I picked up Cormac McCarthy’s new novel The Passenger today. The last Cormac McCarthy novel was The Road, which came out way back in 2006, year of this blog’s birth. I read most of The Road in the delivery ward over a few days when my daughter was born. Since then I’ve read pretty much everything by McCarthy that’s been published (excepting the screenplay for The Counselor), and a lot of it more than once. (I’ve reread Blood Meridian more times than I can think of. I fall asleep to the audiobook version sometimes when I have trouble sleeping, starting at a random chapter.) In the decade and a half after his last novel The Road became an unlikely, Oprah-endorsed hit, McCarthy wrote a screenplay for a film I can’t even pretend is any good and an article about “The Kekulé Problem,” which was published in Nautilus. He seemed to devote most of his time to hanging around the Santa Fe Institute, where he is a trustee.

Rumors of The Passenger have slipped around the internet for the past seven years—it would be about lawyer, it would be about a mathematician, it would be the first McCarthy novel to feature a woman as its main character, it would be in a wholly new style. Scraps and rumors seeped out, but like a lot of readers, I suspect, or at least readers I spoke to online and even in the flesh, I didn’t expect to see a completed version of The Passenger published in McCarthy’s lifetime. (He’s 89, just a few years younger than my dear sweet grandmother, also from Tennessee, who passed away this past Thursday.) I thought that we might see a version of the text, eventually, posthumous, possibly even cobbled together, a la Wallace’s The Pale King or Hemingway’s Garden of Eden.

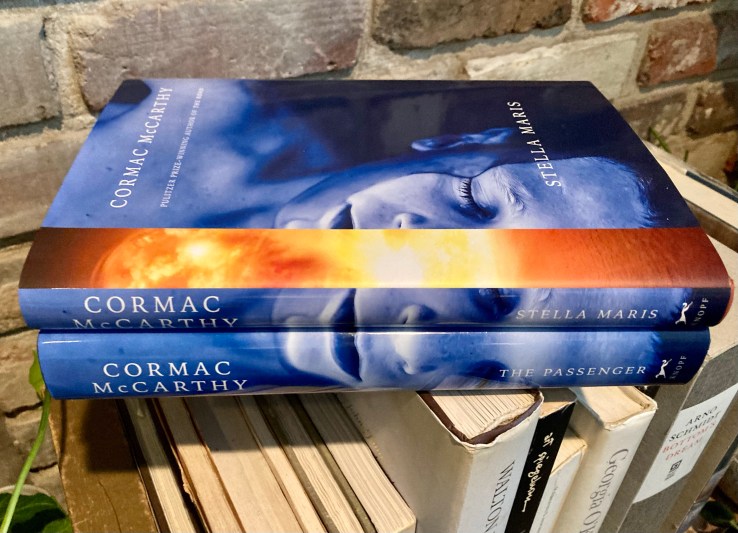

But Knopf announced not only would The Passenger publish in 2022, so too would a shorter, connected novel Stella Maris. I’ll admit I was both excited and apprehensive, especially after reading The Silence by Don DeLillo two years ago. DeLillo is (like Thomas Pynchon) just four years younger than Cormac McCarthy. And The Silence is hardly his strongest stuff. But apples and oranges: who am I to worry one old master against another old master? So I was excited. (But apprehensive.)

So I picked up Cormac McCarthy’s new novel The Passenger today. The cover is not as bad as it looked in the early internet promotional pics—not as static and flat. But it’s still not a great cover (and I say this as one partial to blue and orange, colors of my alma mater).

But a cover is not a book. I went into the pages. Before I get into the words on the pages, here’s a bit on the form of The Passenger. The novel appears to switch between two viewpoint characters: Alicia and her brother Bobby Western. (Bobby Western sounds like a William S. Burroughs character.) The Alicia passages are shorter, written completely in italics (which is fucking annoying) and given chapter numbers. The Bobby Western chapters look like regular ole Cormac McCarthy chapters.

And so well: I ended up reading the first chapter, the Alicia chapter twice. It is unlike anything else McCarthy has written. The chapter takes place in Alicia’s head in the form of a discursive discussion with “the Thalidomide Kid,” a vaudevillian interlocutor who’s quick with punning wordplay that’s rare in McCarthy’s work (of the apparent suicide note Alicia aims to write, he chides that it will be a “wintry summary”). With all his japes and clowning and weird zany energy (and hell, that name), the Thalidomide Kid seems like something more out of a Pynchon or Robert Coover story than a McCarthy novel. The closest thing that I can compare it to, at least in McCarthy’s oeuvre, is the trip scene in Suttree. I really really dig it. It’s dark and weird.

The first Alicia section ends with a dream of her brother, whom we then meet in the next section. Bobby Western is a salvage diver working with the Coast Guard in the Gulf of Mexico. It’s three am and freezing cold and there’s a jet with nine dead bodies down in the dark water. The writing here is what I would expect from McCarthy: lots of ands and thens, a general disregard for punctuation, and a lot of descriptions of men doing things. (There’s even a He spat in there!) This particular section was excerpted in The New York Times a fortnight ago, and you can read it without anything being spoiled for you, but I don’t think it’s nearly as interesting without the hallucinatory Alicia chapter that precedes it.

And that’s all I’ve got for now. I saw some lit folks I respect who have apparently read the novel already suggest that it’s Not Good, but I’ve liked what I’ve seen so far, and Want More.