Where to start, where to start…

Do I say that the book is good, great, fantastic, a literary achievement? These words don’t seem big enough, or they seem like hackneyed clichés, ugly inadequacies. Here’s a very short review: go get the book and read it. Worried that 900 pages is too long? Don’t worry. They fly by. I read the book in less than a month, usually in forty or fifty page sittings, something I usually don’t make time to do. But hang on, I’m already off to a bad start I admit, there’s no context here, is there? Let me try again.

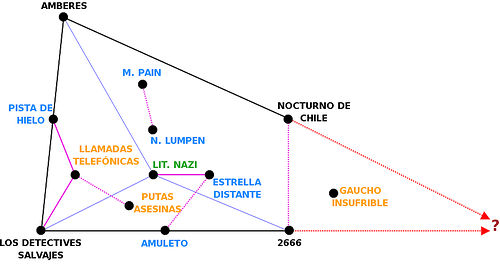

2666 is Chilean exile Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous magnum opus. The book comprises five sections, each focusing on a separate but often overlapping set of characters and locations. The book is, in my paperback edition (composed of three separate books) 893 pages long. The book is excellent, addictive, full of pain and pathos and humanity. Most of the sentences are very, very long. What is it about, then? There are too many answers to that question, but here goes–

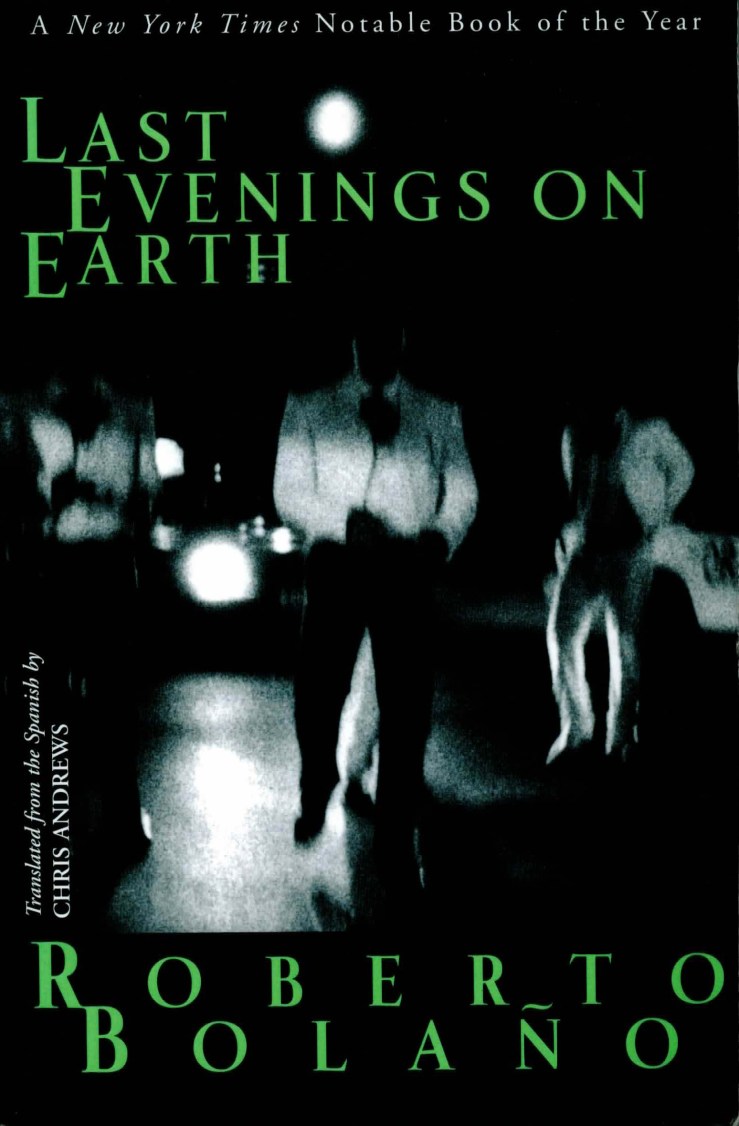

There are two major, intertwined plot threads in 2666, one about a series of gruesome rapes and murders in the fictional city of Santa Teresa, Mexico, and the other concerning an obscure German writer with the improbable name Benno Von Archimboldi. These two threads weave through the labyrinth that is 2666, connecting the many themes and tropes and moods and tones of this massive novel. Bolaño’s styles shift and weave and morph throughout the book, evoking laughter and rage and pity and anticipation and overwhelming sadness. He’s very often philosophical but never abstract, lyrical but grounded, and always entertaining. Bolaño’s command of thousands of different voices is on display here, whether he’s telling the tale of an ex-Black Panther or an exiled Russian sci-fi writer, a Romanian general or a crippled Italian critic. Bolaño’s voices layer upon each other in a strange chorus; often I found myself shocked at how, 300 pages later, a different character in a different place and time will hit on the same note–a comment about semblances and reality, or graveyards, or fate and chance and choice, or mirrors, or dreams and nightmares, or giants, or insane asylums, or aliases and pseudonyms–only this new character will express this note in a new or different tone, adding to the richness and dazzling complexity of the tale. Bolaño’s voices are often framed in a series of tales like Russian nesting dolls, only, where a writer like John Barth might explicitly announce or call attention to this device, Bolaño’s storytelling has a humanistic, natural quality, a quality that provokes and calls attention to the limits of human memory and our collective capabilities to narrativize our lives. But hang on again, I’ve gotten away from plot summary, haven’t I? Do you really need a summary? Yes? Will, “It’s about everything. Life, death, all that shit,” will that not do? Okay. Another attempt, then.

The first section of 2666, “The Part About The Critics,” tells the story of four critics from four European countries who specialize in Archimboldi; in fact, two of the critics pretty much invent Archimboldi studies. Through their critical endeavors, the obscure, unphotographed writer rises to greater prominence. The four set out to find him, initiating the novel’s detective lit thread. They wind up in Santa Teresa, a city experiencing a seemingly endless slew of murders. In Santa Teresa, they meet a Chilean professor named Amalfitano, who (obviously) features heavily in the next section, “The Part About Amalfitano.” At this point, we start discover more about the unsolved rapes and murders of young women in Santa Teresa, but these crimes linger in the background, the story of Amalfitano, his ex-wife, his daughter, and a geometry book hanging from a clothes line at the fore. Amalfitano’s teenage daughter returns in the third section, “The Part About Fate.” This part of the novel details Oscar Fate, an African-American reporter who travels to Santa Teresa to cover a boxing match only a few days after the death of his mother. “The Part About Fate” builds to a rapid, grotesque, nightmarish climax, where the journalist, alien and impartial visitor, silent observer, becomes implicated in the ugly violence and grim desperation of Santa Teresa. This rhetorical move leads the reader into the longest section of 2666, “The Part About The Crimes,” in which we finally learn about the gruesome murders–hundreds and hundreds of murders–of the young women who work in the factories of Santa Teresa. The final section, “The Part About Archimboldi,” works as a partial bildungsroman, revealing the life story of the man who becomes Benno von Archimboldi. But does “The Part About Archimboldi” wrap up all the riddles, seal the deal, lead us out of the labyrinth and into the light–do we get answers? Let’s see–

Readers enthralled by the murder-mystery aspects of the novel, particularly the throbbing detective beat of “The Part About The Crimes,” may find themselves disappointed by the seemingly ambiguous or inconclusive or open-ended ending(s) of 2666. While the final moments of “The Part About Archimboldi” dramatically tie directly into the “Crimes” and “Fate” sections, they hardly provide the types of conclusive, definitive answers that many readers demand. However, I think that the ending is perfect, and that far from providing no answers, the novel is larded with answers, bursting at the seams with answers, too many answers to swallow and digest in one sitting. Like a promising, strangely familiar turn in the labyrinth, the last page of the book invites the reader back to another, previously visited corridor, a hidden passage perhaps, a thread now charged with new importance. Like Ulysses or Moby-Dick or Infinite Jest before it–and yes, yes, I would class this book with those without batting an eye–2666 is a book that demands multiple readings. Fortunately, despite its grim subject, it’s endlessly entertaining, rich with literally hundreds and hundreds of stories, stories that impel and compel you to read, read, read. But, again like Ulysses or Moby-Dick or Infinite Jest before it, 2666 is not for everyone.

I’ll quote from the only negative review at Amazon right now, by one Mr. Nathan King, who writes, “This is not an enjoyable/pleasurable book to read. . . . this book is a GRUESOME and HORRIFICALLY VIOLENT book. The largest section of the book is basically 300+ pages of autopsy reports. You will read the words “vaginally and anally raped” over and over and over, until it runs through your mind day and night.” King’s review is accurate in several ways, although I fundamentally disagree with his overall assessment, of course. The book’s violence will run through your mind day and night: the book is awfully affecting. One of Bolaño’s missions in the book, it seems, is to continually press on the reader a horrific assemblage of dead, raped, mutilated bodies, bodies found in Dumpsters, trash heaps, ditches, alleys; violated, nameless, unclaimed bodies. While “The Part About The Crimes ” clearly contains most of these horrors, disposable bodies litter the entire book, whether they are Jews to be executed by Nazis in WWII or young men murdered in prison while the wardens watch. Bolaño’s method then is to confront his readers with all these unsolved, perhaps unsolvable crimes, and ask how one can witness to the horrors of life without giving in to despair or madness or suicide. Callous or cynical readers, looking for a simple answer to “Whodunnit?” will miss the multiplicity of answers that Bolaño provides, which might be boiled to: We all did it. We are all responsible for these crimes.

At many points throughout the massive tome Bolaño addresses this central problem, but this passage from “The Part About Amalfitano” sums up one possible solution quite beautifully. Amalfitano, slowly going insane, wondering about existence and movement and sleep and reality, thinks–

Anyway, these ideas or feelings or ramblings had their satisfactions. They turned the pain of others into memories of one’s own. They turned pain, which is natural, enduring, and eternally triumphant, into personal memory, which is human, brief, and eternally elusive. They turned a brutal story of injustice and abuse, an incoherent howl with no beginning or end, into a neatly structured story in which suicide was always held out as a possibility. They turned flight into freedom, even if freedom meant no more than the perpetuation of flight. They turned chaos into order, even if it was at the cost of what is commonly known as sanity.

To systematize, to narrativize then, to try to put order and meaning into one’s life, or the lives around you, to witness to others’ pain by claiming it as your own, these moves then betray one’s ability to accurately, or sanely, perceive the world. It’s this great cost that Bolaño navigates in 2666, and he does so with aplomb and precision and grace.

Have I still not convinced you to read 2666? I could keep going and going, on and on, and I won’t be the only one–Bolaño’s book will be one for posterity, a great work that literary critics (much like the ones he sympathetically parodies and valorizes here) will debate over, ponder over, discuss, write about, love, and be tortured by for ages to come. At the same time, this is not a book that one should feel is only for the “literary élite” (whatever that means)–with its force and vitality and inventiveness, with its rich, detailed dream/nightmare world, 2666 is a book that you, dear reader, should read, must read. Very highly recommended.