. ; , ; ; , , , . , , ; , – , . ; , ; , . ; , , ; . ” ‘ , ” : ” . ” , . , , . . ; , – . – ; ‘ . ; , , , . , . , , – . , , . , , . , , , , , . – . , . , , ; , . , , , ; , – , , . , ; . ; , ; , . , , . ; ; ; , . . – ; , . ” ? ” ; , ” , ” , ” . ” ” ? ” . , , ” ? ” ” , , ” . : ” , ‘ , . — — , — — . , : , . , , ; ; ‘ . , . ‘ ; . , , , . , , . ‘ ; , , . , , , ; . . . ‘ , . ‘ . , , . , , ; , . , ; , . . , . , , . ; , — — , — — , , . ‘ , ‘ , ‘ . , ‘ . ‘ . ‘ , ‘ ; ; , . ; ? — — , , ‘ , ‘ , ‘ , . ; . , , , ‘ . . ‘ , ‘ , ‘ . ‘ , , ‘ , , ; , , . , . . . ” ” – ! ” . . ” , ” . . ” , ‘ . , ; , , ( ) . , ; . , . , , , ” , . . : ” ‘ ? ” ” , ‘ ? ” . . ” ; . ” ” — — ? ” . . ” , ; , ” . ” ; . , ‘ . ; , ; ( ) . , : , . ” ” , , ” . ” , ” . . ” . , , , . ; ; ‘ . ; . ‘ ; , ‘ . ” ; ” , ” . , ” ‘ . ” ” , , ” . ” , ” , ” ‘ . . ” ” , ” . , ” ‘ . . ” ” , ” . . ” ? ” ” . ; , – . , . ; , ‘ . ‘ , . , ; ; ‘ . ‘ ; . ” . . ” ? ” . ” . . . ” , . ” , , ” ; ” . , , . , , . . ” ” , ” . ” , . ; ‘ , . . ” . ; . ” , ” . ” . . ” ” , ” . ” , . ” . . . , , , , , . , , . , . ‘ . , . , ; , , . . , . . . , . . . , . . . , . , ” , ” . ‘ ” , ” ‘ ‘ . ‘ . , . . ; , , . . ; , , , . ” , ” , , ” . ” , , , , , . , . ” , , ” . ; , – . . , , , – , , . . , . , , ; . , , , , ‘ . , . ” , , ” , ” ? ” ” , ” . . ” . ? . ” ” ? ” . ” . ” ” , ” . ” . , ; ‘ , , . , ” , , ” . ” . . ” , ” ; ( ) , : ” ! ” , . ” — — ? ” . ” ? ” . ” . . . ” , , . , . ‘ . ‘ , . ; , ; , . ‘ . ; ; ‘ ; , . , , ; , , , ! , , . ; , , , , , . ; , , ; ‘ , , . . , , . ‘ ( ) . : : , , . , . – . , , , , . ” . , ” , ” . . ” . ; ; ; , , . ‘ , , – , , . ; ; . . , . , , , . ; , . , . , , . , , ‘ . , ; , . . . ” . , ? ” . . ; , : ” . ? ” ” , ” . ” . ‘ — — . — — ; , . ” ” . ; , ” . , . , , ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” ? ” ” , ” . ” ? ” ” ? ” . . , , , ; . ” , ” . . ” . ” ” , ” . , ” ; , . ” . ” ! ” . , ” , , ? ” . ” , ” , ” ? ” ” , ” . ” ? ” ” , ” . . ” , ” . , . ” ? ” ” , , ” . ” , ” . , . ” . ” ” , ” . , ” . ” ; , , . . , . , . , . . , , , , , ; , , . . ” , ” . ” , . , ! , ? . ? , , ? , ; , , ‘ , . ” – , , , ; – , , . , , , ; , , , . . – , . ” . , ? ” . ” , . , ” , , , , – , , ( ) , , . ” , ? – ? ” ” , , ” , . , , ‘ ; . ; ; ( ) ; , . , . . ” . , , ” . ” , . ? ” ” , . , , ” . ” . . ” ” , , ” . ” , , , ” . ” . ” ” . ? ” . ” , , . , ” . ” ; . ” ” , – , . ” ” – , . . ” . ” , ” , ” ! ; ; , . , ; , : , , – . ” , , , , – – – . ; ; , . , . ” , , ” , ” ; , ; ‘ . . ‘ ; , ! ; , . , — — , ” , ” . ” ‘ , , . . , , , , ; . . , . , . , – – ; , , ‘ . , . ; — — , – , – , , — — . . ” , , ” . ” ? ” ; . ” , ” , ” . ; – , , . , ‘ — — ‘ — — , ; – ; , . . ” ” , ” , . ” ? , , , ” , . ” . ” ” , , ” . ” . ” . , . ” , ” . ” . ” ” , ” . ” . , ” , . ” , ; — — . . ” ” , ” , ” : . ; . ” ” , ” , ” , , . ; , , , ; ‘ ; ; , : , . . ; ; , , ‘ ‘ : , . ” , . ” , ” , . ” , , , ” , ” . . ; ; . , ; , , . , ; . ” ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ , ” , ‘ ; ” ; , . ” . ” , ” , ” . ” , , — — , . . , . , , , ‘ , . , , , . ( , , ) , . , ; , , . ( ‘ ) . ; , , ; , , – , , – – . , . , . , ; , – . , , , ( ) . , ; . . , – , , . , . ‘ . ; , . , , ; — — , , . : , , , . . , ; , . ” , ” ; ” . . ” , . , . ” , ” , ” . . ” ” , , ” , ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” . ” , . . ; , ; , . ” . ? ” . ” – , , ” . . ; , , ” , ” , ” . ” , . – , ; , . ; – ; , , ; , , , . , , , , , , ‘ , . , , ; , ‘ , . , , , , , , , , ; , , . ‘ ; . – – . , : . , , . ‘ , ; , ; ; , ; , . ” , , , ” ; , ” , ” . ” . ” ‘ . ” ! ” , ” ! ? ” . . ” ‘ , ” . ” , , . ” , , . ; . ; , ; , ( ) , ; . , , ; , ; – ; , . , ; ; , . , ‘ , . ” , , ” . : ” . , , , . , ‘ . , . ” , , ; . — — ; ; ; , . ; . , . . ‘ , , , . ; , . ‘ ; , , , , , , . , ; , . ‘ . , , , – , . ; , ; , , . , . , . ” , ” . , , ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” – . ” ” , ” . ” , , . ? ” ” , , ” , ” . . . ; ; , ; , . ” ; ‘ . ” , ” ; ” , . , . ” ” , ” ; ” . . — — ; . , ; , ; . ” ” , , ? ” . ” , ” . ” ; . , . ” ; ‘ , . ” , ” , , ” . ” , ” ” : , , ‘ , . , , , . ; ; . ” ? ” . ” , ” , ” . . . ” ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” . ” ” , , ” . ” : ? ” ; . ” , ” . ” . . ” ” , ” : ” — — , , ! ” . , . ” , ” , ” – : ? ” ; ” , ” . . ; , , ; , , . , , : ” . . . ” ; . , , ; – , . ; , , . , , . , , , , , . , ; , ‘ . . ; , ; , . . . ; . ‘ ; ; . ‘ ; : , , ? , , ? , , ; ; . . ” , ” . ” , , . , ” . ” , , . ” ” , ” . ” ; , ; . ; : ‘ . ” ‘ , . ” , ” : ” ; . ” ” , ” . . ” . , ? ” . ” . , . ? ” ” . ? ? ” ” . , ; ” . ” , , ” , ; ” ‘ . ” , . . ” , ? ” . ” , , ” , ” ‘ ; : . ” ” , ” . ” , , , ” . ” ‘ , , ” . ” , , ” . ” . ” . , , . ” ! ” . ” ! ” . . ; , ; . . , , : ‘ , ; , , ; , . , ; , , . , . , , . . , . . , , ; , . , , ; , ; , . ‘ ; ; . , , . ” , ” , ” . ” , , ; , . ; . ‘ . ; , ‘ . – . ; ; ; ‘ , – . ; . ” , ” ; ” , ; . ” , . ” , ” , ” . . , ; ; , , . , . ” ” , , ” . ” ? ” ‘ , . ” . , ” , . ” ; . ” ” , ! ” . ; , ” ‘ ? ” . ” , ; . ” ” , ” ; ” . ” ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , , , . . , , ‘ , ; , ‘ , , . ” , , , ; , , . . ” , ” , ” . ; , , . . . , . ; , , , . ” ; , ; , ; , , , . ; ‘ , . . , . , , , , . ” : . . , , ” ; . ” – , ” : ” ? ” , . , , ” . . ” . , ; , , . , ; . , ? , ; ; . , ; , , . ; . ; ; , , , , . , , . , , , ; , , ; . , . , . . , – ; , . ” , ” , ” ‘ . . . ” ” , ” . ” , ? ” ” , ” . ” , , . ‘ ! , . ” ” , ? ” . ” , . , ; , . ” , , , , . – ; , , , . . ” ! ! ” . ” . ” ” , , ” , ” . , . ” ” , ” . ” , . . ( — — . — — . . ) ; . ” ” , ” . ” ; , , , ; . , , ; ; . , . ” ” , , ” , – , ” . ” ” , ” . , , . ; , . , , – ; , , . . ; . ” , , ” . . . , . . , . ” , , ? ” ; , ” ? ” ; ” ? ” ” . , ” , ” . ” ” , , ” . ” , , . ” ” ‘ , , ” , ” . , ‘ ; ‘ , — — . . , , ‘ . ” ” , , ” , ” . ? ” ” ‘ , ” , , ” . ” ‘ ; ; , . , , . ” , ” . ” , ” , ” , ; . . ” ” ‘ , ” , . ” ! ” , . ” ! ? ” ” ‘ , , ” ; ” ? ” . ‘ ; ‘ , , . , , , , , . , . , ; . . ; – ; , . , , , . , , , , – . , , ; , , . ” , , ” , ” , . ” ” , , ” . ; ; , ” , ? ” ” ‘ , ” . ” . ” , , ; ; , , . . , ; , ” ! ‘ . , ” . ” , ? ? ” . ” , ; . ” ” ‘ , ” . , ; . ” ! ” , ; , , . ” , ” , – , ” , ‘ . ” . , . ” , , ” , ” . , ‘ . , , , ‘ . ” . ‘ , – , ; , , . ; , , . ” . , , , ” ; , . : ” , ” . ” , , ” , ; , . , . ” , ” , . , ” ‘ ? ” ” , ” , , . ” ? , , , ” . ” ‘ , ? , ; ‘ ; , ; ‘ , , , . ! ” ” , ; , ” . , . ” , . — — , , ? ‘ ; ‘ . ” ” , . , , ‘ , ” . ” ( ) , , , . — — ‘ , — — . ‘ ; , , . , , , , , , . , , , . , , . ” ” ? ” . . , , , . : ” . . . . — — , . . . . , , . . . . . ” , , ‘ . ” ‘ , ” , ” . ” ” , ” . ; , ” ? ” ” ‘ , , , ” . ” ‘ , ? ” . ” , ” ; , , ” ? ” . ” ‘ ! ” ” ? ” . . ” ? ” ” ‘ ! ” . ” . . ; , . , , . , . , , ? , , ? . . . . ” . ” , ” . , ” . , , ; , , ; ; , — — ! ; , , , ; , , . ” ” , ” , , ” , ‘ . ” — — — — ” , , . ” . ” , , ” , ” ? , ? , , . — — , . ; . ” ” , ” , ” , . ‘ , , . ” ” , . , ‘ ! ” . ” , ” : ” ? ” ” , , , ” . ” ‘ , ” ; ” , . ” ” , ” ; ” . ” , . ” , , ” , , ” ? ” ” , , , ” . ” , , ” . ” ; . , ? ” ” , , , , , ” . ” , . ? — — , , ! , ; , ; ? , , ? ‘ . ‘ , . , . ? ” ” , ” , ” . ” ” — — — — ‘ , , : . ” ” , ” . . ” , , ” . ” , , . , ‘ , . ; ‘ – ; , – . ! ” ” , , ” . ” . , , — — — — . , ; ; ( , ) ‘ . , . . ” , . ” , , ” . ” , , ; . , , . , . , , , . . ” , . ” , , , ” ; , . , . , , , , . ; , . ” , , ” ; ” , . , ‘ . , ‘ ‘ ! , , ‘ ! , — — , . , , ‘ ? ” , , ; . . ” ? ” . . ” , ” . ” ! ” ” ? ? ” , . ” , ” . ” , . ” . ; ; , , . ” , ” , , ” . ” , . ” , , , ” ; ” , — — , ! ” ” , ” , ” ‘ , ! ” ” , ‘ ‘ — — ‘ ‘ ! ” . ” , ! ” ; , . , , . , ; ; ; , . , , . , , , , , , ; , , , , . . , . , ‘ ; , ; , – . ” , ” , ” . ; . ” , , , . – ; . . . , , , , . , , , ‘ ; , . , . . ” , ” , . ” , ” , – . ; , , . ” , ” . ” ! ” . ” , , ? . ” ” , ” , ” , , . ” . ” , , ” . ” . ” , , . , , , . ” , ” ; , . , – , ‘ , . ; , , , , . , , – , . , , . ” , , ” . ” , ” . ” ” — — , — — ” ? ” . ” ! ” . . , , , , ‘ , . . , . , , ; , , . , , . ” , ” . ” ; ; ; . ” ; ‘ . ” ! ” , ” . ; , ! , ? ? , ? , . . ” ” ‘ , ? ” . ” , ” . ” ! ” : ” , — — , , , . , ; , ” , ” . ” ” ? ” . ” , , ” , . . ” . , . ; ; , . ” , ; , , . . ‘ , , , , . ; ; , , , ; . ; : ” , — — . ” , — — ; , , , . , , ‘ , , , , , ‘ . , , , , ; – , . , , . . ” – — — , ; , ; , . , , ; . ; ; ( ) , ; , , ( ) . , ; , : , . . ” : . , , ; , , . , , , , . . , , ; , , . ” , . , , , , , . , ” , ” . . ” . . — — . – , – . , , ; . ; , . ” , ; , . , ; . , , ‘ . ; , . ; . ‘ , ( ) ‘ . , ; , ; . , ‘ , . ; , , . . , ; ‘ ; . , , – , . . . , . , : ” ” ; , ” ! ! ! ” , , . , ( ‘ ) . , , ? , ? , ? ; , , – . ‘ , . , . ” . ? ” . ” ” ; , . , ‘ ; , . , , ; , . , , . , . , ; , , — — — — , . , . , , , ; , . ( , , ) ; , , , — — , , . , . , — — , — — ; ‘ , , , . , , . , , . ” ? ” . ” ? ” . , . ” , , ” . ” . , . ” , , , , , . ” , . , ” . ” ; . , . , ; . . . ” , , , — — ” , . . . ” ‘ , . ” , , ” , , . , , ; ; . ” , ” . , , . , . , , ” ? ” . . , . , , , , , , . , , . , , , , . ” , ” , ” . ? ? ? ? , . , , , . , , , , , ; . ” ” , ” , , ” , . . ” ” , ” . ” , : . , , , — — ! ” . ; , , , , ; , , — — — — — — , , , . ” ! ” , ” ! ” ; — — , , , — — ! , . , , ; , , . ; ; ; , ; . , , , , . , , ( ) . , ‘ , . . ‘ — — , , , , , , . , , , . ; , , . ; , . , , , , ‘ . , , . – , ; ; , , , . , , . , , , , : , . , . , ; , . , , , . , , ; , , , ; , , , , . , , , ; , ; , , . — — , . , ? , , . , , , . , . , . , ‘ , , . , , , ! , . , , , , , . . ; , , , . . ; , , , , ; , , , , , . : , , . , . , , , . , , ; , , , . , , , , ; , , . , ; , . , , ; , . , — — , , — — ; , , . , , , , ; , ; , . , , . , , . , , , , , , . , , , . , . ( ) . , , . , , . . , , . . , . , , , , : , , . : ; ; , , , , . – . , , , , . ; ; ; , . ; , , ; . , , , , . . , . ; ( ) , , , . . , , , , . ; ; . , ; . , . ( ) ; , , . ; . , . , , , . , . . , , , . , , . — — ! , ; , ; , , , , . , , ; . , . , . , , ; ; ; . ; , . , , , . ; ; , , . . ( ) ; . , , . – , ; ‘ ; ; , , , . , ; , , , . , , , . ; ; ; , , . , , , , , . , , . ( ) ; , , . , , – , , , , , . . , , ; . , . , , . ? ; , — — ? ; ; — — , , , – . ; , ? , . , , : , . ; , . , , . . , , , , ; . , ; , ( ) ; , , , , . . , , ; , , , ; . , , ‘ , , , , . ; , . , . , . ( ) , , ; , . ‘ ; ‘ . , . , , , , . ; ; , . , ; ; , , . , , ; , , , , . , , , . , , ; , , . ; ; , ; , , . , , , ; , , , . . , . , , , . , , ; , , , ; . ; , , , . . , , ; , , , . ; ; , , , . , ( ) ; , , , – , . , , . , , , . – . : , ‘ , – , , , . ; ; , , . , . . ; , ; , ! ! , ! , , , . , . ; . ; , . ; . , , ; , , . ; ; ; , , , , . ; : , ; . ; ; . ; , . , , , , ; ‘ . ; ; , , . , , ; , , – . , , . , ; , , , , . ; ; . . ‘ , , — — – ; , , , , . , . , ; , , . ; ? ( ) . . , . , . ? ? , ? , , , . ? , : ; , . , , , , . ( , ) . ; — — — — , . , , ; ; , , . ; , , . ; ; , ; , . , , ; , , ; , , , . , — — , . ; . , , , , , , . , , , , . , , , . , . ‘ , : ; . . , . ‘ ; . , . , , . , ; , ; . , , ; , . ; ! , , , – . , , , . , ; , , , . , , , , , , , : . , , ( ) , , . . . , . , – : , , , , . ; ; ; , , . , , ; , ; , , , . . , ; , , . – , , ; , , . ; : , , , , . , , ; , ; , — — , — — , ; , , . , , . ; , , ; . ; ; , . , . , , , , ( ! ) . ; , . , ; , – . . , , , , , ( ) . ? ? ; ; , . , , .

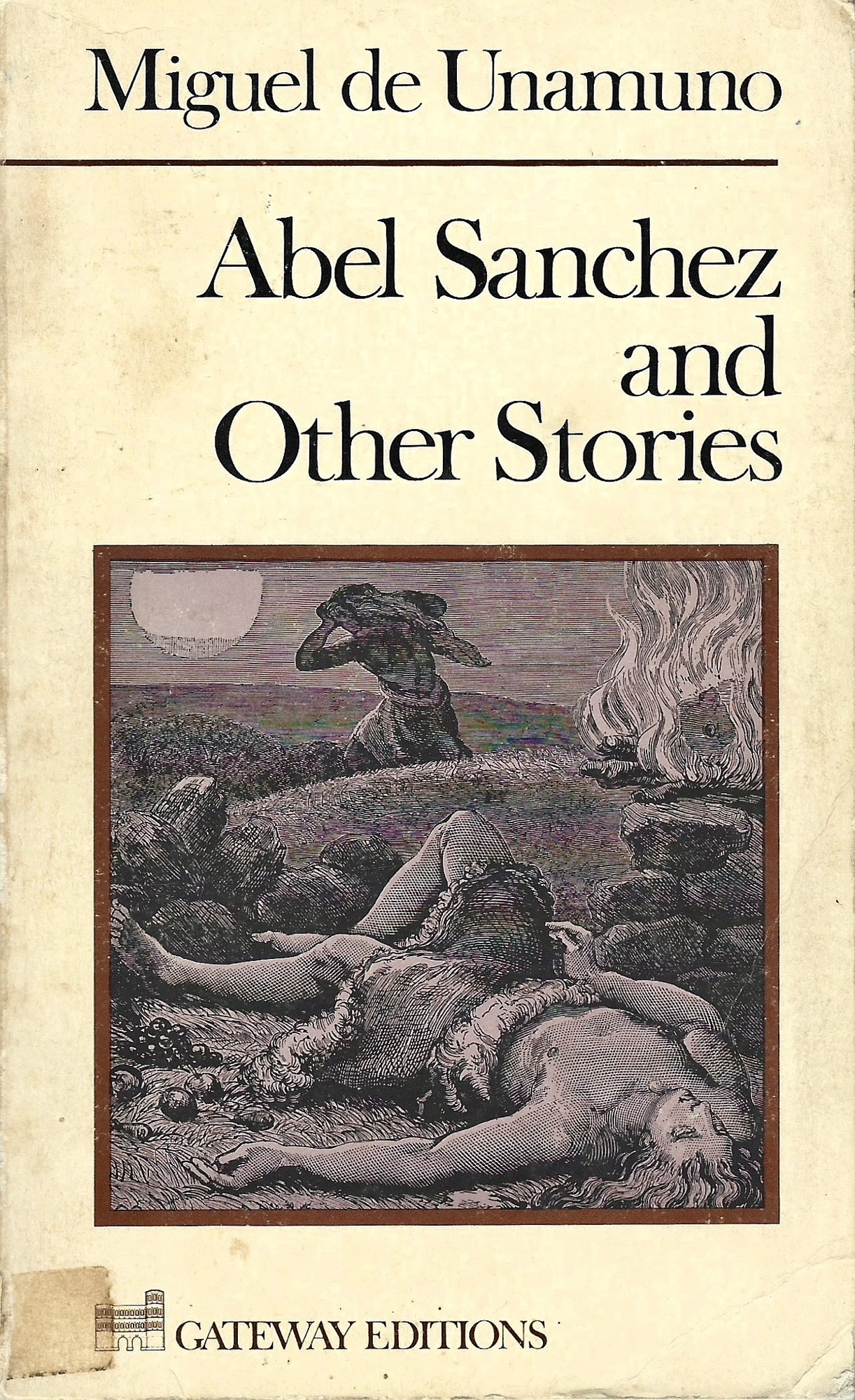

Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—but just the punctuation.