Michael Wiley is a mystery writer and professor of British Romantic literature and culture at the University of North Florida. He’s published academic volumes about geography and migration in Romantic literature, but we spoke to him about the latest edition in his detective series, The Bad Kitty Lounge. Dr. Wiley was kind enough to talk to us via email about ambiguity and resolution in mystery fiction, giving readers what they want, and the prospects of Wordsworth with a Glock. The Bad Kitty Lounge is available new in hardcover from Minotuar/St. Martin’s. Read more press at Michael Wiley’s website.

Michael Wiley is a mystery writer and professor of British Romantic literature and culture at the University of North Florida. He’s published academic volumes about geography and migration in Romantic literature, but we spoke to him about the latest edition in his detective series, The Bad Kitty Lounge. Dr. Wiley was kind enough to talk to us via email about ambiguity and resolution in mystery fiction, giving readers what they want, and the prospects of Wordsworth with a Glock. The Bad Kitty Lounge is available new in hardcover from Minotuar/St. Martin’s. Read more press at Michael Wiley’s website.

Biblioklept: Your new novel The Bad Kitty Lounge picks up with P.I. Joe Kozmarski, the protagonist from your first novel The Last Striptease; both books are set in Chicago. When you were working on Striptease did you envision it as the beginning of a series?

Michael Wiley: I did. To tell the truth, The Last Striptease catches the story already in motion. I wrote an earlier Joe Kozmarski manuscript that I called Little Girl Lost, almost got published, and then tucked into a box, where it remains. I liked the character and the settings well enough that I wrote a new manuscript, which became The Last Striptease. I had set Little Girl Lost in August and Last Striptease in September, so when I started writing The Bad Kitty Lounge I decided to set it in October and aim for a series that covers each month of the year. There’s no great logic to aiming for a twelve-book series, but it seems as good of a number as any.

B: There’s a tradition in detective fiction of recurring characters (Chandler’s Marlowe comes immediately to mind). When you are writing these books, do you consciously follow or inject tropes of mystery and crime fiction? How important is it to give mystery readers what they want?

MW: It’s always important to give readers what they want. But readers might not know what they want until a book gives it to them. In genre fiction and mysteries and thrillers in particular, conventions matter, but if a writer sticks too closely to conventions the result is cliché. The key isn’t to ignore the conventions but to finesse them, use them in new ways, invert or subvert them. The best mysteries, I think, are recognizable in form but still manage to surprise us and give us great unanticipated pleasures. Before Chandler’s Marlowe, there’s Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, and before Holmes, there’s Poe’s Dupin. Each of the greats has reinvented the form in big ways and has given readers what they’ve always wanted without knowing that they’ve wanted it. The rest of us innovate where we can.

B: Sometimes though it seems that writers who experiment too much with genre conventions can subvert, invert, or innovate in ways that trample on some of the great pleasures of mysteries and thrillers. I’m thinking explicitly about novels like Jonathan Lethem’s Gun, with Occasional Music, which weds PK Dick with hard boiled noir, or Thomas Pynchon’s recent exercise Inherent Vice. Such books prize ambiguity, which leads to a shaggy dog story. There’s certainly a pleasure in reading them but many of us read mysteries because Dupin or Sherlock Holmes or Marlowe (or whomever) actually solves the case. How important do you think it is to give mystery readers an answer or solution? What place does ambiguity have in your detective fiction?

MW: Right. Most of the best mystery writing right now includes at least some ambiguity, though. I’ve been reading and re-reading James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux books lately, and while each of them solves a case at hand, we never have the sense that Robicheaux has restored a proper order to the universe. Just the opposite: we know that the universe is deeply screwed up and that Robicheaux is as much a part of the problem as he is part of the solution. Aside from that, some of Burke’s villains pop up again in later books even after we’re sure that Robicheaux has put them to rest.

My own books resolve crimes. At the end, we know who did what and when and why. But my books are also full of moral ambiguity. Some of the guilty parties don’t get punished. Some of the innocent parties do. Good people sometimes do bad things for either good or bad reasons. Bad people sometimes do good things. We get answers but we don’t necessarily like them.

B: I realize that I may have been putting carts before horses with some of these questions–can you tell us a little bit about the plot of The Bad Kitty Lounge?

MW: I like carts before horses. Here’s a synopsis that I wrote for the book flap:

Greg Samuelson, an unassuming bookkeeper, has hired Joe Kozmarski to dig up dirt on his wife and her lover Eric Stone. But now Samuelson has taken matters into his own hands. It looks like he’s torched Stone’s Mercedes, killed his boss, and then shot himself, all in the space of an hour. The police think they know how to put together this ugly puzzle. But as Kozmarski discovers, nothing’s ever simple. Eric Stone wants to hire Kozmarski to clear Samuelson. Samuelson’s dead boss, known as the Virginity Nun, has a saintly reputation but a red-hot past. And a gang led by an aging 1960s radical shows up in Kozmarski’s office with a backpack full of payoff money, warning him to turn a blind eye to murder. At the same time, Kozmarski is working things out with his ex-wife, Corrine, his new partner, Lucinda Juarez, and his live-in nephew, Jason. If the bad guys don’t do Kozmarski in, his family might.

In short, it’s a gritty hardboiled mystery set in Chicago. If your sense of humor runs the way mine does, it has some laughs. Booklist Magazine calls it “howlingly funny.” That may be overstating the case, but I appreciate the compliment.

B: Books critics must always be forgiven hyperbole, positive and negative.

You’re a professor of English literature; specifically, you’re an expert on the British Romantic poets. You might tire of this question–and forgive me if so–but do elements of British Romanticism find their way, consciously or not, into your detective fiction? It seems like a detective’s mission would be at odds with the spirit of Keats’s Negative Capability.

MW: From my perspective, it’s easier to deal with the positive hyperbolic criticism than the negative.

I once told an editor jokingly that I planned to write a mystery featuring William Wordsworth with a Glock. To my surprise, the editor was enthusiastic. I suppose there’s a market for these books. Abe Lincoln: Vampire Hunter has been doing well, and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies was a hit.

I mostly think of my day job as a British Romanticist as being separate from my night job as a writer of pulp fiction, but I know that that the two intersect and inform each other. Wordsworth and Raymond Chandler are two of the great English-language locodescriptive writers, and they’ve both influenced my handling of place. William Blake deals with ideas of innocence and experience, good and evil, and heaven and hell in ways that no noir writer has ever surpassed. And Lord Byron is great for moral ambiguity, as is S.T. Coleridge though in different ways.

So, I’ll probably get to that Wordsworth-with-a-Glock manuscript sooner or later.

B: Wordsworth with a Glock sounds great. Then you could write John Keats Vs. The Lamia; make it a graphic novel. Or just a screenplay. For now though, is the next Kozmarski book already in the works?

MW: I see a series here. My friend Kelli Stanley has set mysteries in ancient Rome. She calls them “Roman Noir.” I’ll just add a “tic” and I’ll have “Romantic Noir.” In the meantime, Joe Kozmarski will ride again. St. Martin’s Minotaur has said that they want to publish the third in the series. It’s done, it’s called A Bad Night’s Sleep, and it’s the best one yet. It should be out in 2011.

B: You teach full time and have a family–how do you make time to write? What advice could you give to young writers who want to develop that kind of discipline?

There’s never enough time in the day — or the week or the year — to write a book. There are thousands of excuses for doing something else, and nearly all of the excuses are good. I accept these facts and then write anyway. I write in the morning before breakfast if I can, or write in the evenings after the kids are in bed. I write in between. And when I’m not writing, I’m often thinking about plot, characters, and setting.

I draw from my own experience when I give advice, which is very simply (and annoyingly) this: “Just write.” Writing seems to me to be more of an act of will than of discipline. Don’t spend time worrying that you’re not writing enough; don’t spend time thinking about the act of writing (unless that’s the subject of your short story or novel) — Spend your time writing. Tell your story. Then revise it. Then think of another story and tell it. Oh, and when you’re not telling or revising or thinking of new details for your story, read other people’s stories and learn from them. That seems important too: others have told better stories than I’ll ever tell. I can learn from them. We all can.

B: Have you ever stolen a book?

MW: No. But I hope someone steals one of mine.

The Girl with Glass Feet is the début novel from British author Ali Shaw. Set in the remote archipelago of St. Hauda’s Land and steeped in the traditions of English folklore, Shaw’s novel works in the idiom of magical realism. His titular girl Ida Maclaird suffers from a strange affliction: she’s slowly turning into glass. She returns to St. Hauda’s land in the winter (after a previous summer holiday there) in the hopes of finding a cure. There she meets Midas Crook (whose symbolically overdetermined name seems part and parcel of Shaw’s program), a photographer fascinated by his father’s ghost stories about the isolated archipelago who is trying to capture something of its haunted spirit in his pictures. Together (and with the help of some strange locals) the pair tries to find answers against a melancholy and magical backdrop of tiny winged cows, albino crows, and other grotesques. A sample ghost story, one of many in Glass Feet—

The Girl with Glass Feet is the début novel from British author Ali Shaw. Set in the remote archipelago of St. Hauda’s Land and steeped in the traditions of English folklore, Shaw’s novel works in the idiom of magical realism. His titular girl Ida Maclaird suffers from a strange affliction: she’s slowly turning into glass. She returns to St. Hauda’s land in the winter (after a previous summer holiday there) in the hopes of finding a cure. There she meets Midas Crook (whose symbolically overdetermined name seems part and parcel of Shaw’s program), a photographer fascinated by his father’s ghost stories about the isolated archipelago who is trying to capture something of its haunted spirit in his pictures. Together (and with the help of some strange locals) the pair tries to find answers against a melancholy and magical backdrop of tiny winged cows, albino crows, and other grotesques. A sample ghost story, one of many in Glass Feet— In The Three Weissmanns of Westport, Cathleen Schine transposes the Dashwoods of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility to a dilapidated beach cottage in Westport, Connecticut. When 78 year old Joseph divorces his 75 year old wife Betty, and his mistress essentially forces her from their high-end NYC apartment, Betty rallies by moving to the beach cottage with her daughters, impulsive Miranda, a literary agent, and practical Annie, a library director. The premise may sound like the domain of that most maligned of genres, “chick lit,” a fact that many reviewers tackled when it debuted in hardback last year. Here’s

In The Three Weissmanns of Westport, Cathleen Schine transposes the Dashwoods of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility to a dilapidated beach cottage in Westport, Connecticut. When 78 year old Joseph divorces his 75 year old wife Betty, and his mistress essentially forces her from their high-end NYC apartment, Betty rallies by moving to the beach cottage with her daughters, impulsive Miranda, a literary agent, and practical Annie, a library director. The premise may sound like the domain of that most maligned of genres, “chick lit,” a fact that many reviewers tackled when it debuted in hardback last year. Here’s  Before looking over Joan Schenkar’s exhaustive biography of Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith, I have to admit that I thought of the writer primarily as a practitioner of pulp fiction, the kind of lurid crime tales at home in airport bookshops. In recent years, I’ve come to reevaluate my stance on crime noir in particular (which I wrote about

Before looking over Joan Schenkar’s exhaustive biography of Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith, I have to admit that I thought of the writer primarily as a practitioner of pulp fiction, the kind of lurid crime tales at home in airport bookshops. In recent years, I’ve come to reevaluate my stance on crime noir in particular (which I wrote about  Online auctions allow book-lovers to engage in what could be labeled “biblio-sharking.” Some poor sap needs to clear out his basement to make room for a foosball table or a Jacuzzi, and readers take his books for an extraordinary profit. While the seller may hesitate to dispose of their treasures, I’ll readily pay negligible sums to compensate him for his losses. So, if your rumpus room means more to you than fiction, please please please place your ads on Ebay.

Online auctions allow book-lovers to engage in what could be labeled “biblio-sharking.” Some poor sap needs to clear out his basement to make room for a foosball table or a Jacuzzi, and readers take his books for an extraordinary profit. While the seller may hesitate to dispose of their treasures, I’ll readily pay negligible sums to compensate him for his losses. So, if your rumpus room means more to you than fiction, please please please place your ads on Ebay. Spillane sold hundreds of millions of detective and spy stories during a long career, and the Hammer stories guaranteed him an interested and rabid following. Although private dick Mike Hammer finds himself in any number of slippery situations, Spillane’s central character, rather than any individual plot twist, is what makes these stories both convincing and compelling.

Spillane sold hundreds of millions of detective and spy stories during a long career, and the Hammer stories guaranteed him an interested and rabid following. Although private dick Mike Hammer finds himself in any number of slippery situations, Spillane’s central character, rather than any individual plot twist, is what makes these stories both convincing and compelling. This was the first collection of detective stories I’ve ever finished, and each page dragged me further into a black and white world filled with villains, vixens, and corrupt politicians. The reader becomes an unpaid extra in a B-level film noir.

This was the first collection of detective stories I’ve ever finished, and each page dragged me further into a black and white world filled with villains, vixens, and corrupt politicians. The reader becomes an unpaid extra in a B-level film noir. Michael Wiley is a mystery writer and professor of British Romantic literature and culture at the University of North Florida. He’s published academic volumes about geography and migration in Romantic literature, but we spoke to him about the latest edition in his detective series, The Bad Kitty Lounge. Dr. Wiley was kind enough to talk to us via email about ambiguity and resolution in mystery fiction, giving readers what they want, and the prospects of Wordsworth with a Glock. The Bad Kitty Lounge is available new in hardcover from

Michael Wiley is a mystery writer and professor of British Romantic literature and culture at the University of North Florida. He’s published academic volumes about geography and migration in Romantic literature, but we spoke to him about the latest edition in his detective series, The Bad Kitty Lounge. Dr. Wiley was kind enough to talk to us via email about ambiguity and resolution in mystery fiction, giving readers what they want, and the prospects of Wordsworth with a Glock. The Bad Kitty Lounge is available new in hardcover from

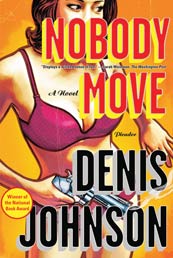

Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move is a tight snare drum of a comedy crime novel. Jimmy Luntz, still decked out in his white barbershop chorus tux (don’t ask) gets into trouble with a big gorilla he owns money too. On the run, he meets smoldering bombshell Anita. More trouble ensues. Nobody Move, originally serialized in Playboy, is a dark, funny genre exercise propelled by Johnson’s sharp dialogue and keen eye for detail. Johnson’s restraint and economy demonstrate writerly chops, but its his story and his characters that made me stay up too late reading last night.

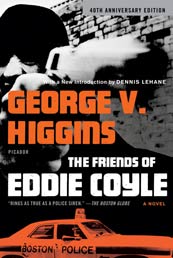

Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move is a tight snare drum of a comedy crime novel. Jimmy Luntz, still decked out in his white barbershop chorus tux (don’t ask) gets into trouble with a big gorilla he owns money too. On the run, he meets smoldering bombshell Anita. More trouble ensues. Nobody Move, originally serialized in Playboy, is a dark, funny genre exercise propelled by Johnson’s sharp dialogue and keen eye for detail. Johnson’s restraint and economy demonstrate writerly chops, but its his story and his characters that made me stay up too late reading last night. I’m kind of embarrassed that I’d never heard of George V. Higgins’s seminal crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the story of a down-on-his luck gunrunner trying to get a break on a three-year sentence. Picador’s new edition celebrates the book’s 40th anniversary. Higgins’s electric dialogue thrusts the reader right into the action, trading narrative clarity for a smoky milieu of backroom deals and gritty alleys. But my phrasing here sounds way too corny and trite. Forgive me, I don’t really know how to write about good crime fiction because I’m so unused to it. I’ll lazily favorably compare The Friends of Eddie Coyle to David Simon’s Baltimore crime epic The Wire.

I’m kind of embarrassed that I’d never heard of George V. Higgins’s seminal crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the story of a down-on-his luck gunrunner trying to get a break on a three-year sentence. Picador’s new edition celebrates the book’s 40th anniversary. Higgins’s electric dialogue thrusts the reader right into the action, trading narrative clarity for a smoky milieu of backroom deals and gritty alleys. But my phrasing here sounds way too corny and trite. Forgive me, I don’t really know how to write about good crime fiction because I’m so unused to it. I’ll lazily favorably compare The Friends of Eddie Coyle to David Simon’s Baltimore crime epic The Wire. I’ve been too engrossed with Coyle and Nobody Move the past few days to do more than skim over Clancy Martin’s How to Sell, a novel about grifters and scam artists in the jewelery world, but I did read and very much enjoy its first chapter, where the protagonist pawns his mother’s wedding ring (“the only precious thing she had left”) and yet still manages to keep reader sympathy (mine, at least). Martin worked for years in the fine jewelery business. He also translates Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Zadie Smith says of How to Sell: “It’s a little like Dennis Cooper with a philosophical intelligence, or Raymond Carver without hope. But mostly it’s like itself.” I like that.

I’ve been too engrossed with Coyle and Nobody Move the past few days to do more than skim over Clancy Martin’s How to Sell, a novel about grifters and scam artists in the jewelery world, but I did read and very much enjoy its first chapter, where the protagonist pawns his mother’s wedding ring (“the only precious thing she had left”) and yet still manages to keep reader sympathy (mine, at least). Martin worked for years in the fine jewelery business. He also translates Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Zadie Smith says of How to Sell: “It’s a little like Dennis Cooper with a philosophical intelligence, or Raymond Carver without hope. But mostly it’s like itself.” I like that.