Hamilton Leithauser, vocalist/lyricist for one of our favorite bands, The Walkmen, shared what he enjoyed reading this past year at The Millions, part of their year-end “A Year in Reading 2009” series (we dig plenty of the literati who contribute to the list, particularly Stephen Elliott, whose essays we’ve long admired, and who says Bolaño’s 2666 is his favorite book this year–but we’ll take the nonliterary route this time, and go with a (semi-)rock star). Leithauser speaks highly of Dave Eggers and Kingley Amis, and cites W.H. Auden as a favorite poet. We think that The Walkmen’s last record You & Me is about as literary as you can get in a rock record–it plays like a collection of interconnected short stories, full of the disillusionment and joy of getting older. We gave You & Me pride of place on last year’s list best-of music list. Here’s “In The New Year,” a song that builds fantasy only to puncture it thoroughly. Great stuff.

Tag: Literature

Distant Star — Roberto Bolaño

Roberto Bolaño’s slim novel Distant Star begins a few months prior to Pinochet’s bloody 1973 coup and continues into the mid-nineties, crossing through several countries in the process. The unnamed narrator (presumably the “Arturo B.” mentioned in a brief preface, surely Arturo Belano, Bolaño’s alter-ego) is so busy with the future of Chilean poetry that the violence of the coup–in which scores of students are arrested, killed, or disappeared–takes him by total surprise. He’s obsessed with a quiet and intense poet close to his age named Alberto Ruiz-Tagle, who seems to be, according to all sources prior to the coup, a harbinger of a new age in Chilean writing. Ruiz-Tagle, it turns out, is actually an Air Force officer named Carlos Wieder, who writes his death-obsessed poetry in a WWII Messerschmitt airplane. Wieder’s sky-written poems cause a sensation (however illegible some are), but not one nearly as great as his magnum opus–a multimedia installation cataloging and detailing Wieder’s sadistic, ritualistic murders of students and other dissidents. His art is beyond the pale of even the new military regime, and he’s forced out of the Air Force to live a life under pseudonyms in other countries, much like the other Chilean exiles who populate this book. Bolaño’s narrator, a savage detective, takes great pains to reconstruct the lives of these escaped artists, but as time passes the truth becomes ever-murkier. He writes at one point that “the melancholy folklore of exile” is “made up of stories that, as often as not, are fabrications or pale copies of what really happened.” The narrator’s detective work, aided by old friends, attempts to reconstruct the whereabouts (or fates) of Chile’s exiles, but more often than not the trails lead to a perplexing pastiche of possibilities–not dead ends, but inconclusive answers. The story builds to a tense, sinister, and perhaps incomplete (yet satisfying) climax as a “real” detective–a former cop turned PI–enlists the narrator to track down a man who may or may not be Wieder. And I won’t spoil what happens after that.

I read most of Distant Star over the course of one afternoon, and then re-read most of it again earlier this week. It seems to me that the book is something of a trial-run for Bolaño’s opus, 2666, and when I say that, I don’t mean to diminish Distant Star at all, only to note that, more so than The Savage Detectives or By Night in Chile, this book is markedly horrific and at times profoundly violent. It is, of course, something of a companion piece for By Night in Chile (both, by the way, translated by Chris Andrews). That book is a confession from a critic-priest who had flourished under the right-wing regime; Distant Star gives us the other side of the story. Distant Star is also an investigation (by way of digression, to be sure) into the relationship between power and art and evil, and there’s a coldness at its core that almost hurts. It is both painful and beautiful. This is not the best starting place for Bolaño. I’ll continue to contend that 2666 is a fine and dandy place to jump in, or Last Evenings on Earth, if 900 pages is too much for you, but if you read those and dig them, you’ll want to read Distant Star, and its evil twin By Night in Chile. In some sense, all of Bolaño’s work (at least what I’ve read so far) composes a grand and (in)complete and sweeping collective body, like Faulkner, who provides Distant Star its epigraph: “What star falls unseen?” Highly recommended.

Literature Is Not Made From Words Alone

Roberto Bolaño, in a 2002 interview, tells us that

. . . literature is not made from words alone. Borges says that there are untranslatable writers. I think he uses Quevedo as an example. We could add García Lorca and others. Notwithstanding that, a work like Don Quijote can resist even the worst translator. As a matter of fact, it can resist mutilation, the loss of numerous pages and even a shit storm. Thus, with everything against it–bad translation, incomplete and ruined–any version of Quijote would still have very much to say to a Chinese or an African reader. And that is literature.

The interview, conducted by Carmen Boullosa, was originally published in Bomb. It’s now collected along with three other interviews, all meticulously annotated (there’s also a fabulous introductory essay by Marcela Valdes) in a collection called Roberto Bolaño: The Last Interview, new from Melville House. While you’re browsing Melville House, I highly, highly recommend Tom McCartan’s column “What Bolaño Read,” which will be ongoing through next week. Great stuff. Biblioklept will run a proper review of The Last Interview later this week (no big surprise for regular ‘klept readers: I love it. Get it. Read it. Give it to the Bolaño fanatic in your life), but in the meantime, back to the quote.

I’ve written so much about Bolaño over the past year yet I’ve never really reflected on his English translators, Chris Andrews (the shorter works) and Natasha Wimmer (the long books), probably because I wouldn’t know how to begin. Reading interviews with Andrews and Wimmer (links above) is enlightening. Andrews attests that he tries to avoid “a translation that is unduly distracting,” and remarks on Bolaño’s epic syntax. Wimmer says she simply tried “to follow Bolaño’s lead,” but admits to her reviewer that she might have missed some puns (“Missing things like that is the translator’s great dread, but it’s probably inevitable occasionally, especially with Bolaño”). In both of the interviews, Bolaño’s translators come off as critical readers whose love of their source material is clearly at the forefront of their project. I have to believe–and have to is the operative term here–that their translations are faithful to Bolaño’s text (and spirit), that they are not, to use the man’s term, a “shit storm” on his oeuvre. But, given Bolaño’s own definition of “literature,” I’d also aver that his masterpiece 2666 could weather any shit storm (hell, the thing was, I suppose, technically incomplete at his death). In any case, I find Bolaño point reassuring, not just in light of his own work, but also within the context of a greater canon of world literature. His suggestion that real literature speaks beyond “words alone,” that storytelling is more than mere verbal tricks and schemes, should be an affirmation to anyone who’s ever been unsure that he’s properly “got” Kafka or Haruki Murakami or Dostoevsky or whomever. And I like that idea quite a bit.

Best Books of 2009

Here are our favorite books published in 2009 (the ones that we read–we can’t read every book, you know). The list includes books new in print after a long time as well as first editions of trade paperbacks. All links are to Biblioklept reviews. The list is more or less chronological, beginning in January of 2009.

The Book of Dead Philosophers — Simon Critchley

Chicken with Plums (trade paperback) — Marjane Satrapi

The 2009 PEN/O. Henry Prize Short Stories

Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image — Michael Casey

Inherent Vice — Thomas Pynchon

A Better Angel (trade paperback) — Chris Adrian

The City & The City — China Miéville

Asterios Polyp — David Mazzucchelli

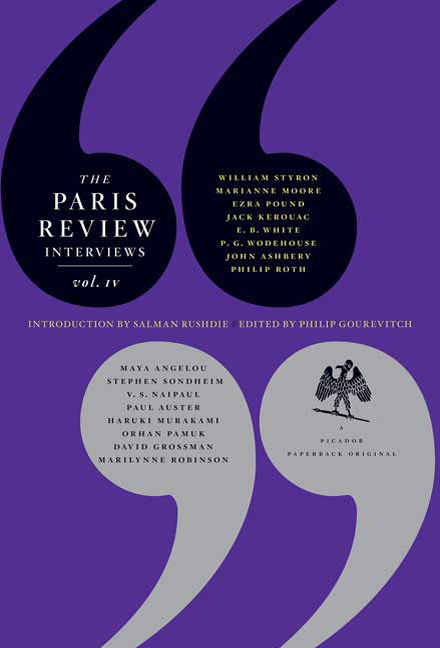

The Paris Review Interviews, Vol. IV

Every Man Dies Alone — Hans Fallada

“Midnight in Dostoevsky” — New Short Fiction from Don DeLillo

Want to read to read the latest from Don DeLillo? Of course you do. Check out “Midnight in Dostoevsky,” via The New Yorker. Still not intrigued? Here’s the first paragraph:

We were two sombre boys hunched in our coats, grim winter settling in. The college was at the edge of a small town way upstate, barely a town, maybe a hamlet, we said, or just a whistle stop, and we took walks all the time, getting out, going nowhere, low skies and bare trees, hardly a soul to be seen. This was how we spoke of the local people: they were souls, they were transient spirits, a face in the window of a passing car, runny with reflected light, or a long street with a shovel jutting from a snowbank, no one in sight.

Cormac McCarthy’s Issues of Life and Death, Hans Fallada’s Complex Resistance, and Jonathan Lethem’s Bloodless Prose

In a 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy famously said that he only cares for writers who “deal with issues of life and death.” He disses Proust and Henry James, saying “I don’t understand them . . . that’s not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange.” Because he has granted so few interviews–and come off so guarded in those he has done–McCarthy’s dictum on “good writers” has perhaps become a bit inflated, elevated from one man’s opinion to a grand litmus test of literary worth. Still, I often find myself putting the books I read under the McCarthy stress-test: do they narrativize the Darwinian drama of life and death? Or are they simply bloodless spectacles of rhetoric, ephemeral social critiques, or faddish forays into solipsism? McCarthy’s targets, Proust and James, arguably do address life and death issues in their works, but when compared to McCarthy’s heroes–Melville, Faulkner, Dostoevsky–the social fictions of Proust and James seem wan, or at least too subtle and overly-coded. The two novels I’m currently working through, Jonathan Lethem’s Chronic City and Hans Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone, illustrate not just the poles of McCarthy’s dichotomy, but also why many readers (myself included) tend to prefer that their novels address matters of life and death.

Every Man Dies Alone, first published in German in 1947, is available for the first time ever in English, thanks to translator Michael Hoffman (if you’ve read Kafka in English, you’ve probably read Hoffman’s work) and the good folks at Melville House. Fallada’s novel tells the story of German resistance to the Nazi regime, not at an aristocratic or militaristic level (this isn’t Valkyrie), or even a literary or philosophical level, but at the level of every day, ordinary existence. After the death of their son in battle, Otto and Anna Quangel initiate a campaign of resistance to the Nazi party, one that is of course doomed from the outset. The Quangels soon involve Eva Kluge, among others, in their covert resistance cell. Kluge is a letter-carrier who becomes disgusted with the moral implications of the regime; she’s also deeply embittered by the way Nazi rule has systemically destroyed her family. Kluge’s peripatetic job helps to enact Fallada’s major rhetorical gesture, a sweeping busyness that vividly recreates the life of ordinary Germans during the rule of the Third Reich. We might begin in Kluge’s mind as she embarks to deliver a letter, only to find ourselves awash in the thoughts of its recipient a few pages later. Fallada’s omniscient third-person narrator moves freely from one character’s consciousness to another’s, shifting fluidly from the immediacy of present tense to the solidity of past tense. It’s modernism (whatever that means)–Tolstoy without the rich and famous, Joyce without the mythos and erudition, but deeply engaging in its scope. WWII has produced a seemingly endless myriad of narratives, yet Fallada’s tome is the first that I’ve experienced of its kind. Perhaps its subject matter–the lives of ordinary Germans and their unsuccessful attempts to resist the mundane evil all around them–is simply not the stuff that we want from our war stories, and perhaps this is why the book has been absent so long from an English translation. It’s evocative of a world that I had never really considered before: after all, the narrative of WWII is far easier to comprehend if you retain the simplicity of the good guys (the Allies), the bad guys (the Nazis), and the victims (the Jewish population of Europe). Ordinary Germans have only one place in this uncomplicated system, which is why the story of the Quangels and their cohort is so profound (oh, the Quangels are based on the real-life Nazi resisters Otto and Elise Hampel, if you must know). Driven in part by despair, they seek to forge meaning in their lives, even if its at the cost of death, or the horrors of a concentration camp. To return to McCarthy’s caveat, Fallada’s novel is a work that dramatizes life and death against a decidedly unheroic backdrop, a novel that makes its reader repeatedly ask himself whether or not he would be, to use another McCarthyism (from The Road) one of the “good guys.” Great stuff, and so far one of the better novels we’ve read this year. Go get it.

It’s perhaps unfair to lump Lethem’s latest in a review with Fallada, given the historical complexity of Every Man Dies Alone‘s milieu. Still, I’ve been reading my review copies of both novels over this long weekend, trying to catch up, and I find that I would almost always rather pick up Fallada’s book. It compels me, whereas, half way through Chronic City, I still find nothing to care about, no risk, no cost, no guts. No matters of life and death. The novel centers around former-child actor Chase Insteadman, whose directionless existence seems to thematically underpin the book. Chase moves from party to party in a fictitious Manhattan, charming various socialites and keeping boredom (marginally) at bay. He soon hooks up with Perkus Tooth, a marijuana-addicted pop culture critic, whose characteristics will be familiar to pretty much anyone who earned a liberal arts degree in college. Tooth seems to function largely as a mouthpiece for Lethem to espouse various opinions on movies and books and art. It’s a clumsy device as it doesn’t shade the character–it’s simply Lethem couching his cultural criticism in the comfort of a work of fiction. In a particularly telling scene, Perkus picks up a copy of The New York Times and thinks that it feels too light. He looks up at the right-hand corner: “WAR FREE EDITION. Ah yes, he’d heard about this. You could opt out now.” Perkus seems to deliver the line as a criticism, but it’s Lethem who’s opting out. He drops hints of destruction and annihilation and disintegration in the novel–there’s a giant tiger on the loose somewhere in Manhattan; Chase’s fiancée floats estranged in space, stranded on the International Space Station; a crooked mayor is up to dastardly shenanigans–but Lethem protects his characters from it all in an insulating cocoon of marijuana smoke and pop trivia. Their forays into the darkness of Manhattan’s mysteries are meant to play both humorously but also with enough danger to fully invest a reader’s attention (think of Lethem’s more successful sci-noir Gun, with Occasional Music, or his detective thriller Motherless Brooklyn). Instead, the adventures fall flat, collapsing back into Perkus’s apartment, a vortex of (ultimately meaningless) pop culture. While the novel is by no means terrible–it’s well-written, of course–there is simply a tremendous lack of the “life and death” stuff that McCarthy–and other readers–require. In short–and in contrast with Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone–it does not compel itself to be read. Which is a shame of course. I still think Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude was one of the finest books of the decade, and I was deeply disappointed in his last novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet. Chronic City is a much finer book than that silly train wreck, but it lacks the urgency of Lethem’s finest works, Fortress and Motherless Brooklyn, which temper a love of popular culture with genuine characters and an affecting plot.

I’ll conclude by returning to Cormac McCarthy, this time to his latest interview (in The Wall Street Journal). He says, on writing novels: “Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing.” And later: “Creative work is often driven by pain. It may be that if you don’t have something in the back of your head driving you nuts, you may not do anything.” For McCarthy, literature, in its final product–the reader reading the book–is the direct communication of the pain of creation, the awkward and incomplete translation of ideas exchanged from author to audience. Perhaps the pain was too much for Fallada, who died in 1947 of a morphine overdose, but that pain–that spirit–exists in the book. A similar spirit exists in Lethem’s earlier works; I’d love to see him tap into it again in his next venture.

Every Man Dies Alone is now available in hardback from Melville House.

Chronic City is now available in hardback from Double Day.

Bored Booksellers and Nauseated Novelists

Bored? Check out new(ish) WordPress blog Bored Bookseller Musings. Good writing on books, bookstores, rude customers, and other literary(ish) matters. In a recent(ish) post, the Bored Bookseller pointed our direction to a new(ish) essay by Zadie Smith, where the White Teeth author discusses “novel-nausea.” (Smith’s essay is really just a ploy to promote her new book of essays, Changing My Mind).

A Truth Universally Acknowledged — 33 Great Writers on Why We Read Jane Austen

In A Truth Universally Acknowledged, editor Susannah Carson collects thirty-three short essays on Jane Austen. In her introduction, Carson notes that each “of these essayists has taken a shot at defining and explaining Austen’s place both in the literary canon and in the cultural imagination.” And while there’s no mention of Austen’s recent tangles with zombies and sea monsters, the collection does cover quite a route of the cultural imagination that Carson promises. How could it not? There are short (and longish) essays from E.M. Forster, W. Somerset Maugham, Martin Amis, and C.S. Lewis, all proffering different reasons why Austen rules. Contemporary writer Susanna Clarke scolds those of us who might mistake film and TV adaptations as authentic representations of the lady’s work: “Austen wasn’t a visual writer,” Clarke writes, ” Her landscapes are emotional and moral–what we would call psychological.” Harold Bloom goes as far as to suggest that, “Like Shakespeare, Austen invented us.” Bloom’s usual Oedipal anxiety manifests itself in a more palatable line: “Because we are Austen’s children, we behold and confront our own anguish and our own fantasies in her novels.” (Never fear, Bloom gets some axe-grinding in as well: “Those who read Austen ‘politically’ now are not reading her at all.” Thank you again, oh great master critic, for telling us how to read our books). Benjamin Nugent gets pragmatic, seeing Pride and Prejudice as something of a self-help book: “Young nerds should read Austen because she’ll force them to hear dissonant notes in their own speech they might otherwise miss, and open their eyes to defeats and victories they otherwise wouldn’t even have noticed.” One of our favorite writers, Eudora Welty, writes a loving appreciation of the marvel of just how Austen constructed the complex ironies of her works: “Each novel is a formidable engine of strategy.” Rebecca Mead’s “Six Reasons to Read Jane Austen” is both funny and convincing. Reason four: “Because we are made to in school.” Mead’s little essay would be a worthy primer for any high school senior dreading wading into Pride and Prejudice. The great American critic Lionel Trilling points out, as those high schoolers know, that Pride and Prejudice “is the one novel in the canon that ‘everybody’ reads.” He wants you to know that of “Jane Austen’s six great novels, Emma is surely the one that is most fully representative of its author.” He makes a good case for this argument as well, comparing it to the “difficult” books of Proust, Joyce, and Kafka–company that we don’t always associate with Austen. Indeed, many of the essays here focus on Austen’s lesser-read volumes–Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, Emma–and to a positive end: these essayists will make you want to read these books. And isn’t that what real literary criticism should aim to do anyway–make the reader read the book herself, think critically about it herself? While Austen is hardly in need of a revival, A Truth Universally Acknowledged does a lovely job of balancing academic criticism with a popular appeal. Like Austen’s own work, it tempers social critique with sharp humor. A Truth will, of course, appeal mostly to Austen fans (many of whom will surely find it indispensable), but it’s also the sort of volume that will find a place in the hearts of those who simply love to read great writers writing about great writers. Recommended.

A Truth Universally Acknowledged is new in hardback this month from Random House.

Bibliokitchen: Mulatto Rice

At the beginning of Zora Neale Hurston’s novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Janie returns from the Everglades to Eatonville in ragged overalls to a gossipy and unwelcoming town. The one exception is her best friend Phoeby, who brings Janie a “heaping plate of mulatto rice.” Janie gobbles up the simple, delicious meal, even as Phoeby notes that it “ain’t so good dis time. Not enough bacon grease.” She does however concede that “it’ll kill hongry.” No doubt.

We’ve always been intrigued by mulatto rice. What could it be? Is the dish still around today, but under a new name? Although the term “mulatto” has fallen into disuse, and perhaps distaste (just ask Larry David if you don’t believe us), organizations like mulatto.org have also taken a certain ownership of it. For Hurston, mulatto rice is a positive thing. Hurston could have had Phoeby bring any number of dishes to her friend Janie, so it’s telling that she chooses “mulatto rice” as a homecoming meal. The dish represents a communion, an admixture that reflects Janie’s multiracial identity as well as her resistance to gender-typing. “Mulatto” is also probably etymologically akin to the word “mule,” and if you’ve read Eyes, you know that mules are a major motif in the story. But enough literazin’.

Down to the nitty-gritty–we made up a mess of mulatto rice tonight thanks to a recipe from The Savannah Cook Book by Harriet Ross Colquitt. Not that we found this 1933 cookbook ourselves. No, the real merit here goes to the very cool website Take One Cookbook, which explores the history and culture and sociology behind old, weird cookbooks–all while making the recipes. Colquitt’s recipe, via Wendy at Take One Cookbook (see Wendy’s version here):

Mulatto Rice

This is the very chic name given to rice with a touch of the tarbrush.

Fry squares of breakfast bacon and remove from the pan. Then brown some minced onion (one small one) in this grease, and add one pint can of tomatoes. When thoroughly hot, add a pint of rice to this mixture, and cook very slowly until the rice is done. Or, if you are in a hurry, cold rice may be substituted, and all warmed thoroughly together.

The rice is very easy to make and very, very tasty. We substituted green onions for a small onion, and used a hickory-smoked bacon that infused the rice with a lovely sweetness (we also included a tablespoon of brown sugar right after the tomatoes). We served the dish, pictured above, with ham steaks and fried green tomatoes with a spicy yogurt sauce. Hearty and rich and satisfying–just the sort of thing one wants to eat after a soul-searching quest (or maybe just a long day). Recommended.

Best of the Aughties

So, this is Biblioklept’s 500th post [pauses for applause].

Thank you, thank you. To mark the special occasion, we’ve artfully and scientifically compiled a list of the best stuff of the aughties (or 2000s, or whatever you want to call this decade that’s ending so soon). We know the year’s not over yet, and we readily admit that our list is incomplete: we didn’t read every book published in the decade, listen to every record, watch every film, etc. So, feel free to drop a line and let us know who we forgot (or, perhaps, snubbed).

Here, in no particular order, is the best of the past decade:

Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Children of Men, The Fiery Furnaces, The Wire, Kill Bill, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikushi (Spirited Away), The Believer, Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” (and its marvelous video), David Foster Wallaces’s essays in Consider the Lobster, Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke, Animal Collective, Barack Obama, Terrence Malick’s The New World, Mad Men, Deadwood, Dave Chappelle, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Mitch Hedberg, R. Kelly, YouTube, Drag City Records, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Nathan Rabin’s “My Year of Flops,”

Chris Adrian’s The Children’s Hospital, Extras, Harry Potter on Extras, Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Missy Elliott’s “Get Ur Freak On,” Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, Pixar movies–especially the latest three: WALL-E, Up, and Ratatouille, McSweeney’s #13 (the Chris Ware Issue), Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, that time the Shins were on Gilmore Girls, the first six episodes of The OC, Arrested Development, Nintendo Wii, Andre 3000’s “Hey Ya!,” The Office, Will Ferrell, Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, Picador Books, Donnie Darko,

Veronica Mars, The Venture Brothers, Home Movies, the third Harry Potter movie, Wikipedia, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude, DFW’s Oblivion, especially “The Suffering Channel,” Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon commencement address, Wonder Showzen, Toni Morrison’s A Mercy, the totally goofy but totally fun troubadour sequence from Gilmore Girls with Yo La Tengo, Thurston, Kim, and daughter Coco Haley, and Sparks jamming, OutKast’s Stankonia, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Devil’s Backbone, The Orphanage, Cat Power’s “Willie Deadwilder,”Flight of the Conchords, Girl Talk’s Night Ripper, The Daily Show with John Stewart, The Colbert Report,

Andy Samberg’s Digital Shorts, Autotune the News, Tim Tebow, Panda Bear’s Person Pitch, Nels Cline’s guitar solo in “Impossible Germany,” Judd Apatow, Be Kind Rewind, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Thrill Jockey Records, I Heart Huckabees, Chris Bachelder’s U.S.!, David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE, Fennesz’s Endless Summer, Gmail, the Coens’ No Country for Old Men, MF Doom (all iterations), Broken Social Scene’s You Forgot It in People, Satrapi’s Persepolis, UGK’s “International Player’s Anthem,” Bob Dylan’s “Things Have Changed,” Bonnie “Prince” Billy,

The Silver Jews’ Tanglewood Numbers, lolcatz, Once, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, the Coens’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?, web two point oh, 30 Rock, Belle & Sebastian’s “Stay Loose,” It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Philip Pullman’s The Amber Spyglass, Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man, WordPress, Jim O’Rourke’s Insignificance, the first season of Battlestar Galactica, Superbad, half a dozen or so short stories by Wells Tower, David Cross’s Shut Up, You Fucking Baby!, Drunk History, the action sequence at the end of Tarantino’s Death Proof (and especially the joyous, headcrushing final shot), Slavoj Žižek’s Violence, The Royal Tennenbaums, the first 20 minutes of Gangs of New York,

Firefox, the increasing and continuing availability of English translations of authors like Roberto Bolaño and W.G. Sebald, Bill Murray, Margot at the Wedding, Rachel Getting Married, Top Chef, The Dirty Projector’s Bitte Orca, Battles’ “Atlas,” Revenge of the Sith, Sarah Vowell, Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, Christoph Waltz’s bravura performance in Inglourious Basterds, the surreal animations of Carson Mell, Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, Tina Fey’s impression of Sarah Palin, David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, Neko Case’s “Star Witness,” Jason Statham, The Pirate Bay, HDTV, Charles Burns’s Black Hole, &c . . .

New Cormac McCarthy Interview

There’s a very cool new interview with Cormac McCarthy, published yesterday at The Wall Street Journal, of all places. McCarthy speaks frankly about the movie adaptations of his work, including John Hillcoat’s upcoming (and long-delayed) adaptation of The Road. He also proffers this nugget, explaining why he prefers novels to short fiction: “Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing.” Sure. McCarthy also talks about the book he’s writing now: “It’s mostly set in New Orleans around 1980. It has to do with a brother and sister. When the book opens she’s already committed suicide, and it’s about how he deals with it. She’s an interesting girl.” But why are you still here? Go read the interview.

Lucinella — Lore Segal

The story of a group of poets and critics in the late 60s/early 70s NYC should not be so fun or rewarding. From its first page, Lore Segal’s novella Lucinella invents itself as a scathing satire of writers and would-be writers. Segal’s book paradoxically reveres its subject matter, a back-biting and insular literati; and yet at the same time it exposes their solipsistic, narcissistic, cannibalistic shortcomings. These are not particularly generous people, but they are somehow endearing.

Lucinella takes first-person authority to tell the story–and boy does she take authority, bending reality, reason, and narrative cohesion to fit her whim. Lucinella is a poet (a minor poet, perhaps), and Lucinella is very much a poetic action, an act of creation in thirteen parts. The story begins with our (utra-)self-conscious heroine at the idyllic artists’ retreat Yaddo, where she’s ostensibly trying to compose a poem about a root cellar but really just having a grand ole time with a host of notable intellectuals, the poets and critics who will populate the book. “I will make up an eye here, borrow a nose or two there, and a mustache and something funny someone said and a pea-green sweater, so it’s no use your fitting you keys into my keyholes, to try and figure out who’s who,” Lucinella tells us. No worries, Lucinella, we had no idea who, if anyone, your Betterwheatling and Winterneet and Meyers were based on–heck, it took us a few pages to figure out that your Zeus was, um, y’know, that Zeus.

Segal’s (or Lucinella’s) inventions work within a hyperbolic schema set to slow burn. Describing a fellow poet of greater renown:

This Winterneet walking beside me has walked beside Roethke, breakfasted with Snodgrass and Jarrell–with Auden! Frost is his second cousin; he went to school with Pound, traveled all the way to Ireland once, to have tea with Yeats, and spent the weekend with the Matthew Arnolds. He remembers Keats threw up on his way from anatomy; Winterneet says he admires Wordsworth’s poetry, but couldn’t stand the man.

This is pretty much Lucinella‘s program: plausibly esoteric literary references running amok into sublimely surrealistic sketches. If you don’t like that, take your sense of humor to its doctor. Lucinella’s time at the haven of Yaddo is soon up, and she must return to the monster of Manhattan, where young poet William (despite his too-thin neck) shows up at her doorstep to fall in love and eventually marry her. The two attend every literary party, where they feel alternately bedazzled, thrilled, or–mostly–slighted. William, composer of a never-quite-finished epic about Margery Kempe, takes his snubs especially hard, even when he’s being celebrated (and published). We weren’t there, but it seems that Segal evokes her Manhattanite milieu with painterly (or perhaps cartoonly) accuracy. Really, the infighting intellectuals are reminiscent of poseurs and scenesters of any time and place. Lucinella and William go to parties, throw parties, complain about parties, and throw fits like children when they don’t get invited to parties. It’s all very real and very silly and very funny. In one (literally) fantastic set-piece (okay, the whole book might be a fantasy set-piece), Lucinella meets Old Lucinella and Young Lucinella at a party, giving her an(other) opportunity to critique herself. “There’s old Lucinella, the poet,” says one character. “She hasn’t written much in these last years. Used to be good in a minor way” comes the nonchalant reply. Young Lucinella fares no better, although she does manage an affair with William (don’t worry, Lucinella proper hooks up with Zeus in one of the book’s strangest flights of fancy).

The real seduction, as Lucinella points out at a party (of course), is her attempt to seduce her reader into a trenchant unreality that the poets and critics pretend is reality even as they bemoan the reality that their addiction to unreality is their main reality. Yeah. It’s all a bit surreal, and it all comes to a head quite pointedly twice in the novel. The first unmasking occurs at a symposium where the group holds forth on weighty matters – “Why Read?” – “Why Write?” – “Why Publish?” The house lights come up to reveal our fretting poets addressing an empty hall. Even in 1970, no one cares about reading and writing and publishing. And it’s not just the symposium–when Lucinella hosts a party for her pal Betterwheatling, who’s just published a collection of a criticism, she’s shocked to realize as the party dwindles that, not only has she not read his new book, she’s never read anything he’s written. But that’s not all: “I can tell, with the shock of a certitude, by the set of the line of Betterwheatling’s jaw, by the way his hair falls into his forehead, that Betterwheatling has never read a line I have written either and I flush with pain.” Betterwheatling’s punishment: “I’ll never invite him to another party!” Ahhh . . . the petulance. Oh, all the backstabbing and perceived slighting and posing and posturing leads up to an apocalyptic climax, complete with a proper de-invention of Lucinella. It’s all really great.

If Lucinella is light on plot–which we don’t really think it is, despite its slim build, light weight, and 150 or so pages–it’s big on ideas and even bigger on voice. Lucinella is kinda like that crazy art chick you knew in college who was always working on some project that never quite came to fruition, and her cohorts are just the sort of mad loonies you spend time alternately ducking calls from or hoping to run into at a party (depending on your mood). Her evocation of the youthful excitement and nascent romance of poetry reminds us of some of Roberto Bolaño‘s work, particularly the joyful jocularity of Garcia Madero’s section of The Savage Detectives (Segal’s volume is in no short supply of exclamations points). The book builds to a massive millennial climax, a hodgepodge of social consciousness movements and poetry and block party–a moveable feast of paranoia and art and possibility and good clean fun, and, more than anything else, the death-sentences we impose upon ourselves. But we’re overextending our review. Let’s just say that the book is great, and if you love books that both simultaneously mock and valorize the creative process, you’ll probably dig Lucinella’s metafictional tropes. Highly recommended.

Lucinella is in print again for the first time since the 1970s thanks to indie stronghold Melville House Publishing.

On Cult Books

I finished Lore Segal’s lovely and perplexing 1976 novella Lucinella today. It’s a witty and rewarding little book that deserves its own review, of course, and I’ll post one later this week. Lucinella is new in print again for the first time in a few decades courtesy of the good folks at Melville House Publishing. The jacket and the press release Melville House sent me both trumpet the book as a “cult classic.” I’ve been reading a number of so-called “cult books” lately–William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, and John Crowley’s Little, Big. But I’m not really sure what a “cult book” might be. It got me to thinking, of course, and before I went to that ersatz oracle of our time (i.e., a Google search), I thought I’d try to define “cult book” in my own terms:

First, to be clear, a cult book is not (necessarily) a book about cults. It’s a book that has a cultish following (i.e., a group of devoted (perhaps obsessive) fans who work to push the work on anyone who will listen to them).

Second, cult books tend to address or include subject matters and issues outside of mainstream tastes (whatever that means). Of course, what’s open to public discourse changes over time, so what was once a cult book, over time, can soon move into mainstream or even canonical tastes. Hence, a large number of books and authors that once might have been cult are no longer cult.

But this doesn’t seem satisfactory: James Joyce’s Ulysses had to be initially smuggled into America; it’s now a canonical standard. William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch faced similar obscenity charges; decades later, Burroughs starred in a Nike ad. Yet, it seems that despite their eventual “mainstreaming” both books have something of a cult status–yet they don’t seem to need a cult the way that Gaddis or Lowry might. But what about Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy? It clearly needs a cult to push it on people in the hopes of it actually being read, despite its canonical status. Which brings us to defining point three:

Third, the cult in question can not be purely academic. Faulkner would probably be a cult author if it weren’t for English professors and teachers with their syllabi and whatnot.

So, what is a cult novel? I have to think that, based on my definitions, cult status is always malleable. Thanks to the internet, readers have greater access to other readers, not to mention an exponentially expanded market of books to access. So I have to think back to high school and college, to those books that friends thrust on me, saying simply, “Read this, you have to,” books that I thrust on others, books that were secreted from hand to hand, clandestinely, until their covers had to be fixed with Duck tape. I think about Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas; anything by Kurt Vonnegut; Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar; anything by Charles Bukowski; Tropic of Cancer (or was it Tropic of Capricorn?). Antony Scaduto’s Bob Dylan biography made the rounds in my circle of friends, as did the Led Zep bio, Hammer of the Gods.

There was also a pirate copy of The Anarchist Cookbook that someone had downloaded off of something called the internet (this was 1994 or 1995) and printed on a dot matrix printer. William Burroughs, of course. William Gibson. Anthony Burgess. Philip K. Dick. Cerebus. Aldous Huxley (especially Ape and Essence). Lolita. On the Road. Camus. Kafka. In college: John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse. J.G. Ballard. Douglas Coupland. David Foster Wallace’s Girl with Curious Hair, a book literally pressed on me my freshman year by a friend who simply could not believe I had never read Wallace. To some embarrassment, I suppose, Irvine Welsh. Thomas Pynchon. Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach. After college, a refinement I suppose (grad school ironing out some kinks of course): Blood Meridian. W.G. Sebald. Roberto Bolaño. Jorge Luis Borges. The list goes on; I’m sure I’m forgetting hundreds. (Normally, I’d hyperlink most of these authors and books to Biblioklept posts, but there’s just too many. Interested parties, if they exist, may use the search feature).

My list is pretty expansive I suppose (and it’s truncated to be sure), and I concede that the term “expansive” seems at odds with the term “cult.” It seems that all literature that lasts must first build a cult, and I guess that’s a good thing. Anyway–I eventually did google “cult novels” and here’s a few lists. Plenty of overlap with some of the above citations, and some stuff I didn’t think of as well. Also, stuff that I think is too canonical, but, again, make up your own mind:

The Telegraph‘s 50 Best Cult Books

The Cult’s List (chuckpalahniuk.net)

We like this one from Books and Writers

And of course, we’d love to hear from you, dear reader.

The Paris Review Interviews, IV

The Paris Review Interviews, IV, new this week from Picador, continues a great tradition of writers discussing their motivations, inspirations, methods, and, inevitably, other writers. Volume IV collects sixteen author interviews and is perhaps a bit heavier on contemporary writers than past volumes have been, showcasing current luminaries like Haruki Murakami, Orhan Pamuk, Paul Aster, and Marilynne Robinson. Although most of the interviews take place after the 1970s (with half in the past two decades), elder statespeople like William Styron, Marianne Moore, and the venerable Ezra Pound are also present.

Pound’s interview from 1962 is paradoxically revealing in its guardedness: one senses that the aged poet is trying to edit as he speaks, to achieve some sort of perfection. It’s a bit sad too, as Pound, holed up in a sort of self-imposed exile in an Italian castle, admits, “I suffer from the cumulative isolation of not having had enough contact–fifteen years of living more with ideas than with persons.” (On a less-serious note, however, he also praises Disney’s 1957 film “Perri, that squirrel film, where you have the values of courage and tenderness asserted in a way that everybody can understand. You have got absolute genius there.”)

As one might expect, Jack Kerouac comes off as the complete opposite, talking about his troubles with editor Malcolm Cowley, problems with poetry and prose, and Neal Cassady. There’s a free-flowing verbosity to Kerouac’s speech, but also an intimacy. It’s really quite beautiful. At one point, he gets one of the two poets interviewing him, Aram Saroyan, to repeat each line of Poem 230 from Mexico City Blues as he reads it aloud (Kerouac claims he wrote the poem “purely on morphine.”) As they recite the poem over several pages, Kerouac steps outside of it every now and then to compliment Saroyan’s reading or to critique a particular line, or simply to explain what he was trying to do with his words. We’re not huge fans of Kerouac’s writing, but after this interview, we wanted to be. (Later in the book, a surprised P.G. Wodehouse on Kerouac: “Jack Kerouac died! Did he?” Interviewer: “Yes.” Wodehouse: “Oh . . . Gosh, they do die off, don’t they?” Yes, they do).

One of the stranger interviews in the books is between James Lipton, of all people, and composer Stephen Sondheim. Although we don’t doubt the literary merit of Sondheim, the interview does seem a little out of place (although we will attest that the interview with Maya Angelou convinced us to give her a little more cred. A little). Elsewhere, E.B. White asserts that “You have to write up, not down” to children, and Haruki Murakami sheds insight into his own methods and passions (he often conceives his protagonist as a twin brother, lost at birth; his favorite director is Aki Kaurismäki; he’s thrilled to be mentioned in the liner notes of Radiohead’s Kid A). Murakami also talks about the writers he loves, admires, and feels insecure around (he’s shy to meet Toni Morrison at a special luncheon).

Of course, Murakami’s not alone–there’s plenty of writers dishing on writers here. When we reviewed Volume III of The Paris Review Interviews last year, we noted that both Evelyn Waugh and Raymond Chandler take the time to dis William Faulkner in their interviews. Volume IV kicks off with William Styron, who kinda sorta disses Faulkner as well, saying that “The Sound and the Fury . . . succeeds in spite of itself. Faulkner often simply stays too damn intense for too long a time.” Or Marianne Moore, on fellow poet Hart Crane: “Hart Crane complains of me? Well, I complain of him.” Ah, writers . . . great to know they can be as petty and self-absorbed as the rest of us. And it’s that humanity that shines through in these interviews. The series’s greatest accomplishment is its ability to reveal the frailties and insecurities of its subjects, but also their true personalities and tastes. Many writers work hard to control how they are perceived; cultivating a persona, one often aloof, academic, or roguish, is perhaps key to a successful writer’s identity. The interviews here are never fawning, nor do they aspire to sensationalism in revealing their subjects. Instead, each works as a neat, detailed, and very engrossing little portrait of a fascinating personality. Highly recommended.

Doomed He Was

So, instead of grading essays like I should’ve today, I reread D. H. Lawrence’s essay on Edgar Allan Poe, collected in the former’s incomparable Studies in Classic American Literature. Lawrence asserts that Poe is “absolutely concerned with the disintegration-processes of his own psyche,” and goes on to try to prove this over a close-reading of some of Poe’s most famous tales, including “Ligeia” and “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Lawrence concludes his essay a bit melodramatically, but it seems to suit Poe’s depraved dilemmas:

But Poe knew only love, love, love, intense vibrations and heightened consciousness. Drugs, women, self destruction, but anyhow the prismatic ecstasy of heightened consciousness and sense of love, of flow. The human soul in him was beside itself. But it was not lost. He told us plainly how it was, so that we should know.

He was an adventurer into vaults and cellars and horrible underground passages of the human soul. He sounded the horror and warning of his own doom.

Doomed he was. He died wanting more love, and love killed him. A ghastly disease, love. Poe telling us of his disease: trying even to make his disease fair and attractive. Even succeeding.

Actually, a University of Maryland Medical Center study finds that rabies likely caused Poe’s death, not love, as Lawrence suggests. Rabies. Not drugs or women–or love–rabies. How’s that for a “disintegration-process”?

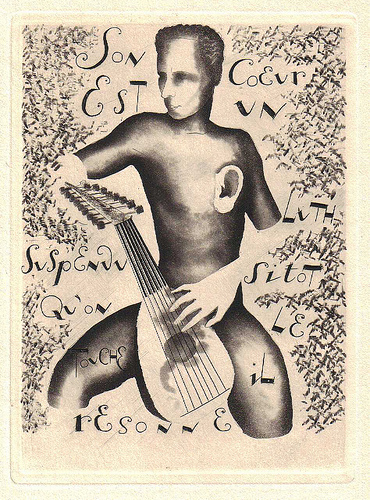

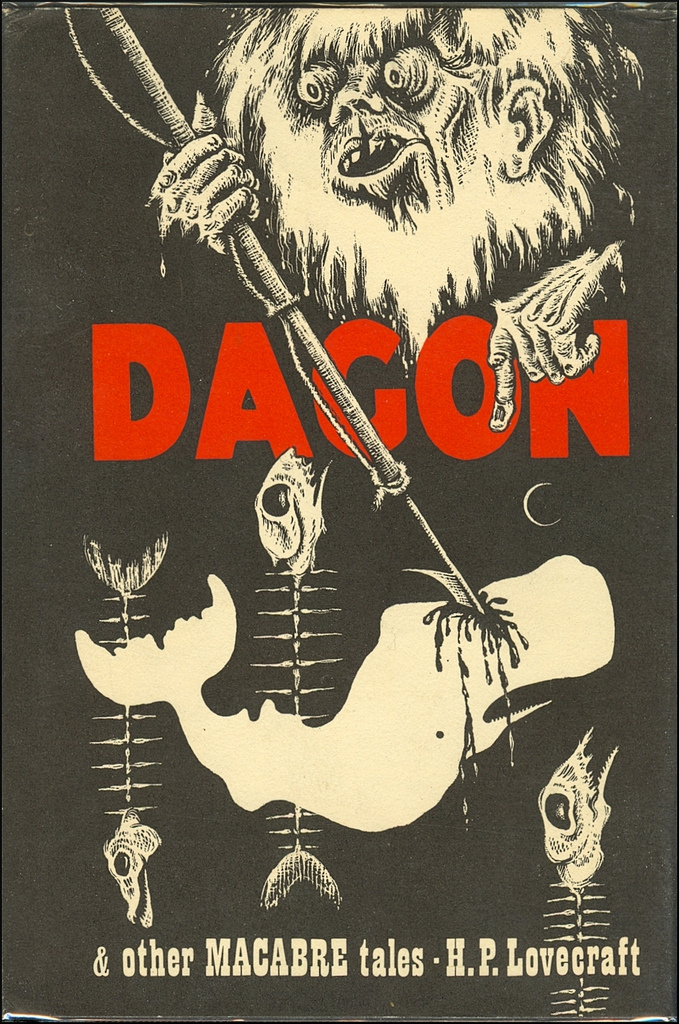

Alexeieff’s “Usher” Aquatints, Lovecraft’s Dagonic Covers, and Henson’s Monster Maker

Halloween fun time:

Excellent gallery of Alexander Alexeiff’s aquatint illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Fall of the House of Usher” via A Journey Round My Skull (what a fantastic site).

Alexeieff’s moody tints and stark designs beautifully match Poe’s gloomy tale. (We just love the lyrical and melancholy opening paragraph–all those thudding ds, low, somber o’s, and lilting ls). His rendering of Usher’s maniac composition is particularly ethereal:

For more Halloween fun, check out this gallery of HP Lovecraft covers via Fantasy Ink. Spooky (and, alternately goofy) designs. We like this jam:

If you like your pictures moving and with sound yet still highly-stylized, check out Jim Henson’s “The Monster Maker,” from Henson’s short-lived but well-beloved series The Jim Henson Hour.

Blood’s a Rover — James Ellroy

A few things up front: this can’t really be a proper review of James Ellroy’s Blood’s a Rover as I’m less than a 100 pages into it and its over a 600 pages long. So far though, the book is fantastic, and has completely ameliorated my mistaken impression of what, exactly, Ellroy is doing. You see, I had long thought of Ellroy, author of L.A. Confidential and The Black Dahlia, as a writer of potboiler genre-fiction–which is to say I never considered him a “serious” writer. But when advanced press for Blood’s a Rover came out, I couldn’t help but ask for a review copy. The idea of an alternate history of the late sixties/early seventies, set to a backdrop of black militant movements, Cuban revolution, and heroin dealing, complete with historical figures like Howard Hughes and J. Edgar Hoover seemed pretty cool.

The opening scene of Blood’s a Rover, a breathtaking armored car robbery, quickly establishes the book’s tense, terse pacing telegraphed through Ellroy’s signature simple sentences (his style: subject-verb-object, repeat–with the occasional clause or adjective thrown in for flair). Ellroy’s rhetorical style perfectly matches his plot, as sentence after sentence hammers away depictions of lurid, unrelenting violence. In a sense, Blood’s comes across as the evil twin of Thomas Pynchon’s recent novel Inherent Vice. Both novels threaten to crush the reader under the densities of their plots, yet, where Pynchon allows his hippie detective Doc Sportello’s marijuana haze to infiltrate (and thus lighten) the novel’s discourse, Ellroy’s technique simply compounds and confounds in its ugliness. But don’t be mistaken–Blood’s is a thrilling book, with tightly-drawn characters doing really mean and interesting things. There’s even a sardonic sense of humor under the punchy grisliness of it all. If Pynchon’s universe propels on the paranoia of not knowing but sensing that the Powers That Be are conspiring against you, Ellroy makes it expressly clear that, yes, a sinister cabal of underworld agents are running the show. And not for the better. Even the novel’s hero Wayne Tedrow Jr. is pretty much a creep (or whatever word you want to pick for a heroin runner who kills his dad in a bid for his step mom’s affection)–but he’s a fascinating creep, and in Ellroy’s plotting, one you want to root for.

So, if you’ve had any passing interest in this book, you probably want to go ahead and pick it up. I’ll do a full, proper review when I finish it, but for now, I want to repent for my erstwhile (and unfounded) prejudices against Ellroy. Makes me wonder what other writers I’ve dismissed out of genre prejudice.

Blood’s a Rover is now available in hardback from Knopf.