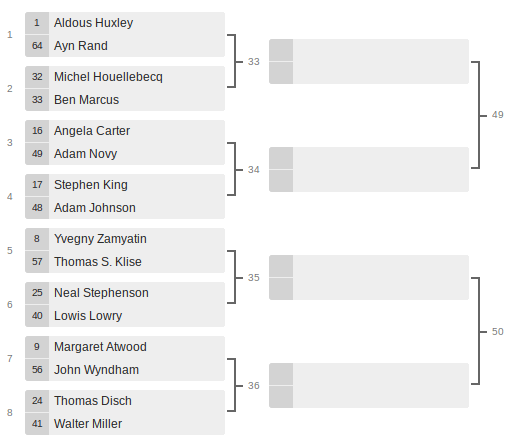

On Sunday, I came up with a list of 64 writers that have written novels or stories that either anticipate, reflect, or otherwise describe our zeitgeist. The first dozen or so seeds (as well as the bottom dozen or so) came rather intuitively to me, but the writers in the middle were seeded somewhat randomly. I used Twitter’s poll feature to determine the winners of Round One. In most of my polls, I included a third option, where voters could choose just to see the poll results instead of actually voting; I won’t be doing that going forward, because the data looks, if not exactly skewed, well, just a little off-putting, as in Round 1, Bracket 8 below:

My intuition is that Disch (Camp Concentration) and Walter Miller (A Canticle for Leibowitz) were either too obscure for many folks, or at least not writers very many people are passionate about.

Sinclair Lewis (It Can’t Happen Here) tied with China Miéville (Marxism, steampunk, Perdido Street Station, bold baldness) and went to a tie (I managed to misspell China Miéville’s name in both tweets)—

I was also surprised by top-ten seed Octavia Butler (Kindred, Parable of the Sower) losing to José Saramago (Blindness). I suppose I seeded Saramago too low.

Here are the results of Round One and the match-ups for Round Two:

Bracket 46 is particularly painful for me!

Poll results by tweet:

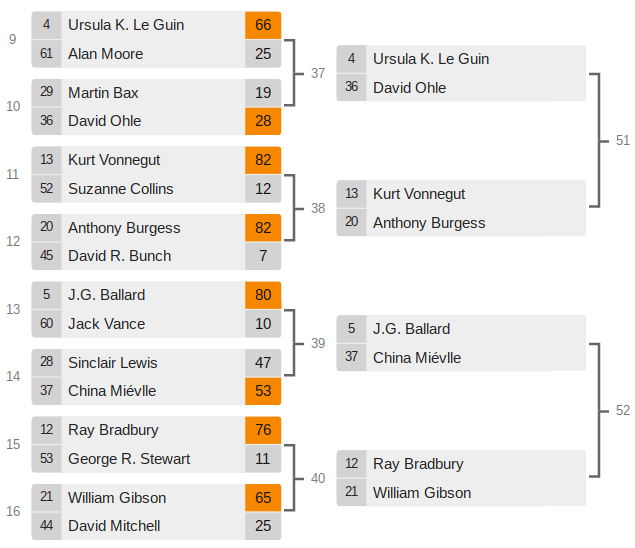

The Cutters, 2017 by Christopher Noulton (b. 1961)

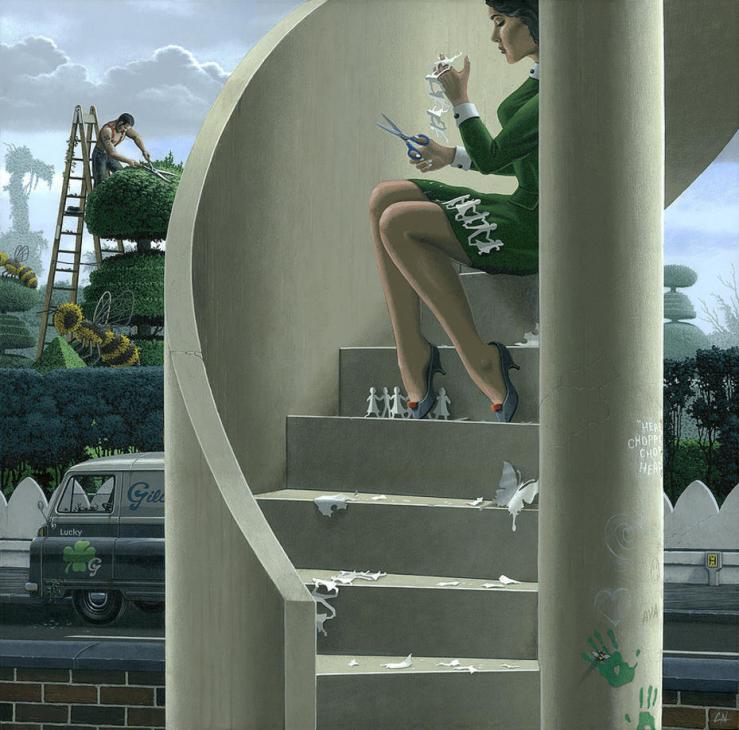

Interference, 2011 by Nigel Cooke (b. 1973)

Everything Bartleby says in Herman Melville’s “Bartleby”:

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to,” said he.

“What is wanted?”

“I would prefer not to,” he said, and gently disappeared behind the screen.

“I would prefer not to.”

“I prefer not to,” he replied in a flute-like tone.

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“I prefer not.”

“I prefer not to,” he respectfully and slowly said, and mildly disappeared.

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“At present I prefer to give no answer,” he said, and retired into his hermitage.

“At present I would prefer not to be a little reasonable,” was his mildly cadaverous reply.

“I would prefer to be left alone here,” said Bartleby, as if offended at being mobbed in his privacy.

Upon asking him why he did not write, he said that he had decided upon doing no more writing.

“No more.”

“Do you not see the reason for yourself,” he indifferently replied.

“I have given up copying,” he answered, and slid aside.

“I would prefer not,” he replied, with his back still towards me.

“Not yet; I am occupied.”

“I would prefer not to quit you,” he replied, gently emphasizing the not.

“Sitting upon the banister,” he mildly replied.

“No; I would prefer not to make any change.”

“There is too much confinement about that. No, I would not like a clerkship; but I am not particular.”

“I would prefer not to take a clerkship,” he rejoined, as if to settle that little item at once.

“I would not like it at all; though, as I said before, I am not particular.”

“No, I would prefer to be doing something else.”

“Not at all. It does not strike me that there is any thing definite about that. I like to be stationary. But I am not particular.”

“I know you,” he said, without looking round,—”and I want nothing to say to you.”

“I know where I am,” he replied, but would say nothing more, and so I left him.

Maybe you’re bored, maybe you’re stuck inside, missing NCAA March Madness, watching the world’s madness through a screen. Maybe this will be a diversion. (I’m hoping it’s a diversion for me.)

I came up with a list of 64 writers that have written novels or stories that either anticipate, reflect, or otherwise describe our zeitgeist. (I realize now that I’ve forgotten a bunch, but, hey.) After a certain point, there wasn’t much thought put into seeding the tournament.

I’ll be doing running polls on Twitter for the next few days, starting today, with brackets 1-4 launching today.

Here are the brackets for Round 1:

A couple of days ago I took my daughter to the bookstore for what I imagine will be the last time for a while. She browsed the “Teen” section, which is new for both of us, and picked out a few books.

I picked up The Complete Novels of Charles Wright, which collects The Messenger, The Wig, and Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About. I’m generally not a fan of omnibus editions, but I’m not sure how easy it is to get a hold of The Messenger or Absolutely Nothing (the bookstore had another copy of The Wig, which makes me think it’s in wider circulation). This Harper Perennial edition has no introduction, and I’m not crazy about the no-contrast cover, but it’s got a nice texture to it.

I also picked up Steve Erickson’s debut novel Days Between Stations, in part because Thomas Pynchon blurbed it (even though I wasn’t wild about the last novel I read because Pynchon blurbed it, Wurlitzer’s Nog), and also in part because I’m a sucker for Vintage Contemporaries editions, especially ones with covers illustrated by Rick Lovell.

Here’s Pynchon’s blurb:

Steve Erickson has that rare and luminous gift for reporting back from the nocturnal side of reality, along with an engagingly romantic attitude and the fierce imaginative energy of a born storyteller. It is good news when any of these qualities appear in a writer– to find them all together in a first novelist is reason to break out the champagne and hors-d’oeuvres.

Pynchon also blurbed Jim Dodge’s novel Stone Junction (or wrote an introduction for it rather), which I’ve been looking for unsuccessfully for a while now—not because Pynchon blurbed it (which I only found out recently), but because I’ve heard it compared to Charles Portis. I was unsuccessful again this time.

I hope I’ll be able to get out of the house soon, but in the meantime I have more than enough reading material.

“Herman Melville”

by

W.H. Auden

Towards the end he sailed into an extraordinary mildness,

And anchored in his home and reached his wife

And rode within the harbour of her hand,

And went each morning to an office

As though his occupation were another island.

Goodness existed: that was the new knowledge.

His terror had to blow itself quite out

To let him see it; but it was the gale had blown him

Past the Cape Horn of sensible success

Which cries: “This rock is Eden. Shipwreck here.”

But deafened him with thunder and confused with lightning:

–The maniac hero hunting like a jewel

The rare ambiguous monster that had maimed his sex,

The unexplained survivor breaking off the nightmare–

All that was intricate and false; the truth was simple.

Evil is unspectacular and always human,

And shares our bed and eats at our own table,

And we are introduced to Goodness every day,

Even in drawing-rooms among a crowd of faults;

He has a name like Billy and is almost perfect,

But wears a stammer like a decoration:

And every time they meet the same thing has to happen;

It is the Evil that is helpless like a lover

And has to pick a quarrel and succeeds,

And both are openly destroyed before our eyes.

For now he was awake and knew

No one is ever spared except in dreams;

But there was something else the nightmare had distorted–

Even the punishment was human and a form of love:

The howling storm had been his father’s presence

And all the time he had been carried on his father’s breast.

Who now had set him gently down and left him.

He stood upon the narrow balcony and listened:

And all the stars above him sang as in his childhood

“All, all is vanity,” but it was not the same;

For now the words descended like the calm of mountains–

–Nathaniel had been shy because his love was selfish–

Reborn, he cried in exultation and surrender

“The Godhead is broken like bread. We are the pieces.”

And sat down at his desk and wrote a story.

Wild Sunflowers, 2015 by Denis Sarazhin (b. 1982)

Who Are We Now?, 2017 by Gregory Ferrand (b. 1975)

D’Audieu, 2017 by Jonathan Leaman (b. 1954)

Troubadour, 1959 by Remedios Varo (1908-1963)