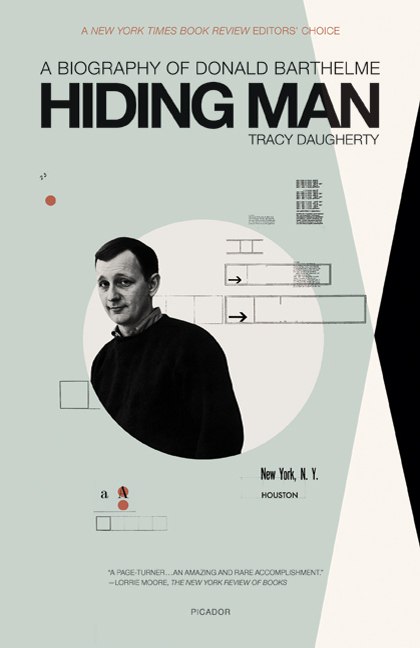

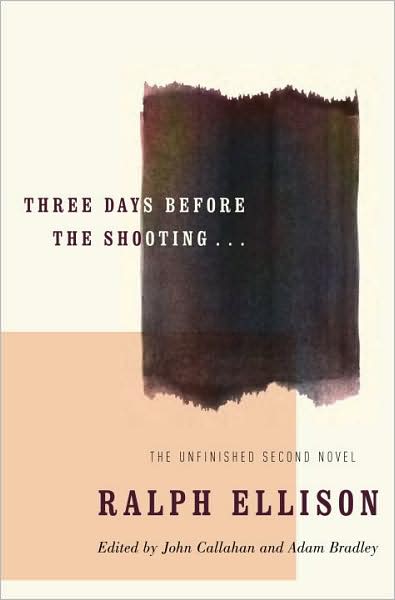

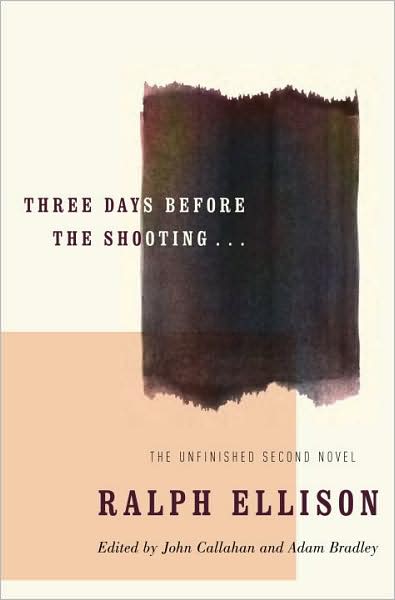

In 1952, Ralph Ellison secured his place in the American literary canon with the publication of his picaresque verbal tour de force, Invisible Man. He never published another novel in his lifetime. Five years after his death in 1994 saw the publication of Juneteenth, a book cobbled together from the sundry drafts that Ellison had spent over forty years crafting and revising. Those papers ran to over 2000 pages. Now, editors John F. Callahan and Adam Bradley have made good on the promise to release an expanded version of Ellison’s proposed second novel. That effort, new in hardback this month from Random House’s Modern Library series, is Three Days Before the Shooting . . ., a massive, complex, and perplexing volume running to 1101 pages — not including editors’ notes, chronology, prefaces, and introductions.

I usually eschew introductions (or at least read them after I’ve read the text proper) in the hopes of not having my reading colored by some critic’s own thoughts, but in the case of Three Days, with its bulk, with its mystery, it seemed necessary to see what Callahan and Bradley had to say. What, exactly, would I be reading? How was it put together? Is there a real novel here? Our esteemed editors point out that:

. . . one might reasonably have expected to find among [Ellison’s] papers a single manuscript very near to completion, bearing evidence of the difficult choices he had made during the protracted period of the novel’s composition. One might have expected, perhaps, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon, a fragmented with a clearly drafted, clearly delineated beginning and middle, whose author’s notes and drafts pointed toward two or three endings, each of which followed and resolved the projected novel as a whole. Or, to cite a more contemporary example, it might have resembled Roberto Bolaño’s 2666; upon its posthumous publication in 2008, Bolaño’s editor remarked that, had the author lived to see it through to publication, “its dimensions, its general content would by no means have been very different from what they are now.” In the extreme, one might have expected something like James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, a glorious mess of a novel that defies the very generic restraints of the form.

Callahan and Bradley pose these novels only as examples to contrast Ellison’s work as “something else entirely: a series of related narrative fragments, several of which extend to over three hundred manuscript pages in length, that appear to cohere without truly completing one another.” There’s a fun laundry list of where and on what Ellison composed the work, including the various types of paper he used and the different machines on which he wrote. The logistics are important from an editors perspective, of course, and as an interested reader it’s fascinating to see how Callahan and Bradley put all of Ellison’s disparate sources together. But what becomes most apparent in their general introduction to the work is that, even as he was always writing, Ellison was stalling, hoping to revise his novel in light of social changes–only, those social changes were happening relatively rapidly. It took Ellison over eight years to produce and edit Invisible Man, a novel that brilliantly captures American identity in the postwar era. For his second novel, Ellison clearly wanted to engage in such a critique again, but the rapidity of social and cultural change seems to have outpaced his ability to write and edit. He satisfied his public and the literary establishment by publishing excerpts of the novel (eight in total, all reproduced in Three Days), but most of his writing career, at least in terms of publishing, was spent writing (and revising) essays and critiques.

Still. Forty years and only eight published snippets? Really? Our fearless editors seem exasperated themselves, writing, “The longer one puzzles over what Ellison left behind, the more maddening it seems that he did not simply will himself to bring the book to a close, that he didn’t find his way to that ‘meaningful form’ he sought.” And there is so much narrative here; Ellison’s major concern — beyond revising in light of cultural and social upheaval — was simply fitting his pieces into a coherent whole. Not that there isn’t a plot. To borrow again from our generous editors:

The basic plot of Ellison’s novel as it emerges in these manuscripts centers upon the connection, estrangement, and reconciliation of two characters. The one is a black jazzman-turned-preacher named Alonzo Hickman, the other a racist ‘white’ New England Senator named Adam Sunraider, formerly known as Bliss–a child of indeterminate race whom Hickman had raised from infancy to adolescence. The action of the novel concerns Hickman’s efforts to stave off Sunraider’s assassination at the hands of the Senator’s own estranged son, a young man named Severen.

Callahan and Bradley go on to point out that, of course, this is simply the bare bones of the plot; that Three Days teems with characters and voices and motifs and strange little riffs. So far, my reading of the book upholds this assertion–and also suggests that the best way to enjoy this book is simply to dive right in. Yeah, that’s right. Ignore all the context. Skip Callahan and Bradley’s prefatory material completely–it’s well-written, highly informative, and will get right in your way. Just start at page one and enjoy Ellison’s rhythm, his inimitable language, his bizarre sense of humor and his deep pathos.

The book opens with a prologue that details a visit Hickman and his congregation make to Washington, D.C. three days before the shooting of Senator Sunraider. They attempt to warn him but are blocked at all turns. Book One then opens immediately with that assassination attempt, seen from the perspective of a journalist named McIntyre who narrates Book One in first-person. The first few chapters are set in the panicked claustrophobia of the post-shooting Senate where police detain everyone present. These chapters detail the strange rumors that circulate about Sunraider, including

. . . the rumor that for a time during his youth the Senator had been the leader of an organization which wore black hoods and practiced obscene ceremonials with the ugliest and most worn-out prostitutes they could find. Like certain motorcycle gangs of today they also engaged in acts of violence and hooliganism and were accused of torturing people — derelicts and such. They were also said to have distributed Christmas baskets and comic books to the poor.

What a great punchline. These early episodes made me laugh out loud at least three times. They’re also rather unsettling, and, more than anything, intriguing. In short, so far the book compels reading, and it’s hard to believe that such inspired riffs won’t add up to greater things. Our editors warn that the book doesn’t so much “end” as simply “stop,” but, right now, I’m fine with that. Ellison fans who don’t own this will want to pick it up forthwith; anyone daunted by its size, scope, or the context of its creation might miss some really great writing. More to come.