“Fiction” by Carl Shuker

So there was a US novelist, permanently relocated to the UK some years back for an MFA, now mid-list, mid-career and “between books”, thirty-mid-something, author of two well-received novels and a less-well-received book of short stories, product of a labor of ten years on and off, and thus at the quintessential time and place to stall, creatively, who was that kind of writer who worked from emotion thence into intellect and, if he was successful, back once again into emotion, “evoked.“

And he came to the Lebanon looking to be bitten by the dragonfly.

Emotion > intellect > emotion. From the dream to the text to the dream. In practice this meant the not-so-youngish writer knew his subject when it hurt his heart, when it obsessed him and seemed too painful and the hardest thing at which to look. Then the writer knew he would have the dark, acidic energy it took to compose, edit, destroy, recompose, re-edit, polish and eventually finish, after years, a novel something like the kind of novels he loved and aspired to create, the books that made him want to become a writer in the first place. This method, which he fell into rather than chose, in the messy process of finding one’s way as a writer in his twenties, meant that by his early thirties the writer had published first one deliberately thinly veiled book of first-person late-adolescent horror, which counted, for its relative success, on the frisson of a patchwork of à clef-ish links with his own life and on making his own weaknesses—inexperience and naiveté—part of the material, and had published second one semi-immense “follow-up” or “sophomore effort”, as critics who hadn’t read the first book always wrote, a terrific shambling thing that during the long three years of its composition veered in his imagination from being a bloated, confused, constant evasion of a real book, a shadow of the kind of book it aspired to be, to being sometimes briefly the most amazing thing he’d ever read, like, ever; structured, strong, urgent, inevitable; the writer being thrilled and dazzled it’d come out of himself, then brutally depressed and miserable at its derivativeness and the puniness of his talent and by extension his soul, his self. And so how he’d done it (coming back to the MO thing), how he’d surmounted the hugeness and endlessness of the task and this bipolar crippling self-doubt and corresponding occasional massively inflated sense of self-importance was with the choice of a subject so tough, so big and hard, so new, that he had a kind of duty to it; a duty that transcended his own comfort and his own ego. A duty to the world. A subject that humbled and steeled. The second book was published to polite notices but bigger papers and a year or so of peace for the writer, and then the award of a one-year fellowship slash residency at a red-brick university like the one he’d graduated from (in crea writ, natch; the MFA) wherein the writer was immediately expected to write again. Having drawn on his childhood and his adolescence, having spent most of his twenties writing or thinking about writing while not publishing anything, the writer was immediately wary of being seen, by imagined peers, by his remembered brutal adolescent reading self with its impossible but definitive demands, of having sold out or trying to be commercially big, not cool or hard or true or essential, so he carved out a book of singular and odd semifuturistic short stories and a novella that linked them all, in a hazy darkness of second-novel-hangover and fellowship-paid-for Scotch, a clutch of one-night-stands compared to the love affairs of the first books, and worked really hard while never really, really loving these new small strange things, never adoring them like he did the books he’d had to summon forth forces for that were old and presymbolic and frightening. He had an office and stuff, and people knew he was a writer. This hadn’t happened before.

And then he got a job teaching creative writing.

Continue reading “Read “Fiction,” a Short Story by Carl Shuker” →

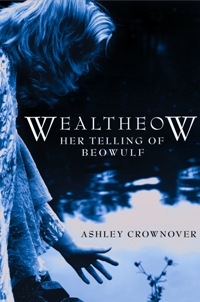

In her novel Wealtheow, author Ashley Crownover retells Beowulf from Queen Wealtheow’s point of view. In the original epic poem, Wealtheow doesn’t have much of a voice. Her marriage to King Hrothgar is more a matter of politics than love, and her role in the poem is largely limited to an episode where she speaks up to secure her own genealogical futurity. Adopting a first-person voice, Crownover portrays Wealtheow as a young, somewhat naive bride thrown into a political marriage arranged to prevent war between the Danes and the Helmings. Wealtheow tries to fit into her new role as wife and queen, as well as her new culture, and strives to produce an heir for Hrothgar, suffering miscarriages and other adversities. Crownover parallels Wealthow’s plighted road to motherhood in the tale of Grendel and his mother (called Ginnar here). When Grendel is born deformed, his father rejects him and he is bound for infanticide–only Ginnar’s motherly instinct resists custom, and the pair become fugitives. Crownover’s technique here builds sympathy for Ginnar in echoing the narrative proper of Wealtheow. Ginnar in many ways is a far more sympathetic (and interesting) character than Wealtheow, and the counter-plot of her and her monster-spawn/beloved boy Grendel is the highlight of the book.

In her novel Wealtheow, author Ashley Crownover retells Beowulf from Queen Wealtheow’s point of view. In the original epic poem, Wealtheow doesn’t have much of a voice. Her marriage to King Hrothgar is more a matter of politics than love, and her role in the poem is largely limited to an episode where she speaks up to secure her own genealogical futurity. Adopting a first-person voice, Crownover portrays Wealtheow as a young, somewhat naive bride thrown into a political marriage arranged to prevent war between the Danes and the Helmings. Wealtheow tries to fit into her new role as wife and queen, as well as her new culture, and strives to produce an heir for Hrothgar, suffering miscarriages and other adversities. Crownover parallels Wealthow’s plighted road to motherhood in the tale of Grendel and his mother (called Ginnar here). When Grendel is born deformed, his father rejects him and he is bound for infanticide–only Ginnar’s motherly instinct resists custom, and the pair become fugitives. Crownover’s technique here builds sympathy for Ginnar in echoing the narrative proper of Wealtheow. Ginnar in many ways is a far more sympathetic (and interesting) character than Wealtheow, and the counter-plot of her and her monster-spawn/beloved boy Grendel is the highlight of the book.