My sweetheart and I had sealed our commitment at high noon. My father had raised a cup to our good fortune, issued a stern proclamation against peddlers, bestowed happiness and property upon us and all our progeny, and the party had begun. Whole herds had been slaughtered for our tables. The vineyards of seven principalities had filled our casks. We had danced, sung, clung to one another, drunk, laughed, cheered, chanted the sun down. Bards had pilgrimaged from far and wide, come with their alien tongues to celebrate our union with pageants, prayers, and sacrifices. Not soon, they’d said, would this feast be forgotten. We’d exchanged epigrams and gallantries, whooped the old Queen through her death dance, toasted the fairies and offered them our firstborn. The Dwarfs had recited an ode in praise of clumsiness, though they’d forgotten some of the words and had got into a fight over which of them had dislodged the apple from Snow White’s throat, pushing each other into soup bowls and out of windows. They’d thrown cakes and pies at each other for awhile, then had spilled wine on everybody, played tug-of-war with the Queen’s carcass, regaled us with ribald mimes of regicide and witch-baiting, and finally had climaxed it all by buggering each other in a circle around Snow White, while singing their gold-digging song. Snow White had kissed them all fondly after-wards, helped them up with their breeches, brushed the crumbs from their beards, and I’d wondered then about my own mother, who was she?—and where was Snow White’s father? Whose party was this? Why was I so sober? Suddenly I’d found myself, minutes before midnight, troubled by many things: the true meaning of my bride’s name, her taste for luxury and collapse, the compulsions that had led me to the mountain, the birdshit on the glass coffin when I’d found her. Who were all these people, and why did things happen as though they were necessary? Oh, I’d reveled and worshipped with the rest of the party right to the twelfth stroke, but I couldn’t help thinking: we’ve been too rash, we’re being overtaken by something terrible, and who’s to help us now the old Queen’s dead?

Author: Biblioklept

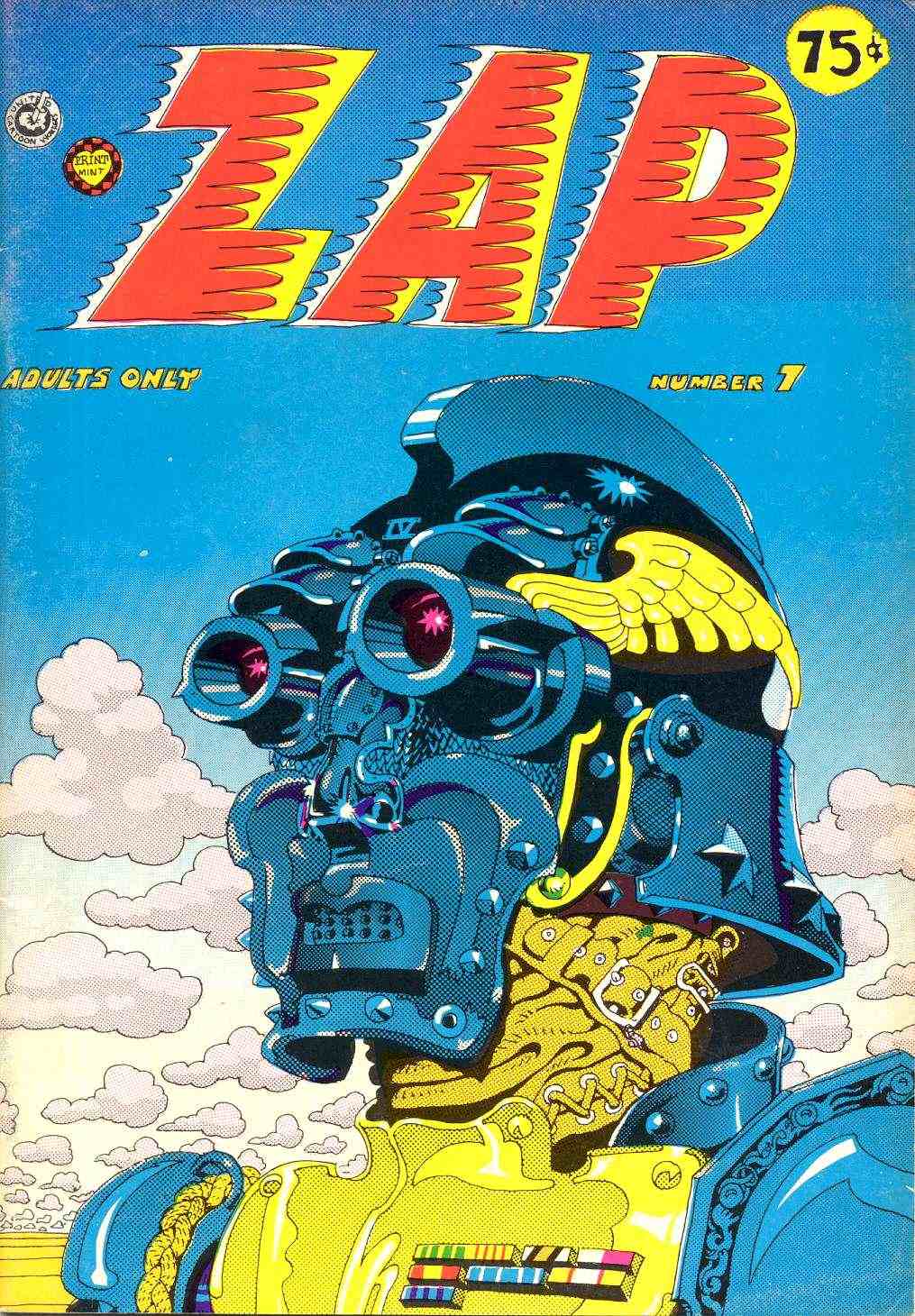

Sunday Comix

Cover art for ZAP Comix #7 by Spain Rodriguez, 1973

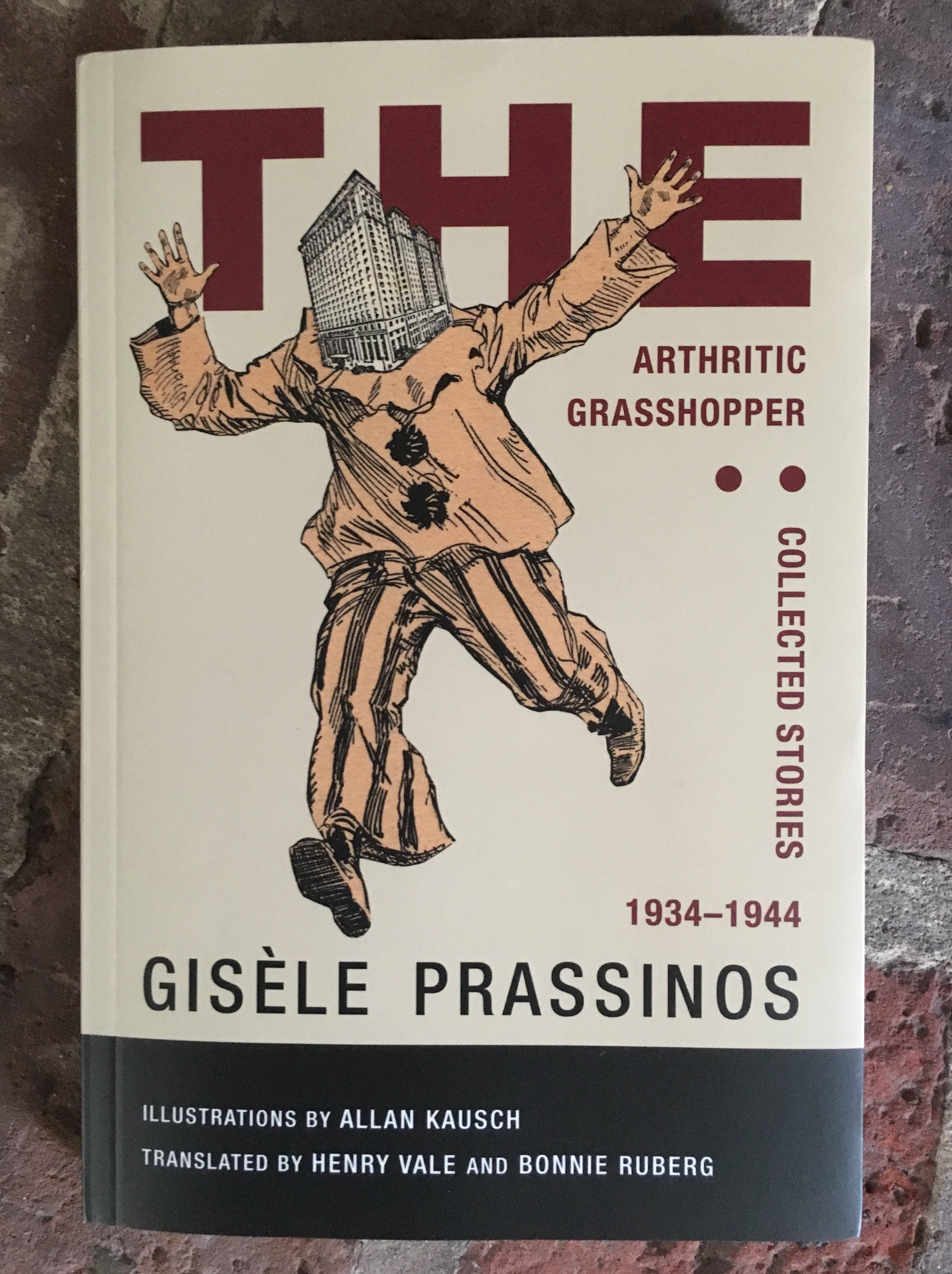

A review of Gisèle Prassinos’s collection of surreal anti-fables, The Arthritic Grasshopper

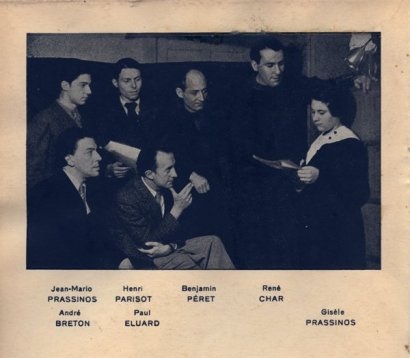

I can’t remember which particular Surrealist I was googling when I learned about Gisèle Prassinos. I do know that it was just a few weeks ago, and I’ve had an interest in Surrealist art and literature since I was a kid, so I was a bit stunned that I’d never heard of her before now—strange, given the origin of her first publication. In 1934, when she was 14, Prassinos was “discovered” by André Breton, and the Surrealists delighted in what they called her “automatic writing.” (Prassinos would later reject that label, and go as far as to declare that she had never been a surrealist). Her first book, La Sauterelle arthritique (The Arthritic Grasshopper) was published just a year later.

I somehow found a .pdf of one of her stories, “A Nice Family,” a bizarre little tale that runs on its own surreal mythology. The story struck me as simultaneously grandiose and miniature, dense but also skeletal. It was impossible. Surreal. I wanted more.

Luckily, just this spring Wakefield Press released The Arthritic Grasshopper: Collected Stories, 1934-1944, a new English translation of a 1976 compendium of Prassinos’s tales, Trouver sans checher. The translation is by Henry Vale and Bonnie Ruberg, whose introduction to the volume is a better review and overview than I can muster here. Ruberg offers a miniature biography, and shares details from her letters and visits with Prassinos. She situates Prassinos within the Surrealists’ gender biases: “For a young writer such as Prassinos, being involved with the surrealists would have meant gaining access to resources like publishers, but it also would have meant being fetishized and marginalized.” Ruberg characterizes Prassinos’s tales eloquently and accurately—no simple feat given the material’s utter strangeness:

Taken collectively, their effect is a piercing cackle, a complete disorientation, rather than an ethical lesson. The politics of these stories are absurdist. They upend the world by making children dangerous, by reanimating the dead, by letting the carefully tended domestic deform, foam, and melt. No social structure holds power in the world of these stories—not on the basis of gender, or nationality, or class. The force that reigns is chaos.

Let’s look at that reigning chaos.

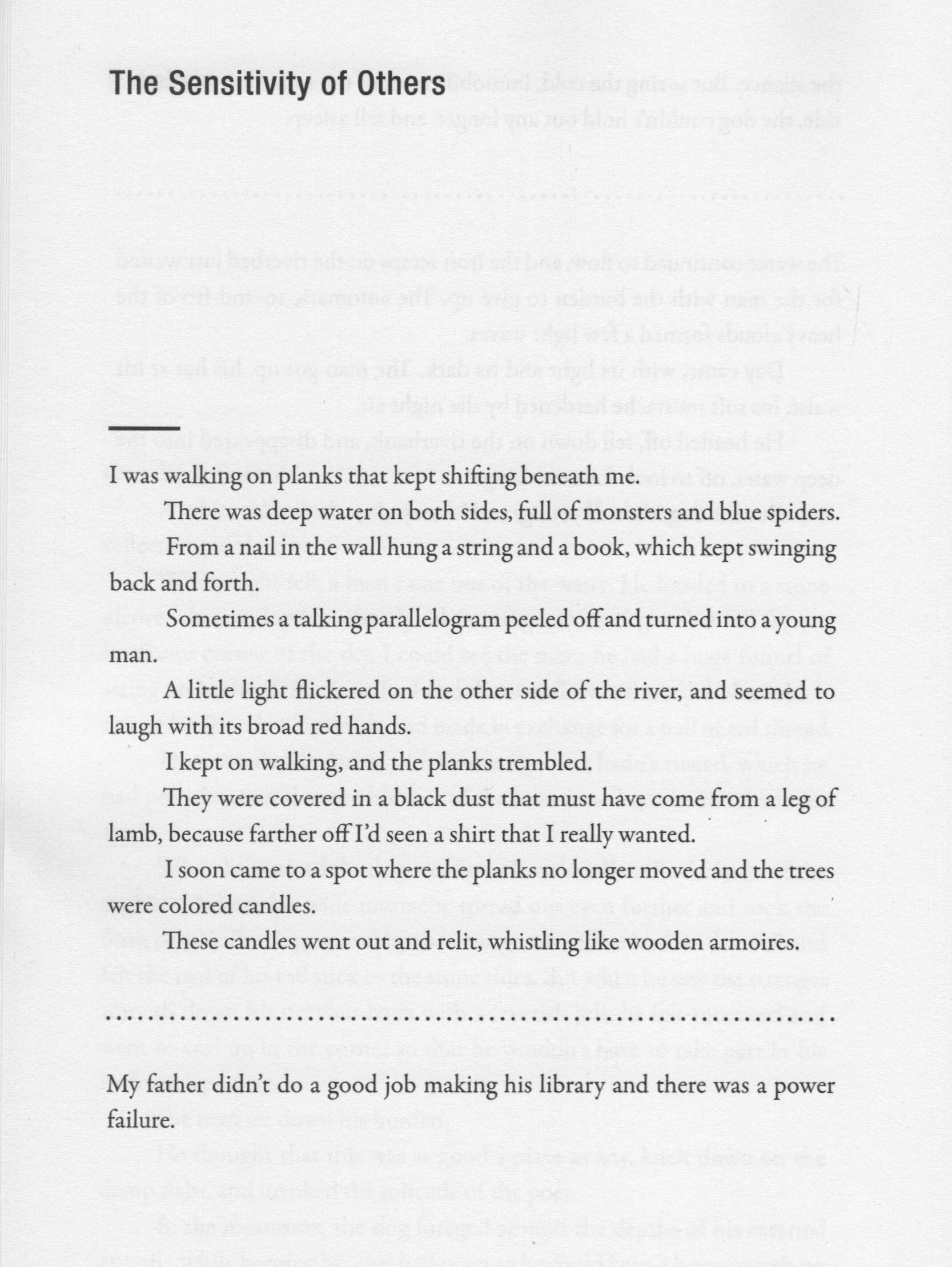

In “The Sensitivity of Others,” one of the earliest tales in the volume, we get the sparest narrative action seemingly possible: A speaker walks forward. And yet dream-nightmare touches impinge on all sides and on all senses. The opening line shows a world that is never stable, and if monsters and other dangers lurk just on the margins of our narrator’s shifting path, so do wonders and the promise of strange knowledge. Here’s the tale in full:

I still have no idea what to make of the punchline there at the end, but those final images—a father, a faulty library, a power failure—hang heavy against the narrator’s trembling walk.

Many of Prassinos’s anti-fables conclude with such apparent non sequiturs, and yet the final lines can also cast a weird light back over the previous sentences. In “Photogenic Quality,” a dream-tale about the act of writing itself, the final line at first appears as sheer absurdity. A man receives a pencil from a child, whittles it into powder, blots the powder on paper, and throws the paper in the river (more things happen, too). The tale concludes with the man declaring, “Brass is made from copper and tin.” It’s possible to enjoy the absurdity here on its own; however, I think we can also read the last line as a kind of Abracadabra!, magic words that describe an almost alchemical synthesis—a synthesis much like the absurd modes of transformative writing that “Photogenic Quality” outlines.

You’ll see above one of Allan Kausch’s illustrations for The Arthritic Grasshopper. Kausch’s collages pointedly recall Max Ernst’s surreal 1934 graphic novel Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness). Kausch’s work walks a weird line between horror and whimsy; images from old children’s books and magazines become chimerical figures, sometimes cute, sometimes horrific, and sometimes both. They’re lovely.

Surreal figures shift throughout the book—monks and kings, daughters and mothers, deep sea divers and knights and salesmen and talking horses—all slightly out of place, or, rather, all making new places. Even when Prassinos establishes a traditional space we might think we recognize—often a fairy trope—she warps its contours, shaping it into something else. “A Marriage Proposal,” with its unsuspecting title, opens with “Once upon a time” — but we are soon dwelling in impossibility: “the garter snake appeared in the doorway, arm in arm with the snail, who was slobbering with happiness.” Other stories, like “Tragic Fanaticism,” immediately condense fairy tales into pure images, leaving the reader to suss out connections. Here is that story’s opening line: “A black hole, a little old woman, animals.” At five pages, “Tragic Fanaticism” is one of the collection’s longer stories. It ends with a four line poem, sung by five red cats to the old woman: “Go home and burn / Darling / You’re the only one we’ll love / Trash Bin.”

I still have a number of stories to read in The Arthritic Grasshopper. I’ve enjoyed its tales most when taken as intermezzos between sterner (or compulsory) reading. There’s something refreshing in Prassinos’s illogic. In longer stretches, I find that I tire, get lazy—Prassinos’s imagery shifts quickly—there’s something even picaresque to the stories—and keeping up with its veering rhythms for tale after tale can be taxing. Better not to gobble it all up at once. In this sense, The Arthritic Grasshopper reminds me strongly of another recently-published volume of surreal, imagistic stories that I’ve been slowly consuming this year: The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. In their finest moments, both of these writers can offer new ways of looking at art, at narrative, at the world itself.

I described Prassinos’s tales as “anti-fables” above—a description that I think is accurate enough, as literary descriptions go—but that doesn’t mean there isn’t something that we can learn from them (although, to be very clear, I do not think literature has to offer us anything to learn). What Prassinos’s anti-fables do best is open up strange impossible spaces—there’s a kind of radical, amorphous openness here, one that might be neatly expressed in the original title to this newly-translated volume—Trouver sans checher—To Find without Seeking.

In her preface (titled “To Find without Seeking”) Prassinos begins with the question, “To find what?” Here is a question that many of us have been taught we must direct to all the literature we read—to interrogate it so that it yields moral instruction. Prassinos answers: “The spot where innocence rejoices, trembling as it first meets fear. The spot where innocence unleashes its ferocity and its monsters.” She goes on to describe a “true and complete world” where the “earth and water have no borders and each us can live there if we choose, in just the same way, without changing our names.” Her preface concludes by repeating “To find what?”, and then answering the question in the most perfectly (im)possible way: “In the end, the mind that doesn’t know what it knows: the free astonishing voice that speaks, faceless, in the night.” Prassinos’s anti-fables offer ways of reading a mind that doesn’t know what it knows, of singing along with the free faceless astonishing voice. Highly recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept originally ran this review in August of 2017.]

Birthday — Dorothea Tanning

Birthday, 1942 by Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012)

A review of Taking Care, Joy Williams’ debut short story collection

Let’s begin with a paragraph from Joy Williams’ story “Winter Chemistry.” Let’s begin with this paragraph because I think it makes a better argument for reading Joy Williams’ story “Winter Chemistry” than I ever could. Here’s the paragraph:

Judy Cushman and Julep Lee had become friends the summer before when they were on the beach. It was a bitter, shining Maine day and they were alone except for two people drowning just beyond the breaker line. The two girls sat on the beach, eating potato chips, unable to decide if the people were drowning or if they were just having a good time. Even after they disappeared, the girls could not believe they had really done it. They went home and the next day read about it in the newspapers. From that day on, they spent all their time together, even though they never mentioned the incident again.

The paragraph is a perfect little short story on its own, the second part of its second sentence deployed in a simple, casually devastating manner (“they were alone except for two people drowning just beyond the breaker line”). There’s a wonderful ambiguity to the whole passage, an ambiguity most resonant in the second “they” of the fourth sentence—what is the referent of that “they”? The drowned victims? Or the girls who witnessed the drowning, inert, snacking?

Stripes of ambiguity like this one run throughout the sixteen stories in Joy Williams’ 1982 debut collection Taking Care. Williams’ characters—often young girls or young women—cannot quite fit what they immediately perceive into a coherent schema of the phenomenological world.

In the opening story, “The Lover,” for instance, Williams portrays a woman dissociating, told in a present-tense, free indirect style that trips into our hero’s troubled mind:

The girl wants to be in love. Her face is thin with the thinness of a failed lover. It is so difficult! Love is concentration, she feels, but she can remember nothing. She tries to recollect two things a day. In the morning with her coffee, she tries to remember and in the evening, with her first bourbon and water, she tries to remember as well. She has been trying to remember the birth of her child now for several days. Nothing returns to her. Life is so intrusive! Everyone was talking. There was too much conversation! … The girl wished that they would stop talking. She wished that they would turn the radio on instead and be still. The baby inside her was hard and glossy as an ear of corn. She wanted to say something witty or charming so that they would know she was fine and would stop talking. While she was thinking of something perfectly balanced and amusing to say, the baby was born.

There are over a dozen exclamation marks in “The Lover,” deployed in artful disregard for the conventional creative writing advice that eschews using those pointed poles. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a story use exclamation marks so effectively: “There was too much conversation!” Williams evokes her character’s emerging anxiety as it tips close to mania. We never discover a cause for her dissociation and neither does she. We get only the fallout, the effects, sentences piling together without a clear destination other than dissociation. She tries to find some kind of an answer, calling up an AM radio show called Action Line to talk to the Answer Man:

The girl goes to the telephone and dials hurriedly. It is very late. She whispers, not wanting to wake the child. There is static and humming. “I can’t make you out,” the Answer Man shouts. “Are you a phronemophobiac?” The girl says more firmly, “I want to know my hour.” “Your hour came, dear,” he says. “It went when you were sleeping. It came and saw you dreaming and it went back to where it was.”

A later story in Taking Care, “The Excursion,” returns to the themes of dissociation we saw in “The Lover.” In “The Excursion,” a girl named Jenny is unstuck in time. Her consciousness reels between childhood and adulthood; memories of her parents compound with adult experiences with her lover in Mexico. The result is startling, disorienting, and often upsetting. (And again, Williams deploys her exclamation marks like artful verbal pricks).

“The Lover” and “The Excursion” are probably the two most formally-daring stories in Taking Care, but their ambiguous spirit is part and parcel of the collection as a whole. Consider “Shorelines,” a rare first-person perspective story, which begins with the narrator trying to set order where there is none:

I want to explain. There are only the two of us, the child and me. I sleep alone. Jace is gone. My hair is wavy, my posture good. I drink a little. Food bores me. It takes so long to eat. Being honest, I must say I drink. I drink, perhaps, more than moderately, but that is why there is so much milk. I have a terrible thirst. Rum and Coke. Grocery wine. Anything that cools. Gin and juices of all sorts. My breasts are always aching, particularly the left, the earnest one, which the baby refuses to favor. First comforts must be learned, I suppose. It’s a matter of exposure.

“I want to explain,” our unnamed narrator declares, but her mind seems to wander away from this mission almost immediately. Who is Jace, and where has he gone? We never really find out, but we do get puzzling, upsetting clues, like this one:

It has always been Jace only. We were children together. We lived in the same house. It was a big house on the water. Jace remembers it precisely. I remember it not as well. There were eleven people in that house and a dog beneath it, tied night and day to the pilings. Eleven of us and always a baby. It doesn’t seem reasonable now when I think on it, but there were always eleven of us and always a baby. The diapers and the tiny clothes, hanging out to dry, for years!

Is Jace the father of the baby? Is he the narrator’s brother? The tingling ambiguities remain as the story concludes, the narrator still waiting on a return that may or may not happen.

What makes Williams’ ambiguities resonate so strongly is her precise evocation of place. Her stories happen in real physical space, the concrete details of which often contrast strongly with her character’s abstracted consciousnesses. “Shorelines” is one of several Florida stories in the collection, and Williams writes authoritatively about the Sunshine State without devolving into the caricature or grotesquerie that pervades so much writing about Florida. (As a Floridian, nothing annoys me quite so much in fiction as certain writers’ tendencies to exoticize Florida).

“Shepherd” is another of Wiliams’ Florida stories. (And one of her dog stories. And grief stories. And unnamed-girl-hero stories). It is set in the Florida Keys, where Williams lived for some time—her early career was in doing research for the U.S. Navy Marine Laboratory in Siesta Key, Florida. (Williams’ best-selling book is actually a history and tour guide of the Florida Keys). “Shepherd” is a sad story, one of the most basic stories in literature, really: Your dog dies. The story is ultimately about perception. After the dog’s death, the girl’s boyfriend cannot comprehend her grief. He scolds her:

“I think you’re wonderful, but I think a little realism is in order here. You would stand and scream at that dog, darling.” …

“I wasn’t screaming,” she said. The dog had a famous trick. The girl would ask, “Do you love me?” and he would leap up, all fours, into her arms. Everyone had been amazed.

While most readers will sympathize with the girl, her boyfriend’s perspective introduces an unsettling ambiguity. And yet Williams, or at least her character, resolves some of this ambiguity in what I take to be the story’s thesis:

Silence was a thing entrusted to the animals, the girl thought. Many things that human words have harmed are restored again by the silence of animals.

Taking Care is a bipolar book. Florida is one of its poles. Maine, where Williams grew up, is the other. “Winter Chemistry” (originally published in a different version as “A Story about Friends”) is a Maine story. In “Winter Chemistry,” two teenage girls, bored, play at something they don’t have the language for yet. Their game entails spying on their chemistry teacher, whom they both maybe are in love with. The girls may not comprehend what their emerging sexuality entails, but they do feel the physical world. Consider Williams’ evocation of Maine’s winter:

The cold didn’t invent anything like the summer has a habit of doing and it didn’t disclose anything like the spring. It lay powerfully encamped—waiting, altering one’s ambitions, encouraging ends. The cold made for an ache, a restlessness and an irritation, and thinking that fell in odd and unemployable directions.

The story propels the aching duo in “odd and unemployable directions” — and towards an unexpected violence foreshadowed earlier in the summer, as the two munched chips on the beach, watching a pair of swimmers drown.

In “Train,” Williams gives us another pair of girls, Danica and Jane. They are traveling from Maine to Florida, traversing the poles of Williams’ Taking Care. They explore “the entire train, from north to south” and find most of the adults drunk, or at least getting there. Jane’s parents, the Muirheads, clearly, strongly, definitively out of love, are in a fight. The adult world’s authority is always under suspicion in Taking Care. And yet the adults in Williams’ stories see what the children cannot yet see:

“Do you think Jane and I will be friends forever?” Dan asked.

Mr. Muirhead looked surprised. “Definitely not. Jane will not have friends. Jane will have husbands, enemies and lawyers.” He cracked ice noisily with his white teeth. “I’m glad you enjoyed your summer, Dan, and I hope you’re enjoying your childhood. When you grow up, a shadow falls. Everything’s sunny and then this big Goddamn wing or something passes overhead.”

“Oh,” Dan said.

The theme of caretaking evinces most strongly in the titular story. “Taking Care” seems to be set in Maine, although it’s not entirely clear. The story focuses on “Jones, the preacher,” who “has been in love all his life”; indeed, “Jones’s love is much too apparent and it arouses neglect.” Jones takes care of himself only so that he can take care of others. His wife is diagnosed with cancer; his daughter, in the midst of a nervous breakdown, has run away to Mexico, leaving Jones to care for her infant daughter, his only grandchild. The story is devastating in its evocation of love and duty, and ends although its ending is ambiguous, it nevertheless concludes on an achingly-sweet grace note.

Jones’s enduring, patient love is unusual in Taking Care, where friendships splinter, marriages fail, and children realize their parents’ vices and frailties might be their true inheritance. These are stories of domestic doom and incipient madness, alcoholism and lost pets. There’s humor here, but the humor is ice dry, and never applied as even a palliative to the central sadness of Taking Care. Williams’ humor is something closer to cosmic absurdity, a recognition of the ambiguity at the core of being human, of not knowing. It’s the humor of two girls eating chips on a beach, unable to decide if the people they are gazing at are drowning or just having a good time.

I enjoyed many of the stories in “Taking Care” very much, and especially enjoyed the stranger, more formally-adventurous ones, like “The Lover” and “The Excursion.” I look forward to reading more of Joy Williams’ work. Highly recommended.

[Ed. — we first ran this review in March 2019.]

Saint Christopher (Detail) — Otto Dix

Saint Christopher (detail), 1938 by Otto Dix (1891-1969)

Caren Beilin’s Revenge of the Scapegoat is a funny, ludic novel about trauma and art

A book should be like a lot of spit. But who would publish me? Who publishes a person who’s sort of soaking in pain, who can’t always walk, employed only pretty much in name?

Did writing exist in books anyway these days? I thought perhaps defensively. Maybe it didn’t.

Writing does exist in books these days, despite what Iris, the narrator of a book of writing that exists, a book by Caren Beilin entitled Revenge of the Scapegoat, thinks perhaps defensively.

Iris, who will later transform into Vivitrix Marigold, thinks these defensive thoughts after receiving a package from her estranged father. The package contains two letters her father wrote to her when she was a teenager and a play she began but never finished composing when she was 17. The play had a title though: Billy the Id.

And why does Iris need defensive thoughts to defend her against this offensive package? Well, it turns out she was the designated scapegoat of her family, the atavistic locus for her father’s animus and her terminally-ill mother’s helplessness.

Mom’s dead now and Iris has escaped to Philadelphia, where she’s an underemployed adjunct teaching creative writing to overworked kids. She’s been “re-parented by the crucial cosmos, if poorly,” living in a house her mother left to her “like a moldy letter, black botches all over, and all over the counters.” Her mother had bought the house as an escape plan for Iris and her brother, but she never escaped (“She died of staying”). Iris lives in the moldy old house with her alcoholic husband. He lies about being a recovering alcoholic (“He told me that microdosing heroin was helping him in his recovery”). It’s clear that the marriage is failing.

But this isn’t a marriage story. It’s not her husband’s unremarkable departure, but rather the arrival of the packaged writing, that sparks Iris’s transformation. This transformation occurs over four distinct sections.

The first section is mostly a dialogue between Iris and her friend Ray, who is transitioning between genders. Like Iris, Ray was the designated scapegoat of their family, and the pair bonds and shares their trauma at a coffee shop called Good Karma. There’s a zaniness to Scapegoat that frequently veers into absurd humor and even outright surrealism (as when, for example, Iris punctuates her conversation with this observation: “The sun was going down. Holograms of dead parrots flopped in the road,” which I take to be Beilin’s oblique approximation of the old chestnut, “Somewhere in the distance a dog barked”). But the zaniness in Scapegoat is never precious or cloying; rather, the verbal quirks and eccentric images are anchored in the concrete pain and real trauma that Iris is trying to process.

Inspired by her conversation with Ray, Iris offers them her house in exchange for their boxy old Subaru. Iris drives and drives and drives, out into the New England countryside, repeatedly playing the same cassingle, one “SCAR” by Vivitrix Marigold. The poor Subaru, which “had more than 700,000 miles” on it, eventually gives out, and Iris finds herself stranded “out in the middle of a New England nowhere” — but not a poor nowhere, “No, this was all richie rich.”

It’s in this second section that Iris transforms into Vivitrix, and the narrative becomes even more surreal. It begins with our hero outside of an obscure art museum called The mARTin. There is a heart-stepping cow, of old Nazi stock, stepping on her heart. From there things get even weirder, and it would be a shame to spoil more of the plot. I don’t actually care about plot too much, but a lot of wild stuff: a curator who may or may not have murdered her husband, cowherding, a patricidal pervert, kale marmalade made from bull semen, castration conversation, a queasy dinner party (with a forced table reading of Billy the Id!) and more.

There’s also a very cathartic end, which I wasn’t anticipating. But it was lovely.

Perhaps ultimately the plot of Revenge of the Scapegoat is about transforming trauma into art, but as I write this sentence out, it seems like something Iris would tell her students not to do in their writing. Iris scatters her writing advice into the narrative and then breaks it: “Do not italicize foreign words”; “I told students there could be no rain or scenes on benches”; “Don’t write about food in an inventive way”. And my favorite: “Don’t make adult women reconcile or admit anything in your writing.”

In addition to this metatextual conceit, Beilin also employs the strange rhetorical device of turning Iris’s poor arthritic feet into Bouvard and Pécuchet, characters from Flaubert’s unfinished satire Bouvard et Pécuchet. At one point the pair bicker over which kind of precious metal or gem a witch might prefer. They are the not-quite-chorus of Revenge of the Scapegoat.

Beilen also lards her tale with similes that wonderfully strain credulity. On the first page, Iris compares the vegan leather of shoes to “a liquid you would press from a hot tampon you are pulling now, by the lamplight, out of a toad’s omnibus of Anaïs Nin.” Iris will often then puncture the artifice of the simile with rough reality: “I was shaking in the grass like an Etch-a-Sketch a higher power was trying to erase wholesale. Fuck that. I stopped shaking.” Or consider the surreal swell and bathetic pop in this passage, where Iris (now Vivitrix) compares her first encounter with The mARTin museum to the narrator of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” seeing the titular house for the first time:

Like that narrator, that man, so too I, Vivitrix, first looked at the reflective water rather than at a real building, weird, so I first saw The mARTin upside down. Its pink door stretched tall on morning’s mandible, as though it were flocked in flamingo leather, a pink surpassing the high heat of “hot,” a flamingo ultravinegar spilled all over something like a primed bookcover of a welcome new monograph on someone like Sade, or Wilde, someone such as Rimbaud or O’Hara, or Keats, men with honorary vaginas who castrated by love and the system, Flaubert, Adorno or Baldwin. It was a very pink door.

I’ve shared a taste of Beilin’s prose at length, and while I think it’s representative of the novel’s style, it can’t replace the feeling of how her sentences flow and build and ebb and swell. Initially, some of the verbal tics in Scapegoat irritated me, but it was the kind of irritation that makes you want to keep reading. And, a few pages after the lovely strange passage I’ve quoted above, our hungry hungry hero declares, “I needed some beef like you wouldn’t beleef.”

I laughed out loud and that initial irritation resolved into something like love. Highly recommended.

Revenge of the Scapegoat is available now from Dorothy.

[ed. — we first ran this review in June 2022.]

Debbie Urbanski’s Portalmania (Book acquired, 5 May 2025)

I really dug Debbie Urbanski’s debut novel After World, writing about it,

Debbie Urbanski’s debut novel After World reimagines the end of humanity—or perhaps the beginning of a new digital existence. The narrator, [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc, reconstructs the life of Sen Anon, the last human archived in the Digital Human Archive Project, using sources like drones, diaries, and other materials. Drawing on tropes from dystopian and post-apocalyptic literature, this metatextual novel references authors like Octavia Butler and Margaret Atwood while nodding to works such as House of Leaves and Station Eleven. Urbanski’s spare, post-postmodern approach also reminded me of David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress—good stuff.

Publisher Simon & Schuster’s blurb:

In Portalmania, Debbie Urbanski wields sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and realism to build a dark mirror that she holds up to the ordinary world. Within the sharply imagined landscape of this collection, portals appear in linen closets, planetary gateways materialize in boarding schools, monsters wait in bathroom vents, and transformations of women’s bodies are an everyday occurrence. Political division causes physical rifts that break apart the Earth’s crust. A son on another planet sends dispatches home to the mother who failed him, and a wife turns to the supernatural to escape her abusive marriage. Portals are not only doorways found in children’s classics, but separations, escapes, dead ends, desertions, and choices that will change these characters’ lives forever.

In the Echo Chamber — Leonor Fini

A review of Leonora Carrington’s surreal novel The Hearing Trumpet

Leonora Carrington’s novel The Hearing Trumpet begins with its nonagenarian narrator forced into a retirement home and ends in an ecstatic post-apocalyptic utopia “peopled with cats, werewolves, bees and goats.” In between all sorts of wild stuff happens. There’s a scheming New Age cult, a failed assassination attempt, a hunger strike, bee glade rituals, a witches sabbath, an angelic birth, a quest for the Holy Grail, and more, more, more.

Composed in the 1950s and first published in 1974, The Hearing Trumpet is new in print again for the first time in nearly two decades from NYRB. NYRB also published Carrington’s hallucinatory memoir Down Below a few years back, around the same time as Dorothy issued The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. Most people first come to know Carrington through her stunning, surreal paintings, which have been much more accessible (because of the internet) than her literature. However, Dorothy’s Complete Stories brought new attention to Carrington’s writing, a revival continued in this new edition of The Hearing Trumpet.

Readers familiar with Carrington’s surreal short stories might be surprised at the straightforward realism in the opening pages of The Hearing Trumpet. Ninety-two-year-old narrator Marian Leatherby lives a quiet life with her son and daughter-in-law and her tee-vee-loving grandson. They are English expatriates living in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country, and although the weather is pleasant, Marian dreams of the cold, “of going to Lapland to be drawn in a vehicle by dogs, woolly dogs.” She’s quite hard of hearing, but her sight is fine, and she sports “a short grey beard which conventional people would find repulsive.” Conventional people will soon be pushed to the margins in The Hearing Trumpet.

Marian’s life changes when her friend Carmella presents her with a hearing trumpet, a device “encrusted with silver and mother o’pearl motives and grandly curved like a buffalo’s horn.” At Carmella’s prompting, Marian uses the trumpet to spy on her son and daughter-in-law. To her horror, she learns they plan to send her to an old folks home. It’s not so much that she’ll miss her family—she directs the same nonchalance to them that she affords to even the most surreal events of the novel—it’s more the idea that she’ll have to conform to someone else’s rules (and, even worse, she may have to take part in organized sports!).

The old folks home is actually much, much stranger than Marian could have anticipated:

First impressions are never very clear, I can only say there seemed to be several courtyards , cloisters , stagnant fountains, trees, shrubs, lawns. The main building was in fact a castle, surrounded by various pavilions with incongruous shapes. Pixielike dwellings shaped like toadstools, Swiss chalets , railway carriages , one or two ordinary bungalows, something shaped like a boot, another like what I took to be an outsize Egyptian mummy. It was all so very strange that I for once doubted the accuracy of my observation.

The home’s rituals and procedures are even stranger. It is not a home for the aged; rather, it is “The Institute,” a cult-like operation founded on the principles of Dr. and Mrs. Gambit, two ridiculous and cruel villains who would not be out of place in a Roald Dahl novel. Dr. Gambit (possibly a parodic pastiche of George Gurdjieff and John Harvey Kellogg) represents all the avarice and hypocrisy of the twentieth century. His speech is a satire of the self-important and inflated language of commerce posing as philosophy, full of capitalized ideals: “Our Teaching,” “Inner Christianity,” “Self Remembering” and so on. Ultimately, it’s Gambit’s constricting and limited patriarchal view of psyche and spirit that the events in The Hearing Trumpet lambastes.

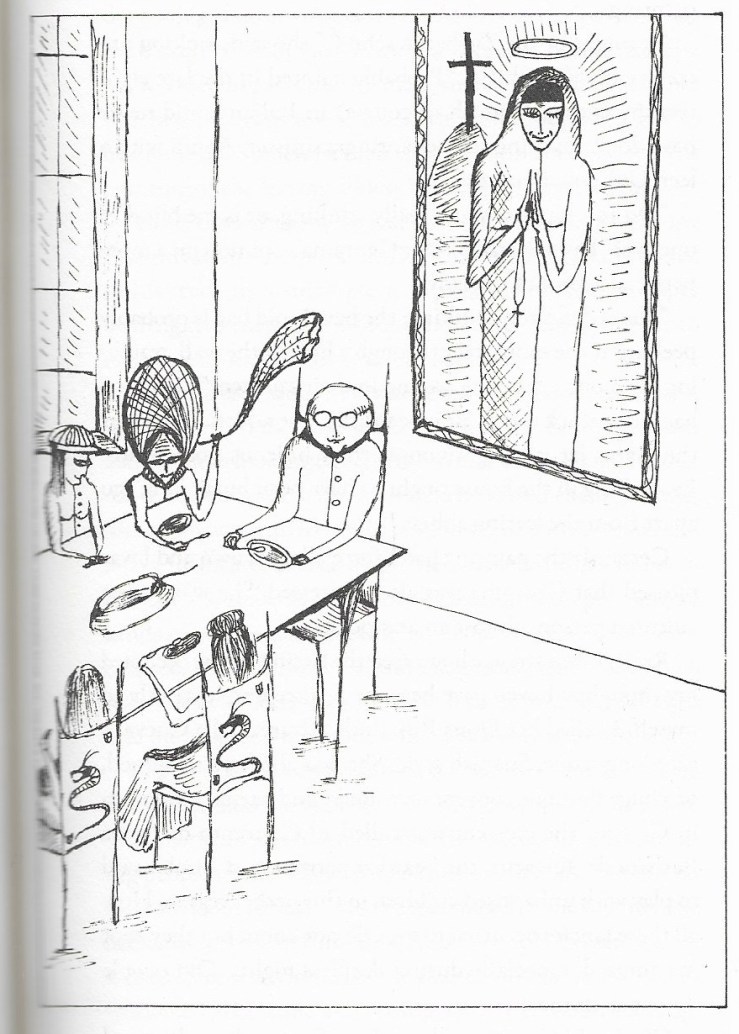

Marian soon finds herself entangled in the minor politics and scheming of the Institute, even as she remains something of an outsider on account of her deafness. She’s mostly concerned with getting an extra morsel of cauliflower at mealtimes—the Gambits keep the women undernourished. She eats her food quickly during the communal dinner, and obsesses over the portrait of a winking nun opposite her seat at the table:

Really it was strange how often the leering abbess occupied my thoughts. I even gave her a name, keeping it strictly to myself. I called her Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva, a nice long name, Spanish style. She was abbess, I imagined, of a huge Baroque convent on a lonely and barren mountain in Castile. The convent was called El Convento de Santa Barbara de Tartarus, the bearded patroness of Limbo said to play with unbaptised children in this nether region.

Marian’s creative invention of a “Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva” soon somehow passes into historical reality. First, she receives a letter from her trickster-aid Carmella, who has dreamed about a nun in a tower. “The winking nun could be no other than Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva,” remarks Marian. “How very mysterious that Carmella should have seen her telepathically.” Later, Christabel, another member/prisoner of the Institute helps usher Marian’s fantasy into reality. She confirms that Marian’s name for the nun is indeed true (kinda sorta): “‘That was her name during the eighteenth century,’ said Christabel. ‘But she has many many other names. She also enjoys different nationalities.'”

Christabel gives Marian a book entitled A True and Faithful Rendering of the Life of Rosalinda Alvarez and the next thirty-or-so pages gives way to this narrative. This text-within-a-text smuggles in other texts, including a lengthy letter from a bishop, as well as several ancient scrolls. There are conspiracies afoot, schemes to keep the Holy Grail out of the hands of the feminine power the Abbess embodies. There are magic potions and an immortal bard. There is cross-dressing and a strange monstrous pregnancy. There are the Knights Templar.

Carrington’s prose style in these texts-within-texts diverges considerably from the even, wry calm of Marian’s narration. In particular, there’s a sly control to the bishop’s letter, which reveals a bit-too-keen interest in teenage boys. These matryoshka sections showcase Carrington’s rhetorical range while also advancing the confounding plot. They recall The Courier’s Tragedy, the play nested in Thomas Pynchon’s 1965 novel The Crying of Lot 49. Both texts refer back to their metatexts, simultaneously explicating and confusing their audiences while advancing byzantine plot points and arcane themes.

Indeed, the tangled and surreal plot details of The Hearing Trumpet recall Pynchon’s oeuvre in general, but like Pynchon’s work, Carrington’s basic idea can be simplified to something like—Resistance to Them. Who is the Them? The patriarchy, the fascists, the killers. The liars, the cheaters, the ones who make war in the name of order. (One resister, the immortal traveling bard Taliesin, shows up in both the nested texts and later the metatext proper, where he arrives as a postman, recalling the Trystero of The Crying of Lot 49.)

The most overt voice of resistance is Marian’s best friend Carmella. Carmella initiates the novel by giving Marian the titular hearing trumpet, and she acts as a philosophical foil for her friend. Her constant warning that people under seventy and over seven should not be trusted becomes a refrain in the novel. Before Marian is shipped off to the Institution, Carmella already plans her escape, a scheme involving machine guns, rope, and other implements of adventure. Although she loves animals, Carmella is even willing to kill any police dogs that might guard the Institution and hamper their escape:

Police dogs are not properly speaking animals. Police dogs are perverted animals with no animal mentality. Policemen are not human beings so how can police dogs be animals?

Late in the novel, Carmella delivers perhaps the most straightforward thesis of The Hearing Trumpet:

It is impossible to understand how millions and millions of people all obey a sickly collection of gentlemen that call themselves ‘Government!’ The word, I expect, frightens people. It is a form of planetary hypnosis, and very unhealthy. Men are very difficult to understand… Let’s hope they all freeze to death. I am sure it would be very pleasant and healthy for human beings to have no authority whatever. They would have to think for themselves, instead of always being told what to do and think by advertisements, cinemas, policemen and parliaments.

Carmella’s dream of an anarchic utopia comes to pass.

How?

Well, there’s a lot to it, and I’d hate to spoil the surrealist fun. Let’s just say that Marian’s Grail quest scores a big apocalyptic win for the Goddess, thanks to “an army of bees, wolves, seven old women, a postman, a Chinaman, a poet, an atom-driven Ark, and a werewoman.” No conventional normies who might find Marian’s beard repulsive here.

With its conspiracy theories within conspiracy theories and Templar tales, The Hearing Trumpet will likely remind many readers of Umberto Eco’s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum (or one of its ripoffs). The Healing Trumpet’s surreal energy also recalls Angela Carter’s 1972 novel The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman. And of course, the highly-imagistic, ever-morphing language will recall Carrington’s own paintings, as well as those of her close friend Remedios Varo (who may have been the basis for Carmella), and their surrealist contemporaries (like Max Ernst) and forebears (like Hieronymus Bosch).

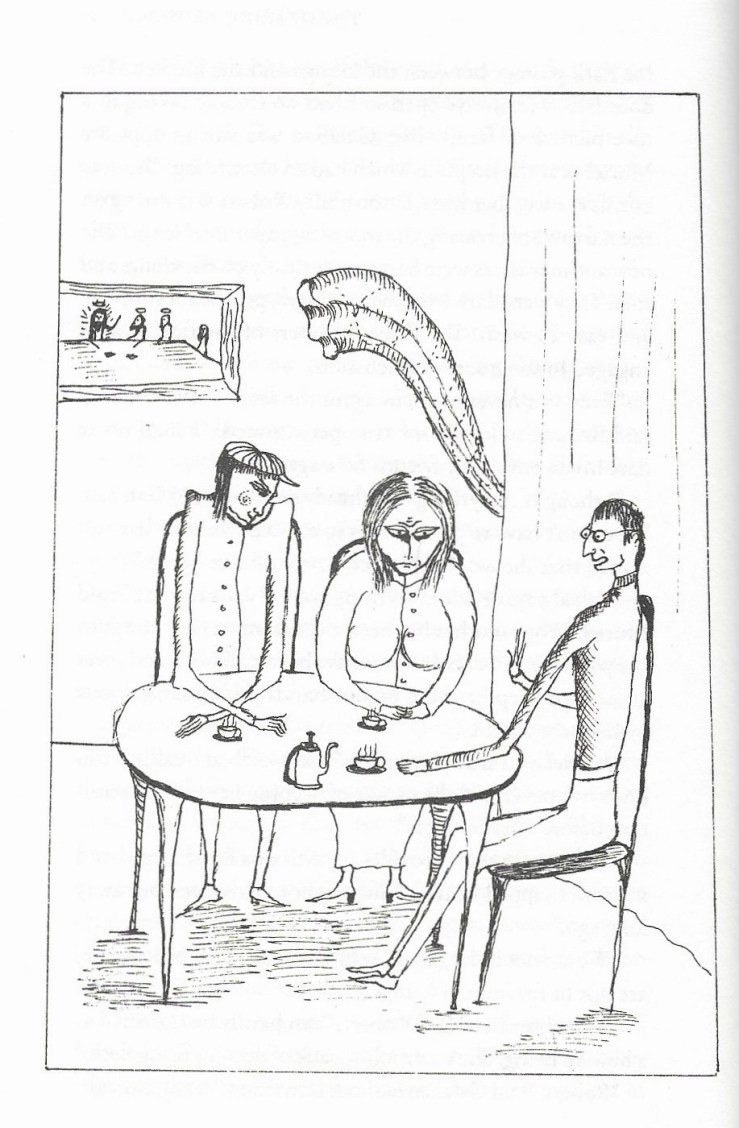

This new edition of The Hearing Trumpet includes an essay by the novelist Olga Tokarczuk (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones) which focuses on the novel as a feminist text. (Tokarczuk also mentions that she first read the novel without knowing who Carrington was). The new edition also includes black and white illustrations by Carrington’s son, Pablos Weisz Carrington (I’ve included a few in this review). As far as I can tell, these illustrations seem to be slightly different from the illustrations included in the 2004 edition of The Hearing Trumpet published by Exact Change. That 2004 edition has been out of print for ages and is somewhat hard (or really, expensive) to come by (I found a battered copy few years ago for forty bucks). NYRB’s new edition should reach the wider audience Carrington deserves.

Some readers will find the pacing of The Hearing Trumpet overwhelming, too frenetic. It moves like a snowball, gathering images, symbols, motifs into itself in an ever-growing, ever-speeding mass. Other readers may have difficulty with its ever-shifting plot. Nothing is stable in The Hearing Trumpet; everything is liable to mutate, morph, and transform. Those are my favorite kinds of novels though, and I loved The Hearing Trumpet—in particular, I loved its tone set against its imagery and plot. Marian’s narration is straightforward, occasionally wry, but hardly ever astonished or perplexed by the magical and wondrous events she takes part in. There’s a lot I likely missed in The Hearing Trouble—Carrington lards the novel with arcana, Jungian psychology, magical totems, and more more more—but I’m sure I’ll find more the next time I read it. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept first ran this review in December, 2020.]

Ann Quin’s novel Passages collapses hierarchies of center and margin

Ann Quin’s third novel Passages (1969) ostensibly tells the story of an unnamed woman and unnamed man traveling through an unnamed country in search of the woman’s brother, who may or may not be dead.

The adverb ostensibly is necessary in the previous sentence, because Passages does not actually tell that story—or it rather tells that story only glancingly, obliquely, and incompletely. Nevertheless, that is the apparent “plot” of Passages.

Quin is more interested in fractured/fracturing voices here. Passages pushes against the strictures of the traditional novel, eschewing character and plot development in favor of pure (and polluted) perceptions. There’s something schizophrenic about the voices in Passages. Interior monologues turn polyglossic or implode into elliptical fragments.

Quin repeatedly refuses to let her readers know where they stand. Indeed, we’re never quite sure of even the novel’s setting, which seems to be somewhere in the Mediterranean. It’s full of light and sea and sand and poverty, and the “political situation” is grim. (The woman’s brother’s disappearance may or may not have something to do with the region’s political instability.)

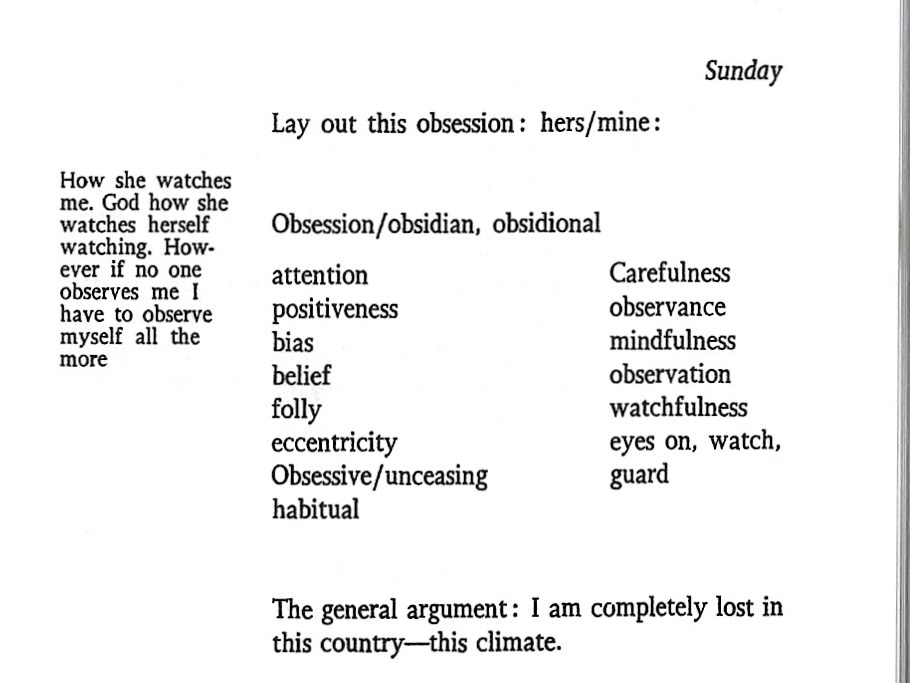

Passage’s content might be too slippery to stick to any traditional frame, but Quin employs a rhetorical conceit that teaches her reader how to read her novel. The book breaks into four unnamed chapters, each around twenty-five pages long. The first and third chapters find us loose in the woman’s stream of consciousness. The second and fourth chapters take the form of the man’s personal journal. These sections contain marginal annotations, which might be meant to represent actual physical annotations, or perhaps mental annotations–the man’s stream of consciousness while he rereads his journal.

Quin’s rhetorical strategy pays off, particularly in the book’s Sadean climax. This (literal) climax occurs at a carnivalesque party in a strange mansion on a small island. We see the events first through the woman’s perception, and then through the man’s. But I’ve gone too long without offering any representative language. Here’s a passage from the woman’s section, just a few paragraphs before the climax. To set the stage a bit, simply know that the woman plays voyeur to a bizarre threesome:

Mirrors faced each other. As the two turned, approached. Slower in movement in the centre, either side of him, turning back in the opposite direction to their first movement. Contours of their shadows indistinct. The first mirror reflected in the second. The second in the first. Images within images. Smaller than the last, one inside the other. She lay on the floor, wrists tied together. She bent back over the chair. He raised the whip, flung into space.

Later, the man’s perception of events at the party both clarify and cloud the woman’s account. As you can see in the excerpt above, the woman frequently refuses to qualify her pronouns in a way that might stabilize identities for her reader. Such obfuscation often happens in the course of a sentence or two:

I ran on, knowing I was being followed. She came to the edge, jumped into expanding blueness, ultra violet tilted as she went towards the beach. We walked in silence.

The woman’s I becomes a She and then merges into a We. The other half of that We is a He, the follower (“He later threw the bottle against the rocks”), but we soon realize that this He is not the male protagonist, but simply another He that the woman has taken as a one-time lover.

The woman frequently takes off somewhere to have sex with another man. At times the sex seems to be part of her quest to find her brother; other times it’s simply part of the novel’s dark, erotic tone. The man is undisturbed by his lover’s faithlessness. He is passive, depressive, and analytical, while she is manic and exuberant. Late in the novel he analyzes himself:

How many hours I waste lying in bed thinking about getting up. I see myself get up, go out, move, drink, eat, smile, turn, pay attention, talk, go up, go down. I am absent from that part, yet participating at the same time. A voyeur in all senses, in my actions, non-actions. What a delight it might be actually to get up without thinking, and then when dressed look back and still see myself curled up fast asleep under the blankets.

The man longs for a kind of split persona, an active agent to walk the world who can also gaze back at himself dormant, passive.

This motif of perception and observation echoes throughout Passages. Consider one of the man’s journal entries from early in the book:

Above, I used an image instead of text to give a sense of what the journal entries and their annotations look like. Here, the man’s annotation is a form of self-observation, self-analysis.

Other annotations dwell on describing myths or artifacts (often Greek or Talmudic). In a “December” entry, the man’s annotation is far lengthier than the text proper. The main entry reads:

I am on the verge of discovering my own demoniac possibilities and because of this I am conscious I am not alone with myself.

Again, we see the fracturing of identity, consciousness as ceaseless self-perception. The annotation is far more colorful in contrast:

An ancient tribe of the Kouretes were sorcerers and magicians. They invented statuary and discovered metals, and they were amphibious and of strange varieties of shape, some like demons, some like men, some like fishes, some like serpents, and some had no hands, some no feet, some had webs between their fingers like gees. They were blue-eyed and black-tailed. They perished struck down by the thunder of Zeus or by the arrows of Apollo.

Quin’s annotations dare her reader to make meaning—to put the fragments together in a way that might satisfy the traditional expectations we bring to a novel. But the meaning is always deferred, always slips away. Passages collapses notions of center and margin. As its title suggests, this is a novel about liminal people, liminal places.

The results are wonderfully frustrating. Passages is abject, even lurid at times, but also rich and even dazzling in moments, particularly in the woman’s chapters, which read like pure perception, untethered by traditional narrative expectations like causation, sequence, and chronology.

As such, Passages will not be every reader’s cup of tea. It lacks the sharp, grotesque humor of Quin’s first novel, Berg, and seems dead set at every angle to confound and even depress its readers. And yet there’s a wild possibility in Passages. In her introduction to the new edition of Passages recently published by And Other Stories, Claire-Louise Bennett tries to capture the feeling of reading Quin’s novel:

It’s difficult to describe — it’s almost like the omnipotent curiosity one burns with as an adolescent — sexual, solipsistic, melancholic, fierce, hungry, languorous — and without limit.

Bennett, whose anti-novel Pond bears the stamp of Quin’s influence, employs the right adjectives here. We could also add disorienting, challenging, abject and even distressing. While clearly influenced by Joyce and Beckett, Quin’s writing in Passages seems closer to William Burroughs’s ventriloquism and the hollowed-out alienation of Anna Kavan’s early work. Passages also points towards the writing of Kathy Acker, Alasdair Gray, and João Gilberto Noll, among others. But it’s ultimately its own weird thing, and half a century after its initial publication it still seems ahead of its time. Passages is clearly Not For Everyone but I loved it. Recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept originally posted this review in May 2021.]

Caza Nocturna — Remedios Varo

Caza Nocturna, 1958 by Remedios Varo (1908-1963)

A review of Dinah Brooke’s excellent cult novel Lord Jim at Home

Dinah Brooke’s 1973 novel Lord Jim at Home had been out of print for five decades — and had never gotten a U.S. release — until McNally Editions republished in 2023 with a new foreword by the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh. I always save forewords until after I’ve finished a novel, so I missed Moshfegh’s implicit advice to go into Lord Jim at Home cold. She notes that the recommendation she received to read it “came with no introduction,” and that “I wouldn’t have wanted the effect of the novel to be mitigated in any way, so I’m reluctant to introduce it now.”

I am not reluctant to write about Brooke’s novel because I am so enthusiastic about it and I think those with tastes in literature similar to my own will find something fascinating in its plot and prose. However, l agree with Moshfegh’s advice that Lord Jim at Home is best experienced free from as much mitigating context as possible. I had never heard of the novel before lifting it from a bookseller’s shelf, attracted by the striking cover; I flipped it over to read a blurb parsed from Moshfegh’s foreword attesting that Brooke’s novel “was an instrument of torture. It’s that good.” The inside flap informed me that reviews upon its publication “described it as ‘squalid and startling,’ ‘nastily horrific,’ and a ‘monstrous parody’ of upper-middle class English life.” I was sold.

Lord Jim at Home is squalid and startling and nastily horrific. It is abject, lurid, violent, and dark. It is also sad, absurd, mythic, often very funny, and somehow very, very real for all its strangeness. The novels I would most liken Lord Jim at Home to, at least in terms of the aesthetic and emotional experience of reading it, are Ann Quin’s Berg, Anna Kavan’s Ice, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and James Joyce’s Portrait (as well as bits of Ulysses). (I have not read Conrad’s Lord Jim, which Brooke has taken as something of a precursor text for Lord Jim at Home.)

After finishing Lord Jim at Home, I read it again by accident. At first I intended to take a few notes for a possible review, but after the first few pages I just kept reading. On a second reading, Brooke’s novel was just as strange—maybe even stranger—even if I was able to read it much more quickly, finding myself quicker to tune into the novel’s competing (and complementary) narrative registers. I found it far more precise, too, in the rhetorical development of its themes; Brooke’s styles and tones shift to capture the different ages of its hero. The novel begins in a mythical, archetypal mode and works its way through various registers, exploring the tropes of schoolboy novels, romances, war stories, adventure tales, modernism, realism, and journalism. But despite its shifting modes, Lord Jim at Home is not a parodic pastiche. Rather, at its core, Lord Jim at Home skewers how aesthetic modes—primarily those derived from notions of class and manners—cover over abject cruelty. As Moshfegh puts it in her forward, Lord Jim at Home is “an accurate portrayal of how fucked-up people behave, artfully conveyed in a way that nice people are too polite to admit they understand.”

I’ve tried to be clear that I think it’s best to come to Lord Jim at Home without too much context—it’s best to just go with the novel’s strangeness. Below, however, I offer a more detailed discussion of the novel, its language, and some elements of the plot for those so inclined.

Continue reading “A review of Dinah Brooke’s excellent cult novel Lord Jim at Home”

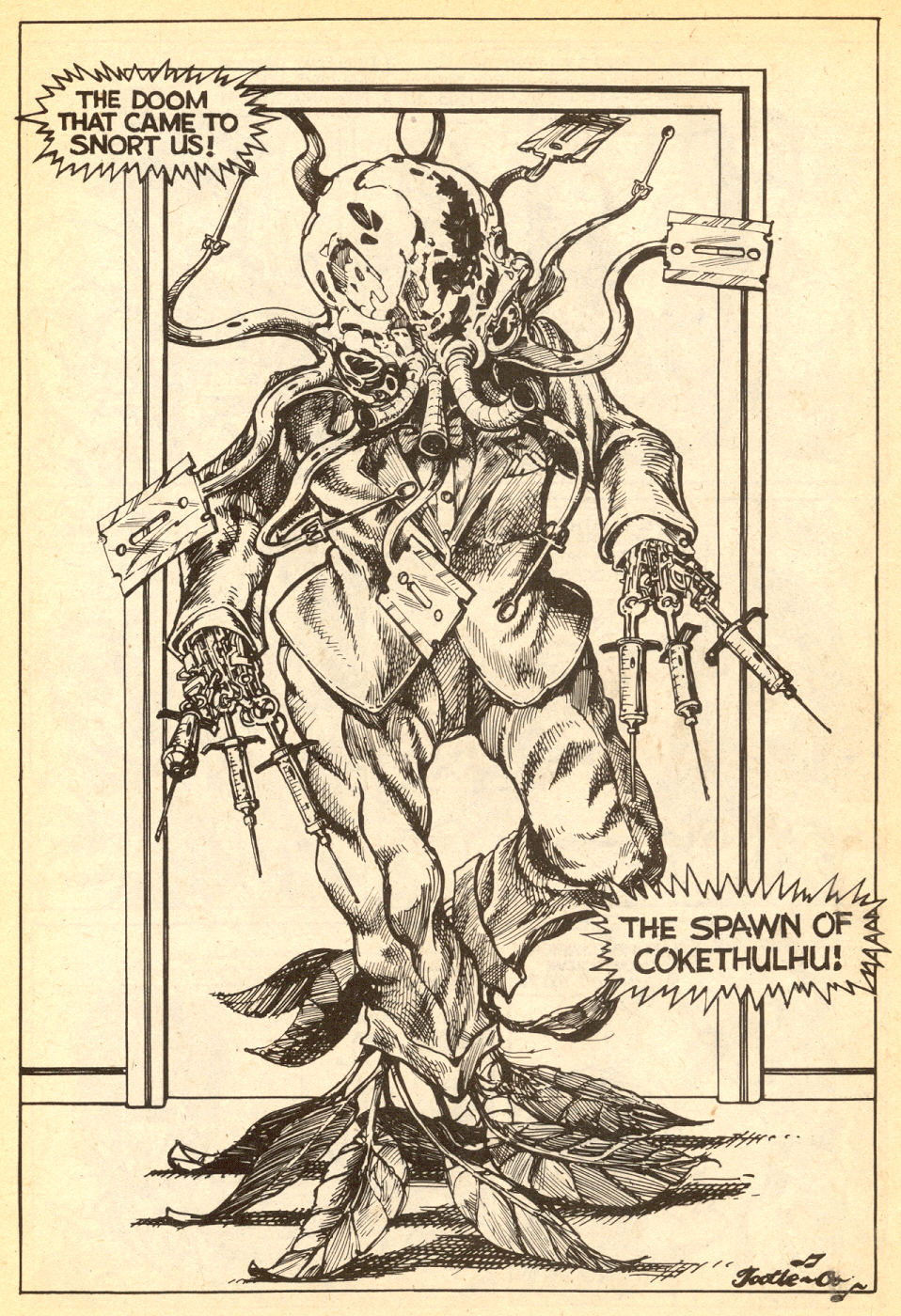

Sunday Comix

From “The Spawn of Cokethulhu” by Chris Statler, Cocaine Comix #2, 1981.

“The Story to End All Stories” — Philip K. Dick

“The Story to End All Stories”

by

Philip K. Dick

In a hydrogen war ravaged society the nubile young women go down to a futuristic zoo and have sexual intercourse with various deformed and non-human life forms in the cages. In this particular account a woman who has been patched together out of the damaged bodies of several women has intercourse with an alien female, there in the cage, and later on the woman, by means of futuristic science, conceives. The infant is born, and she and the female in the cage fight over it to see who gets it. The human young woman wins, and promptly eats the offspring, hair, teeth, toes and all. Just after she has finished she discovers that the offspring is God.

“The Charm of 5:30” — David Berman

“The Charm of 5:30”

by

David Berman

It’s too nice a day to read a novel set in England.

We’re within inches of the perfect distance from the sun,

the sky is blueberries and cream,

and the wind is as warm as air from a tire.

Even the headstones in the graveyard

seem to stand up and say “Hello! My name is…”

It’s enough to be sitting here on my porch,

thinking about Kermit Roosevelt,

following the course of an ant,

or walking out into the yard with a cordless phone

to find out she is going to be there tonight.

On a day like today, what looks like bad news in the distance

turns out to be something on my contact, carports and

white courtesy phones are spontaneously reappreciated

and random “okay”s ring through the backyards.

This morning I discovered the red tints in cola

when I held a glass of it up to the light

and found an expensive flashlight in the pocket of a winter coat

I was packing away for summer.

It all reminds me of that moment when you take off your

sunglasses after a long drive and realize it’s earlier

and lighter out than you had accounted for.

You know what I’m talking about,

and that’s the kind of fellowship that’s taking place in town, out in

the public spaces. You won’t overhear anyone using the words

“dramaturgy” or “state inspection” today. We’re too busy getting along.

It occurs to me that the laws are in the regions and the regions are

in the laws, and it feels good to say this, something that I’m almost

sure is true, outside under the sun.

Then to say it again, around friends, in the resonant voice of a

nineteenth-century senator, just for a lark.

There’s a shy looking fellow on the courthouse steps, holding up

a placard that says “But, I kinda liked Clinton.” His head turns slowly

as a beautiful girl walks by, holding a refrigerated bottle up against

her flushed cheek.

She smiles at me and I allow myself to imagine her walking into

town to buy lotion at a brick pharmacy.

When she gets home she’ll apply it with great lingering care

before moving into her parlor to play 78 records and drink gin-and-tonics

beside her homemade altar to James Madison.

In a town of this size, it’s certainly possible that I’ll be invited over

one night.

In fact I’ll bet you something.

Somewhere in the future I am remembering today. I’ll bet you

I’m remembering how I walked into the park at five thirty,

my favorite time of day, and how I found two cold pitchers

of just poured beer, sitting there on the bench.

I am remembering how my friend Chip showed up

with a catcher’s mask hanging from his belt and how I said

great to see you, sit down, have a beer, how are you,

and how he turned to me with the sunset reflecting off his

contacts and said, wonderful, how are you.

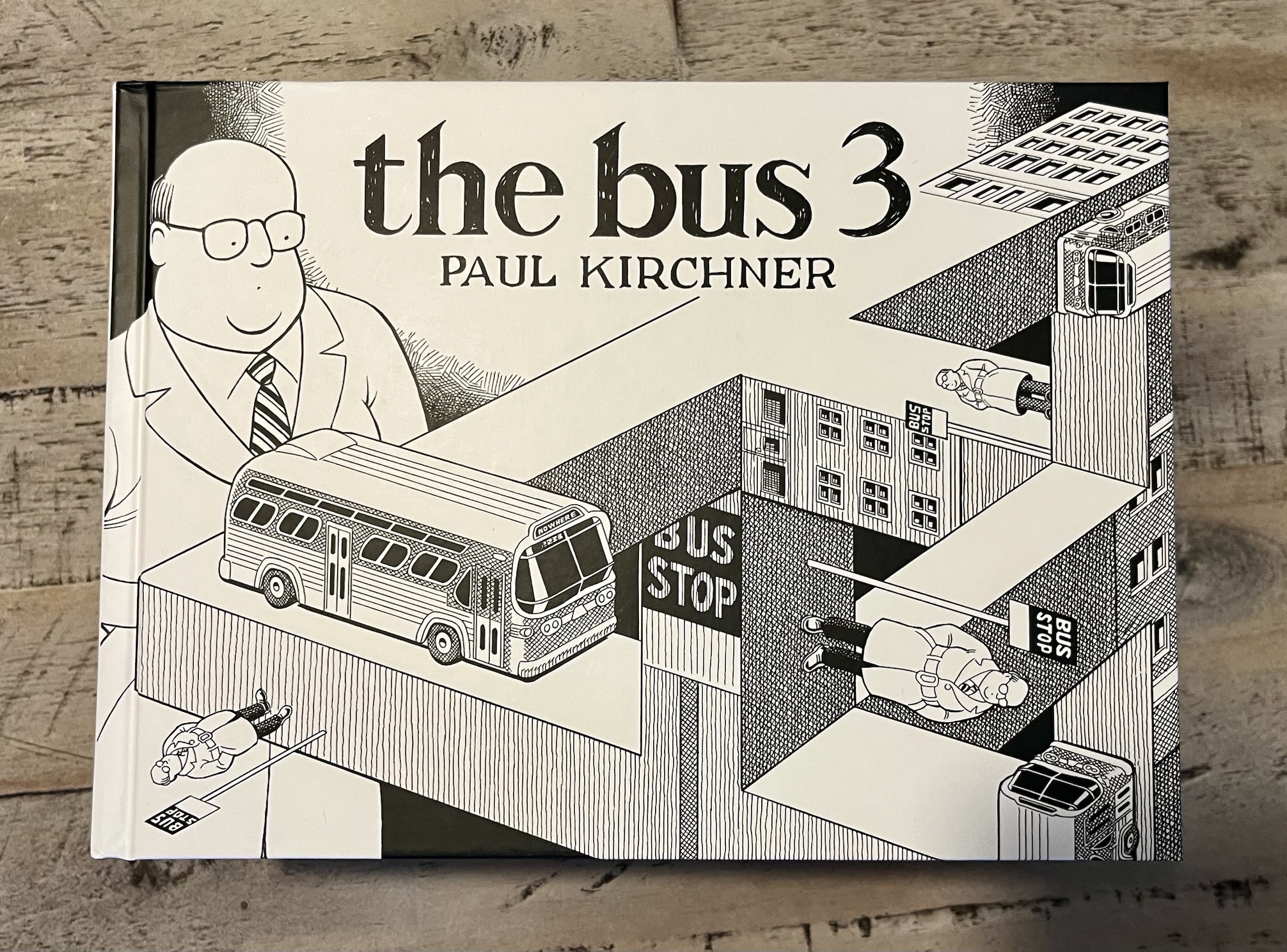

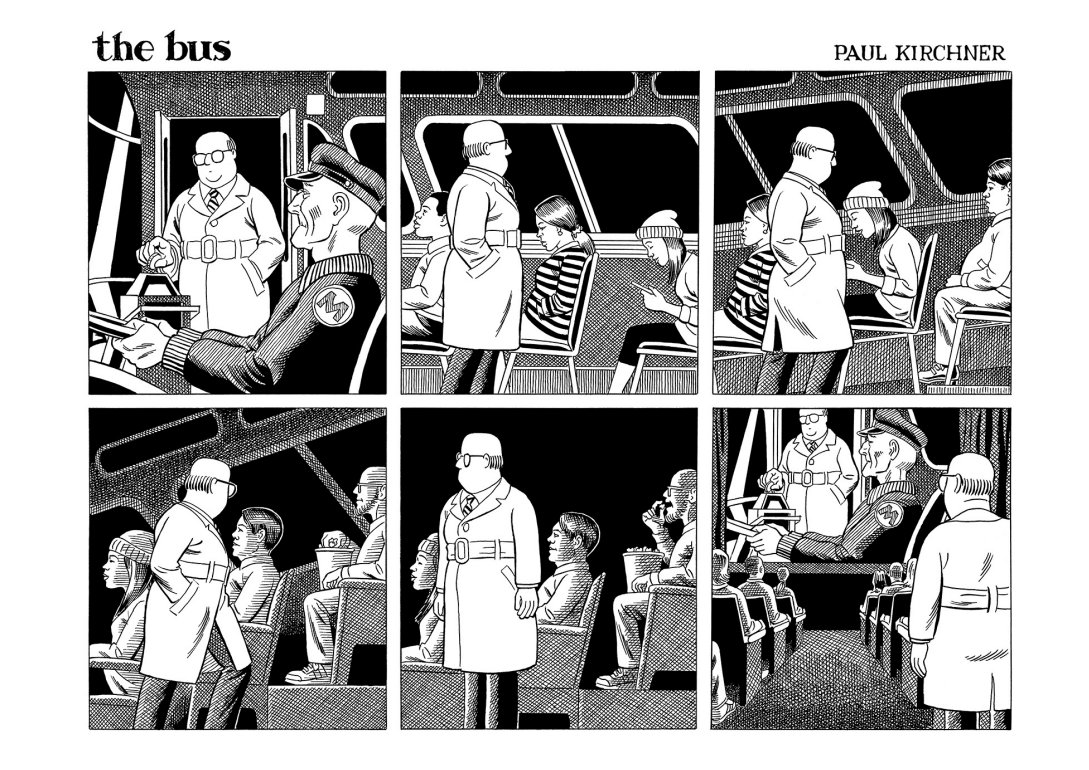

Paul Kirchner’s The Bus 3 (Book acquired, early May 2025)

Paul Kirchner’s surreal cult classic strip The Bus has another sequel. The Bus 3 is new from Tanibis Editions, which published The Bus 2 a decade ago along with a collection of the original Bus strips.

From my review of The Bus 2:

Paul Kirchner’s cult classic comic strip The Bus originally ran in Heavy Metal from 1979-1985. The (anti-)story of “a hapless commuter and a demonic bus” (as Kichner put it himself in a recent memoir at The Boston Globe), The Bus, at its finest moments, transcends our expectations for what a comic strip can and should do. Sure, Kirchner delivers the set-ups, gags, japes, and jests we expect from a cartoon—but more often than not The Bus surpasses the confines of its form and medium. Its protagonist The Commuter is an allegorical everyman, a passenger tripping through an absurd world. Kirchner’s strip often shows us ways to see that absurd world—which is of course our own absurd world—with fresh eyes.

Here is the first strip in The Bus 3:

More thoughts to come.