A page from Tales Designed to Thrizzle, no. 4, 2008, by Michael Kupperman (b. 1966)

Author: Biblioklept

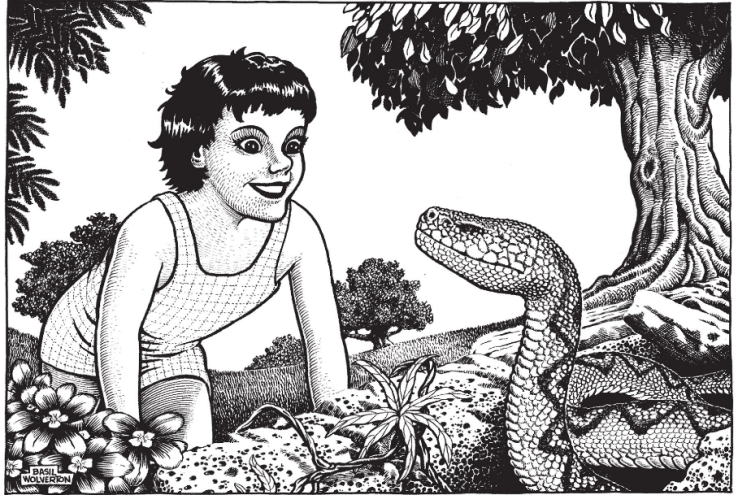

The infant will play near the hole of the cobra and the young child put his hand into the viper’s nest | Basil Wolverton

Illustration for Isaiah 11:8 by Basil Wolverton (1909-1978)

Club Night — George Bellows

Club Night, 1907 by George Bellows (1882-1925)

The familiar story of virgin birth on December twenty-fifth, mutilation and resurrection | From William Gaddis’s The Recognitions

His father seemed less than ever interested in what passed around him, once assured Wyatt’s illness was done. Except for the Sunday sermon, public activities in the town concerned him less than ever. Like Pliny, retiring to his Laurentine villa when Saturnalia approached, the Reverend Gwyon avoided the bleak festivities of his congregation whenever they occurred, by retiring to his study. But his disinterest was no longer a dark mantle of preoccupation. A sort of hazardous assurance had taken its place. He approached his Sunday sermons with complaisant audacity, introducing, for instance, druidical reverence for the oak tree as divinely favored because so often singled out to be struck by lightning. Through all of this, even to the sermon on the Aurora Borealis, the Dark Day of May in 1790 whose night moon turned to blood, and the great falling of stars in November 1833, as signs of the Second Advent, Aunt May might well have noted the persistent non-appearance of what she, from that same pulpit, had been shown as the body of Christ. Certainly the present members of the Use-Me Society found many of his references “unnecessary.” It did not seem quite necessary, for instance, to note that Moses had been accused of witchcraft in the Koran; that the hundred thousand converts to Christianity in the first two or three centuries in Rome were “slaves and disreputable people,” that in a town on the Nile there were ten thousand “shaggy monks” and twice that number of “god- dedicated virgins”; that Charlemagne mass-baptized Saxons by driving them through a river being blessed upstream by his bishops, while Saint Olaf made his subjects choose between baptism and death. No soberly tolerated feast day came round, but that Reverend Gwyon managed to herald its grim observation by allusion to some pagan ceremony which sounded uncomfortably like having a good time. Still the gray faces kept peace, precarious though it might be. They had never been treated this way from the pulpit. True, many stirred with indignant discomfort after listening to the familiar story of virgin birth on December twenty-fifth, mutilation and resurrection, to find they had been attending, not Christ, but Bacchus, Osiris, Krishna, Buddha, Adonis, Marduk, Balder, Attis, Amphion, or Quetzalcoatl. They recalled the sad day the sun was darkened; but they did not remember the occasion as being the death of Julius Caesar. And many hurried home to closet themselves with their Bibles after the sermon on the Trinity, which proved to be Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva; as they did after the recital of the Immaculate Conception, where the seed entered in spiritual form, bringing forth, in virginal modesty, Romulus and Remus.

If the mild assuasive tones of the Reverend offended anywhere, it was the proprietary sense of his congregation; and with true Puritan fortitude they resisted any suggestion that their bloody sacraments might have known other voices and other rooms. They could hardly know that the Reverend’s powers of resistance were being taxed more heavily than their own, where he withstood the temptation to tell them details of the Last Supper at the Eleusinian Mysteries, the snake in the Garden of Eden, what early translators of the Bible chose to let the word ‘thigh’ stand for (where ancient Hebrews placed their hands when under oath), the symbolism of the Triune triangle and, in generative counterpart so distressing to early fathers of the Church, the origin of the Cross.

Merry Christmas to All (Peanuts)

Merry Xmas with T-1 Space Suits — Eduardo Paolozzi

Merry Xmas with T-1 Space Suits (from Bunk), 1972 by Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005)

Ernst Jünger’s On the Marble Cliffs (Book acquired, 19 Dec. 2022)

Early next year, NYRB will publish Tess Lewis’s new translation of Ernst Jünger’s 1939 novella On the Marble Steps. NYRB’s blurb:

Set in a world of its own, Ernst Jünger’s On the Marble Cliffs is both a mesmerizing work of fantasy and an allegory of the advent of fascism. The narrator of the book and his brother, Otho, live in an ancient house carved out of the great marble cliffs that overlook the Marina, a great and beautiful lake that is surrounded by a peaceable land of ancient cities and temples and flourishing vineyards. To the north of the cliffs are the grasslands of the Campagna, occupied by herders. North of that, the great forest begins. There the brutal Head Forester rules, abetted by the warrior bands of the Mauretanians.

The brothers have seen all too much of war. Their youth was consumed in fighting. Now they have resolved to live quietly, studying botany, adding to their herbarium, consulting the books in their library, involving themselves in the timeless pursuit of knowledge. However, rumors of dark deeds begin to reach them in their sanctuary. Agents of the Head Forester are infiltrating the peaceful provinces he views with contempt, while peace itself, it seems, may only be a mask for heedlessness.

“Christmas on Lipponia” — Moebius

L’Hôtel Sully, Courtyard with Figures — Peter Rose Pulham

L’Hôtel Sully, Courtyard with Figures, c. 1944–5 by Peter Rose Pulham (1910-1956)

The freed and missing passenger | Joy Williams on Cormac McCarthy’s latest novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris

At Harper’s, novelist Joy Williams has a nice long essay on Cormac McCarthy’s novels The Passenger and Stella Maris. Williams begins with a concern that I think is fundamental to reading these novels: How do they talk to each other?

Cormac McCarthy’s latest offering—in that word’s fundamentally spiritual sense—is The Passenger and its coda or addendum, Stella Maris. One is prompted to read The Passenger first (it came out in October) and Stella Maris second (it came out in December). If, however, you dare to test the trickster and begin with Stella Maris—a 189-page conversation between a psychiatrist and his patient—it will seriously trouble your perception of The Passenger. If you read the books in order, you might find Stella Maris (Latin for Star of the Sea, a psychiatric hospital in Black River Falls, Wisconsin) coldly underwhelming despite, or perhaps because of, the erudition of the twenty-one-year-old, debatably schizophrenic, suicidal math genius Alice Western.

Williams focuses heavily on Stella Maris at the outset of her essay, offering a stable timeline for the two novels. If you’ve read The Passenger and Stella Maris, you know that McCarthy withholds a linear, chronological plot. Williams’ plot-making though foregrounds something that’s easy to miss in a first-reading of The Passenger: Bobby is in a coma, officially brain dead after a racing accident. Williams writes that,

The invention of brain death serves the timeline of The Passenger well, and traversing this twisting line, tracing and retracing it, contesting it, surrendering to it, is one of the great and pleasurable challenges of these books. Is there a narrative line? The Kid thinks it’s important to locate one even if, as he says, it doesn’t hold up in court. As for McCarthy, plot has always been irrelevant to his purposes.

What are those purposes?

McCarthy is not interested in the psychology of character. He probably never has been. He’s interested in the horror of every living creature’s situation.

–and–

Cormac McCarthy is interested in . . . the unconscious and in the distaste for language the unconscious harbors and the mystery of the evolution of language, which chose only one species to evolve in. He’s interested in the preposterous acceptance that one thing—a sound that becomes a word—can refer to another thing, mean another thing, replacing the world bit by bit with what can be said about it.

–and–

. . . the overwhelming subject is the soul. Where can it be found? By what means does it travel? Is it frightened when we take leave of it? Can it find rest in the darkness? Animula vagula blandula. The soul. The freed and missing passenger.

I could continue to cherrypick at Williams’ essay, but will instead simply recommend you read it yourself. There’s all kinds of insights there—McCarthy’s weakness in portraying women; the homelessness motif of The Passenger; a brief cataloging of his oeuvre to date.

For me, the most interesting idea in Williams’ essay–which she never directly states–is that Bobby is actually brain dead and that the events in his chapters of The Passenger take place in his unconscious mind.

Williams’ essay was the first (and so far only) review of McCarthy’s latest novels that I’ve read. Thanks to BLCKDGRD for sending a scan of his physical copy my way last week.

To escape the insidious commercial excesses of Christmas (Glen Baxter)

The Clairvoyant — John Currin

The Clairvoyant, 2001 by John Currin (b. 1962)

Continuously I receive it but do not accept it | Kafka’s diary, 18 Dec. 1910

18 December. If it were not absolutely certain that the reason why I permit letters (even those that may be foreseen to have insignificant contents, like this present one) to lie unopened for a time is only weakness and cowardice, which hesitate as much to open a letter as they would hesitate to open the door of a room in which someone, already impatient, perhaps, is waiting for me, then one could explain this allowing of letters to lie even better as thoroughness. That is to say, assuming that I am a thorough person, then I must attempt to protract everything pertaining to the letter to the greatest possible extent. I must open it slowly, read it, slowly and often, consider it for a long time, prepare a clean copy after many drafts, and finally delay even the posting. All this lies within my power, only the sudden receipt of the letter cannot be avoided. Well, I slow even that down in an artificial manner, I do not open it for a long time, it lies on the table before me, it continuously offers itself to me, continuously I receive it but do not accept it.

From Franz Kafka’s diary entry of 18 Dec. 1910. Translated by Joseph Kresh. (I feel the same way about email.)

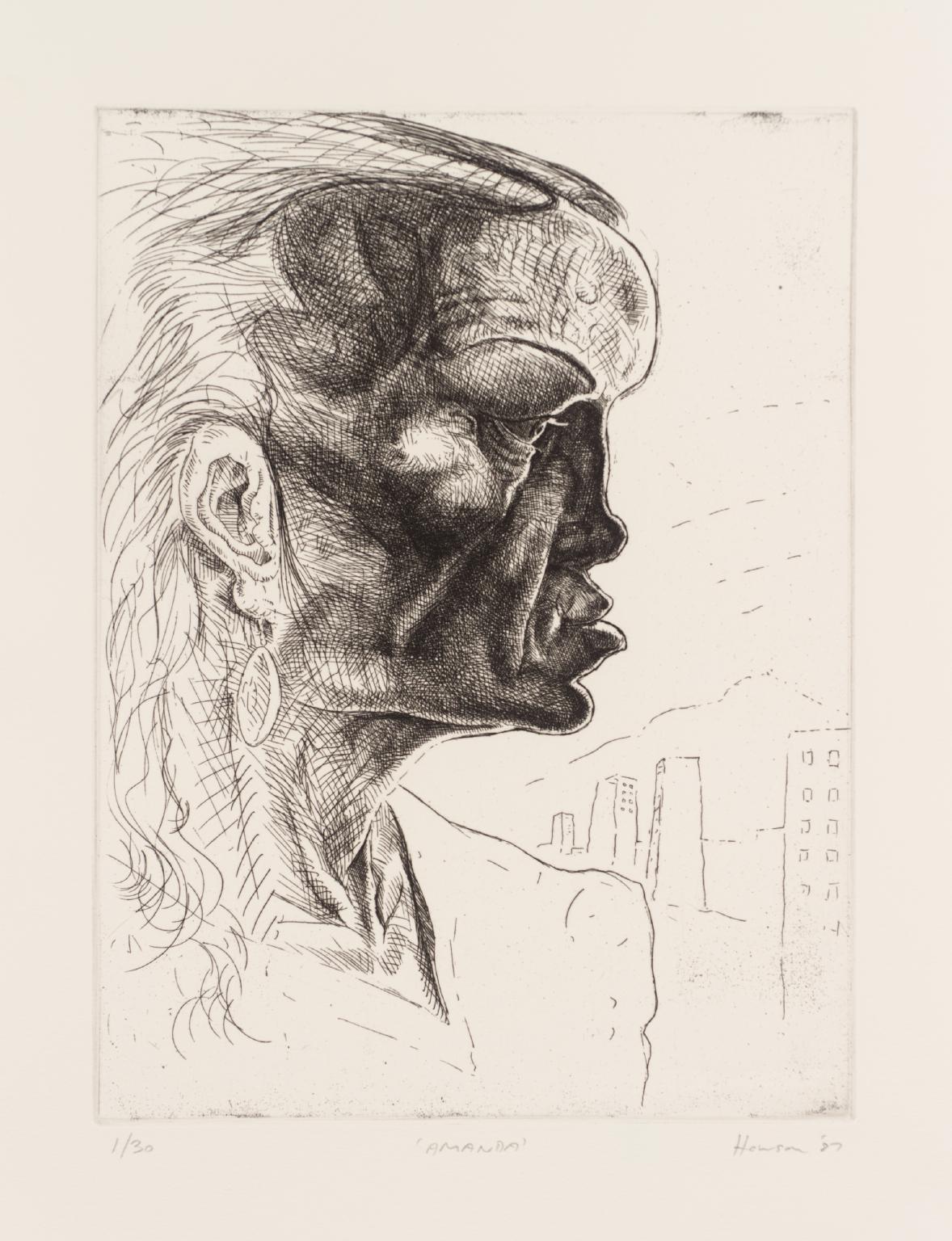

Amanda — Peter Howson

Amanda, 1987 by Peter Howson (b. 1958)

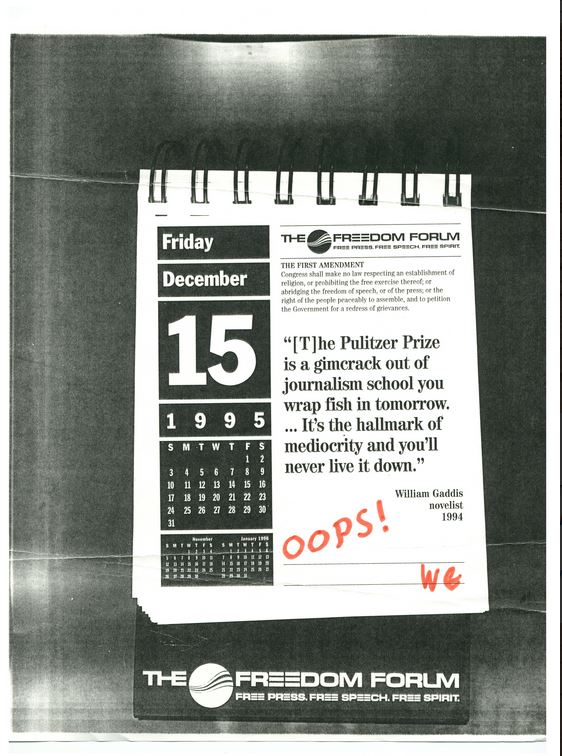

OOPS! (William Gaddis)

Another little nugget from Washington University’s Modern Literature collection. Their description:

The Freedom Forum calendar showing a quote concerning the Pulitzer Prize by William Gaddis on December 15, 1995. Includes autograph commentary by Gaddis.

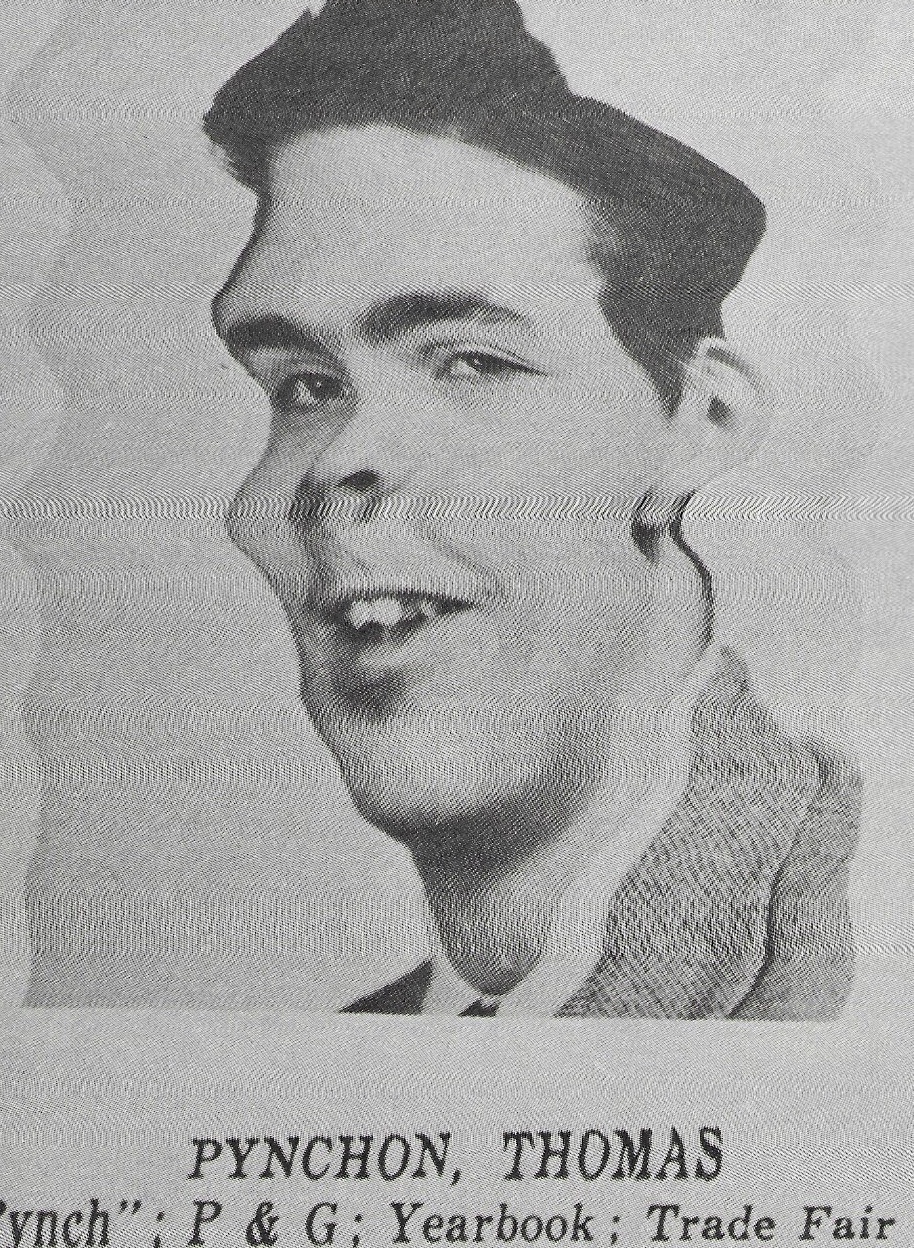

Thomas Pynchon sells his archive

The article notes that the “archive includes 48 boxes — 70 linear feet, in archivist-speak — of material dating from the late 1950s to the 2020s” and includes :typescripts and drafts of all his published books” to date as well as “copious research notes on the many, many subjects (World War II rocketry, postal history, 18th-century surveying) touched on in his encyclopedic novels.” And while the documents include letters related to publishing, it includes “no private letters or other personal material” — and no photographs of Pynchon.

The article also claims that Pynchon’s son Jackson “is described as having ‘compiled and represented the archive.'” (The passive voice there is a bit cryptic, but I guess cryptic is Pynchonian, so.)

The article offers a number of quotes from Sandra Brooke, the director of Huntington Library, including the notion that “‘a really substantial portion of the archive’ would be available in Pynchon’s lifetime.”

I’d love to see that lifetime go on and on, and even offer up a new novel.

“Not His Best” — Joy Williams

“Not His Best”

by

Joy Williams

from 99 Stories of God

Franz Kafka once called his writing a form of prayer.

He also reprimanded the long-suffering Felice Bauer in a letter: “I did not say that writing ought to make everything clearer, but instead makes everything worse; what I said was that writing makes everything clearer and worse.”

He frequently fretted that he was not a human being and that what he bore on his body was not a human head. Once he dreamt that as he lay in bed, he began to jump out the open window continuously at quarter-hour intervals.

“Then trains came and one after another they ran over my body, outstretched on the tracks, deepening and widening the two cuts in my neck and legs.”

I didn’t give him that one, the Lord said.

NOT HIS BEST