Maggie Umber calls the nine pieces collected in Chrysanthemum Under the Waves “comics,” so I will call them comics too. The term “comics” has long encompassed a wide range of visual storytelling techniques, resisting attempts to confine it to rigid structures, and Chrysanthemum Under the Waves shows the form’s expansive potential, blending horror, surrealism, and poetic fragmentation to tap into the alienation, paranoia, and repression that lurks under the surface of everyday life.

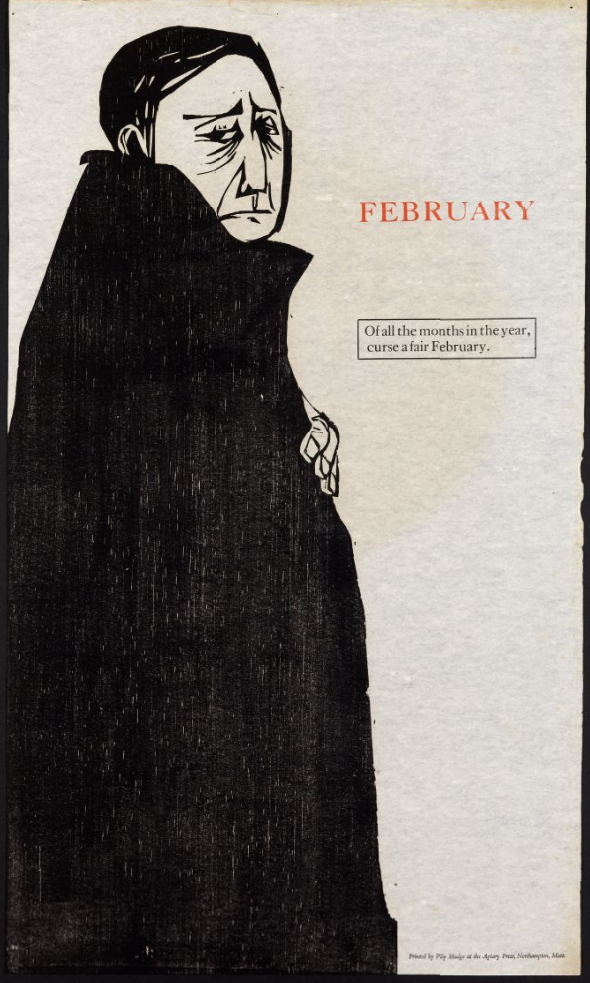

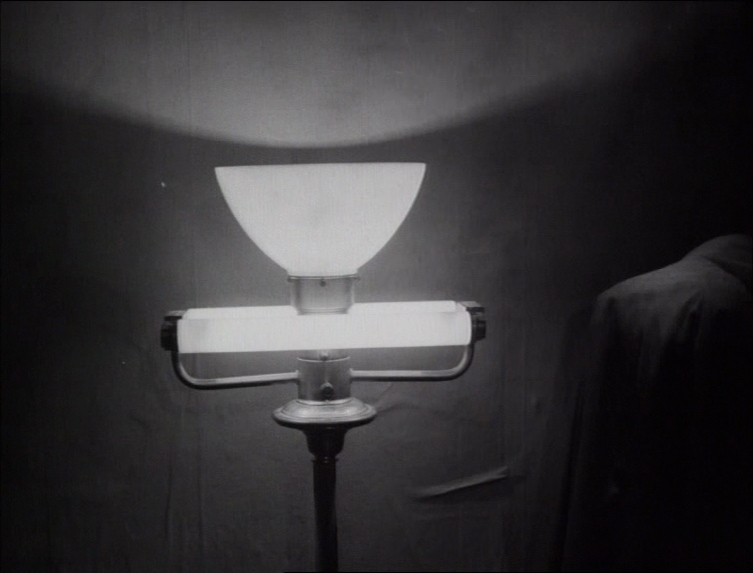

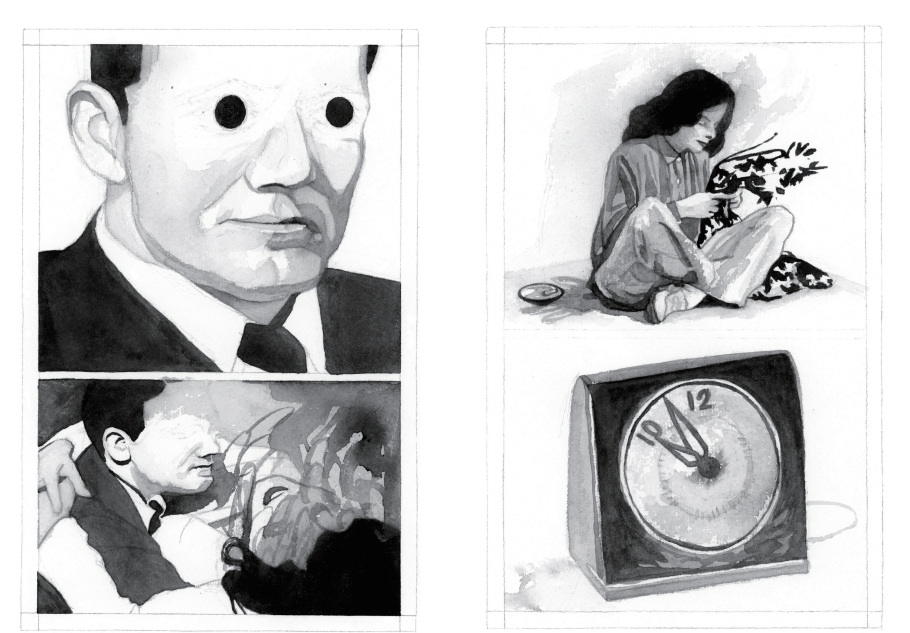

The stories here resist conventional narrative logic, which will likely confound any reader expecting something traditional. Umber eschews the common building blocks of the medium: there are no speech bubbles, no thought balloons, no panels stacking up into a coherent sequence. In fact, the few pages that use multiple panels feel like an anomaly. Most of the work in Chrysanthemum is confined to single, expansive images. Yet, these full-page spreads do not recall the bombastic splash pages of Jack Kirby or other Golden Age comics. Instead, they underscore the inherent incompleteness of storytelling. No artwork, no story, can ever present a full picture of reality—there are always gaps, always gutters. And in these gaps, dread and unease fester.

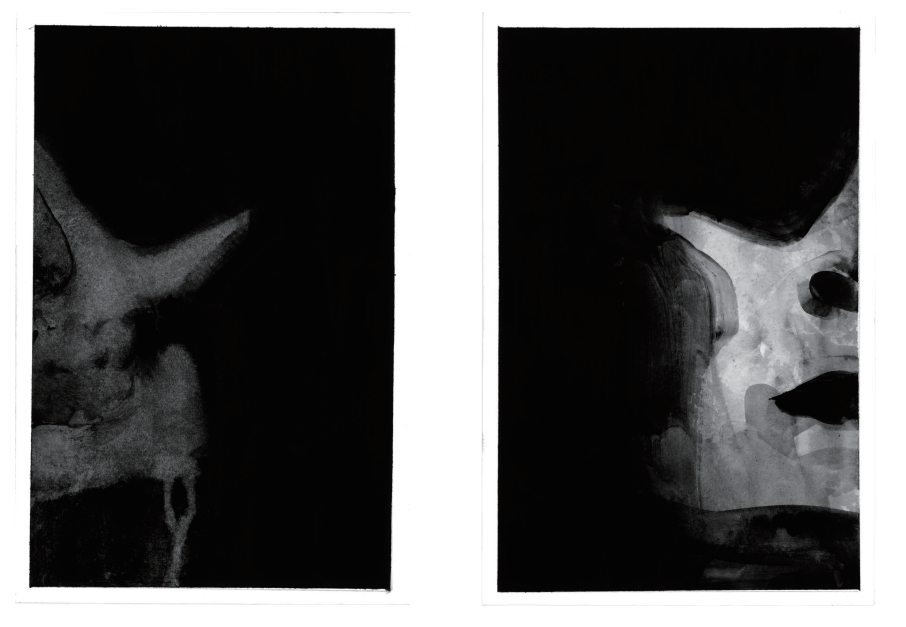

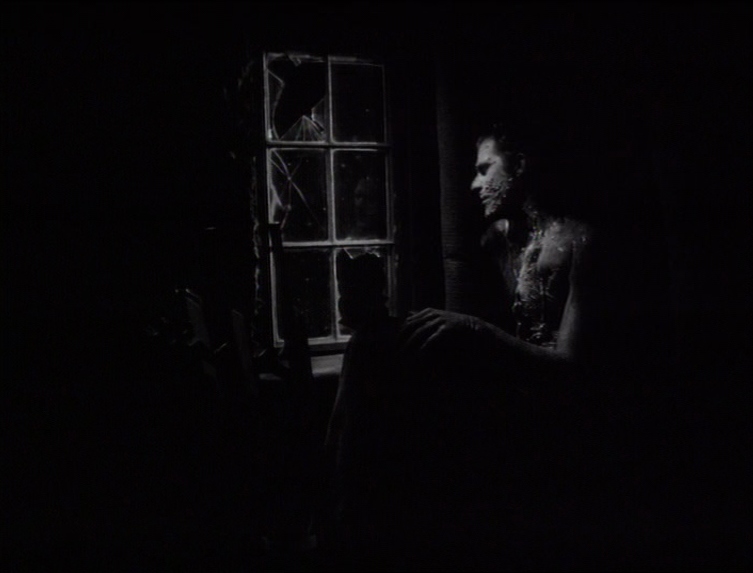

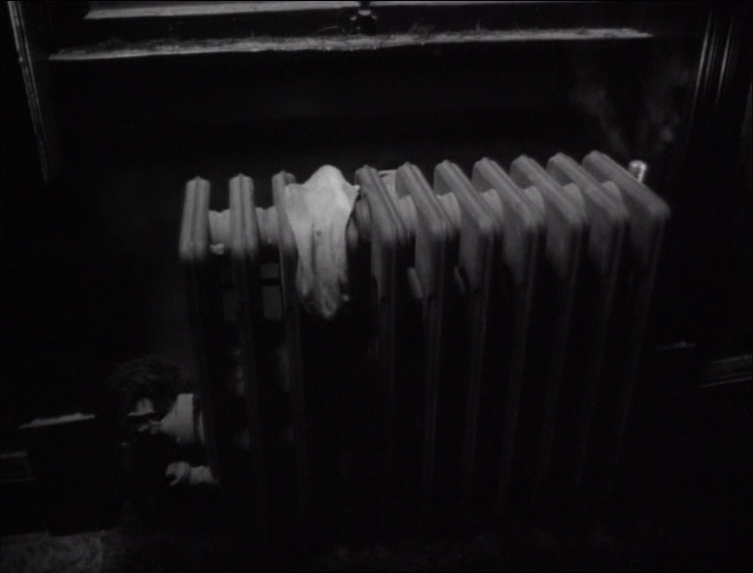

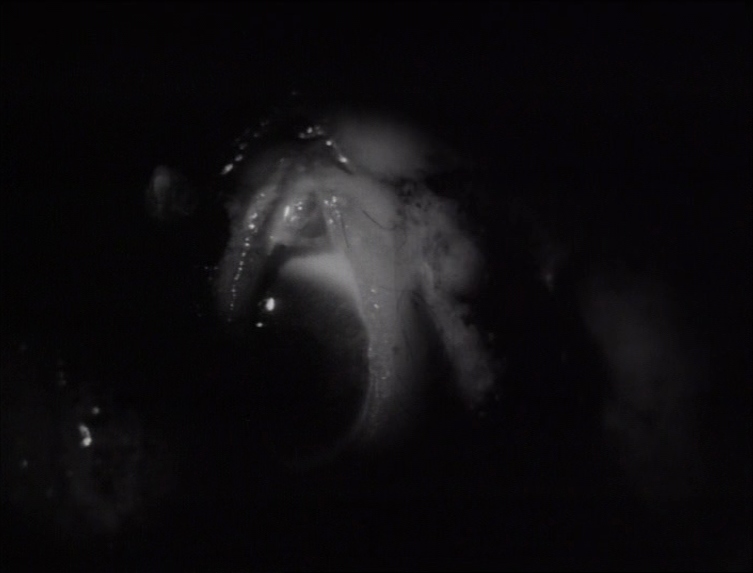

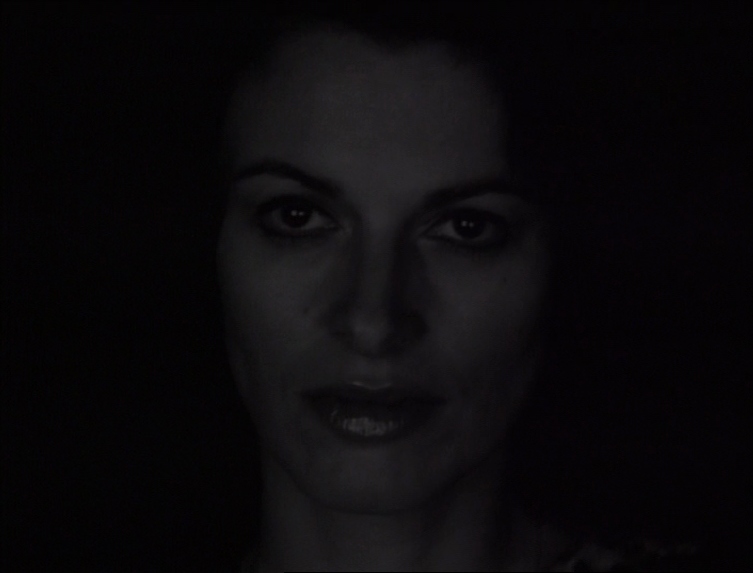

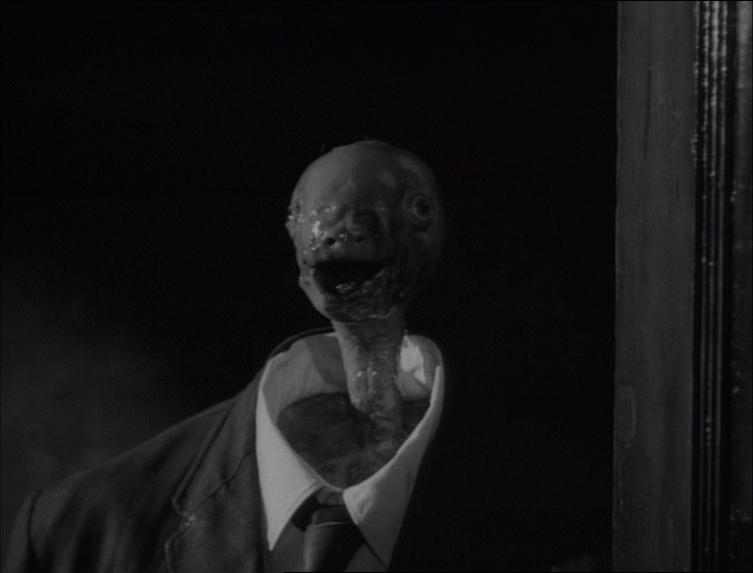

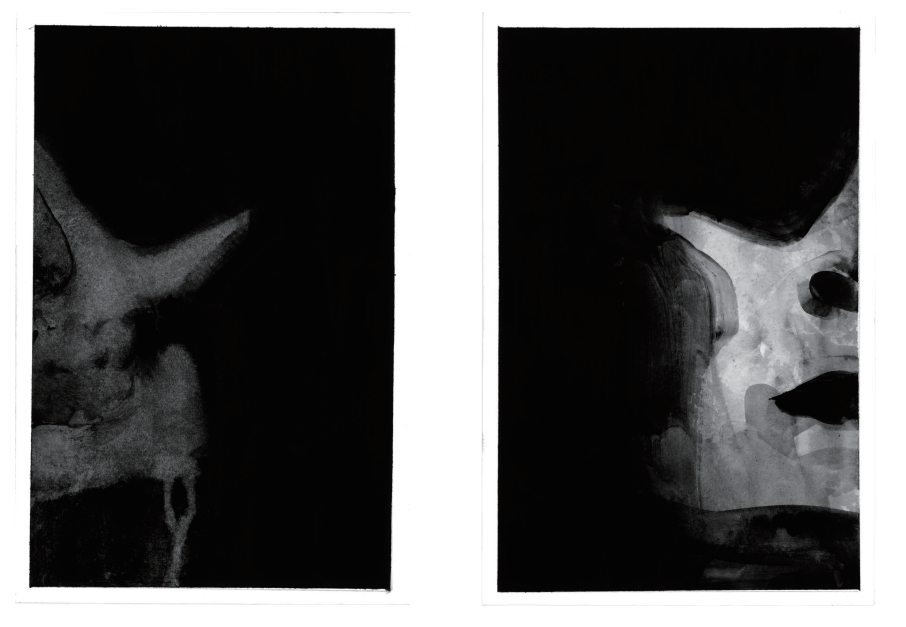

Umber’s comics aren’t so much about exploring the fragmentation of storytelling; rather, they showcase it as an aesthetic choice. It’s a choice that generates a palpable tension, a constant refusal to return to any resolution. There is no resolving tonic chord here. The uncanny permeates these pages—not in the sense of something foreign intruding upon the familiar, but as if the familiar itself has been subtly warped. Maybe this horror is “real,” maybe it’s not—but what is certain is its presence. The world Umber paints is one of perpetual strangeness, captured in black-and-white, shaded with grays. Pen and ink, printmaking, and watercolor all blur together in a form that makes us feel the unease before we can even articulate it.

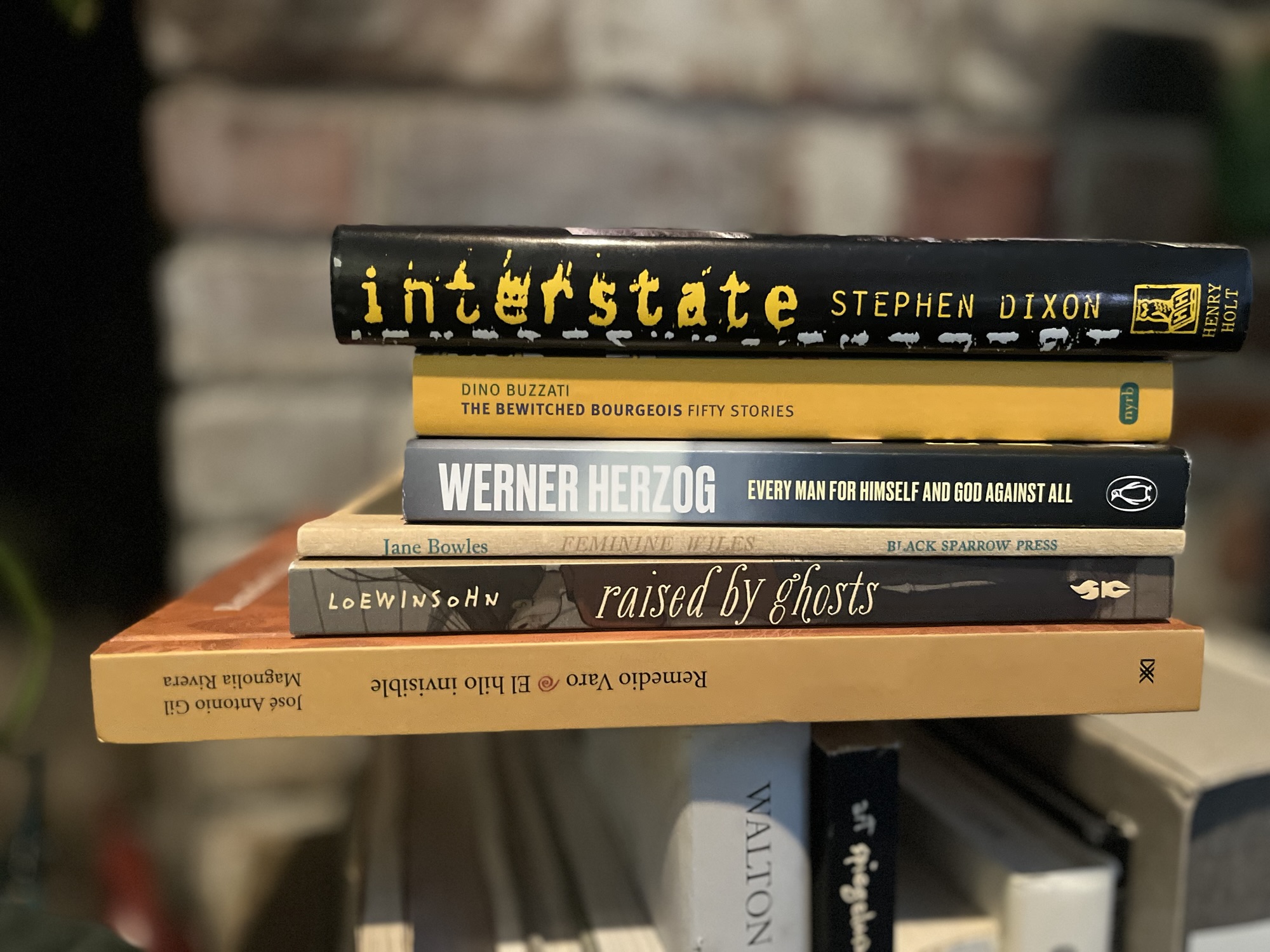

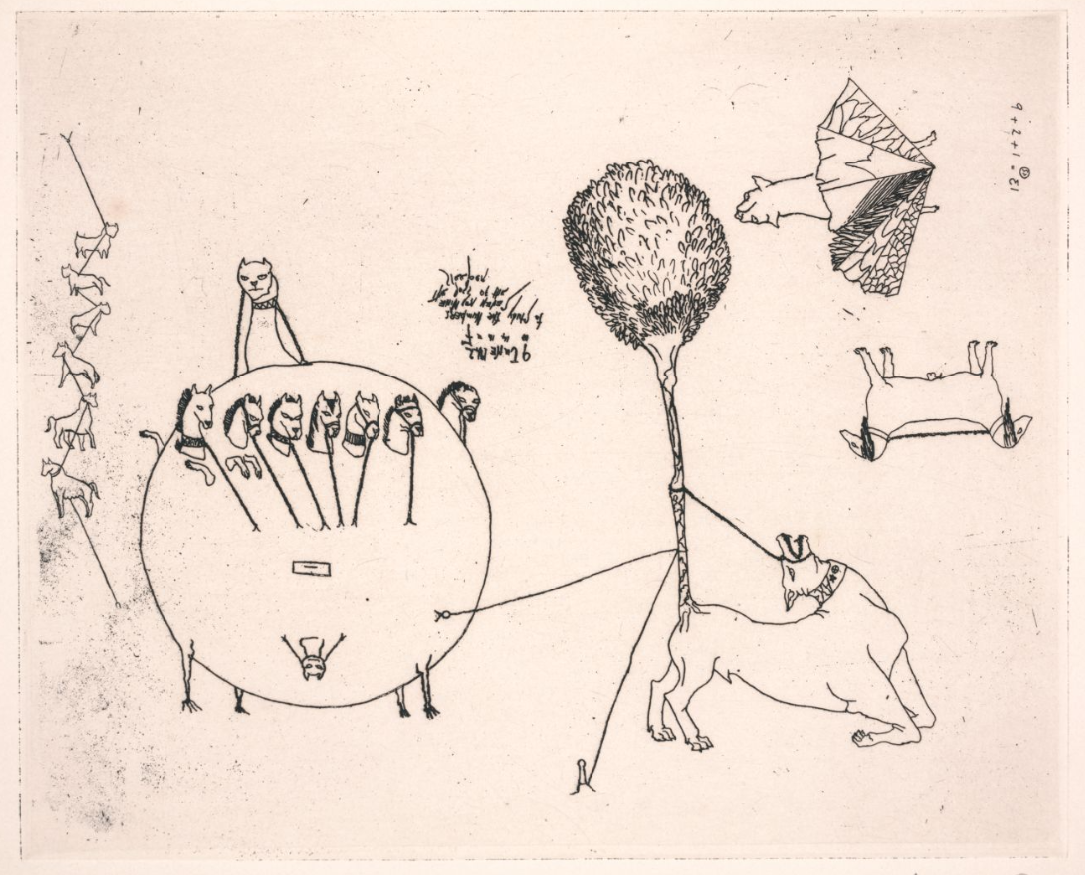

And while Umber’s work is refreshing in its uniqueness, it is by no means sui generis, but rather part of a clear tradition. As Umber notes in her introduction, Chrysanthemum started as a one-off “adaptation” of Shirley Jackson’s 1949 story “The Tooth.” If you have read “The Tooth” (and if you haven’t, do yourself a favor and resolve that problem) — if you have read “The Tooth,” you will likely recognize the uncanny unease that permeates Chrysanthemum. In her intro, Umber identifies James Harris as the agent of this unease: “James Harris snuck up on me when I was distracted by other things.” James Harris is a strange character who wanders in and out of not only “The Tooth,” but several of the other stories in Jackson’s The Lottery. Indeed, the original subtitle of The Lottery was not and Other Stories, but rather The Adventures of James Harris. This is the James Harris of the 17th century ballad “The Daemon Lover”; he is also the oblique star of Chrysanthemum Under the Waves. Look and you will find him in each of Umber’s tales, sliding like a shadow in and out of panels and gaps.

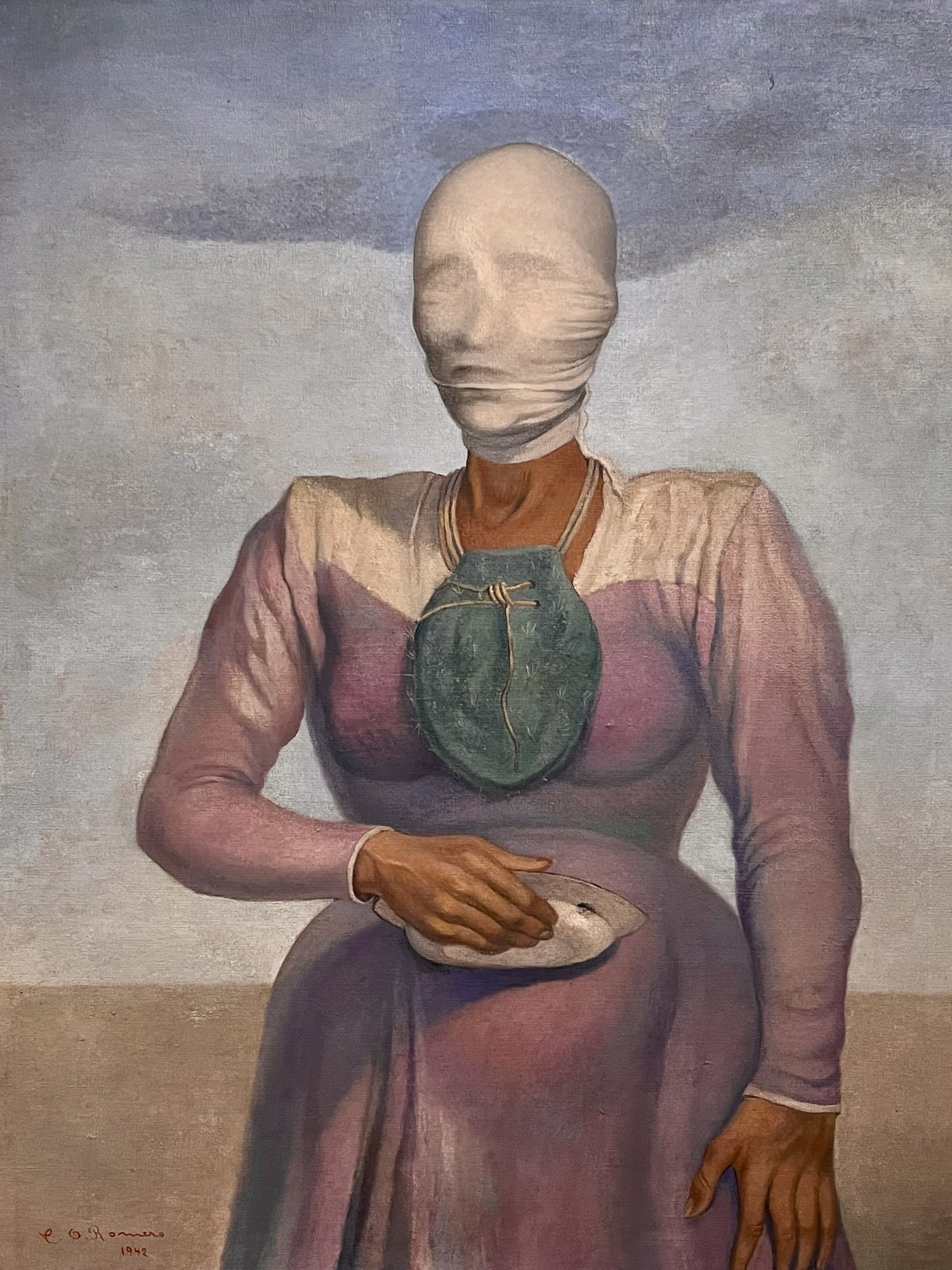

You will find so much more there as well–there are direct allusions to Goya’s Caprichos and Black Paintings, as well as nods to Toulouse-Lautrec and Sylvia Plath. There’s also a strong echo of Jackson’s American Gothic precursors and successors: Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, David Lynch, Kathy Acker — and, far less famously, Jason Schwartz. Chrysanthemum Under the Waves most reminded me of Schwartz’s prose-poem John the Posthumous, so much so that I read it again to confirm my notion.

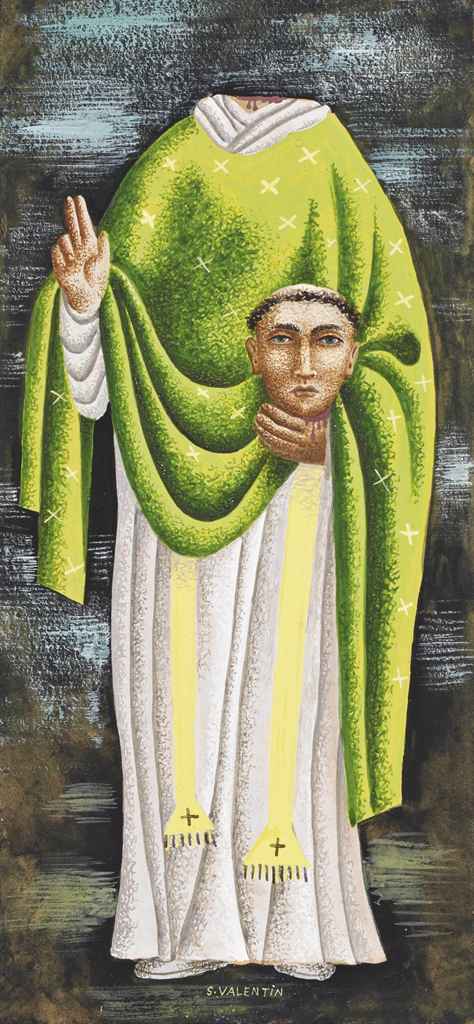

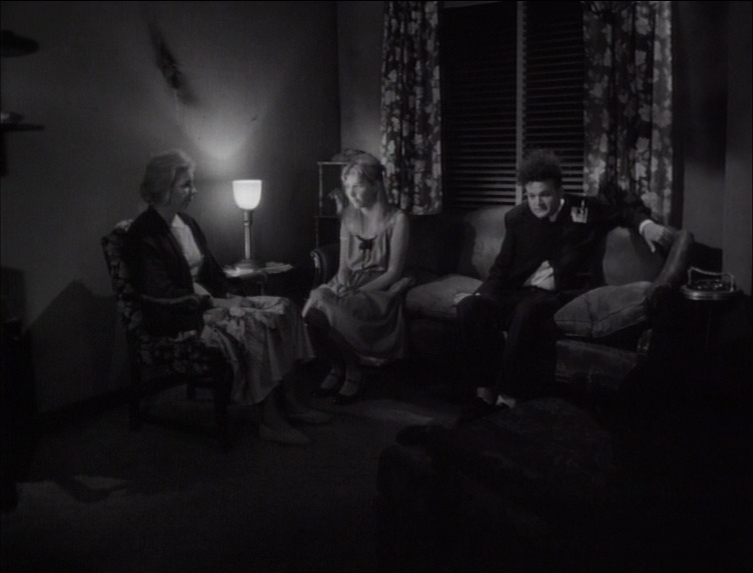

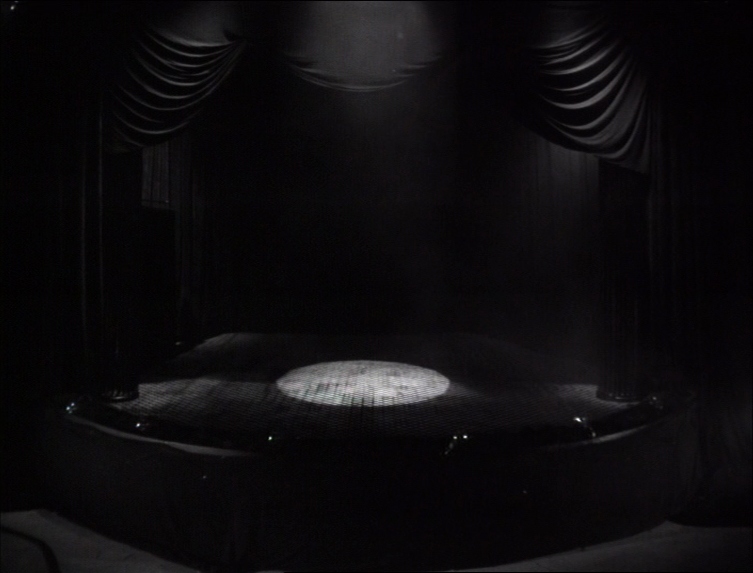

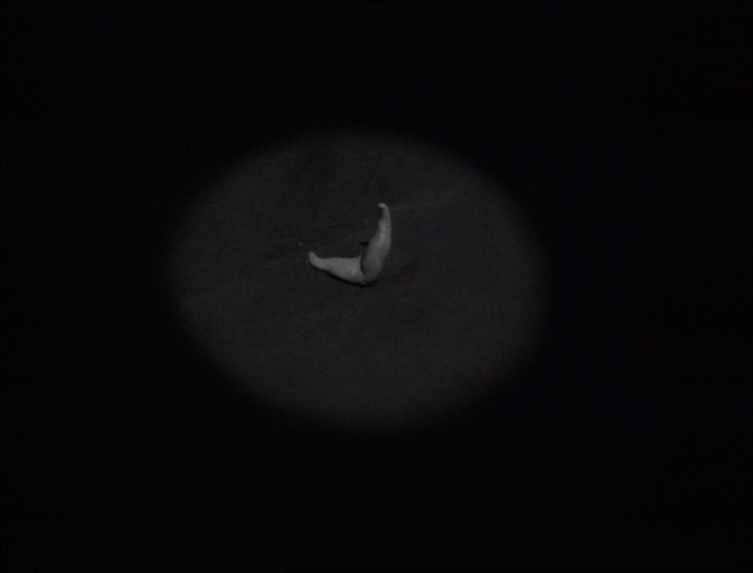

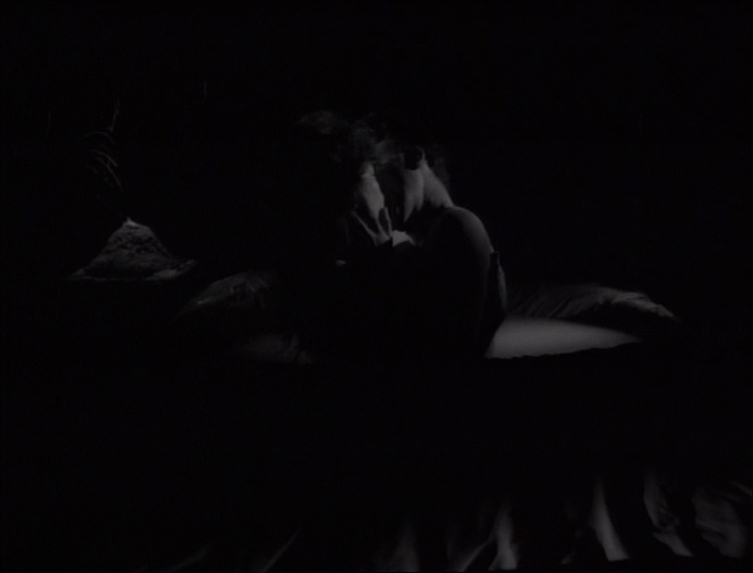

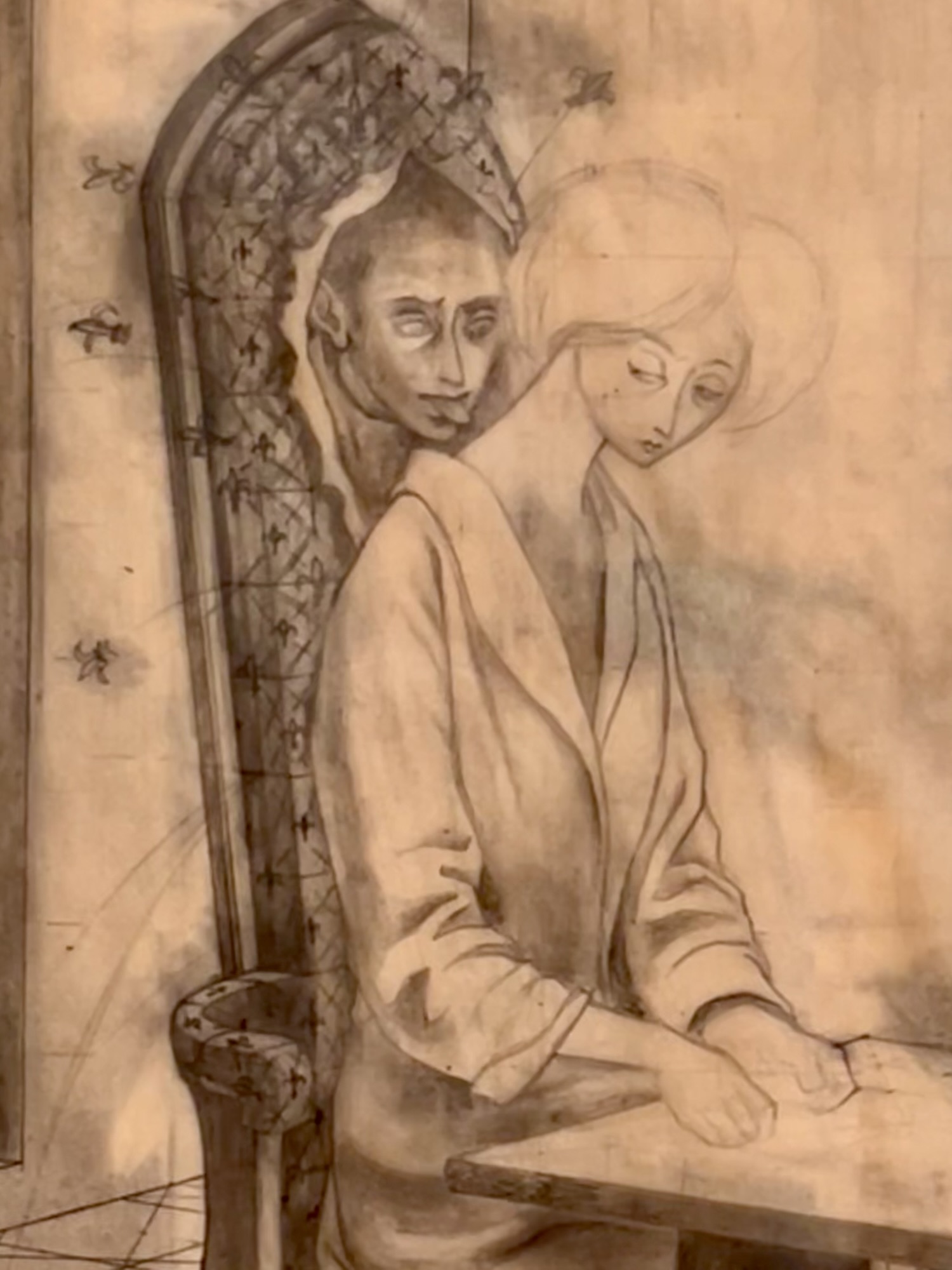

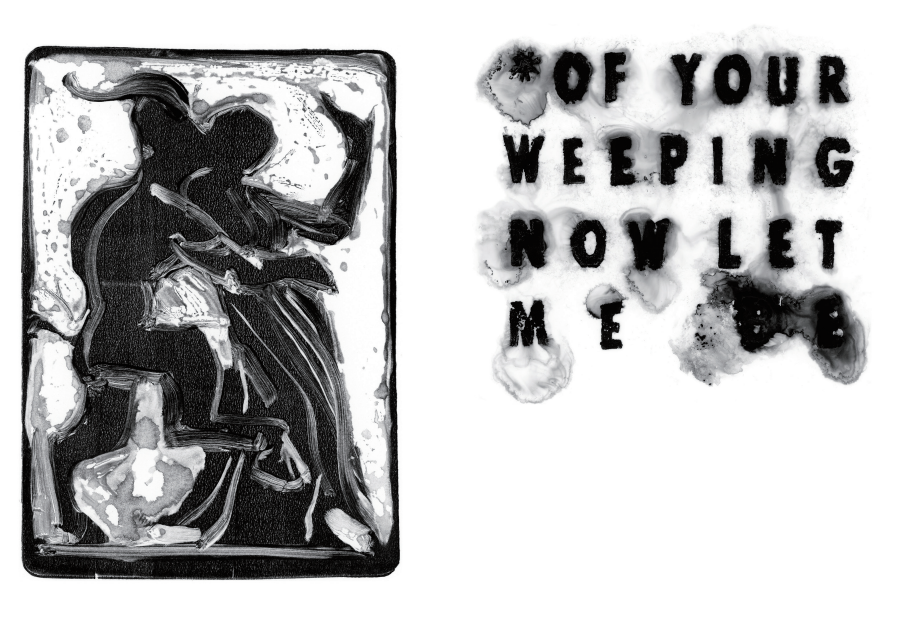

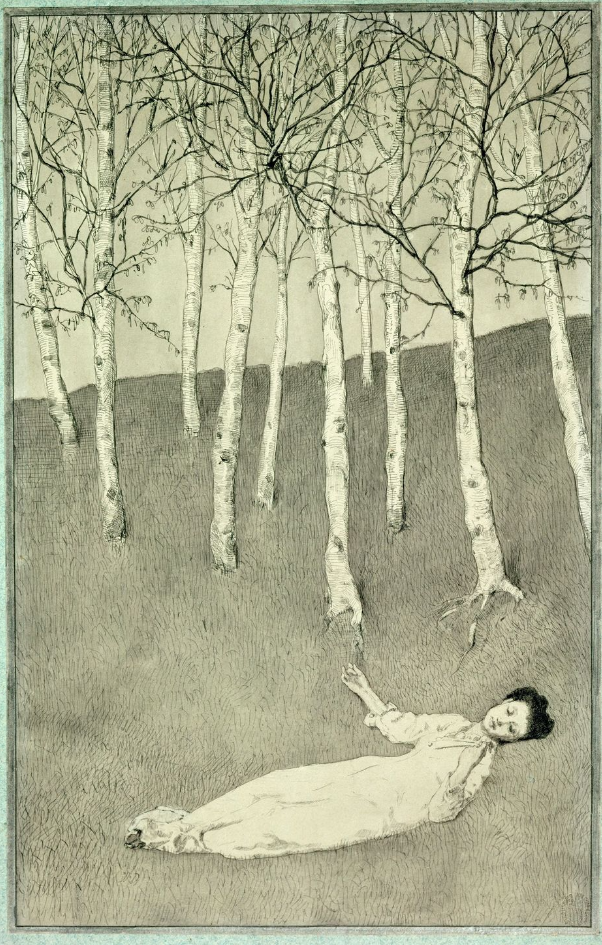

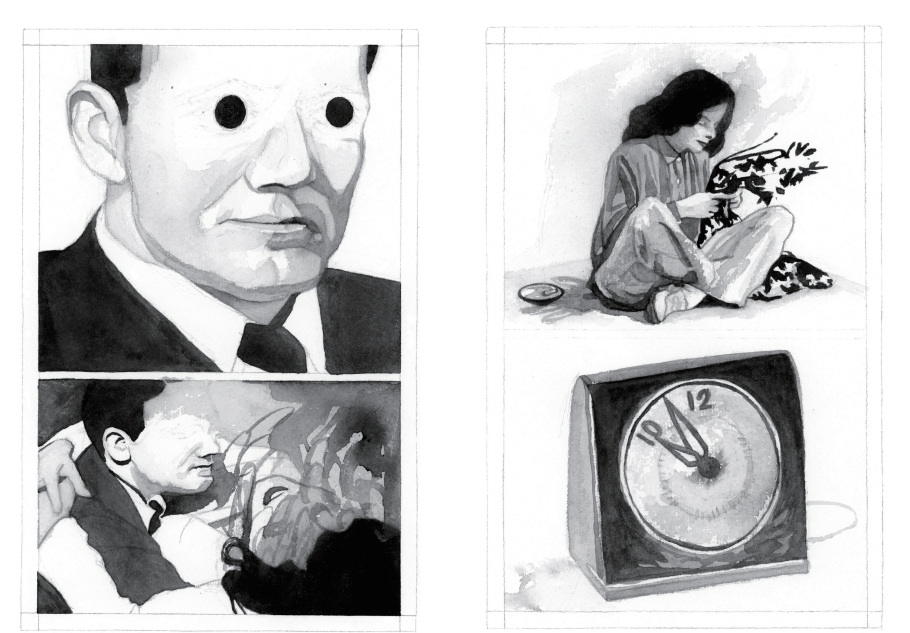

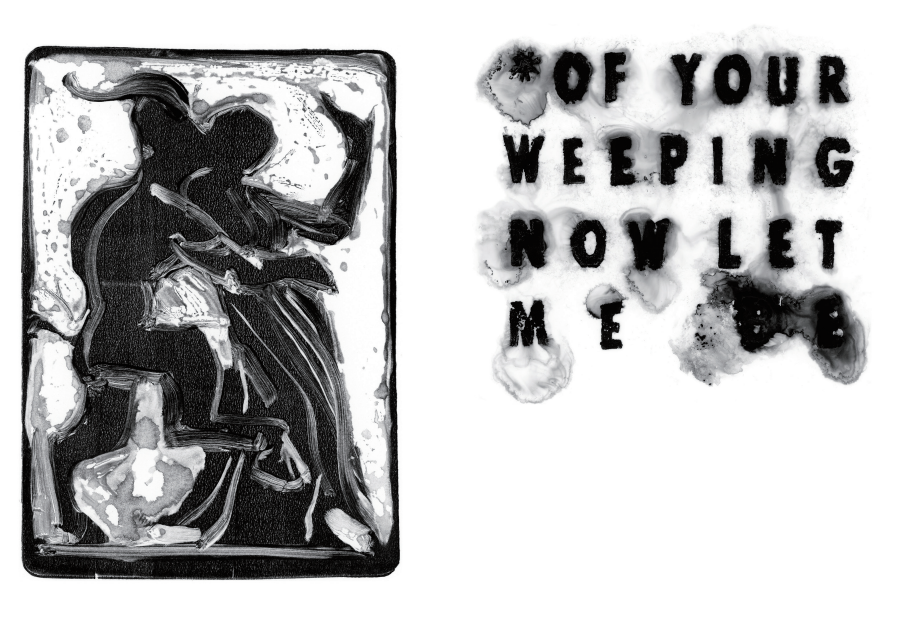

I’ve failed to remark so far on the apparent plots of the tales here. I found myself arrested by the ominous vibes in my first readings, and I still could not pin down a summary. At the same time, I feel that Umber clearly knows “what’s happening” in her stories, even if she keeps that information in the gaps and margins, out of the panel, but still, maybe, hidden in the pictures. The lead story, “Those Fucking Eyes,” is a collision of horror and beauty, twisting the artist’s gaze into something self-possessed and austere. “Rine” plays with fragmentation and distortion while evoking a ghostly presence. We get a gentleman caller, a broken bridge, a bouquet of flowers that flickers between reality and illusion. “Intoxicated” takes on a Gothic Toulouse-Lautrec aesthetic, unraveling into surreal rage and rejection. “The Devil Is a Hell of a Dancer” retells the “James Harris” ballad; it’s the first time written language infiltrates one of the stories.

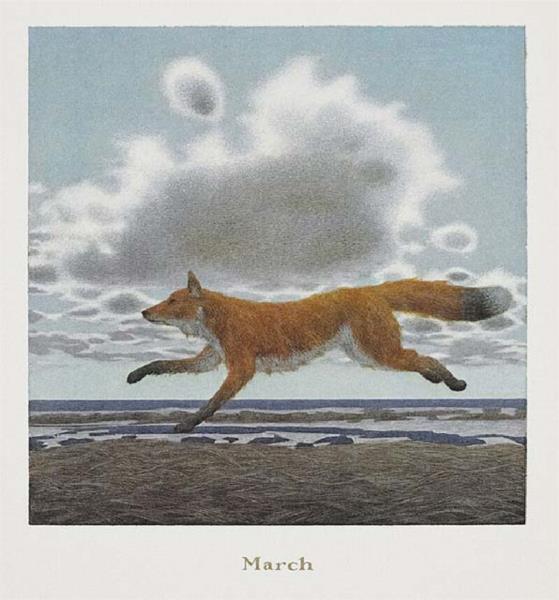

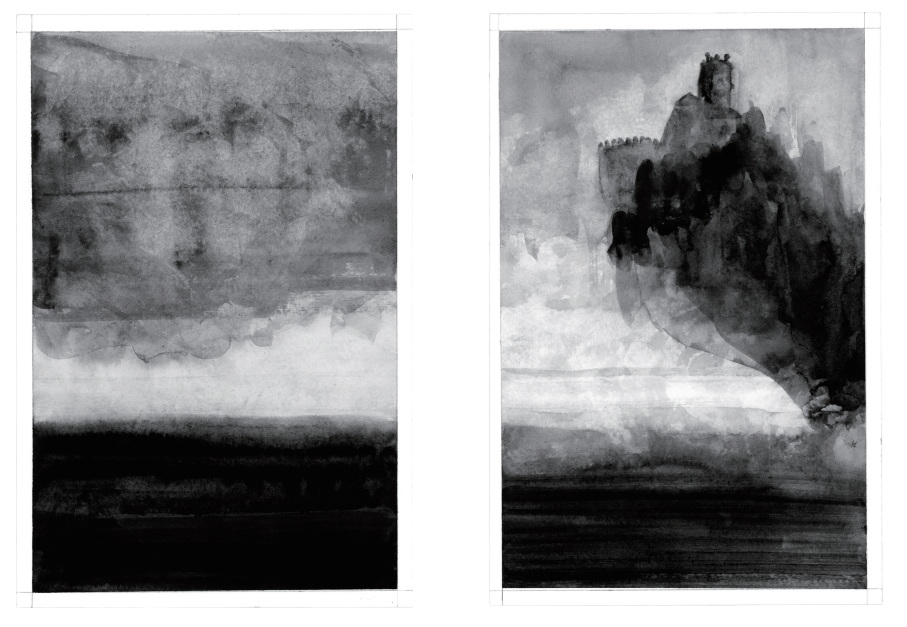

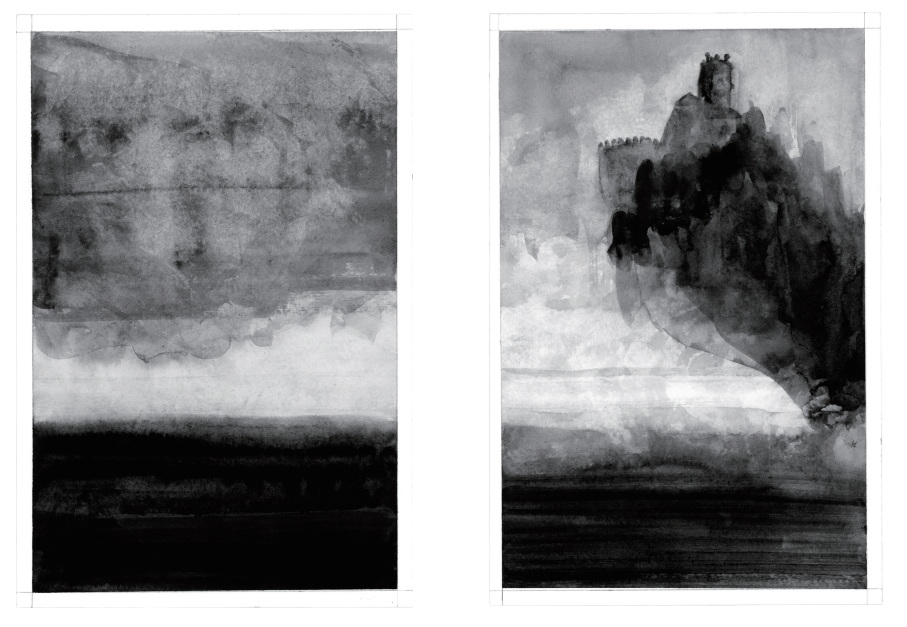

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s suffocating 1892 classic, “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” The shortest comic, “There Is Water” unfolds like a koan, enigmatic and meditative. Standout “The Witch” returns to Goya but also channels the American Gothic vein. The piece might be a nightmare one of Hawthorne’s characters endures. There are clouds, castles, dreams, doors, flickering horror. Is that a witch burning? And do the flames morph into a glimpse of Goya’s Saturn, only to resolve into the shadowed face of a woman? Shadows and erasures pulse through the imagery. It is both the strongest and longest piece in the collection. The book ends with “The Rock,” another riff on the the ballad “James Harris.” It’s a fitting end, conclusive but elusive. What remains rattles: unsettled, open, and always strange.

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s suffocating 1892 classic, “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” The shortest comic, “There Is Water” unfolds like a koan, enigmatic and meditative. Standout “The Witch” returns to Goya but also channels the American Gothic vein. The piece might be a nightmare one of Hawthorne’s characters endures. There are clouds, castles, dreams, doors, flickering horror. Is that a witch burning? And do the flames morph into a glimpse of Goya’s Saturn, only to resolve into the shadowed face of a woman? Shadows and erasures pulse through the imagery. It is both the strongest and longest piece in the collection. The book ends with “The Rock,” another riff on the the ballad “James Harris.” It’s a fitting end, conclusive but elusive. What remains rattles: unsettled, open, and always strange.

Chrysanthemum Under the Waves is a haunting, layered work that defies easy categorization. Umber’s pieces blend literary, artistic, and Gothic influences into a unique vision that expands the possibilities her chosen medium’s conventions. With its distinctive style and careful attention to space and detail, Chrysanthemum Under the Waves is a compelling read. Highly recommended.

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of