I can’t seem to muster language lately, to make the words do what I want them to do.

I’ve read a number of excellent (or really good) books in the past few months and haven’t been able to write more than the first few sentences of an ostensible “review” before giving up…mostly because those first few sentences usually resemble the kind of boring moaning dithering whining I’m doing now.

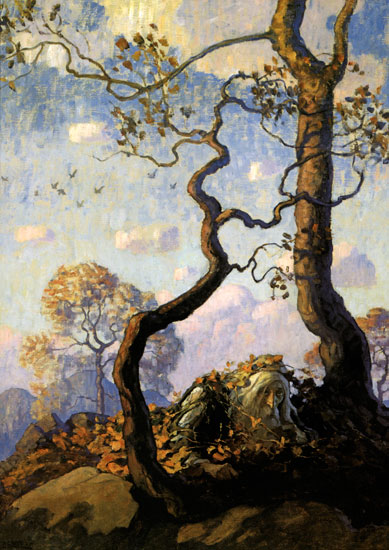

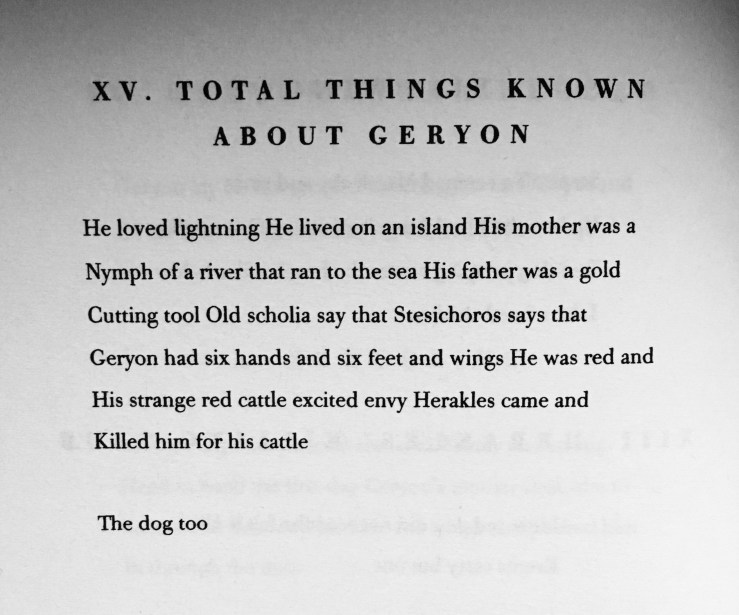

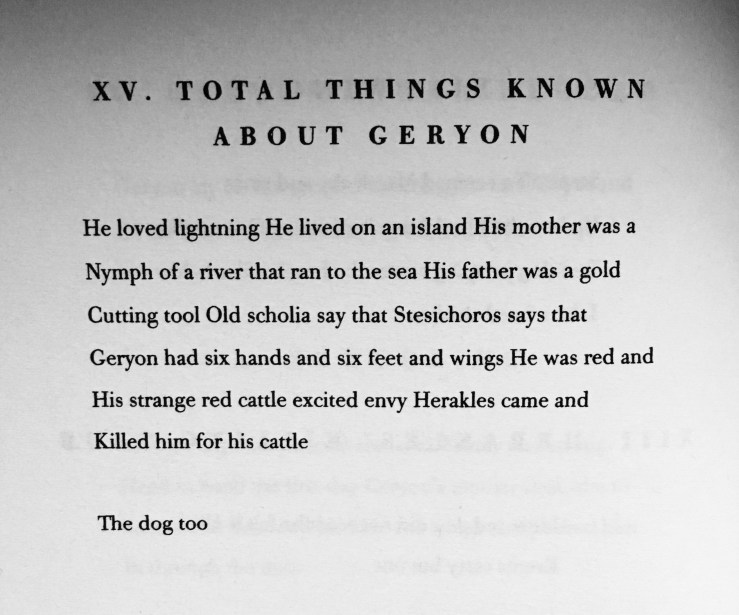

There were the two red books by Anne Carson: Autobiography of Red and Red Doc>. BLCKDGRD sent them to me back in September and I wolfed them down. Autobiography is the superior volume (which is saying something because Red Doc> is grand stuff too). What is it? What is Autobiography of Red? A novel? A poem? A history? An essay? Shall I get bogged down in description? No? Instead, let me be clear:

What I want to think/feel when I read is, How is this possible? How is this allowed?

–which is what I thought/felt reading Autobiography of Red.

From Autobiography of Red:

What else, what else?

Okay, so after the Carson I did manage a review Kazuo Ishiguro’s fantasy novel The Buried Giant—why did a review come out so much easier than anything on Carson, or, say, The Free-Lance Pall Bearers by Ishmael Reed (which I read after the Ishiguro)? Ishiguro’s book was familiar territory, fairly easy to describe—the Carson novel-poems and Reed’s picaresque performance are wholly different animals than the conventional novel.

The Free-Lance Pall Bearers by Ishmael Reed is, I hate to say, dazzling. I know what a lazy term that is, but the novella is just that—it dazzles. It zips. It zings and zounds and skips and scatters, and just when you think you have a handle on its allegorical outlines, it sticks out its tongue and jeers at you. The Free-Lance Pall Bearers is a mirthful and merciless satire on the USA written in a howling vernacular and set in an outhouse. It’s abject, picaresque, volatile, hysterical (in several of the senses of that word). I will relieve myself from summarizing the plot and instead offer this image of its perfect epigraphs:

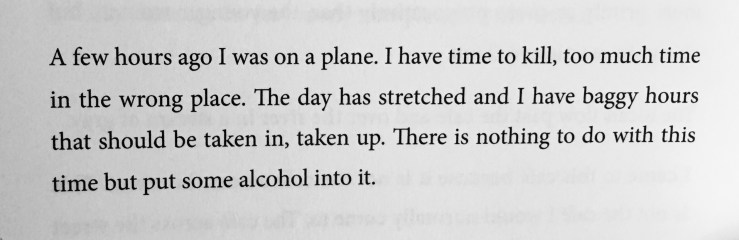

Okay and so then I read Joanna Walsh’s collection Vertigo. The stories here hum together, evoking consciousness—consciousness’s anxieties, desires, its imaginative consolations. It deserves a full proper review (or just take my word and buy it from The Dorothy Project), but in the meantime, a wonderful passage from “Half the World Over”:

I also read two more by Le Guin: Rocannon’s World (I hope to have an exchange on it with the novelist Adam Novy posted some time in the not-too-distant future), The Dispossessed, which I’ve read three times.

Also: Paul Kirchner’s The Bus 2, which, again, full review in the not-so-far-off-future. But until then, a sample: