☉ indicates a reread.

☆ indicates an outstanding read.

In some cases, I’ve self-plagiarized some descriptions and evaluations from my old tweets and blog posts.

Red Shift, Alan Garner ☆

Three plots, three eras, one place: Roman-conquered England, English Civil War, contemporary (early seventies) England. Great read, reminded me a bit of Hoban’s Riddley Walker.

Tyll, Daniel Kehlmann, trans. Ross Benjamin

Tyll Ulenspiegel teaches himself to walk the tightrope and becomes the greatest jester of his age, bearing witness to the horrors of the Thirty Years’ War. Very funny, slightly cruel.

The Silentiary, Antonio di Benedetto, trans. Esther Allen

In my review, I wrote that “The Silentiary is ultimately a sad, though never dour, read” that “does not wax elegaic for a romanticized, quieter past” or “call to make peace with cacophony.” The cacophony is modernity, and Di Benedetto’s sad hero does all he can to resist it. (He fails.)

Critics, Monsters, Fanatics, and Other Literary Essays, Cynthia Ozick

Moments of sharp criticism marred by “old-man-yells-at-cloud” vibes. The thematic undercurrent of the collection is the anxiety of loss of influence.

Fever Dream, Samanta Schweblin, trans. Megan McDowell

I wanted to like this novel a lot more than I did.

Cities of the Red Night, William S. Burroughs ☉☆

Burroughs’ final trilogy was a highlight of 2022 for me. I read the first book when I was far too young to understand it (not that I “understand” it now so much as feel it). The trilogy as a whole is an underrated postmodern classic, eclipsed by Burroughs’ cult of personality and weird sixties stuff. The strange beautiful ending of Cities collapses narrative into a performative verbal utopia. Has another book so accurately captured the all-at-onceness of dreams and nightmares?

I sneaked a whole thing into a blog about the rumors that Burroughs used a ghostwriter in his later years to clean up his final trilogy.

The Soft Machine, William S. Burroughs ☉☆

A reread, a kind of quick chaser while I tried to secure the next book in Burroughs’ last trilogy.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, trans. Simon Armitage

I listened to the audiobook (which included the original text) and really enjoyed it. I had intended to take it in before watching the film The Green Knight, but then I forgot to watch the film. (I still haven’t seen it.)

Moon Witch, Spider King, Marlon James

I wrote a few posts about James’s follow up to his outstanding 2020 novel Black Leopard, Red Wolf. In the last post I wrote on the novel, I concluded with “More thoughts to come” and then I never blogged about it again. After the dazzle of its predecessor, Moon Witch was a (big) disappointment—but I’ll read the next installment.

Fidelity, Grace Paley

I don’t usually just sit down and read a whole book of poetry, but that’s what happened here. Checked it out from the library and it really stuck with me—playful, sad, focused on the end of life.

Don’t Hide the Madness, William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg

A series of conversations between Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. Burroughs is getting pretty close to the end of his life here, and Ginsberg seems to want to get him to further cement a cultural legacy through a late oral autobiography. Burroughs repeatedly derails these attempts though, which is hilarious. Burroughs talks about whatever comes to mind (often his guns). Loved it

Two Slatterns and a King, Edna St. Vincent Millay

A short play. I don’t really remember it.

The Hole, Hiroko Oyamada, trans. David Boyd

From my review: “The Hole is wonderfully dull at times, as it should be. It’s layered but brittle, with notes of a freshness just gone sour. It’s a quick, propulsive read—a thriller, even, perhaps—but its thrills culminate in sad ambiguity.”

The Very Last Interview, David Shields

The Last Interview: pretentious, solipsistic, shallow, bathetic, and very readable. Hated it!

Augustus, John Williams ☆

Loved it. Fantastic stuff. A good friend recommended it and I read it, even though the premise seemed worked to death already. Nevermind—good writing is good writing.

Going to Meet the Man, James Baldwin

Not really sure how I’d only read two of the stories here before this year. Good stuff.

Harrow, Joy Williams ☆

Williams takes the “post-apocalyptic” quite literally–Harrow is about post-revelation, an uncovering, a delayed judgment from an idiot savant. It’s one of those books you immediately start again and see that what appeared to be baggy riffing was knotting so tight you couldn’t recognize it the first time through — the appropriate style for a novel that dramatizes Nietzsche’s eternal return as a mediation of preapocalyptic consciousness in a post-apocalyptic world.

Telluria, Vladimir Sorokin ☆

One of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in a long time. Telluria is a polyglossic satirical epic pieced together in vital miniatures. Its fifty sections are simultaneously discrete and porous, richly dense but also loose and funny. It teems with life and language, exploding notions of stable storytelling into a carnival of wild voices. Read it!

The Adding Machine, William S. Burroughs

A quick, lucid read and another stop-gap before I got a copy of The Place of Dead Roads.

The Place of Dead Roads, William S. Burroughs ☆

The strongest and strangest of Burroughs’ final trilogy.

The Western Lands, William S. Burroughs ☆

The weakest entry in the final trilogy; still great stuff and more electric than any contemporary sci-fi schlock out there.

Rip It Up, Kou Machida, trans. Daniel Joseph

A strange little chaser for the Burroughs trilogy, this Japanese novel is equally alienating and self-indulgent stuff, conjuring a desperate, stuffy world punctured by punkrock linguistic resistance.

The Trees, Percival Everett

A novel about racist lynchings shouldn’t really be this funny. The world of The Trees is simultaneously cartoonish and brutally realistic, its comedic overtures exploding into the awful, visceral immediacy of a history of racial violence that is not actually a history at all, but a lived reality.

A Short History of Russia, Mark Galeotti

I read this (and really enjoyed it) as I reread Sorokin’s Telluria.

Binti, Nnedi Okorafor

An interesting concept marred by awful prose. I was not the intended audience.

Revenge of the Scapegoat, Caren Beilin ☆

I can’t encapsulate this zany, cruel novel into a pithy sentence or two. Read my review if you want me to justify my sentiment that this is an excellent book.

The Deer, Dashiel Carrera

Carrera’s debut novel is sometimes brilliant, often frustrating, gloomy, surreal, and terse.

2666, Roberto Bolaño, trans. Natasha Wimmer ☉☆

My fourth full trip through 2666 was an audiobook this time. I’ll go through it again.

The Living End, Stanley Elkin

A perfect comedic chaser to the weight of 2666. The Living End, like the other novels I’ve read by Elkin, is probably best understood as a series of vaudevillian riffs—but those riffs add up to a wonderful metaphysical complaint here. Great stuff.

Prison Pit, Johnny Ryan

Abject violence and every manner of cruel depravity. Problematic! Mean! Funny stuff!

The Lonely Boxer, Michael Anthony Perri

A terse, dark (and often funny) boxing story packed with punchy sentences.

Blue Lard, Vladimir Sorokin, trans. Max Lawton ☆

I think Lawton’s translation of Blue Lard is out next year from NYRB, and I’ll wait until then to write more about it. If you were to ask me what my favorite book of 2022 is, I’d probably say, “Vladimir Sorokin’s Telluria,” but the truth is my favorite book of 2022 is Vladimir Sorokin’s Blue Lard—but that isn’t out yet.

Checkout 19, Claire-Louise Bennett ☆

I generally detest what might be termed autofiction unless it is particularly excellent, interesting, perceptive, and well-written: which proves that genre labels really don’t mean that much. Checkou 19 is particularly excellent, interesting, perceptive, and well-written, and I will continue to read whatever Bennett publishes.

Paradais, Fernanda Melchor, trans. Sophie Hughes

While Paradais is not as rich and full (and really, just long) as Melchor’s novel Hurricane Season, it’s cut from the same abject cloth. Two kids working towards becoming full-time alcoholics in an upscale development somewhere in Mexico ruin their lives. It’s a grimy glowing postmodern gothic, part of the Nothing Good Happens genre of what I think of as the Nothing Good Happens genre, reminiscent of Handke’s Funny Games, Bolaño’s myth crimes, and Nicolas Winding Refn’s neon romance terrors. Good stuff.

Minor Detail, Adania Shibli, trans. Elisabeth Jaquette

A short book in two distinct halves, extrapolating individual trauma onto the trauma of the Palestinian people as a whole. Another one I wanted to like more than I did.

Dull Margaret, Jim Broadbent and Dix

Actor Jim Broadbent made a graphic novel with the artist Dix based on Bruegel’s painting Dulle Griet—and it’s really good!

Their Four Hearts, Vladimir Sorokin, trans. Max Lawton

Vladimir Sorokin’s novel Their Four Hearts made me physically ill several times. To be clear, the previous statement is a form of praise.

Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy ☉☆

I read it or audiobook it at least once a year. I found myself falling asleep to the audiobook every night, picking it up in random places.

A Shock, Keith Ridgway ☆

The rondel of stories in A Shock coalesce into a novel that captures the weird energy of consciousness butting up against concrete reality. Standout story “The Sweat” ends with a three page monologue that begins “Happiness is lovely to come across.” Probably one of the best passages I read all year.

The Setting Sun, Osamu Dazai, trans. Donald Keene

Another book I wanted to like more than I actually did.

Players, Don DeLillo

DeLillo’s early novel reads like a dress rehearsal for the midperiod stuff (particularly The Names, Libra, and Mao II). A novel of boredom, transience, games and their players.

Fireworks, Angela Carter

If the pieces here are not as refined and unified as the anti-fairy tales that comprise Carter’s more-celebrated collection The Bloody Chamber, they are all the more fascinating as studies in sadomasochism, alienation, and the emerging of a new literary consciousness.

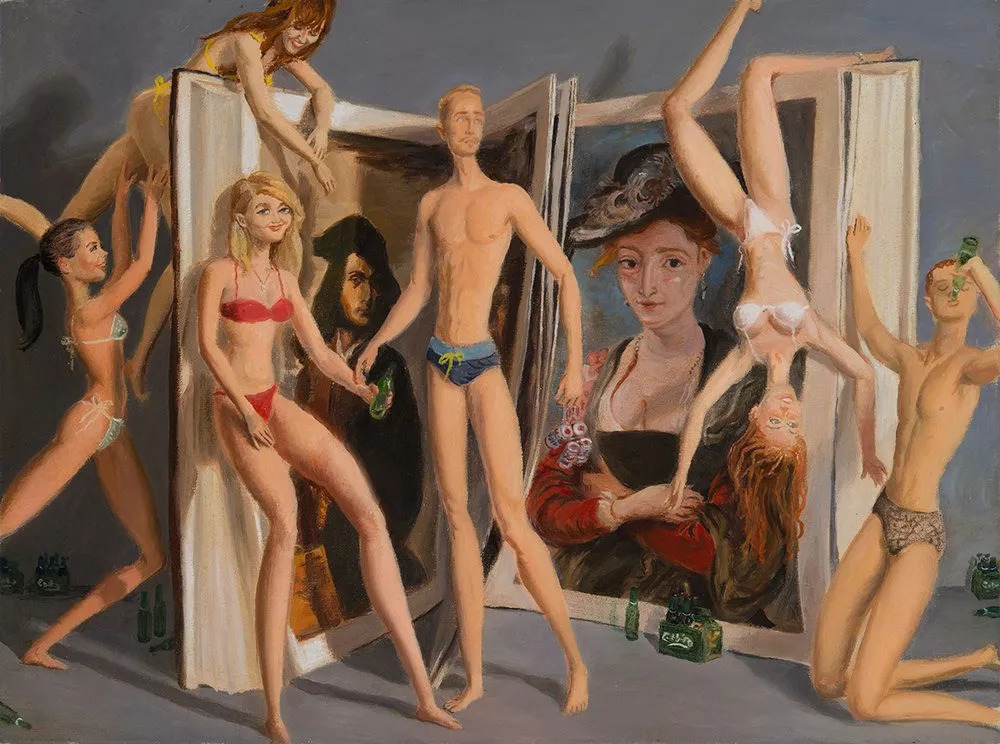

Tripticks, Ann Quin ☆

Quin’s fourth and final novel (in print again for the first time in two decades, thanks to And Other Stories) is a radical satire of America. It’s a road novel and an anti-road novel, elegant and messy, sexy and ugly, cruel and generous. The narrative plays out in a cartoonish, slapdash sequences of chases across the American West—the narrator is either chasing one of his ex-wives and her new lover, or is being chased by them. Flashbacks interject without transition or any other warning, treating us to grotesque cavalcade of characters, including the ex-wife’s father and mother (the father is a particularly wonderful satire of the American self-made noveau riche blowhard) and a sex cult leader. Quin also slices in lists that start somewhat orderly and then explode into hyperbole and/or bathos. The germ of Tripticks was first published in the J.G. Ballard and Martin Bax’s seminal journal Ambit as part of a contest. The gimmick was to write a story Under the Influence of Drugs. Quin won with her story, composed under the influence of the contraceptive pill.

My Phantoms, Gwendoline Riley

An unhappy novel about an unhappy family. Saw way too much of myself in this one.

Cardinal Numbers, Hob Broun ☆

I feel as if Cardinal Numbers were written specifically for me. Hob Broun’s shorts (not stories, not tales) are like an intersection of Barry Hannah and David Berman—funny, devastating, enigmatic, thoughtful. Cardinal Numbers is the best collection of short stories that no one has ever heard of.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John le Carre ☆

Fun fun fun fun fun sad fun fun fun fun dark fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun fun dark fun fun fun fun fun bit weird fun fun fun fun fun fun more fun fun fun fun

The Passenger, Cormac McCarthy ☆

I riffed a lot on McCarthy’s baggy opus and read exactly one review of it (Joy Williams’), but I was still attuned to enough chatter to get the impression that many people did not like The Passenger. My take is something like: The Passenger is McCarthy’s messy, sad, joyful synthesis of McCarthy’s oeuvre. If Suttree is his attempt to synthesize the American literature before it into something new (which it is), McCarthy’s last (?) big novel does the same—but for McCarthy’s books. I tried to get at that idea in some of my riffs on the book. But I’ll understand too if folks wanted Something Else from The Passenger. I loved it.

All the Pretty Horses, Cormac McCarthy ☉☆

I read it again for the first time in years as a kind of comedown from The Passenger as I waited for Stella Maris to drop. I’ll read the other Border Trilogy books next year.

First Love, Gwendoline Riley

A slim, spare, precise study of passive-aggressive cruelty, sublimated dreams, and lowered expectations. Pervading the novel is a general sense that one would prefer not to get stuck in a corner with any of these characters at a party, let alone end up living with one. I think Gwendoline Riley is a good writer but I don’t think I’ll read anymore Riley novels.

Hello America, J.G. Ballard

You’d think a novel where President Manson wants to make America great Again would feel more prescient, but Ballard’s so in love here with the sparkle and pop of Pop Art America that he fails to attend to the dirt, grease, and grime that make the machine run. A fun novel, but its contemporary currency is squashed not so much by historical reality as the weight of Ballard’s oeuvre before it.

Cinema Speculation, Quentin Tarantino

A messy book about a messy decade of filmmaking. Tarantino names a bajillion films in Cinema Speculation and makes me want to watch almost all of them. Some of his recommendations fall short of his praise (Joe) while others exceed it (Hi, Mom! and Rolling Thunder). This book almost reads like an elegy to moviegoing as a communal experience that will never come back.

Monsters, Barry Windsor-Smith ☆

When I was a kid, Barry Windsor-Smith’s Weapon X was a revelation to me, one which (perhaps ironically, as it was a Marvel comic book featuring mainstream comics’ most popular character) led me away from Marvel and DC comics into alternative stuff. When I saw Monsters on the shelf of my college library, I immediately checked it out, a little bit confused that I simply had never heard of something so big and beautiful. When I started the novel, I was a bit worried that it was simply a retooling of the Weapon X material (itself a retooling of Shelley’s Frankenstein)—but that isn’t the case. Sweeping, dense, sad, and occasionally unexpectedly funny, Monsters is Windsor-Smith’s masterpiece, a word I don’t use lightly.

Stella Maris, Cormac McCarthy

Above, I claimed that The Passenger is McCarthy’s self-synthesis of his own oeuvre. Stella Maris is the incestuous sibling of that novel, one that has to be read intertextually against it/with it—a call to read these last (?) works with/against the McCarthy novels that preceded them.

Dr. No, Percival Everett

While I was reading Stella Maris a second time, I started Everett’s Dr. No on audiobook. This was at the suggestion of Hoopla, the service my library uses. I knew that Dr. No was Everett’s new novel, and that was about it. I didn’t know that it was about a mathematician who studies nothing. It would be hard to overstate the overlap between Dr. No and Stella Maris (hell, the female protagonist in Everett’s novel is a topologist!), but they couldn’t be more tonally different. One of my favorite gags in Dr. No is the naming of characters—Everett gives characters names like “Stephanie Meyer,” “George Bush,” and “Otis Redding.” And while this initially seems like a (perhaps-lazy) postmodern joke, it ends up paying dividends in the novel’s central themes of nothing butting up against the prospect of naming nothing.

At the Doors and Other Stories, Boris Pilnyak, trans. Emily Laskin, Isaac Zisman, Louis Lozowick, Sofia Himmel, John Cournos

A lovely little book by a Russian author I’d never heard of. The title story “At the Doors” reminds me very much of “Mondaugen’s Story” in Pynchon’s V.—a strange mix of terror, grime, and zaniness that resists neat coherence. Good stuff!