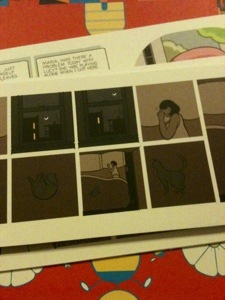

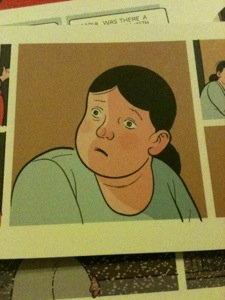

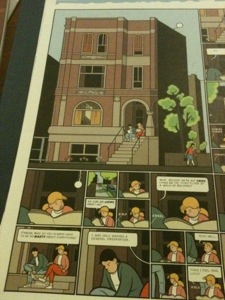

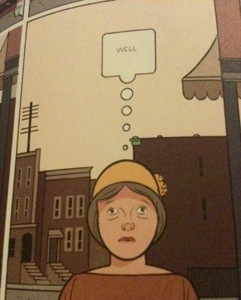

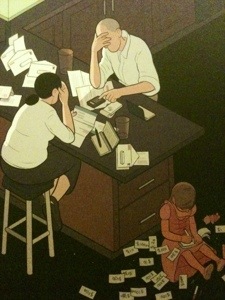

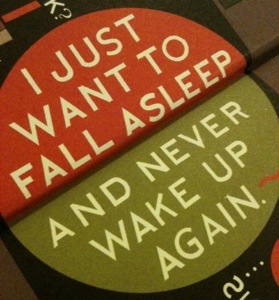

In X’ed Out, Charles Burns created a rich and strangely layered world focusing on Doug, a confused and injured young man. In his parents’ suburban basement, Doug parcels out the last of his late father’s painkillers, slipping from haunted memories of his relationship with Sarah into fevered nightmares of abject horror and then into a wholly other world, a realm that recalls William Burroughs’s Interzone. In this alien world, Doug takes on the features of Nitnit (an inversion of Tintin), the alter-ego he adopts when performing spoken word cut-ups as the opening act for local punk rock bands. What made X’ed Out so compelling (apart from Burns’s thick, precise illustration, of course), was the sense that this Interzone was a reality equal to Doug’s own “real world” — that it was somehow more real than Doug’s dreams.

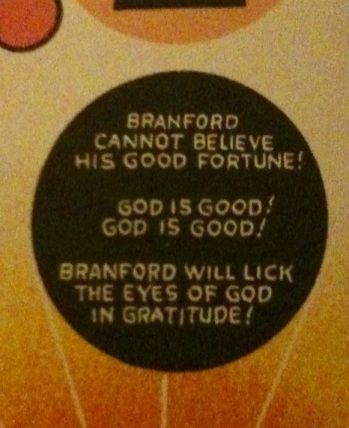

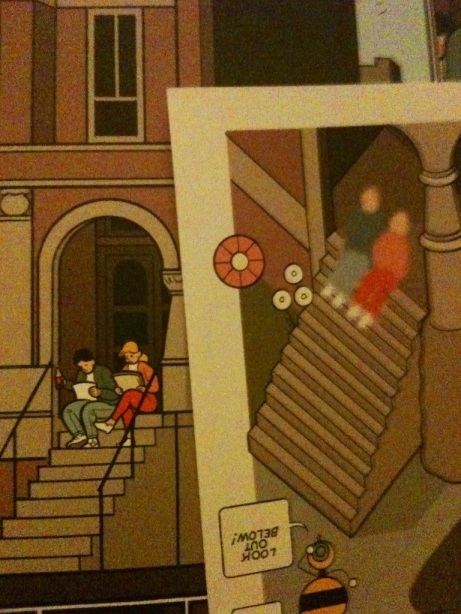

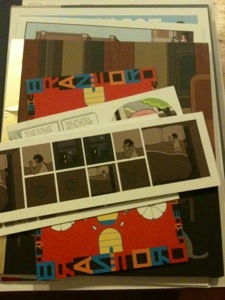

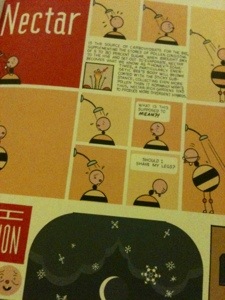

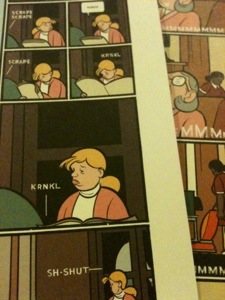

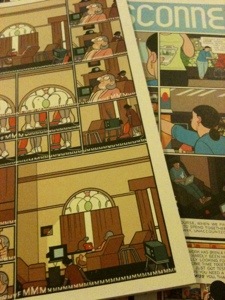

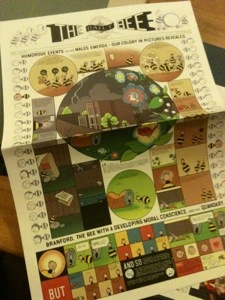

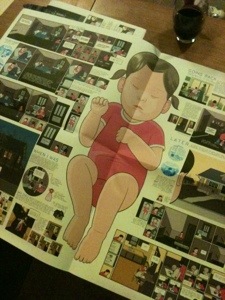

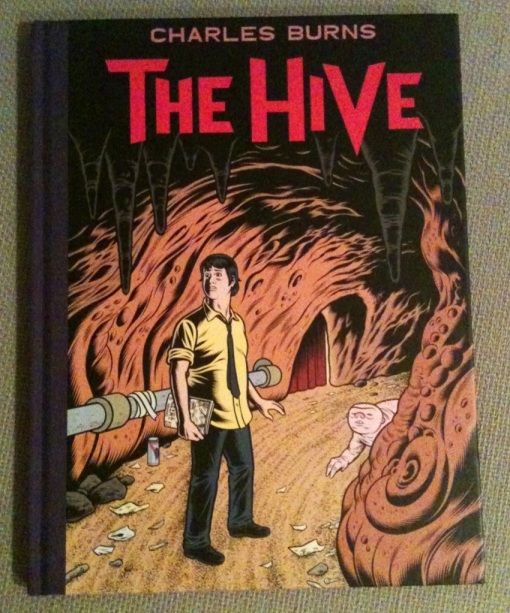

The Hive (part two of the proposed trilogy) deepens the richness and complexity of the world Burns has imagined. The title refers to a location in Interzone. Doug (or Nitnit) has found employment in The Hive as a kind of mail clerk or janitor. His primary role though is secret librarian, catering to the reading needs of the breeders of The Hive. One breeder seems to be a version of Doug’s ex-girlfriend; the other is a double of Sarah, who asks Doug/Nitnit to bring her romance comics—which he does—only he skips a few issues. These missing issues stand in for the information Doug (and Burns) withholds from the reader, the missing fragments that have been x’ed out.

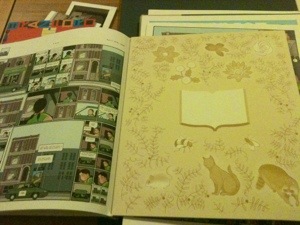

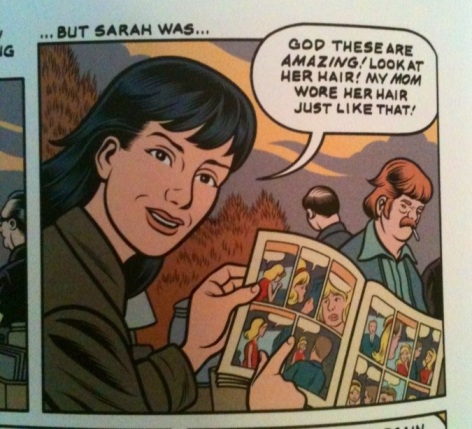

Burns uses romance comics as a framing or organizing device, a motif linking the disparate worlds of his narrative. In the “real world” — which is to say the world of Doug’s memory — we learn that he buys a stack of old romance comics for Sarah on their first date.

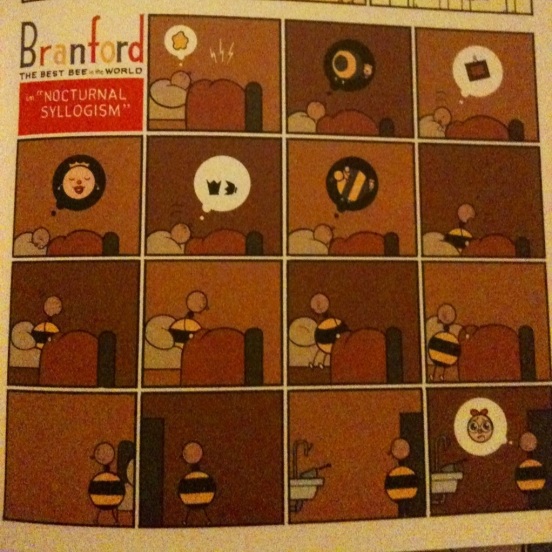

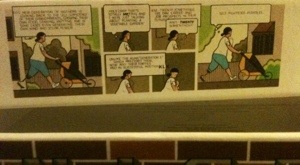

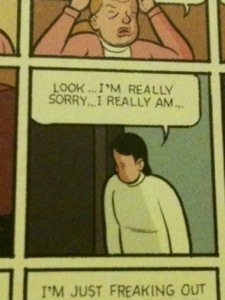

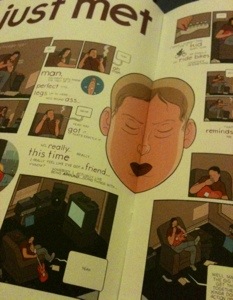

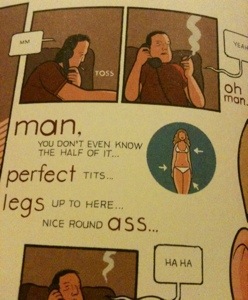

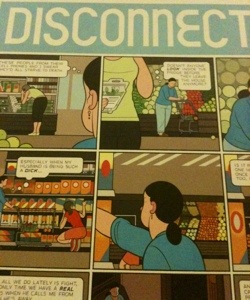

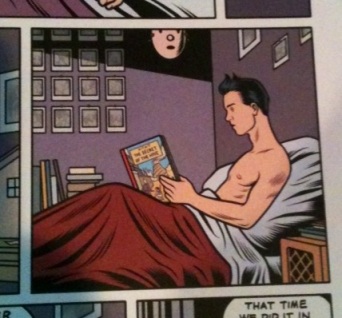

Throughout the narrative, Burns plays his characters against the extreme, often hysterical dramas of 1950s and ’60s romance comics; his strong lines and heavy inks readily recall the early works of Simon and Kirby, but more precise and careful—something closer to Roy Lichtenstein, only more sincere, more emotional.

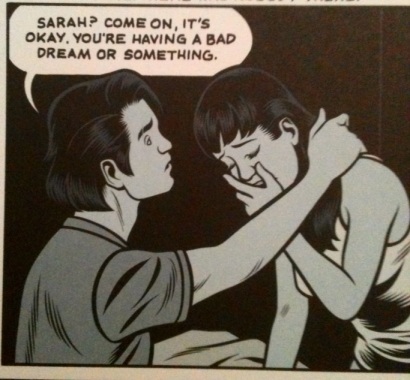

In The Hive, we learn more about Doug’s troubled relationship with Sarah, who has problems out the proverbial yingyang (not the least of which is a violent psychopathic ex-boyfriend).

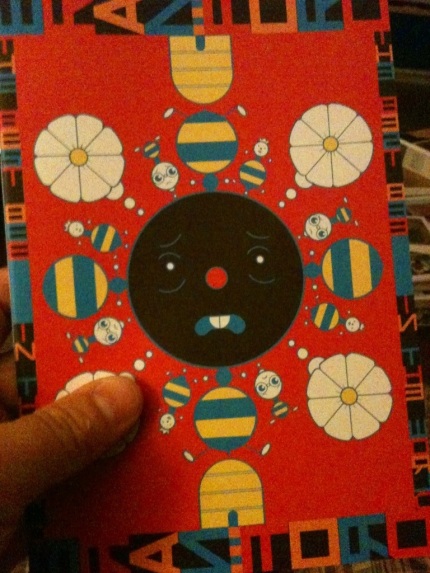

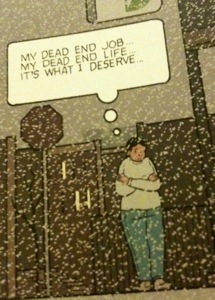

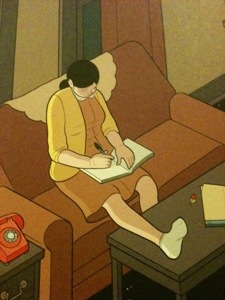

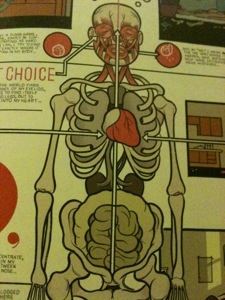

Burns weaves the story of Sarah and Doug’s relationship into the fallout of Doug’s father’s death—a death Doug was completely shuttered to, we realize. Doug’s drug-dreams dramatize the missing pieces of these narratives, and the Interzone set-pieces propel the mystery aspects of the narrative forward, as Doug’s alter-ego plumbs the detritus of his psychic fallout. Through the metatextual motif of reading-comic-books-as-detective-works, Burns explores themes of trauma, abjection, and distance. Images of pigs and cats, freaks and punks, portals and holes litter The Hive.

Burns has always been a perfectionist of dark lines and strange visions, and his last full graphic novel Black Hole was a triumph of atmosphere and mood. With the first two entries of his trilogy, however, Burns has showed a significant maturation in storytelling, characterization, and dialogue. I often thought parts of Black Hole seemed forced or rushed (no doubt because Burns faced daunting production troubles during the decade he worked on the novel—including his original publisher Kitchen Sink folding). With X’ed Out and now The Hive we can see a more patient artist, working out an emotionally complex and compelling story in rich, symbolic layers.

I reread X’ed Out and then read The Hive in one greedy sitting; then I went through The Hive again, more slowly, more attendant to its details and nuances. We had to wait two years between X’ed Out and The Hive—and it was worth the two year wait. So if we must wait another two years—or more—for the final entry, Sugar Skull, so be it.