Okay. So obviously a list of the books I didn’t read in 2011 would be, y’know, long.

This post is about the books I set out to read, tried to read, wanted to read, abandoned, neglected, acquired and thought looked interesting, etc. It’s also about what I want to—what I plan to—read in 2012.

A reasonable starting place: I wrote a post in early January of this year detailing the books I would try to read in 2011. I actually read most of the books I named in that post. But:

I failed to read past page 366 of Adam Levin’s incredibly long novel The Instructions, although I think I was a bit too harsh in my semi-review. Chalk it up to exhaustion.

I failed to even begin to try to read William Gaddis’s incredibly long novel JR. (But I swear to read it one year. Not next year, but maybe the year after?).

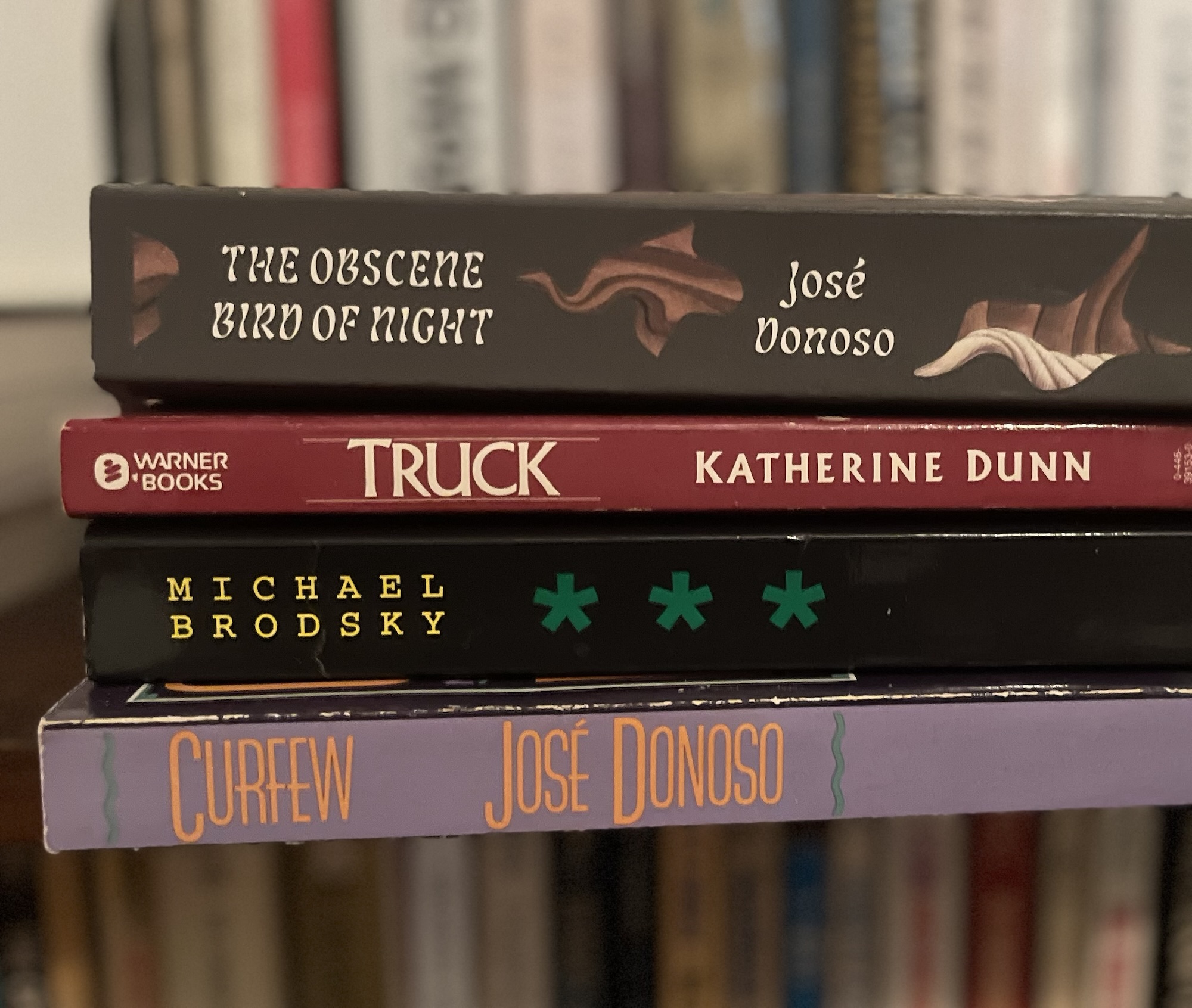

I failed to read past the first chapter of Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love.

I read most of the Tintin collections I picked up last year, but I didn’t get to volumes 5 or 6.

Moving beyond that early post, books that I recall abandoning (although I’m sure there must be more):

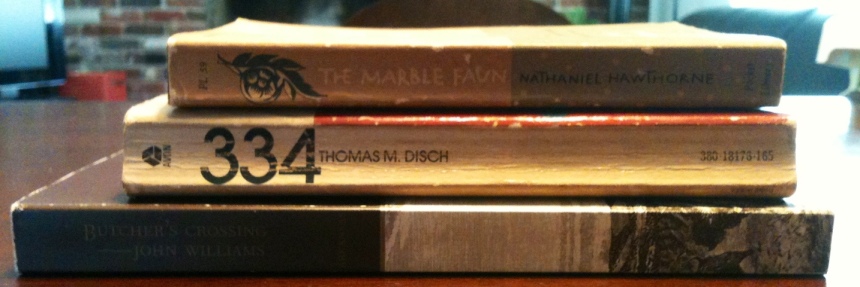

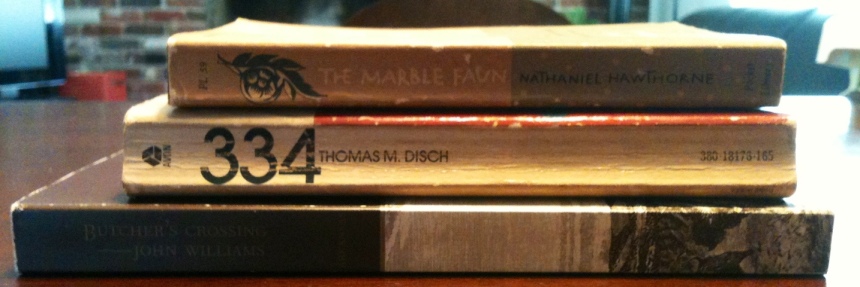

I abandoned Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Italian romance The Marble Faun after about 30 pages.

I abandoned 334 by Thomas Disch after about 50 pages. Somehow simultaneously dense and loose, it struck me as intensely imagined and sloppily composed.

I abandoned John Williams’s Butcher’s Crossing after the first chapter; it was a great opening chapter, but I thought it was going to be, I don’t know, more like Blood Meridian.

I also abandoned Chad Harbach’s big book The Art of Fielding (after 100 pages) because it was lame (notice it’s not pictured above because I traded in that sucker), but I had a nice dialog with some readers who responded to a post I wrote about abandoning it, so that was a plus.

Books I bought in 2011 that I aim to read in 2012:

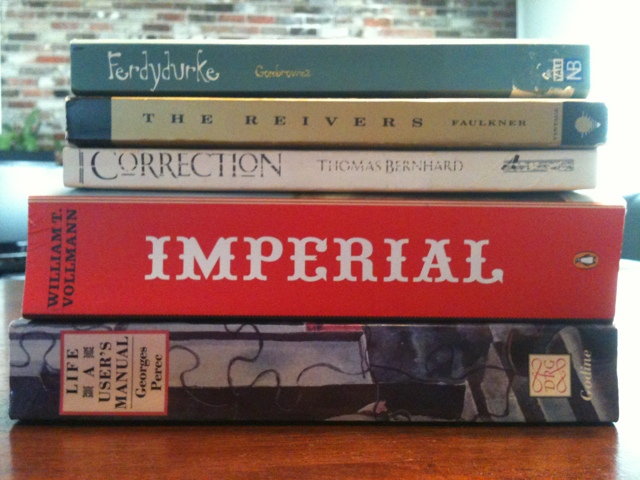

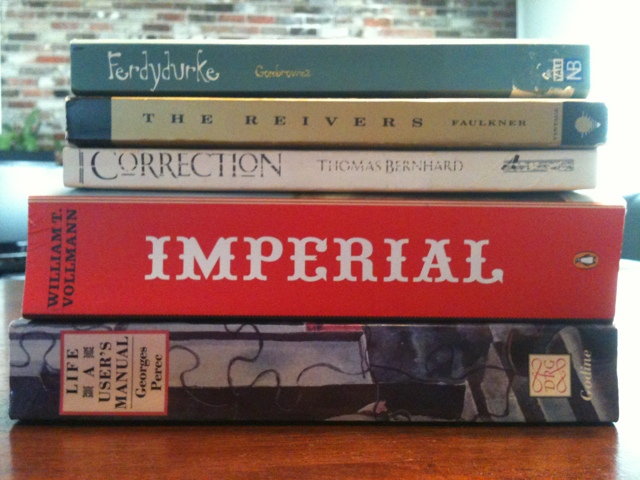

Correction by Thomas Bernhard. Bernhard was a repeated suggestion from readers in the aforementioned Harbach post/rant, and he was apparently a huge influence on W.G. Sebald, so, yes, looking forward to this.

The Reivers by William Faulkner. I read A Light in August this year and reread most of Go Down, Moses. My plan is to read one Faulkner a year for the next ten years.

Ferdydurke by Witold Gambrowicz. I struggled to make it through Gombrowicz’s bizarre jaunt Trans-Atlantyk, but once the novel taught me how to read it, I was enchanted by its strange humor and frenetic syntax. Over some beer and wine, I had a conversation about Ferdydurke with my father-in-law’s priest who is Polish. His pronunciation of Ferdydurke should win an award for charm.

I will read Georges Perec’s big book Life: A User’s Manual.

I have already promised to read William Vollmann’s Imperial.

There are many, many more, of course (too many, really).

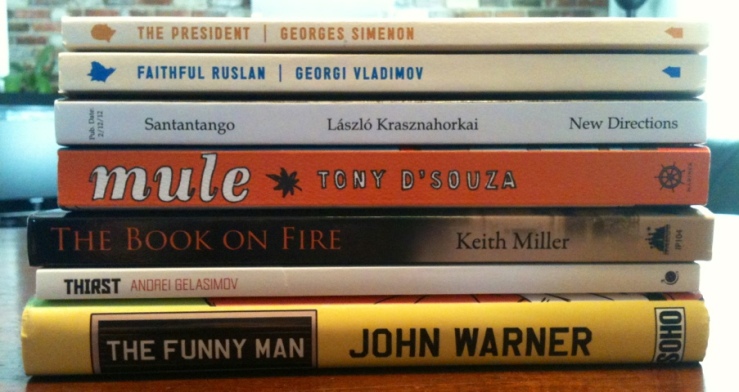

Books people sent me to read and review that look really cool that I will be reading and reviewing at some point in the very near future:

Satantango by László Krasznahorkai: I will read this and review this in the very near future.

The Funny Man by John Warner: Comedy, drugs, celebrity culture.

The Book on Fire by Keith Miller: This one is about a biblioklept. It’s been at the top of my stack for a few months now, but I keep letting myself get distracted.

Thirst by Andrei Gelasimov: Apparently this novella about a maimed alcoholic war vet is funny. (I hate the cover).

Mule by Tony D’Souza: Middle class man sells marijuana cross country. (I love the cover).

Various titles from Melville House’s Neversink line: I’ve got a few in the stack.

Also: I got a Kindle Fire for Christmas. I actually stayed up really late last night reading free public domain books from Hawthorne, Melville, Whitman, and Dickinson; I’ll read a contemporary novel on it this year—Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, perhaps? Suggestions welcome!—and try to review both novel and the process of reading the novel on a warm glowing machine.

And: I’m sure there are a ton of novels that will come out in 2012 that I’ll want to read; I’m already primed for Dogma, Lars Iyer’s sequel to Spurious.

So: What are you guys looking forward to reading in 2012? What did you fail to read in 2011?