With Memorial Day ’11 just a memory and Labor Day warning off the wearing of white, I revisit some of the best books I read this summer:

Although I posted a review of Roberto Bolaño’s collection Between Parentheses two weeks before Memorial Day, I continued to read and reread the book over the entire summer. It was the gift that kept giving, a kind of blurry filter for the summer heat, a rambling literary dictionary for book thieves. For example, when I started Witold Gombrowicz’s Trans-Atlantyk a week or two ago, I spent a beer-soaked midnight tracing through Bolaño’s many notations on the Polish self-exile.

Trans-Atlantyk also goes on this list, or a sub-list of this list: great books that I’ve read, been reading (or in some cases, listened to/am listening to) but have not yet reviewed. I finished Trans-Atlantyk at two AM Sunday morning (surely the intellectual antidote to having watched twelve hours of college football that day) and it’s one of the strangest, most perplexing books I’ve ever read—and that’s saying something. Full review when I can process the book (or at least process the idea of processing the book).

I also read and absolutely loved Russell Hoban’s Kleinzeit, which is almost as bizarre as Trans-Atlantyk; like that novel (and Hoban’s cult classic Riddley Walker), Kleinzeit is written in its own idiom, an animist world where concepts like Death and Action and Hospital and even God become concrete characters. It’s funny and sad. Also funny and sad: Christopher Boucher’s How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive (new from Melville House). Like Trans-Atlantyk and Kleinzheit, Volkswagen is composed in its own language, a concrete surrealism full of mismatched metaphorical displacements. It’s a rare bird, an experimental novel with a great big heart. Full reviews forthcoming.

I’ll be running a review of Evelio Rosero’s new novel Good Offices this week, but I read it two sittings at the beginning of August and it certainly belongs on this list. It’s a compact and spirited satire of corruption in a Catholic church in Bogotá, unwinding almost like a stage play over the course of a few hours in one life-changing evening for a hunchback and his friends. Good stuff.

On the audiobook front, I’ve been working my way through George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series; I finished the first audiobook, A Game of Thrones, after enjoying the HBO series, and then moved into the second book, A Clash of Kings, which I’m only a few hours from completing. I think that the HBO series, which follows the first book fairly faithfully, is much closer to The Wire or Deadwood than it is to Peter Jackson’s Tolkien films—the story is less about fantasy and magic than it is about political intrigue during an ongoing civil war. This is a world where honor and chivalry, not to mention magic and dragons, have disappeared, replaced by Machiavellian cunning and schemers of every stripe. Martin slowly releases fantastic elements into this largely desacralized world, contesting his characters’ notions of order and meaning. There are also beheadings. Lots and lots of beheadings. The books are a contemporary English department’s wet dream, by the by. Martin’s epic concerns decentered authority; it critiques power as a constantly shifting set of differential relations lacking a magical centering force. He also tells his story through multiple viewpoints, eschewing the glowing third person omniscient lens that usually focuses on grand heroes in fantasy, and concentrates instead, via a sharp free indirect style, on protagonists who have been relegated to the margins of heroism: a dwarf, a cripple, a bastard, a mother trying to hold her family together, a teenage exile . . . good stuff.

Leo Tolstoy’s final work Hadji Murad also depicts a world of shifting power, civil war, unstable alliances, and beheadings (although not as many as in Martin’s books). Hadji Murad tells the story of the real-life Caucasian Avar general Hadji Murad who fought under Imam Shamil, the leader of the Muslim tribes of the Northern Caucuses; Shamil was Russia’s greatest foe. This novel concerns Murad’s attempt to defect to the Russians and save his family, which Shamil has captured. The book is a richly detailed and surprisingly funny critique of power and violence.

William Faulkner’s Light in August might be the best book I read this summer; it’s certainly the sweatiest, headiest, and grossest, filled with all sorts of vile abjection and hatred. Faulkner’s writing is thick, archaeological even, plowing through layers of Southern sediment to dig up and reanimate old corpses. The book is somehow both nauseating and vital. Not a pleasant read, to be honest, but one that sticks with you—sticks in you even—long after the last page.

Although David Foster Wallace’s posthumous novel The Pale King was released in the spring, I didn’t start reading it until June; too much buzz in my ears. If you’ve avoided reading it so far because of the hype, fair enough—but don’t neglect it completely. It’s a beautiful, frustrating, and extremely rewarding read.

Speaking of fragments from dead writers: part two of Roberto Bolaño’s The Third Reich, published in the summer issue of The Paris Review, was a perfect treat over the July 4th weekend. I’m enjoying the suspense of a serialized novel far more than I would have imagined.

Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation is probably the funniest, wisest, and most moving work of cultural studies I’ve ever read. Unlike many of the tomes that clutter academia, Humiliation is accessible, humorous, and loving, a work of philosophical inquiry that also functions as cultural memoir. Despite its subject of pain and abjection, it repeatedly offers solutions when it can, and consolation and sympathy when it cannot.

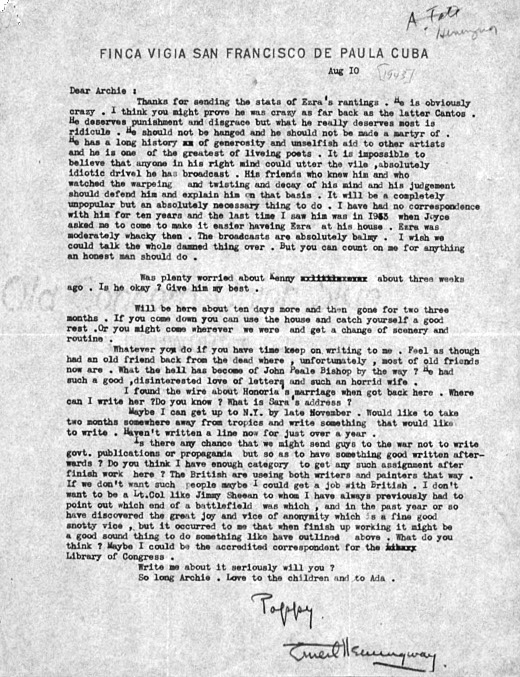

So the second posthumously published, unfinished novel from a suicide I read this summer was Ernest Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden, the sultry strange tale of a doomed ménage à trois. (I’m as humiliated by that last phrase as you might be, dear reader. Sorry). Hemingway’s story of young beautiful newlyweds drinking and screwing and eating their way across the French Riviera is probably the weirdest thing he ever wrote. It’s a story of gender reversals, the problems of a three-way marriage, elephant hunting, bizarre haircuts, and heavy, heavy drinking. The Garden of Eden is perhaps Hemingway at his most self-critical; it’s a study in how Hemingway writes (his protagonist and stand-in is a rising author) that also actively critiques his shortcomings (as both author and human). The Garden of Eden should not be overlooked when working through Hemingway’s oeuvre. I’d love to see a critical edition with the full text someday (the novel that Scribner published pared down Hemingway’s unfinished manuscript to about a third of its size).

Also fragmentary fun: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Notebooks. Like Twitter before Twitter, sort of.

These weren’t the only books I read this summer but they were the best.