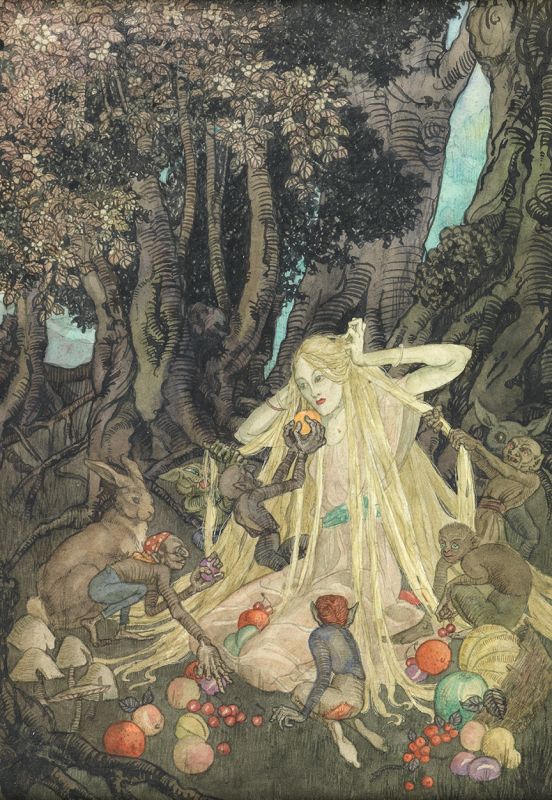

And Norma nodded and apologized and washed her blood-soaked knickers in secret so that her mother wouldn’t throw her out, so that she wouldn’t discover that her worst fear had come true, until finally one day Norma realized she’d been wrong all that time: the Sunday seven wasn’t the blood that stained her underwear but what happened to your body when that blood stopped flowing. Because one day, on her way home from school, Norma found a little paperback book with a ripped cover and Fairy Tales for Children of All Ages written across it, and on opening it at random the first thing she saw was a black-and-white illustration of a little hunchback crying terrified while a coven of witches with bat wings stabbed the hunch on his back, and the illustration was so strange that, ignoring the time and the ominous rain clouds, ignoring the dishes waiting to be washed and her siblings who needed feeding before their mother got home from the factory, Norma sat down at the bus stop to read the whole story, because at home there was never time to read anything, and even if there were she wouldn’t be to, with her siblings’ racket, the blare of the TV and her mother’s constant yelling, not to mention Pepe’s fooling around or the piles of homework that awaited her each night after washing the pots, which she herself had used at noon before leaving for school; and so she pulled the hood of her coat over her head and folded her legs under her skirt and she read the whole story from start to finish, the tale of the two hunchbacks, that’s what the fairy tale was called, and it was about a hunchback who lost his way one evening in the woods close to his home, dark and sinister woods where witches were said to meet to do their evil deeds, and that was why the little fellow was so frightened to find himself lost there, unable to find his way home, wandering blindly as night fell, until suddenly he spied a fire in the distance, and thinking it might be a campfire he ran towards it, convinced that he’d been saved. So imagine his surprise when he arrived at the clearing with the gigantic fire only to realize it was a Witches’ Sabbath: a coven of horrifying witches with bat wings and claws instead of hands, all dancing around the blazing fire in the most macabre fashion while they sang: Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three; Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three; Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three, and they were cackling their terrible witchy cackles and howling up at the full moon, and the hunchback, who, still unseen, had taken cover behind an enormous rock not far from the fire, listened to that cyclic chant and, unable to explain how, unable to explain the overwhelming urge that came over him, took a deep breath as the witches sang their next Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three, jumped onto the rock and shouted at the top of his lungs: Thursday and Friday and Saturday, six! His cry resounded with surprising force in that clearing, and on hearing him the witches froze where they were, petrified around the fire that was casting horrible shadows on their beastly faces. And seconds later they were all running around, hovering between the trees, shrieking and hollering that they had to find the human who’d said that, and the poor hunchback, once again crouched behind the rock, trembled at the thought of the fate awaiting him, but when at last the witches found him they didn’t hurt him as he’d imagined, nor did they turn him into a frog or a worm, or much less eat him. Instead, they took the man and cast spells to conjure enormous magical knives, which they used to cut off his hunch, all without spilling a drop of blood or hurting him at all, because the witches were pleased that the little fellow had improved their song, which, truth be told, they were beginning to find a little boring, and when the hunchback saw that he no longer had a hump, that his back was completely flat and that he didn’t have to walk hunched over, he was happy, enormously happy and contented, and as well as curing his hump the witches also gave him a pot of gold and thanked him for having improved their song, and before resuming their Witches’ Sabbath they showed him the way out of that enchanted part of the woods, and the little man ran all the way home and straight to his neighbor, who was also a hunchback, to show him his back and the riches he’d received from the witches, and his neighbor, who was a mean, jealous man, believed that he deserved those gifts more, because he was more important and more intelligent and those witches must be real fools to go around giving away gold just like that, and by the following Friday the jealous hunchback had convinced himself that he should copy his neighbor, and as night fell he entered the woods in search of that coven of cretinous hags and he walked for hours in the darkness until he, too, lost his way, and just as he was about to collapse against a tree and cry out in fear and desperation he glimpsed, in the distance, in the thickest, gloomiest part of the woods, a fire surrounded by witches dancing and singing: Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three; Thursday and Friday and Saturday, six; Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three; Thursday and Friday and Saturday, six, and with that the jealous neighbor scurried towards them and hid behind the same enormous rock, and at the next round of Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday, three; Thursday and Friday and Saturday, six, the vile little man – who, despite believing himself more intelligent than his neighbor, was not the smartest of fellows – opened his mouth, took the deepest breath he could, cupped his hands around his lips and shouted: SUNDAY SEVEN! with all his might. And when the witches heard him they froze on the spot, petrified in the middle of their dance, and that dimwit of a hunchback emerged from his hiding place and opened his arms to reveal himself, thinking they’d all flock to him to fix his hunchback and hand him a pot of gold even bigger than the one they’d given his neighbor, but instead he saw that the witches were furious, clawing at their chests and yanking out great clumps of flesh with their own nails, scratching their cheeks and pulling the flowing hair that crowned their horrific heads, roaring like wild beasts and screaming: Who’s the fool who said Sunday? Who’s the wretch who ruined our song? And then they caught sight of the mean little man and zoomed towards him, and with hexes and jinxes they conjured the hump they’d removed from the first man and put it on him, and as a punishment for his imprudence and greedthey placed it on his front, and instead of a pot of gold they pulled out a pot of warts that hopped out of the container and immediately stuck to the body of that despicable man, who was left with no choice but to return to the town like that, with two humps instead of one and warts all over his face and body, and all for having come out with his Sunday seven, the book explained – and in the final illustration of the story the jealous neighbor appeared with those two humps, one deforming his back and the other making him look pregnant, and that was the moment Norma finally understood how silly she’d been to think that the fateful Sunday seven was the blood that stained her knickers each month, because clearly what it referred to was what happened when that blood stopped flowing; what happened to her mother after a spell of going out at night in her flesh-colored tights and her high heels, when from one day to the next her belly would start to swell, reaching grotesque proportions before finally expelling a new child, a new sibling for Norma, a new mistake that generated a new set of problems for her mother, but, above all, for Norma: sleepless nights, crushing tiredness, reeking nappies, mountains of sicky clothes, and crying, unbroken, ceaseless crying. Yet…

From Fernanda Melchor’s novel Hurricane Season. English translation by Sophie Hughes. From New Directions (US) and Fitzcarraldo Editions (UK) .

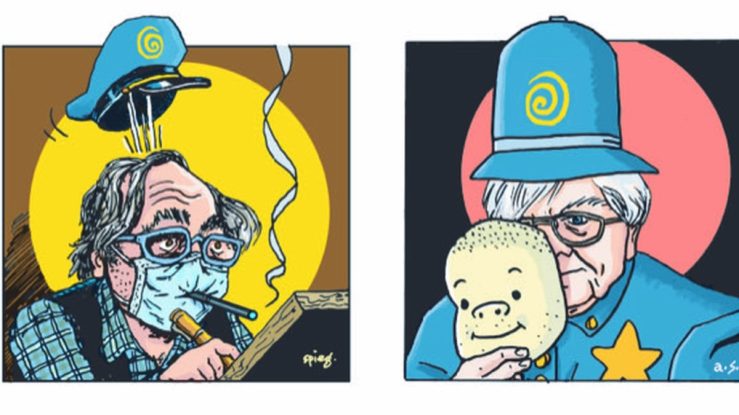

Small Beer Press had a warehouse sale last month, so I ordered two by the late avant-garde sci-fi writer Carol Emshwiller. I ordered Carmen Dog, which is what I take to be her most lauded novel, based on this blurb from Ursula Le Guin:

Small Beer Press had a warehouse sale last month, so I ordered two by the late avant-garde sci-fi writer Carol Emshwiller. I ordered Carmen Dog, which is what I take to be her most lauded novel, based on this blurb from Ursula Le Guin: