4. Decapitation by irate opera singer. Cormac McCarthy, who far surpasses even Faulkner in the mayhem he visits upon literary mules (see #s 5, 6, 7, 9, 14, 15), includes in his recent novel The Crossing (1994) the following dialogue about a mule whose recalcitrance proves insufferable to the artistic temperament of a singer assigned to tend him in a road company:

What was it he done to the mule?

He tried to cut off the head with a machete. . . .

I wouldn’t have thought you could cut off a mule’s head with a machete.

Of course not. Only a drunken fool would attempt such a feat. When the hacking availed not he began to saw. . . .

What happened to the mule?

The mule? The mule died. Of course

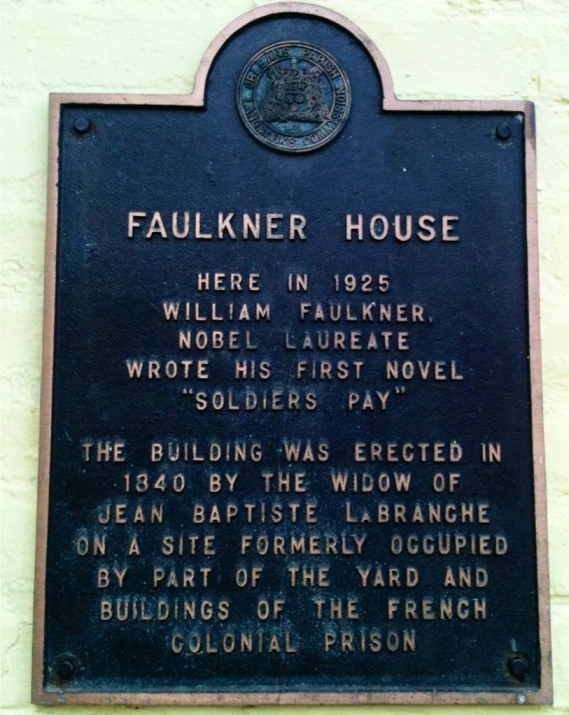

5. Drowning. This is Faulkner’s most commonly employed means of dispatch for the mules in his works. In the flood scenes he renders so effectively, we inevitably find drowned mules floating down river. As opposed to the train-struck animals in “Mule in the Yard” (see # 3), which are instrumental in developing motive and plot, Faulkner’s drowned mules tend to fall into the decorative or ornamental category, employed chiefly for drama, mood, and atmosphere. In As I Lay Dying (1930), for example, Darl recreates a wagon disaster in the surging stream: “Between two hills I see the mules once more. They roll up out of the water in succession, turning completely over, their legs stiffly extended as when they had lost contact with the earth”. In the “Old Man” sections of The Wild Palms (1939), the flood throws forth its “charging welter of dead cows and mules and outhouses and cabins and hencoops,” and Faulkner’s prose strikes an elegiac note as the convict’s skiff rides “even upon the backs of the mules as though even in death they were not to escape that burden-bearing doom with which their eunuch race was cursed”. Before the ordeal ends, the accumulation of mule carcasses reaches almost cosmic proportions as the stranded convict remembers “that other wave, the second wall of water full of houses and dead mules building up behind him in the swamp”.

Robert Morgan’s story “Poinsett’s Bridge” (1989) picks up the drowned mule topos in distinctly Faulknerian terms: “The body of a mule shot by in the current, and then a chicken coop”; but Cormac McCarthy (see #s 4, 6, 7, 9, 14, 15) varies it in Blood Meridian (1985) by having a mule drowned intentionally: “The Yumas were swimming the few sorry mules . . . across the river. . . . Downriver they’d drowned one of the animals and towed it ashore to be butchered”. (On recurrent uses of mules as culinary items see # 14.)

That the image of the drowned mule also occupies a subliterary folk status in the South is perhaps attested by a common simile in which a wealthy person is said to have “enough money to burn up a wet mule.”

6. Falls from cliffs. The novel Blood Meridian (1985) establishes Cormac McCarthy as unchallenged king of literary mule carnage. No fewer than fifty-nine specific mules die in the book, plus dozens more that are alluded to in groups and bunches. Mules are shot, roasted, drowned, knifed, and slain by thirst; but the largest number, 50 out of a conducta of 122 mules carrying quicksilver for mining, plummet from a single cliff during an ambush, performing an almost choreographic display of motion and color, “the animals dropping silently as martyrs, turning sedately in the empty air and exploding on the rocks below in startling bursts of blood and silver as the flasks broke open and the mercury loomed wobbling in the air in great sheets and lobes and small trembling satellites. . . . Half a hundred mules had been ridden off the escarpment”. (See also #s 4, 5, 7, 9, 14, 15.)

. . .

7. Fall into subterranean cavity. Near the conclusion of Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God (1973), “Arthur Ogle was plowing an upland field one evening when the plow was snatched from his hands. He looked in time to see his span of mules disappear into the earth taking the plow with them” (195). These doomed mules qualify as highly functional in the story, since a search for their bodies leads to the discovery of a number of human corpses stored in the caves underground for sexual use by the necrophiliac Lester Ballard. (See also #s 4, 5, 6, 9, 14, 15.)

. . .

9. Gunshot wounds. The high quotient of gunplay in southern fiction quite naturally extends to some of the mules that grace its pages. . . .

Mules absorb lead throughout much of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (1985), one providing a shield against incoming fire: “He . . . crouched under the ribs of a dead mule and recharged the pistol”.

. . .

14. Stab wounds. . . .

But mules are consumed readily by man, beast, and fowl in Cormac McCarthy‘s Blood Meridian (1985), and a character in Bernice Kelly Harris’s Purslane (1939) finds the practice a perfectly acceptable topic for mealtime conversation: “Uncle Millard near the foot of the table was telling about the Christmas dinner he ate in the pesthouse years ago, declaring it was fried dog and mouse stew with a slice of boiled mule”.

15. Thirst. Alkali flats in Cormac McCarthy‘s Blood Meridian (1985) yield no shortage of “the black and desiccated shapes of horses and mules. . . . These parched beasts had died with their necks stretched in agony in the sand”

. . .

18. Submersion in domestic metaphor. Once again, Cormac McCarthy creates an exclusive category (see # 4) with a scene in Cities of the Plain (1998):

When he turned around Billy [Parham] was standing in the doorway watching him [John Grady Cole].

This the honeymoon suite? he said.

You’re lookin at it.

He leaned in the doorframe and took his cigarettes from his shirtpocket and shucked one out and lit it.

The only thing you ain’t got here is a dead mule in the floor.