News that J.J. Abrams will direct the seventh Star Wars film almost broke the internet yesterday. It’s easy to see why anyone who nerds out over franchise properties would take interest. After all, Abrams helmed the 2009 big-screen reboot of Star Trek, a film that shook the camp and cheese from the franchise’s previous films, replacing it with hip humor, thrilling action, and lots and lots of lens flare. Abrams’s sequel, Star Trek Into Darkness is perhaps the most anticipated franchise film of the year.

I won’t speculate whether an Abrams Star Wars film will be successful or not—you probably wouldn’t want me to, because I hold the extreme minority opinion that Lucas’s Revenge of the Sith is a deeply profound and moving work of cinema art—but I do think that the choice to hand the next big film in the Star Wars franchise over to Abrams represents the worst in corporate thinking. This goes beyond the playground logic of Abrams swiping all the marbles—he gets both the “Star” franchises!—what it really points to is the bland, safe commercial mindset that guides the corporations who own these franchises. J.J. Abrams is a safe bet. I can more or less already imagine the movie he’ll make.

Star Wars: A New Hope came out in 1977, perhaps at the exact moment that the innovations of the “New Hollywood” movement crested (before Heaven’s Gate crashed the whole damn thing in 1980). The films of this decade—Badlands, The Godfather films, Bonnie & Clyde, Chinatown, Nashville, Dr. Strangelove, etc.—helped to redefine film as art; they also captured and illustrated a zeitgeist that’s almost impossible to define. And while plenty of filmmakers today continue in this spirit, their films are often pushed into the margins. The Hollywood studio system is tangled up in big budget spectacle. I have no problem with this, but at the same time I think that there’s something sad in it all—in the bland safety of having Abrams turn out Star Wars and Star Trek films—it all points to a beige homogeneity.

The problem I’m talking about is neatly summed up by Gus Van Sant in a 2008 interview with The Believer:

So, there were some projects I never really could get going, and one of them was Psycho. It was a project that I suggested earlier in the ’90s. It was the first time that I was able to actually do what I suggested. And the reason that I suggested Psycho to them was partly the artistic appropriation side, but it was also partly because I had been in the business long enough that I was aware of certain executives’ desires. The most interesting films that studios want to be making are sequels. They would rather make sequels than make the originals, which is always a kind of a funny Catch-22.

They have to make Bourne Identity before they make Bourne Ultimatum. They don’t really want to make Bourne Identity because it’s a trial thing. But they really want to make Bourne Ultimatum. So it was an idea I had—you know, why don’t you guys just start remaking your hits.

Lately it seems that the studios trip over themselves to reboot their franchises—the latest Spider-Man film (the one you probably forgot existed) being a choice example of corporate venality. In a way, it’s fascinating that Sam Raimi, something of an outsider director, was allowed to do the first Spider-Man films at all. Of course, now and then a franchise film (or potential franchise film) winds up in the hands of an auteur—take Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, for example. Alfonso Cuarón’s third entry in the franchise can stand on its own (it certainly saved the franchise from the tepid visions of Chris Columbus). Even stranger, take Paul Verhoeven’s films RoboCop and Starship Troopers. These films were brilliant subversive satires, and what did Hollywood do to the movies that came after them? These franchises devolved into flavorless, flawed, run of the mill muck.

Of course, entertainment conglomerates have good (economic) reasons to “protect” their product. David Lynch’s Dune remains one of the great cautionary tales in recent cinema history. What could have reinvigorated “New Hollywood” instead proved a disastrous flop. Dune never panned out as the blockbuster franchise that it could have been; instead, it gets to hang out in a strange limbo, greeting newer arrivals like Chris Weitz’s atrocious adaptation of The Golden Compass and Andrew Stanton’s underrated John Carter from Mars. It’s actually sort of surreal that we even got a Dune film by David Lynch, complete with Kyle MacLachlan, Brad Dourif, Jack Nance, and fucking Sting.

What’s even weirder is that Alejandro Jodorowsky tried to adapt Dune, working with artists H.R. Geiger and Moebius. (Jodorowsky also planned to involve Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, and Karlheinz Stockhausen among others in the film). What a Jodorowsky Dune film might have looked like is a constant source of frustrated fun for film buffs.

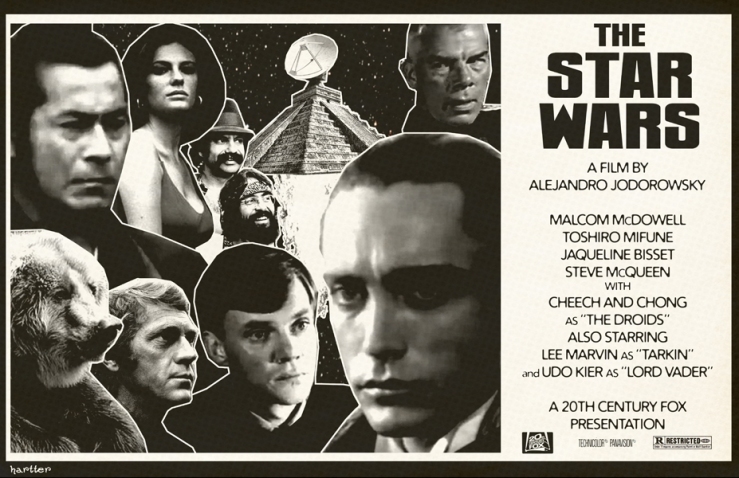

But what about a Star Wars film by Jodorowsky? What might that look like?

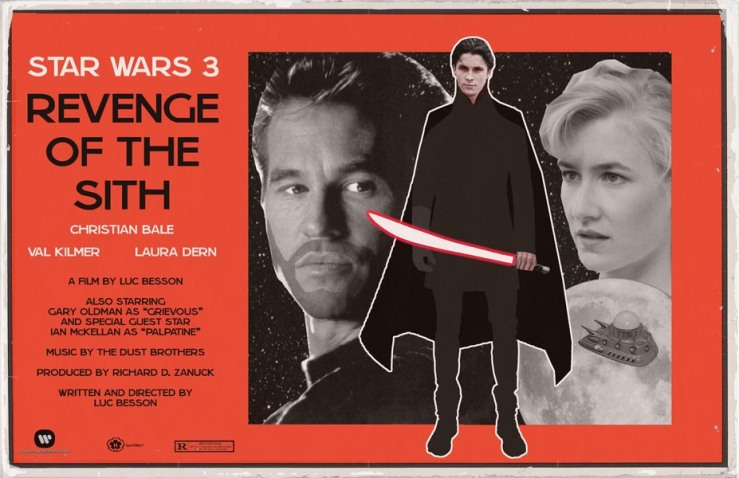

Sean Hartter imagines such prospects in his marvelous posters for films from an alternative universe. Hartter’s posters—most of which include not just cast and director but also specific studios, producers, and soundtrack composers and musicians—conjure up wonderful could-have-beens. They posit the kind of daring spirit and experimentalism I’d like to see more of from Hollywood franchises.

Most Hollywood franchises revere the illusion of stability in the property—the idea of a constancy of character throughout film to film. Even a franchise like the James Bond films, with its ever-rotating leads, tries to create the guise of a stable aesthetic along with narrative continuity. I would love to see something closer to the Alien franchise, the only line of films I can think of where each film bears the distinctive mark of its respective filmmaker; even if I don’t think Fincher’s Alien 3 is a particularly good film, at least it feels and looks and sounds like a Fincher film and not a weak approximation of a Cameron blockbuster or a stock repetition of Scott’s space horror (and Jeunet’s Resurrection—how weird is that one!).

But back to Bond for a moment—wouldn’t it be great to see Wes Anderson do James Bond, but as a Wes Anderson film? Or Werner Herzog? Or Cronenberg? What would Jane Campion do with Bond? (I’m tempted to add Jim Jarmusch, but he already made an excellent James Bond film called The Limits of Control). I’d love to see a range of auteur versions of the franchise. (Similarly, I’ve recently been fascinated by the way certain cult artists render major corporate franchise characters, like Dave Sim doing Iron Man, or Moebius doing Spider-Man, or Jaime Hernandez doing Wonder Woman). Obviously this fantasy will never happen—the auteur would have to have complete control—a Coen brothers’ Bond film would have to be first and foremost a Coen brothers film, not a 007 film—but hey, just like with Hartter’s posters, it’s fun to pretend.

Imagine a year of James Bond movies, one a month, featuring different directors, actors, studios, production designs. 007 films from Spike Lee, Tarantino, Almodavar, Lynne Ramsay, Lynch, Wong Kar Wai.

What would a Wong Kar Wai James Bond film look like?

What would a Wong Kar Wai Star Wars film look like?

I don’t know. I imagine it would be beautiful and moody and at times impressionistic. I imagine its narrative would tend toward obliqueness. I imagine it might infuriate die-hard fans (I imagine this last part with a big grin). I imagine that it would easily be the most human Star Wars film.

But beyond that, it’s hard to imagine what a Wong Kar Wai Star Wars film might look and sound and feel like because his films are powerful and moving and evoke the kind of imaginative capacity that marks great art, great original and originating art. Put another way, I can’t really imagine what a Wong Kar Wai Star Wars film would look like—which is precisely why I’d love to see one.

The Royal Stuarts by Allan Massie is new in paperback from Macmillan. Here’s the Kirkus review:

The Royal Stuarts by Allan Massie is new in paperback from Macmillan. Here’s the Kirkus review: