\

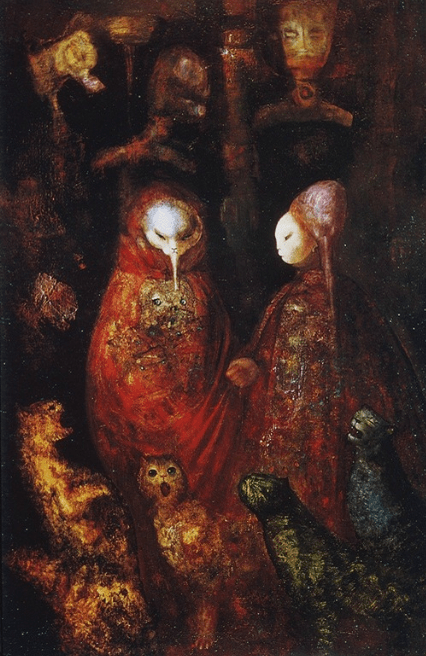

A Very Happy Picture (Un tableau très heureux), 1945 by Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012)

\

A Very Happy Picture (Un tableau très heureux), 1945 by Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012)

I’ve enjoyed dipping into the first few stories in NYRB’s collection of David R. Bunch’s Moderan stories over the past few days. Bunch’s weird world has meshed nicely with the Strugatsky’s The Snail on the Slope, which I finished today. More to come on Moderan, but here’s NRYB’s blurb for now:

Welcome to Moderan, world of the future. Here perpetual war is waged by furious masters fighting from Strongholds well stocked with “arsenals of fear” and everyone is enamored with hate. The devastated earth is coated by vast sheets of gray plastic, while humans vie to replace more and more of their own “soft parts” with steel. What need is there for nature when trees and flowers can be pushed up through holes in the plastic? Who requires human companionship when new-metal mistresses are waiting? But even a Stronghold master can doubt the catechism of Moderan. Wanderers, poets, and his own children pay visits, proving that another world is possible.

“As if Whitman and Nietzsche had collaborated,” wrote Brian Aldiss of David R. Bunch’s work. Originally published in science-fiction magazines in the 1960s and ’70s, these mordant stories, though passionately sought by collectors, have been unavailable in a single volume for close to half a century. Like Anthony Burgess in A Clockwork Orange, Bunch coined a mind-bending new vocabulary. He sought not to divert readers from the horror of modernity but to make us face it squarely.

This volume includes eleven previously uncollected Moderan stories.

Arcimboldo, 1945 by Enrico Donati (1909-2008)

Birds by Odd Nerdrum (b. 1944)

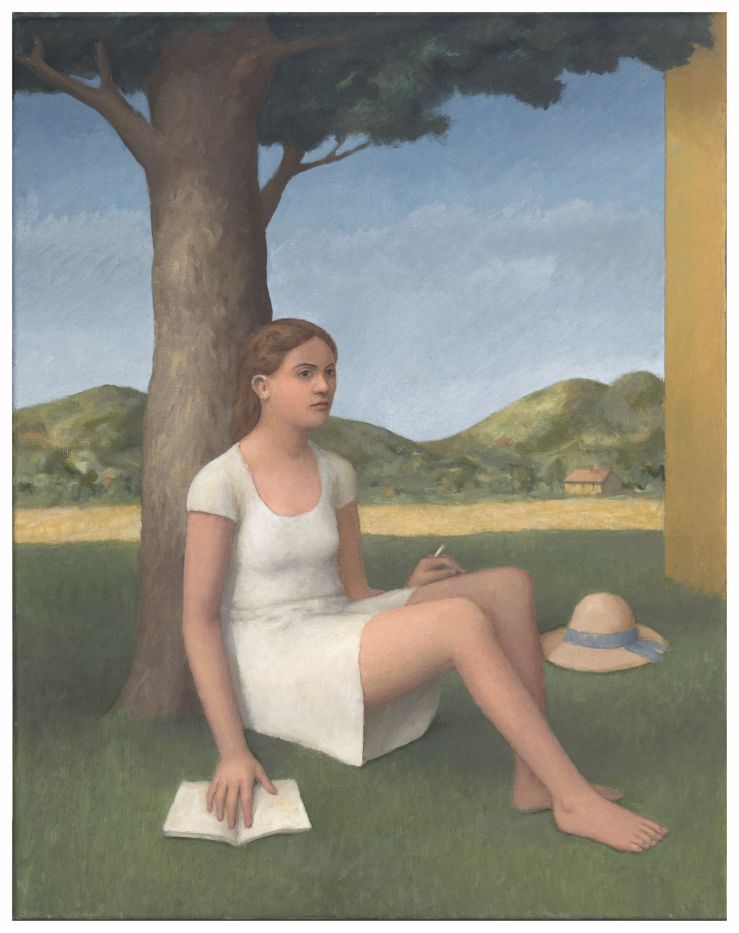

Dreaming in Umbria, 2015 by William Bailey (b. 1930)

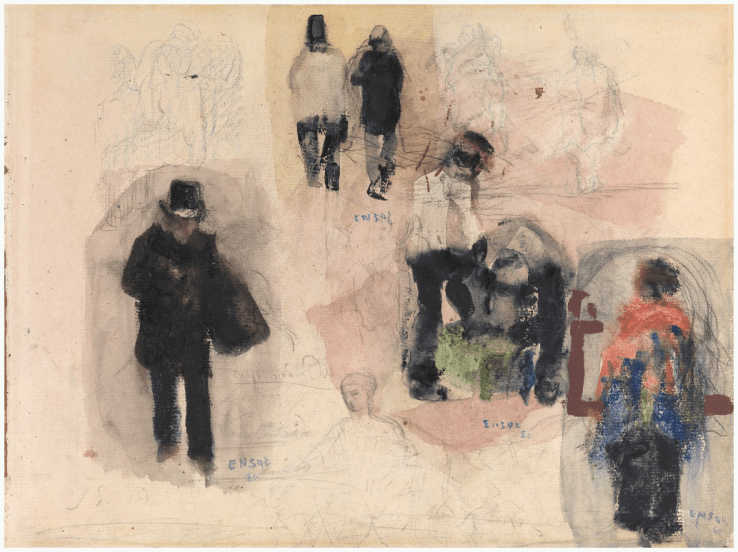

Silhouettes, 1880 by James Ensor (1860-1949)

Approaching Storm, 1940 by George Grosz (1893-1959)

Hurricane by Alphonse Legros (1837-1911)

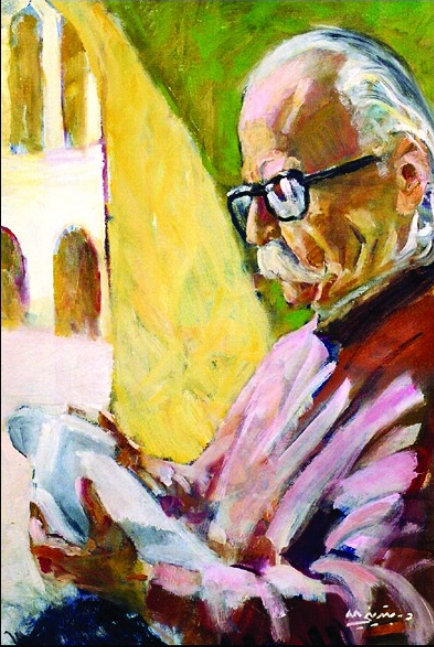

The Reader, 1988 by Wahib Bteddini (1929-2001)

At the moment, I was heading anywhere at all for breakfast, but when I heard the desk clerk’s radio playing news that an aircraft, I assumed a sightseeing plane, had struck Tower Two of the World Trade Center, I decided to jump on the number 3 subway half a block west, and go have a look.

As I headed toward Eighth Avenue I tried calling Mark Ahearn about lunch, but my cellphone only hammered out a rapid-fire beep. Please don’t ask me how this can be true: I traveled through the busy lobby and walked for half a long block on a crowded Manhattan street and then boarded the World Trade Center subway completely unaware that I was participating in a citywide disaster, and moving toward its center.

The World Trade Center station came a few stops south of Twenty-Third Street, but we didn’t get there. After Christopher Street the train halted in the tunnel and waited, humming. It gave a screech, lurched backward slightly, and stopped again. Somehow the general news had infiltrated the sealed subterranean environment that something historically enormous was happening very nearby, and it got quiet in our compartment, and almost everybody entered into a small, desperate battle with a worthless cellphone. The train moved forward and gained speed, but began braking long before Houston Street, the next station, where it halted with several rear cars sticking out behind into the tunnel. For a tense minute, whoever spoke only whispered. Then came a shout—“Tell us what’s going on!” and others raised the same cry until we heard the conductor’s PA saying something about the tracks, the tracks…“Due to the catastrophe, this train will not go farther. Please exit out the forward cars onto the platform. Do not go onto the tracks.” We were all on our feet, maneuvering selfishly, angling for the doors. But the doors didn’t open. The engine stopped. “Open the doors! Open the doors!” The engine started. A man shouted, “Just everybody stand still!” People from the car behind had pried their way into ours, and somebody almost went down. A woman said, “Stop that, you fool!” A man in front of me pushed a teenage boy beside him. With the meat of his fist he began beating the back of the boy’s head. And I jumped into the fray, didn’t you, Harrington, like a monkey, yes you did, and got yourself an elbow in the eye. The doors to the compartment flew open and people clambered out onto the station’s platform, where a dreadlocked man in a crimson athletic suit jumped up and down on a bench as if it were a trampoline, screaming “God, see what we’re doing to each other down here.” When I came up into the street, dizzy and one-eyed, I couldn’t get my bearings. I saw only one tower standing to the south, and that one ringed with fire. I asked a man nearby—“Where are we? I can’t see the other tower.” He said, “It fell” and I said, “No it didn’t.” He didn’t argue. We stood in the middle of the street with thousands of other people, all of us motionless, like a frozen parade, all silent. I began to believe the man. We watched the flames spreading through the building’s upper stories over the course of about twenty minutes, and then the eighteen-hundred-foot structure seemed to curtsy and dip left, and then it went down.

I turned around and looked at the people behind me. I saw shocked laughter, weeping, horror, bewilderment. The young man next to me bawled at the top of his lungs. I was afraid to ask him if he had a loved one in the buildings afraid to talk to him at all, but he raised his agonized, Christly face to me and suddenly laughed, saying, “Buddy, you are working on one heck of a black eye.” We stood far from the buildings—at least a mile, I’d say—far enough that we didn’t feel the ground shake, and we heard nothing but sirens, and official-sounding voices screaming, “Get out of the street! Stay out of the street!” and others too—“They’re attacking the Capitol!—the Pentagon!—the White House!”

Cop cars and ambulances heaped with dust and chunks of concrete came at us out of the south. I started walking that direction, I don’t know why, but I soon realized I was the only person heading downtown, and then the tide of panic pressing toward me was too heavy to go against, and I turned around and let it take me north.

From Denis Johnson’s short story “Doppelgänger, Poltergeist.” Collected in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, 2017.

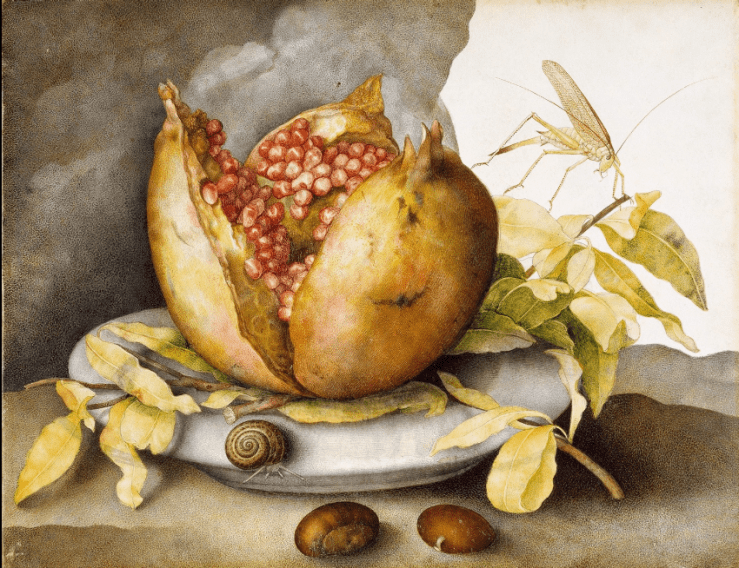

Open Pomegranate in a Dish, with Grasshopper, Snail and Two Chestnuts, c. 1652 by Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670)

September 10th.–Here is another beautiful morning, with the sun dimpling in the early sunshine. Four sail-boats are in sight, motionless on the sea, with the whiteness of their sails reflected in it. The heat-haze sleeps along the shore, though not so as quite to hide it, and there is the promise of another very warm day. As yet, however, the air is cool and refreshing. Around the island, there is the little ruffle of a breeze; but where the sail-boats are, a mile or more off, the sea is perfectly calm. The crickets sing, and I hear the chirping of birds besides.

At the base of the light-house yesterday, we saw the wings and feathers of a decayed little bird, and Mr. Thaxter said they often flew against the lantern with such force as to kill themselves, and that large quantities of them might be picked up. How came these little birds out of their nests at night? Why should they meet destruction from the radiance that proves the salvation of other beings?

Mr. Thaxter had once a man living with him who had seen “Old Bab,” the ghost. He met him between the hotel and the sea, and describes him as dressed in a sort of frock, and with a very dreadful countenance.

Two or three years ago, the crew of a wrecked vessel, a brigantine, wrecked near Boon Island, landed on Hog Island of a winter night, and found shelter in the hotel. It was from the eastward. There were six or seven men, with the mate and captain. It was midnight when they got ashore. The common sailors, as soon as they were physically comfortable, seemed to beperfectly at ease. The captain walked the floor, bemoaning himself for a silver watch which he had lost; the mate, being the only married man, talked about his Eunice. They all told their dreams of the preceding night, and saw in them prognostics of the misfortune.

There is now a breeze, the blue ruffle of which seems to reach almost across to the mainland, yet with streaks of calm; and, in one place, the glassy surface of a lake of calmness, amidst the surrounding commotion.

The wind, in the early morning, was from the west, and the aspect of the sky seemed to promise a warm and sunny day. But all at once, soon after breakfast, the wind shifted round to the eastward; and great volumes of fog, almost as dense as cannon-smoke, came sweeping from the eastern ocean, through the valley, and past the house. It soon covered the whole sea, and the whole island, beyond a verge of a few hundred yards. The chilliness was not so great as accompanies a change of wind on the mainland. We had been watching a large ship that was slowly making her way between us and the land towards Portsmouth. This was now hidden. The breeze is still very moderate; but the boat, moored near the shore, rides with a considerable motion, as if the sea were getting up.

Mr. Laighton says that the artist who adorned Trinity Church, in New York, with sculpture wanted some real wings from which to imitate the wings of cherubim. Mr. Thaxter carried him the wings of the white owl that winters here at the Shoals, together with those of some other bird; and the artist gave his cherubim the wings of an owl.

This morning there have been two boat-loads ofvisitors from Rye. They merely made a flying call, and took to their boats again,–a disagreeable and impertinent kind of people.

The Spy arrived before dinner, with several passengers. After dinner, came the Fanny, bringing, among other freight, a large basket of delicious pears to me, together with a note from Mr. B. B. Titcomb. He is certainly a man of excellent taste and admirable behavior. I sent a plateful of pears to the room of each guest now in the hotel, kept a dozen for myself, and gave the balance to Mr. Laighton.

The two Portsmouth young ladies returned in the Spy. I had grown accustomed to their presence, and rather liked them; one of them being gay and rather noisy, and the other quiet and gentle. As to new-comers, I feel rather a distaste to them; and so, I find, does Mr. Laighton,–a rather singular sentiment for a hotel-keeper to entertain towards his guests. However, he treats them very hospitably when once within his doors.

The sky is overcast, and, about the time the Spy and the Fanny sailed, there were a few drops of rain. The wind, at that time, was strong enough to raise white-caps to the eastward of the island, and there was good hope of a storm. Now, however, the wind has subsided, and the weather-seers know not what to forebode.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for September 10th, 1852. From Passages from the American Note-Books.

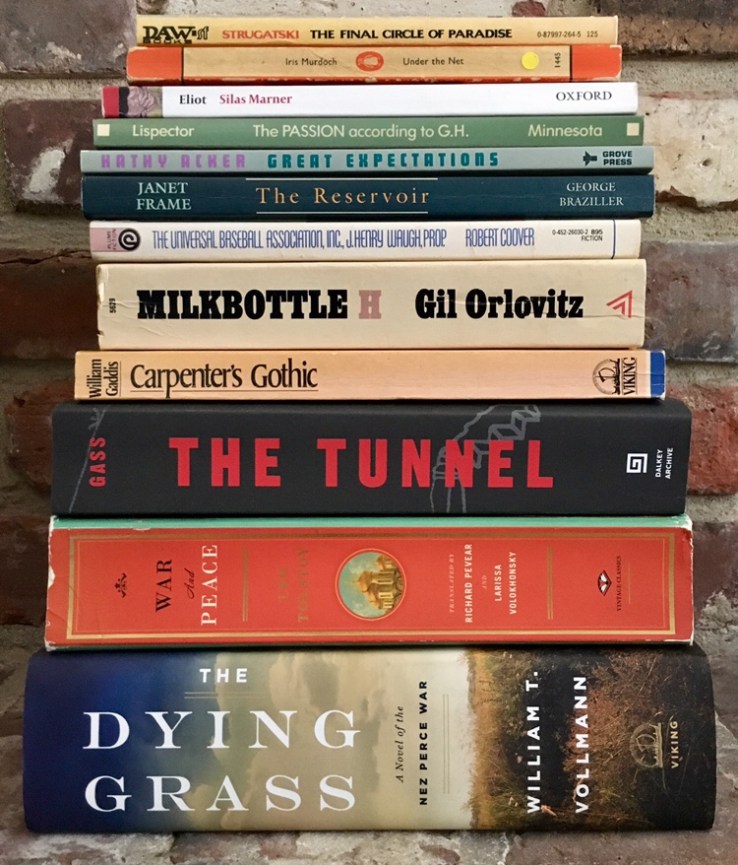

Biblioklept is twelve today.

Here are twelve books that I’ve never read before that I’ll try to read some time in the next twelve years.

From top to bottom, with no real hierarchy other than the physical heft involved in composing the photograph above—

The Final Circle of Paradise by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (trans. by Leonid Renen)

I snatched up this Daw mass market paperback of this Strugatsky brothers novel a few years ago; they aren’t as easy to find as you might think (although Chicago Review Press is slowly reissuing new translations).

Chance I’ll get to it soon: High. I’ve been on a Strugatsky kick the last two years and this is one that I physically own, so.

The Net by Iris Murdoch

I picked up a slim Penguin edition of The Net when I couldn’t find The Bell (not realizing that the “Iris Murdoch” section extended in my used bookshop and that there were plenty of copies of The Bell). I loved The Bell, and want to read more Murdoch. Folks told me not to do The Net next, but I own it. So maybe let’s call it a placeholder.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: The chance that I get to another Murdoch novel sometime later this year is very high.

Silas Marner by George Eliot

I finally read Middlemarch in 2018. I loved it but good lord it was long. Silas Marner is much shorter.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Very high. It’s on deck after I finish up a few of the shorter novels and short story collections I’m reading now.

The Passion According to G.H. by Clarice Lispector (trans. by Ronald W. Sousa)

Like seemingly every book blogger, I went through a Lispector jag in the early part of this decade, gobbling up The Hour of the Star and Near to the Wild Heart. I had thought that I’d read The Passion According to G.H., but when I pulled it out earlier this year to look for something in it, I realized I hadn’t finished it—I probably hadn’t even gotten a third of the way through, if the idle bookmark (a charming doodle by my daughter) is any indication. Furthermore, the selection I was looking for, a passage on abjection, wasn’t even in Passion—it was in Wild Heart.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Not extraordinarily high, but it’s unshelved, loose in the wilds now.

Great Expectations by Kathy Acker

I picked this one up a few weeks ago, and started in on it a bit—it’s short and has this kind of dark wild surreal icky sexy beach read vibe to it.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: I should’ve taken it camping with me next week. It’s the kind of book I want to read in a specific place that’s not, like, my couch or whatever. What I’m saying is that I’ll read this on the beach or in a tent or like, maybe you invite me down to stay at your place for a weekend but your house is so full of other guests, but, Guess what? There’s a wonderful little bedroom on your catamaran, which is docked gently right here. So after a night of good wine and good conversation, I’ll sneak off to the catamaran and read Kathy Acker before falling into wavy slumbers.

The Reservoir by Janet Frame

I read the first few of the stories in The Reservoir a few years ago and loved them but then got absorbed in something else. I was looking for a story by her to use in class, and I pulled this collection out, but it wasn’t in there. I think it’s in The New Yorker though.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Again–I pulled it out of rotation, so who knows? I’m in the midst of another short story collection (which is frankly turning into a hate read at this point), so maybe a few of these Frames will be an antidote to the Very Clever Author Whose Work I Keep Wincing At.

The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. by Robert Coover

When I picked up The Universal Baseball Association, I knew that I wasn’t going to read it anytime soon, but I also knew that I’d regret not having picked up a copy for three bucks when I had the chance. I was finishing up Going for a Beer, Coover’s recent collection of greatest hits, and was frankly exhausted with the man (the stories in A Night at the Movies can, uh, be repetitive).

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Not very high. I downloaded a copy of his novel The Origin of the Brunists one night on a lark and I don’t know if I’ll get to it any time soon either.

Milkbottle H by Gil Orlovitz

A somewhat rare cult novel with no real visible cult, Olrovitz’s Milkbottle H has been described as “the Ulysses of Philadelphia.” I found it a few weeks ago in the miscellaneous O section of my local used bookstore for three bucks. The book is long and seems to employ a mix of modernist techniques that makes it, uh, confusing at first.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Not high. Right now it’s more like a thing I want to do, but it looks like a project that will require its own special time.

Carpenter’s Gothic by William Gaddis

I hate that I still haven’t gotten past page 30 of Carpenter’s Gothic. I gave it a second shot a few years ago and then wound up rereading J R instead.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Should I prioritize this one after Silas Marner? I’m sure some new novel/review copy will get in the way, mucking things up…but should I commit to Carpenter’s Gothic? (I recently wrote about wanting to reread The Recognitions, so…).

The Tunnel by William H. Gass

I made a Serious Attempt earlier this year and stalled out.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: I will make a Serious Attempt earlier next year (and likely stall out).

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

War and Peace is one of those big books that I can’t believe I haven’t read. Earlier this year I said I’d give it a shot and then I never did (I tried The Tunnel and then settled into Middlemarch).

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Can anyone suggest a good audiobook version?

The Dying Grass by William H. Vollmann

The Dying Grass is almost 1,400 pages. I tried reading the ebook when it came out but the page breaks were weird (Vollmann has a Whitmanesque style on the page). I downloaded the audiobook which is 54 hours long, but I kept losing the thread. I picked up a used copy of the hardback for six bucks and it’s a goddamn monster.

Chance I’ll get to it soon: Try holding your breath.

Twelve Proverbs, c.1560 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder Original

Princess Maria Volkonsky at the Age of Twelve, 1945 by Balthus (1908-2001)

Ceremony, 1960 by Leonor Fini (1908-1996)