Dennis Johnson, along with wife Valerie Merians, heads Melville House Publishing, an independent book house putting out some of the best stuff on the market today. They also have a bookstore in Brooklyn that regularly hosts all kinds of neat literary-type events. Melville House is the outgrowth of Johnson’s literary blog MobyLives, an insightful source of reportage on the literary world today. In 2007, the Association of American Publishers awarded Melville House the Miriam Bass Award for Creativity in Independent Publishing and in 2009 The Village Voice declared Melville House “The Best Small Press of the Year.” I talked to Johnson by phone last week and he answered my questions with patience and humor. We discussed how Johnson finds the marvelous books he publishes, translation, novellas, and upcoming releases from Melville House. After the interview he was kind enough to ask me about my own blog and offer me some encouraging words. Just a few days after our talk it was announced that one of Melville House’s recent publications, The Confessions of Noa Weber by Gail Hareven had won the 2010 Best Translated Book Award for fiction.

Biblioklept: I want to begin by congratulating Melville House on Hans Fallada’s novel, Every Man Dies Alone. It’s done really well both critically and commercially. The book is something of a “recovered classic,” published just last year for the first time in English. Can you tell us a little bit about how Melville House came to publish the book?

Dennis Johnson: Well, it was a search it’s a real saga about hunting down that book. I’m always interested in finding material from that part of the world and that time of history because I think a good deal of very good literature was lost between the two wars. And it’s just writing that I like a lot. So a friend of mine, the fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg had family that came through that part of the world at that time and I asked her if she had any recommendations and she told me I should look into Hans Fallada, who I’d never heard of. So I tracked down a couple of his titles that had been translated–because he was a bestselling writer here in the 1930s–and it took a while but I found some of those books which had been out of print for a long time and I really loved them. And then, von Furstenberg told me that his best one had never been translated. That was Every Man Dies Alone. And so we set about going after it and acquiring it. And, at that point, once we’d discovered it, it was pretty easy sailing. But tracking down his stuff that had been translated and finding out more about him was really kind of a fun bit of detective work.

B: Did Michael Hoffman translate it specifically for Melville House?

DJ: Yeah, he did. We hired him to do it.

B: Is that normally how you go about with these works–like Nanni Balestrini’s Sandokan or Imre Kertész’s The Union Jack? Hiring a translator?

DJ: Well, there’s a couple of things you can do. You can find the translator, or you can reprint things that have been translated already, if you think it’s already a good translation–that’s a less expensive way to do a translated book. So for example, with the Fallada, I bought some old translations of his other books and published them simultaneously with the new translation of Every Man. There was, you know, there was no old translation to buy. But two of his other books, two great books, one called The Drinker and one called Little Man, What Now? I thought were pretty well translated so we just bought those old translations. They were out of print, they were available [for publication].

B: It seems like a lot of the books you guys put out are–I don’t know how to put it–recovered classics or cult books or just books that English-reading audiences just aren’t necessarily exposed to. Is that purposeful with Melville House?

DJ: I think we have a fairly mixed list. The names you were citing a minute ago . . . Balestrini, he’s only been translated once, I think, thirty or forty years ago. But he’s a very prominent writer in Italy. And it wasn’t exactly a “discovery,” it was just someone that we thought American audiences should know about. Imre Kertész on the other hand is extremely famous, he’s a Nobel Prize winner and he’s published by Knopf. We were thrilled when he wanted to come to Melville House. So, you know, some of these writers are here, some are not. We publish some well known writers, some very obscure writers. We try to mix it up. You know, there’ s no rule, just good literature.

B: Can you talk a little bit about the Contemporary Art of the Novella series? How did it come about?

DJ: Well, we originally had a series called just the Art of the Novella. It’s classics, many of them translated, classics from around the world, lots of European classics, and some of those are new translations that we did it, some are old translations that we reprinted. And that series did really, really well and people really seemed to love it so we decided that we would do a contemporary version of that series and try to mix it up the same way. And so the new series has new discoveries in it, some old reprints, things from around the world, we’re expanding beyond Europe and Russia, we’ve got a native Japanese author named Banana Yoshimoto in it coming out, we’ve got African writers, South American writers . . . It’s been off to a very good launch. I think we’ve done about fourteen or fifteen books in that series so far and it’s going really well. You know, it’s very hard to publish translation in the United States. It doesn’t . . . it doesn’t sell. It’s hard to keep it in store for a long time. And it’s expensive to do translated books because you have to pay your translator. In the Contemporary series we often use new translations because it’s new work that’s never been translated before and that can get very expensive because you’ve got two authors, you know, you have to pay the author, the translator, and that’s why a lot of people are cutting back on doing translations. But we wanted to keep doing translations and we had to figure out a way to keep doing it and one idea we had was, if we had this series of short novels . . . well, one, they’re just cheaper to do, they cost less to buy from another publisher, they cost less to make because they’re less paper and they cost less to translate because they’re shorter. And you know, you pay by how long. So, it suddenly became a more economical way for us to publish translated books. The booksellers, they like the Contemporary series. They get the whole series and they keep it in the store. So, for example, we’re about to do a deal with a new book store in Fort Greene called Greenlight where they would do a whole wall of these books. Other stores do a spin-rack of these books. And they just keep them. And what usually happens with new books is you just get a few weeks in the bookstore and if it doesn’t sell they return it. And so we would get really creamed on the translated work because it wouldn’t have very long in the store and it’s hard to get publicity for them and then they just didn’t have enough time to sell. But, if they’re taking the whole series and keeping them on display, forever, well, then these books have a real chance of surviving. So there were a lot of good reasons for us to do a Contemporary series. And in the end, the reason was that it allowed us to keep doing really good, serious, translated work.

B: What do you think about “rock star” writers like Haruki Murakami and Roberto Bolaño whose English translations sell very well? Does that help the prospects of translated books at all?

DJ: Well, every year there are one or two books that are translated that do very well. But they’re the exception to the rule. At any given point in the year, you look at the New York Times bestseller list for fiction, there’s almost never a translated book on it. Or if there is, it’s some, you know, Scandinavian murder mystery or something. It’s very rare it’s a serious work of literature. So I would say those writers are the exception to the rule. But it’s certainly does help those of us selling translated fiction to be able to point to those things. It encourages booksellers to give us a chance.

B: Can you tell us a little bit about upcoming titles and authors you’re excited about?

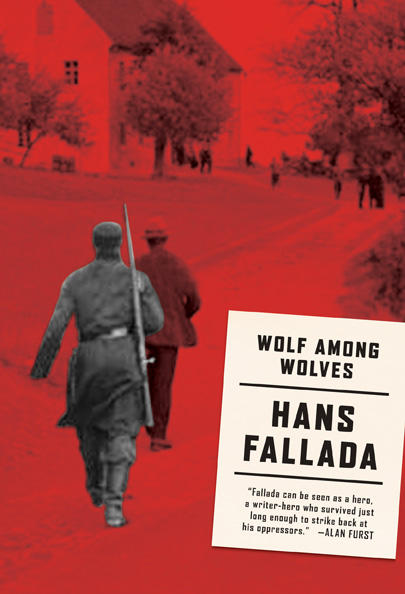

DJ: Well, we’re doing another Fallada–

B: Wolf Among Wolves, right?

DJ: We’re doing Wolf among Wolves in May. And we’re doing the paperback for Every Man Dies Alone at the end of this month, as a matter of fact. So those are two that I’m really excited about. We have some really great nonfiction coming out. We just published a book about North Korea called The Cleanest Race. It’s about understanding North Korea through its propaganda. It’s got a lot of really wild art showing the propaganda posters and movie stills and things. And then we’ve got some novels coming out, one from a young British writer named Lee Rourke. It’s the first novel. It’s called The Canal and I think it’s one of the very best novels we’ve ever published. It’s generating a lot of excitement. We’re doing another one with Kertész next year, which is a big novel called Fiasco. He wrote a trilogy years ago about his experience in the camps. What was he, fifteen or something, when he was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, working in a Nazi factory trying to turn coal into gasoline? And he wrote a novel called Fatelessness about that and another one called Kaddish for an Unborn Child. And Knopf published Kaddish and Fatelessness but they never published Fiasco. So we’re really excited about that.

B: Something I enjoy about MobyLives is your perspective as a publisher covering real news about book selling.

DJ: Thanks. It’s a labor of love. If you look at the historic arc of the website, you can see that we became more informed by being a publisher. I wasn’t a publisher when I started it and it was much more general-interest reader kind of thing. I try to get help. I try to make the staff here participate, I think it makes it a little more wide-ranging.

B: So, have you ever stolen a book?

DJ: Sure, yeah. I used to steal a lot of books from my brother. I remember stealing Gore Vidal’s Burr. My big brother’s a lot older than me and he left the house when I was a kid and I remember stealing a lot of his books. So Burr yeah, a novel Vidal wrote about Aaron Burr. Fantastic book. I still have it. He hasn’t asked for it back. I don’t think he knows.

On the heels of last year’s hugely successful first-time-in-English publication of Every Man Dies Alone, the good folks at Melville House have issued another of Hans Fallada’s epic novels,

On the heels of last year’s hugely successful first-time-in-English publication of Every Man Dies Alone, the good folks at Melville House have issued another of Hans Fallada’s epic novels,

This weekend, I read and thoroughly enjoyed the first volume of Adam Thirlwell’s The Delighted States (new in a handsome trade paperback edition from

This weekend, I read and thoroughly enjoyed the first volume of Adam Thirlwell’s The Delighted States (new in a handsome trade paperback edition from  On that book specifically (and Bolaño’s work in general)–

On that book specifically (and Bolaño’s work in general)–