Loretta met Anna and Sam the day she saved Sam’s life.

Anna and Sam were old. She was 80 and he was 89. Loretta would see Anna from time to time when she went to swim at her neighbor Elaine’s pool. One day she stopped by as the two women were convincing the old guy to take a swim. He finally got in, was dog-paddling along with a big grin on his face when he had a seizure. The other two women were in the shallow end and didn’t notice. Loretta jumped in, shoes and all, pulled him to the steps and up out of the pool. He didn’t need resuscitation but he was disoriented and frightened. He had some medicine to take, for epilepsy, and they helped him dry off and dress. They all sat around for a while until they were sure he was fine and could walk to their house, just down the block. Anna and Sam kept thanking Loretta for saving his life, and insisted that she go to lunch at their house the next day.

It happened that she wasn’t working for the next few days. She had taken three days off without pay because she had a lot of things that needed doing. Lunch with them would mean going all the way back to Berkeley from the city, and not finishing everything in one day, as she had planned.

Category: Literature

“It was Christmas night and the proper things had been done” (The Once and Future King)

It was Christmas night and the proper things had been done. The whole village had come to dinner in hall. There had been boar’s head and venison and pork and beef and mutton and caponsbut no turkey, because this bird had not yet been invented. There had been plum pudding and snap-dragon, with blue fire on the tips of one’s fingers, and as much mead as anybody could drink. Sir Ector’s health had been drunk with “Best respects, Measter,” or “Best compliments of the Season, my lords and ladies, and many of them.” There had been mummers to play an exciting dramatic presentation of a story in which St. George and a Saracen and a funny Doctor did surprising things, also carol-singers who rendered “Adeste Fideles” and “I Sing of a Maiden,” in high, clear, tenor voices. After that, those children who had not been sick from their dinner played Hoodman Blind and other appropriate games, while the young men and maidens danced morris dances in the middle, the tables having been cleared away. The old folks sat round the walls holding glasses of mead in their hands and feeling thankful that they were past such capers, hoppings and skippings, while those children who had not been sick sat with them, and soon went to sleep, the small heads leaning against their shoulders. At the high table Sir Ector sat with his knightly guests, who had come for the morrow’s hunting, smiling and nodding and drinking burgundy or sherries sack or malmsey wine.

After a bit, silence was prayed for Sir Grummore. He stood up and sang his old school song, amid great applausebut forgot most of it and had to make a humming noise in his moustache. Then King Pellinore was nudged to his feet and sang bashfully:

“Oh, I was born a Pellinore in famous Lincolnshire. Full well I chased the Questing Beast for more than seventeen year. Till I took up with Sir Grummore here In the season of the year. (Since when) ’tis my delight On a feather-bed night To sleep at home, my dear.

“You see,” explained King Pellinore blushing, as he sat down with everybody whacking him on the back, “old Grummore invited me home, what, after we had been having a pleasant joust together, and since then I’ve been letting my beastly Beast go and hang itself on the wall, what?”

“Well done,” they told him. “You live your own life while you’ve got it.”

William Twyti was called for, who had arrived on the previous evening, and the famous huntsman stood up with a perfectly straight face, and his crooked eye fixed upon Sir Ector, to sing:

“D’ye ken William Twyti

With his Jerkin so dagged? D’ye ken William Twyti

Who never yet lagged? Yes, I ken William Twyti,

And he ought to be gagged With his hounds and his horn in the morning.”

“Bravo!” cried Sir Ector. “Did you hear that, eh? Said he ought to be gagged, my dear feller. Blest if I didn’t think he was going to boast when he began. Splendid chaps, these huntsmen, eh? Pass Master Twyti the malmsey, with my compliments.”

The boys lay curled up under the benches near the fire, Wart with Cavall in his arms. Cavall did not like the heat and the shouting and the smell of mead, and wanted to go away, but Wart held him tightly because he needed something to hug, and Cavall had to stay with him perforce, panting over a long pink tongue.

“Now Ralph Passelewe.”

“Good wold Ralph.”

“Who killed the cow, Ralph?”

“Pray silence for Master Passelewe that couldn’t help it.”

At this the most lovely old man got up at the furthest and humblest end of the hail, as he had got up on all similar occasions for the past half-century. He was no less than eighty-five years of age, almost blind, almost deaf, but still able and willing and happy to quaver out the same song which he had sung for the pleasure of the Forest Sauvage since before Sir Ector was bound up in a kind of tight linen puttee in his cradle. They could not hear him at the high tablehe was too far away in Time to be able to reach across the roombut everybody knew what the cracked voice was singing and everybody loved it. This is what he sang:

“Whe-an/Wold King-Cole/was a /wakkin doon-t’street, H-e /saw a-lovely laid-y a /steppin-in-a-puddle. / She-a /lifted hup-er-skeat/ For to / Hop acrorst ter middle, / An ee /saw her /an-kel. Wasn’t that a fuddle? / Ee could’ernt elp it, /ee Ad to.”

There were about twenty verses of this song, in which Wold King Cole helplessly saw more and more things that he ought not to have seen, and everybody cheered at the end of each verse until, at the conclusion, old Ralph was overwhelmed with congratulations and sat down smiling dimly to a replenished mug of mead.

It was now Sir Ector’s turn to wind up the proceedings. He stood up importantly and delivered the following speech:

“Friends, tenants and otherwise. Unaccustomed as I am to public speakin’”

There was a faint cheer at this, for everybody recognized the speech which Sir Ector had made for the last twenty years, and welcomed it like a brother.

“Unaccustomed as I am to public speakin'” it is my pleasant dutyI might say my very pleasant dutyto welcome all and sundry to this our homely feast. It has been a good year, and I say it without fear of contradiction, in pasture and plow. We all know how Crumbocke of Forest Sauvage won the first prize at Cardoyle Cattle Show for the second time, and one more year will win the cup outright. More power to the Forest Sauvage. As we sit down tonight, I notice some faces now gone from among us and some which have added to the family circle. Such matters are in the hands of an almighty Providence, to which we all feel thankful. We ourselves have been first created and then spared to enjoy the rejoicin’s of this pleasant evening. I think we are all grateful for the blessin’s which have been showered upon us. Tonight we welcome in our midst the famous King Pellinore, whose labours in riddin’ our forest of the redoubtable Questin’ Beast are known to all. God bless King Pellinore. (Hear, hear!) Also Sir Grummore Grummursum, a sportsman, though I say it to his face, who will stick to his mount as long as his Quest will stand up in front of him. (Hooray!) Finally, last but not least, we are honoured by a visit from His Majesty’s most famous huntsman, Master William Twyti, who will, I feel sure, show us such sport tomorrow that we will rub our eyes and wish that a royal pack of hounds could always be huntin’ in the Forest which we all love so well. (Viewhalloo and several recheats blown in imitation.) Thank you, my dear friends, for your spontaneous welcome to these gentlemen. They will, I know, accept it in the true and warmhearted spirit in which it is offered. And now it is time that I should bring my brief remarks to a close. Another year has almost sped and it is time that we should be lookin’ forward to the challengin’ future. What about the Cattle Show next year? Friends, I can only wish you a very Merry Christmas, and, after Father Sidebottom has said our Grace for us, we shall conclude with a singin’ of the National Anthem.”

The cheers which broke out at the end of Sir Ector’s speech were only just prevented, by several hush-es, from drowning the last part of the vicar’s Grace in Latin, and then everybody stood up loyally in the firelight and sang:

“God save King Pendragon,

May his reign long drag on,

God save the King.

Send him most gorious,

Great and uproarious,

Horrible and Hoarious,

God save our King.”

The last notes died away, the hall emptied of its rejoicing humanity. Lanterns flickered outside, in the village street, as everybody went home in bands for fear of the moonlit wolves, and The Castle of the Forest Sauvage slept peacefully and lightless, in the strange silence of the holy snow.

—From T.H. White’s The Once and Future King.

A Blood Meridian Christmas

Cormac McCarthy’s seminal anti-Western Blood Meridian isn’t exactly known for visions of peace on earth and good will to man. Still, there’s a strange scene in the book’s final third that subtly recalls (and somehow inverts) the Christmas story. The scene takes place at the end of Chapter 15. The Kid, erstwhile protagonist of Blood Meridian, has just reunited with the rampaging Glanton gang after getting lost in the desert and, in a vision-quest of sorts, has witnessed “a lone tree burning on the desert” (a scene I argued earlier this year was the novel’s moral core).

Glanton’s marauders, tired and hungry, find temporary refuge from the winter cold in the town of Santa Cruz where they are fed by Mexicans and then permitted to stay the night in a barn. McCarthy offers a date at the beginning of the chapter — December 5th — and it’s reasonable to assume, based on the narrative action, that the night the gang spends in the manger is probably Christmas Eve. Here is the scene, which picks up as the gang — “they” — are led into the manger by a boy–

The shed held a mare with a suckling colt and the boy would would have put her out but they called to him to leave her. They carried straw from a stall and pitched it down and he held the lamp for them while they spread their bedding. The barn smelled of clay and straw and manure and in the soiled yellow light of the lamp their breath rolled smoking through the cold. When they had arranged their blankets the boy lowered the lamp and stepped into the yard and pulled the door shut behind, leaving them in profound and absolute darkness.

No one moved. In that cold stable the shutting of the door may have evoked in some hearts other hostels and not of their choosing. The mare sniffed uneasily and the young colt stepped about. Then one by one they began to divest themselves of their outer clothes, the hide slickers and raw wool serapes and vests, and one by one they propagated about themselves a great crackling of sparks and each man was seen to wear a shroud of palest fire. Their arms aloft pulling at their clothes were luminous and each obscure soul was enveloped in audible shapes of light as if it had always been so. The mare at the far end of the stable snorted and shied at this luminosity in beings so endarkened and the little horse turned and hid his face in the web of his dam’s flank.

The “shroud of palest fire” made of sparks is a strange image that seems almost supernatural upon first reading. The phenomena that McCarthy is describing is simply visible static electricity, which is not uncommon in a cold, dry atmosphere–particularly if one is removing wool clothing. Still, the imagery invests the men with a kind of profound, bizarre significance that is not easily explainable. It is almost as if these savage men, naked in the dark, are forced to wear something of their soul on the outside. Tellingly, this spectacle upsets both the mare and her colt, substitutions for Mary and Christ child, which makes sense. After all, these brutes are not wise men.

If civilization has an opposite, it is war (Ursula K. Le Guin)

Tibe spoke on the radio a good deal. Estraven when in power had never done so, and it was not in the Karhidish vein: their government was not a public performance, normally; it was covert and indirect. Tibe, however, orated. Hearing his voice on the air I saw again the long-toothed smile and the face masked with a net of fine wrinkles. His speeches were long and loud: praises of Karhide, disparagements of Orgoreyn vilifications of “disloyal factions,” discussions of the “integrity of the Kingdom’s borders,” lectures in history and ethics and economics, all in a ranting, canting, emotional tone that went shrill with vituperation or adulation. He talked much about pride of country and love of the parentland, but little about shifgrethor, personal pride or prestige. Had Karhide lost so much prestige in the Sinoth Valley business that the subject could not be brought up? No; for he often talked about the Sinoth Valley. I decided that he was deliberately avoiding talk of shifgrethor because he wished to rouse emotions of a more elemental, uncontrollable kind. He wanted to stir up something which the whole shifgrethor-pattern was a refinement upon, a sublimation of. He wanted his hearers to be frightened and angry. His themes were not pride and love at all, though he used the words perpetually; as he used them they meant self-praise and hate. He talked a great deal about Truth also, for he was, he said, “cutting down beneath the veneer of civilization.”

It is a durable, ubiquitous, specious metaphor, that one about veneer (or paint, or pliofilm, or whatever) hiding the nobler reality beneath. It can conceal a dozen fallacies at once. One of the most dangerous is the implication that civilization, being artificial, is unnatural: that it is the opposite of primitiveness… Of course there is no veneer, the process is one of growth, and primitiveness and civilization are degrees of the same thing. If civilization has an opposite, it is war. Of those two things, you have either one, or the other. Not both. It seemed to me as I listened to Tibe’s dull fierce speeches that what he sought to do by fear and by persuasion was to force his people to change a choice they had made before their history began, the choice between those opposites.

From Ursula Le Guin’s 1969 novel The Left Hand of Darkness. The bold emphases are mine—mea culpa, I couldn’t help it.

A Mason & Dixon Christmastide (Thomas Pynchon)

They discharge the Hands and leave off for the Winter. At Christmastide, the Tavern down the Road from Harlands’ opens its doors, and soon ev’ryone has come inside. Candles beam ev’rywhere. The Surveyors, knowing this year they’ll soon again be heading off in different Directions into America, stand nodding at each other across a Punch-bowl as big as a Bathing-Tub. The Punch is a secret Receipt of the Landlord, including but not limited to peach brandy, locally distill’d Whiskey, and milk. A raft of long Icicles broken from the Eaves floats upon the pale contents of the great rustick Monteith. Everyone’s been exchanging gifts. Somewhere in the coming and going one of the Children is learning to play a metal whistle. Best gowns rustle along the board walls. Adults hold Babies aloft, exclaiming, “The little Sausage!” and pretending to eat them. There are popp’d Corn, green Tomato Mince Pies, pickl’d Oysters, Chestnut Soup, and Kidney Pudding. Mason gives Dixon a Hat, with a metallick Aqua Feather, which Dixon is wearing. Dixon gives Mason a Claret Jug of silver, crafted in Philadelphia. There are Conestoga Cigars for Mr. Harland and a Length of contraband Osnabrigs for Mrs. H. The Children get Sweets from a Philadelphia English-shop, both adults being drawn into prolong’d Negotiations with their Juniors, as to who shall have which of. Mrs. Harland comes over to embrace both Surveyors at once. “Thanks for simmering down this Year. I know it ain’t easy.”

“What a year, Lass,” sighs Dixon.

“Poh. Like eating a Bun,” declares Mason.”

The last paragraphs of Ch. 52 of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Mason & Dixon.

Debris Stories (Book acquired, 12.09.2015)

Kevin Hardcastle’s collection Debris Stories is new this month from Biblioasis. Their blurb:

The eleven remarkable stories in Kevin Hardcastle’s debut Debris introduce an authentic new voice. Written in a lean and muscular style and brimming with both violence and compassion, these stories unflinchingly explore the lives of those—MMA fighters, the institutionalized, small-town criminals—who exist on the fringes of society, unveiling the blood and guts and beauty of life in our flyover regions

Join us at the High-Rise

“‘The Haunted Man’ by Ch_r__s D_i_ck_n_s: A Christmas Story” — Bret Harte

“‘The Haunted Man’

by Ch_r__s D_i_ck_n_s

A Christmas Story”

by

Bret Harte

PART I

THE FIRST PHANTOM

Don’t tell me that it wasn’t a knocker. I had seen it often enough, and I ought to know. So ought the three-o’clock beer, in dirty high-lows, swinging himself over the railing, or executing a demoniacal jig upon the doorstep; so ought the butcher, although butchers as a general thing are scornful of such trifles; so ought the postman, to whom knockers of the most extravagant description were merely human weaknesses, that were to be pitied and used. And so ought for the matter of that, etc., etc., etc.

But then it was such a knocker. A wild, extravagant, and utterly incomprehensible knocker. A knocker so mysterious and suspicious that policeman X 37, first coming upon it, felt inclined to take it instantly in custody, but compromised with his professional instincts by sharply and sternly noting it with an eye that admitted of no nonsense, but confidently expected to detect its secret yet. An ugly knocker; a knocker with a hard human face, that was a type of the harder human face within. A human face that held between its teeth a brazen rod. So hereafter, in the mysterious future should be held, etc., etc. Continue reading ““‘The Haunted Man’ by Ch_r__s D_i_ck_n_s: A Christmas Story” — Bret Harte”

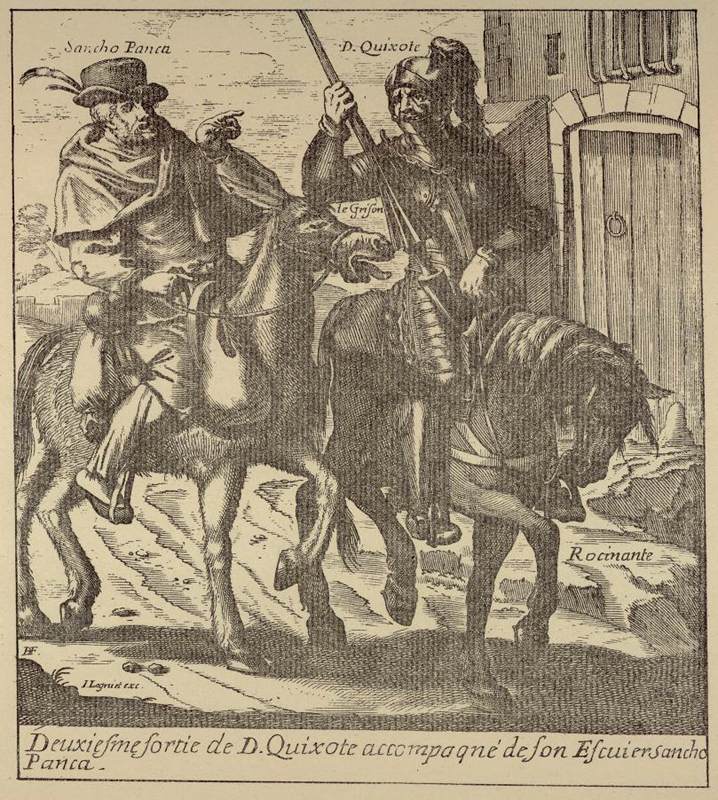

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza — Jacques Lagniet

One of the better autobiographical notes I’ve ever read

One of the better autobiographical notes I’ve read. This comes from The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Vol. E (8th ed.); my copy of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down unfortunately doesn’t actually include this note.

You have to have an interest in the world to capture the sublime. I’m not interested in the world. (Gordon Lish)

That’s the definition of racism and prejudice (Ishmael Reed)

Ishmael Reed, in a 1994 interview with Monica Valencia originally published in The Daily Californian and later republished in Conversations with Ishmael Reed.

The possibility of mislocation of the self (Donald Barthelme)

It was suggested that what was admired about the balloon was finally this: that it was not limited, or defined. Sometimes a bulge, blister, or subsection would carry all the way east to the river on its own initiative, in the manner of an army’s movements on a map, as seen in a headquarters remote from the fighting. Then that part would be, as it were, thrown back again, or would withdraw into new dispositions; the next morning, that part would have made another sortie, or disappeared altogether. This ability of the balloon to shift its shape, to change, was very pleasing, especially to people whose lives were rather rigidly patterned, persons to whom change, although desired, was not available. The balloon, for the twenty-two days of its existence, offered the possibility, in its randomness, of mislocation of the self, in contradistinctions to the grid of precise, rectangular pathways under our feet. The amount of specialized training currently needed, and the consequent desirability of long-term commitments, has been occasioned by the steadily growing importance of complex machinery, in virtually all kinds of operations; as this tendency increases, more and more people will turn, in bewildered inadequacy, to solutions for which the balloon many stand as a prototype, or “rough draft.”

The sentence is itself an odyssey | William H. Gass analyzes a sentence from Joyce’s Ulysses

Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom have stopped at a cabman’s shelter, a small coffeehouse under the Loop Line Bridge, for a cuppa and a rest on their way home. And the hope that the coffee will sober Stephen up. After an appropriate period of such hospitality, Bloom sees that it is time to leave.

James Joyce. Ulysses, (1921).

To cut a long story short Bloom, grasping the situation, was the first to rise to his feet so as not to outstay their welcome having first and foremost, being as good as his word that he would foot the bill for the occasion, taken the wise precaution to unobtrusively motion to mine host as a parting shot a scarcely perceptible sign when the others were not looking to the effect that the amount due was forthcoming, making a grand total of fourpence (the amount he deposited unobtrusively in four coppers, literally the last of the Mohicans) he having previously spotted on the printed price list for all who ran to read opposite to him in unmistakable figures, coffee ad., confectionary do, and honestly well worth twice the money once in a way, as Wetherup used to remark.

Commonplaces Narrative Events

1. to cut a long story short authorial intervention

2. grasp the situation subjective interpretation

3. rise to his feet narrative action

4. don’t outstay your welcome rationale or justification

5. first and foremost subjective evaluation

6. good as his word characterization

7. foot the bill promise, therefore a prediction

8. take the wise precaution subjective evaluation

9. mine host authorial archness

10. parting shot subjective evaluation

11. scarcely perceptible sign narrative action

12. to the effect that subjective interpretation

13. amount due is forthcoming subjective interpretation

14. grand total characterization

15. literally the last of the Mohicans authorial intervention, allusion

16. previously spotted subjective interpretation

17. all who run can read authorial intervention, allusion

18. honestly (in this context) subjective interpretation

19. well worth it subjective interpretation

20. worth twice the money subjective interpretation

21. once in a waysubjective allusion

22. as [Wetherup] used to [remark] say attribution

The sentence without its commonplaces:

To be brief, Bloom, realizing they should not stay longer, was the first to rise, and having prudently and discreetly signaled to their host that he would pay the bill, quietly left his last four pennies, a sum—most reasonable—he knew was due, having earlier seen the price of their coffee and confection clearly printed on the menu.

Bloom was the first to get up so that he might also be the first to motion (to the host) that the amount due was forthcoming.

The theme of the sentence is manners: Bloom rises so he and his companion will not have sat too long over their coffees and cake, and signals discreetly (unobtrusively is used twice) that he will pay the four pence due according to the menu. The sum, and the measure of his generosity, is a pittance.

The sentence is itself an odyssey, for Bloom and Dedalus are going home. They stop (by my count) at twenty-two commonplaces on their way. Other passages might also be considered for the list, such as “when others were not looking.” Commonplaces are the goose down of good manners. They are remarks empty of content, hence never offensive; they conceal hypocrisy in an acceptable way, because, since they have no meaning in themselves anymore they cannot be deceptive. That is, we know what they mean (“how are you?”), but they do not mean what they say (I really don’t want to know how you are). Yet they soothe and are expected. We have long forgotten that “to foot the bill,” for instance, is to pay the sum at the bottom of it, though it could mean to kick a bird in the face. Bloom, we should hope, is already well above his feet when he rises to them. The principal advantage of the commonplace is that it is supremely self-effacing. It so lacks originality that it has no source. The person who utters a commonplace—to cut a long explanation short—has shifted into neutral.

From William H. Gass’s essay “Narrative Sentences.” Collected in Life Sentences.

Read “John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving,” a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne

“John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving”

by

Nathaniel Hawthorne

On the evening of Thanksgiving day, John Inglefield, the blacksmith, sat in his elbow-chair, among those who had been keeping festival at his board. Being the central figure of the domestic circle, the fire threw its strongest light on his massive and sturdy frame, reddening his rough visage, so that it looked like the head of an iron statue, all aglow, from his own forge, and with its features rudely fashioned on his own anvil. At John Inglefield’s right hand was an empty chair. The other places round the hearth were filled by the members of the family, who all sat quietly, while, with a semblance of fantastic merriment, their shadows danced on the wall behind then. One of the group was John Inglefield’s son, who had been bred at college, and was now a student of theology at Andover. There was also a daughter of sixteen, whom nobody could look at without thinking of a rosebud almost blossomed. The only other person at the fireside was Robert Moore, formerly an apprentice of the blacksmith, but now his journeyman, and who seemed more like an own son of John Inglefield than did the pale and slender student.

Only these four had kept New England’s festival beneath that roof. The vacant chair at John Inglefield’s right hand was in memory of his wife, whom death had snatched from him since the previous Thanksgiving. With a feeling that few would have looked for in his rough nature, the bereaved husband had himself set the chair in its place next his own; and often did his eye glance thitherward, as if he deemed it possible that the cold grave might send back its tenant to the cheerful fireside, at least for that one evening. Thus did he cherish the grief that was dear to him. But there was another grief which he would fain have torn from his heart; or, since that could never be, have buried it too deep for others to behold, or for his own remembrance. Within the past year another member of his household had gone from him, but not to the grave. Yet they kept no vacant chair for her.

While John Inglefield and his family were sitting round the hearth with the shadows dancing behind them on the wall, the outer door was opened, and a light footstep came along the passage. The latch of the inner door was lifted by some familiar hand, and a young girl came in, wearing a cloak and hood, which she took off, and laid on the table beneath the looking-glass. Then, after gazing a moment at the fireside circle, she approached, and took the seat at John Inglefield’s right hand, as if it had been reserved on purpose for her. Continue reading “Read “John Inglefield’s Thanksgiving,” a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne”

Happy Thanksgiving! Here’s a bunch of literary recipes and a Bosch painting

Enjoy Thanksgiving with this menu of literary recipes:

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Turkey Twelve Ways

Zora Neale Hurston’s Mulatto Rice

James Joyce’s Burnt Kidney Breakfast

Herman Melville’s Whale Steaks

Ernest Hemingway’s Absinthe Cocktail, Death in the Afternoon

Vladimir Nabokov’s Eggs à la Nabocoque

Thomas Pynchon’s Banana Breakfast

Robert Crumb’s Macaroni Casserole

Truman Capote’s Caviar-Smothered Baked Potatoes with 80-Proof Russian Vodka

Emily Dickinson’s Cocoanut Cake

Thomas Jefferson’s Vanilla Ice Cream

Christmas Bonus: George Orwell’s Recipes for Plum Cake and Christmas Pudding

A planet spoiled by the human species (Ursula K. Le Guin)

My world, my Earth, is a ruin. A planet spoiled by the human species. We multiplied and gobbled and fought until there was nothing left, and then we died. We controlled neither appetite nor violence; we did not adapt. We destroyed ourselves. But we destroyed the world first. There are no forests left on my Earth. The air is grey, the sky is grey, it is always hot. It is habitable, it is still habitable, but not as this world is. This is a living world, a harmony. Mine is a discord. You Odonians chose a desert; we Terrans made a desert. . . . We survive there as you do. People are tough! There are nearly a half billion of us now. Once there were nine billion. You can see the old cities still everywhere. The bones and bricks go to dust, but the little pieces of plastic never do—they never adapt either. We failed as a species, as a social species. We are here now, dealing as equals with other human societies on other worlds, only because of the charity of the Hainish. They came; they brought us help. They built ships and gave them to us, so we could leave our ruined world. They treat us gently, charitably, as the strong man treats the sick one. They are a very strange people, the Hainish; older than any of us; infinitely generous. They are altruists. They are moved by a guilt we don’t even understand, despite all our crimes. They are moved in all they do, I think, by the past, their endless past. Well, we had saved what could be saved, and made a kind of life in the ruins, on Terra, in the only way it could be done: by total centralization. Total control over the use of every acre of land, every scrap of metal, every ounce of fuel. Total rationing, birth control, euthanasia, universal conscription into the labor force. The absolute regimentation of each life toward the goal of racial survival. We had achieved that much, when the Hainish came. They brought us . . . a little more hope. Not very much. We have outlived it. . . . We can only look at this splendid world, this vital society, this Urras, this Paradise, from the outside. We are capable only of admiring it, and maybe envying it a little. Not very much.

From Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed.