Toward the end of the 130 page monologue that is Roberto Bolaño’s novella By Night in Chile, narrator Father Sebastián Urrutia Lacroix claims that “An individual is no match for history.” His statement neatly encapsulates (what might be) the dominant theme of By Night in Chile, namely an individual person’s capacity and ability to correctly–and sanely–somehow measure, attest to, confront, and witness the horror and brutality of history. In this case, Bolaño’s narrator, a Catholic priest–and conservative literary critic (and, of course, failed poet)–Father Urrutia, via a sweeping deathbed confession of sorts, recounts his life story, leading inexorably to Pinochet’s coup and its attendant subsequent draconian reforms and abuses. While it would be a mistake to reduce Bolaño’s rich novella to one conflict, I think the root of Urrutia’s struggle emanates from his inability to come to terms with his role as an intellectual (let alone an artist, critic, or priest) complicit somehow in Pinochet’s crimes. Throughout the book, from the very beginning, Urrutia blames his inner turmoil on a “wizened youth” (I don’t want to spoil this antagonist’s identity, but puzzling out that paradoxical appellation provides a major clue), a kind of idealist who stands apart from the dying priest, mocking and taunting him. After his claim that “An individual is no match for history,” Urrutia avers that “The wizened youth has always been alone, and I have always been on history’s side.” For Urrutia, this is of paramount importance, not just as a Catholic priest (which, it must be pointed out, is a role he doesn’t seem particularly suited for) but also as a literary critic and intellectual: Urrutia wants to systematize and critique history, to be “on the right side of history,” to quote Barack Obama. And yet his own attempt to narrativize his own life ironizes and critiques this very possibility at every turn–he is a sham, a charlatan, motivated and prompted by fear and even hate.

And on that attempt to narrativize a life: I would call By Night in Chile an anti-bildungsroman. Although Urrutia relates a life story, the free flow of psychic impressions that characterizes his telling slip and sail and rock and crash throughout years and over decades, often flowing backwards and forwards, sometimes spending pages on what could only be considered inconsequential minutiae, while at times glossing over the profoundest events with little more than a word or two. It is often what Urrutia does not remark upon that characterizes what is of the greatest importance in this work, and this is a testament to the power of Bolaño’s writing, to his command of voice. In one of the greatest performances of the novel, Urrutia describes the time right before, during, and after Pinochet’s coup. The passage is less than four pages, and for every contemporary action of immediate consequence, Urrutia seems to provide twice as many examples of his retreat into the past: ” . . . the first anti-Allende march was organized, with people banging pots and pans, and I read Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides, all the tragedies, and Alkaios of Mytilene and Aesop and Hesiod and Herodotus . . . .” Urrutia doesn’t bother to scrutinize or analyze the visceral reality of history in the making around him, regressing instead to the comfort of established philosophical tradition–the history of Herodotus in favor of the chaos, anarchy, and brutality happening around him. He’s really quite a terrible priest, and as an intellectual he refuses to be engaged. Confident that he will always be “on history’s side,” he refuses to actively even try come to terms with history until he’s dying. And thus we get the narrative of By Night in Chile.

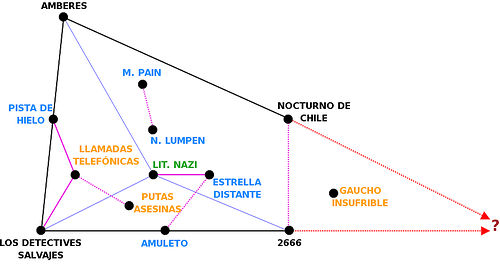

This reckoning with the past takes the form of a long monologue but, as those familiar with Bolaño will attest, there are plenty of other voices here, stories nested within stories like Russian dolls. The force and vitality of Urrutia’s speech is astonishing; one envisions the monologue as a single immediate and discrete exhalation, a stream of memory, the living wail of a dying man. Bolaño’s rhetorical style here conveys this ironic energy. He employs long (very, very long) sentences, sometimes going on for several pages, and often uses little or no transitions between what should be major shifts of space and time. There are plenty of references to writers, of course, many obscure, and more motifs and leitmotifs than I can work out here (or elsewhere, to be honest). I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest that the book is probably even more intense in the original Spanish, although I think Chris Andrews has done a brilliant job translating here, just as he did in Last Evenings on Earth. And since I’ve brought up that book, I’m going to make another suggestion: if you’ve yet to read Bolaño, you should, and Last Evenings of Earth (or 2666 if nearly a thousand pages doesn’t seem too daunting)is probably the best place to start–which is kind of another way of saying that By Night in Chile is not the best entry point to Bolaño–at least not for anyone intimately familiar with Latin American history. It’s not that By Night is particularly challenging or hard to read. However, I think that this particular book will probably be better enjoyed with more context. As Rodrigo Fresán points out in his essay “The Savage Detective,” (published in the March 2007 issue of The Believer), By Night in Chile could be (should be?) read as part of one cohesive book along with Amulet and Distant Star. Indeed, as many critics have pointed out, Bolaño’s works seem to coalesce into one great work, a secret universe parallel to Tolkien’s Middle Earth or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha. Urrutia’s voice enriches this universe, but one must have something of a foothold on Bolaño’s themes in order to appreciate the complex ironies of By Night in Chile. Or maybe not. Maybe this is a great entry point to Bolaño. Either way, great book. Highly recommended.

Editorial note: Biblioklept ran the original version of this review in July of 2010. I saw the new cover for By Night in Chile today in a bookstore I was visiting in a town that I do not live in, and the new cover—the picture of which is the only new “content” for this review—is the occasion for republishing this Bolaño review.