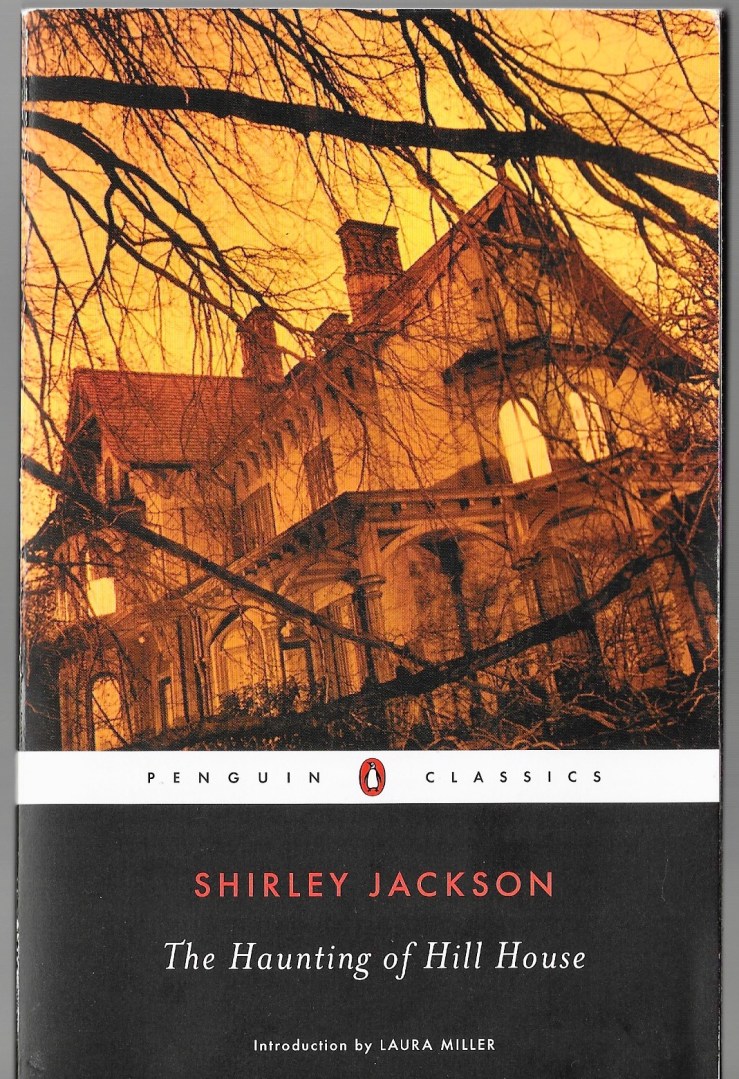

Nearing the end of Shirley Jackson’s 1959 American Gothic novel The Haunting of Hill House, and not having blogged that much in September of 2019, I thought that I’d write something about its perfect opening sentences, which I’ve returned to a few times (and used in my classroom).

Here are those opening lines:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against the hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

I shared the opening on twitter when I first read it the other week and one of the replies to the tweet linked to Random House copy editor (and author of Dreyer’s English) Benjamin Dreyer’s annotations of the first paragraph of The Haunting of Hill House. I didn’t read Dreyer’s annotations at the time, but as I sat down to write this blog, the memory that someone had already written about the opening of Hill House wormed its way into my soft brain. I read Dreyer’s appreciation twenty minutes ago, and then decided Not to Write this blog.

And then I decided to write anyway.

My fascination with the opening paragraph of Hill House has only increased as I’ve read the novel (the first I’ve read by Jackson, admittedly). When I first read the opening I was struck by Jackson’s forceful use of semicolons. There are three semicolons (and three periods) in the series of sentences, creating a strange stilted tilting rhythm.

Let’s consider the first sentence, comprised of two independent clauses:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.

Our novel begins with that magic word No. Phrases like “exist sanely” and “absolute reality” begin to sketch the novel’s themes. Jackson then pivots from the abstract to the concrete with her “larks and katydids”; in his annotations, Dreyer wonders “how many combinations of fauna Jackson experimented with before she landed on ‘larks and katydid.” I suspect those five wonderful syllables had lolled around her brain before the novel’s gestation.

And now our middle sentence, again two independent clauses tentatively joined by a semicolon:

Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against the hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more.

“Hill House, not sane” is a genius of four syllables, expressing again the theme of Jackson’s novel in terse curt prose. Dreyer finds fault with “the Hill/hills repetition right here,” writing that “it just doesn’t sing to me,” and suggesting that if he were the novel’s editor, he’d have “asked her whether she’d consider deleting ‘against the hills.'” That deletion would be a rhetorical mistake, I think, because the doubling of “hills” formalizes another of the novel’s tropes—twins and doubles, cousins and doppelgänger. Jackson’s punctuation instantiates this doubling in the first two sentences, both in the repetition of the semicolons and in the twinning of the phrases “by some” and “not sane.” (The repetition of “eighty years” serves as kind of syntactic echo, reverberating the ghostly theme from lifetime past to a generation beyond one’s own death.)

Here is the third and final line of the opening paragraph of Hill House, in which we get a rush of independent clauses—and another semicolon:

Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

The descriptions and events in the novel ultimately ironize this description: Hill House is hardly “upright,” nothing meets “neatly,” and the doors don’t seem to be “sensibly shut,” at least to the quartet of visitors who come to stay at Hill House. This quartet is led by and includes Dr. Montague a committed yet somewhat embarrassed paranormalist, who recruits three others: Luke Sanderson, heir to Hill House, wild Theodora (no last name), and Eleanor Vance, the viewpoint character who, cracked before the events of the novel begin, cracks even more.

(There is a part of me that would love to argue that the three opening sentences, sundered in strange twos by semicolons, represent Eleanor, Theodora, and Luke—but no, that’s ridiculous. Right?)

The final phrase of the last sentence, “walked alone,” set off by a comma (which Dreyer points out is unnecessary and perhaps ungrammatical) balances the other two-word nonessential elements (“by some” and “not sane”), highlighting its rhetorical importance. Hills is a novel of loneliness and companionship, of alienation and belonging. Our viewpoint character Eleanor navigates a walk alone in a world that may or may not be sane. And yet Eleanor doesn’t walk fully alone in this twisted house, with its infirm floors and unneat bricks and crooked walls. Hills vacillates between gloomy lethargy and kinetic ebullience, manically ping-ponging, thriving strangely, radiating a larky katydidiad dream of absolute unreality.