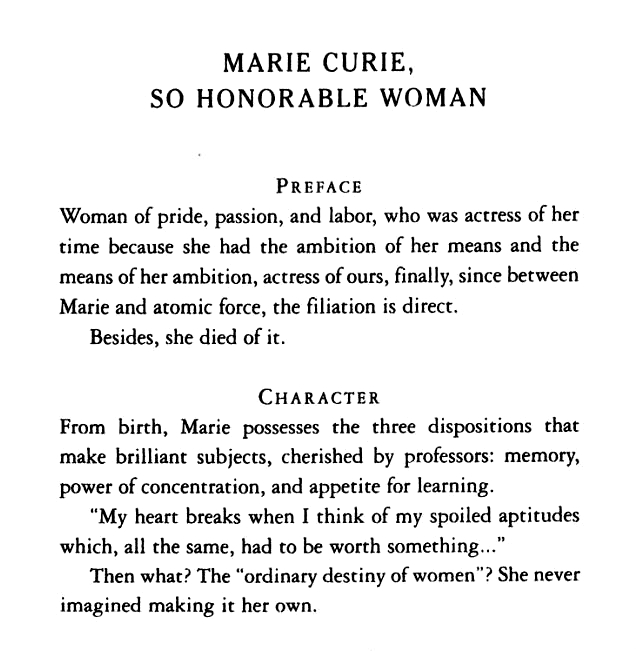

The first two sections of one of my favorite short stories, Lydia Davis’s “Marie Curie, So Honorable Woman.” Collected in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis.

The first two sections of one of my favorite short stories, Lydia Davis’s “Marie Curie, So Honorable Woman.” Collected in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis.

“The Disciple”

by

Oscar Wilde

When Narcissus died the pool of his pleasure changed from a cup of sweet waters into a cup of salt tears, and the Oreads came weeping through the woodland that they might sing to the pool and give it comfort.

And when they saw that the pool had changed from a cup of sweet waters into a cup of salt tears, they loosened the green tresses of their hair and cried to the pool and said, ‘We do not wonder that you should mourn in this manner for Narcissus, so beautiful was he.’

‘But was Narcissus beautiful?’ said the pool.

‘Who should know that better than you?’ answered the Oreads. ‘Us did he ever pass by, but you he sought for, and would lie on your banks and look down at you, and in the mirror of your waters he would mirror his own beauty.’

And the pool answered, ‘But I loved Narcissus because, as he lay on my banks and looked down at me, in the mirror of his eyes I saw ever my own beauty mirrored.’

Osvaldo Ferrari: Many people still ask whether Borges believes in God, because at times they feel he does and at times that he doesn’t.

Jorge Luis Borges: If God means something in us that strives for good, yes. If he’s thought of as an individual being, then no, I don’t believe. I believe in an ethical proposition, perhaps not in the universe but in each one of us. And if I could I would add, like Blake, an aesthetic and an intellectual proposition but with reference to individuals again. I’m not sure it would apply to the universe. I remember Tennyson’s line: “Nature red in tooth and claw.” He wrote that because so many people talked about a gentle Nature.

From Conversations Volume I, a newly-translated collections of radio discussions between Jorge Luis Borges and Osvaldo Ferrari. Read the rest of the excerpt at NYRB.

“The Young Girl”

by

Katherine Mansfield

In her blue dress, with her cheeks lightly flushed, her blue, blue eyes, and her gold curls pinned up as though for the first time—pinned up to be out of the way for her flight—Mrs. Raddick’s daughter might have just dropped from this radiant heaven. Mrs. Raddick’s timid, faintly astonished, but deeply admiring glance looked as if she believed it, too; but the daughter didn’t appear any too pleased—why should she?—to have alighted on the steps of the Casino. Indeed, she was bored—bored as though Heaven had been full of casinos with snuffy old saints for croupiers and crowns to play with.

“You don’t mind taking Hennie?” said Mrs. Raddick. “Sure you don’t? There’s the car, and you’ll have tea and we’ll be back here on this step—right here—in an hour. You see, I want her to go in. She’s not been before, and it’s worth seeing. I feel it wouldn’t be fair to her.”

“Oh, shut up, mother,” said she wearily. “Come along. Don’t talk so much. And your bag’s open; you’ll be losing all your money again.”

“I’m sorry, darling,” said Mrs. Raddick.

“Oh, do come in! I want to make money,” said the impatient voice. “It’s all jolly well for you—but I’m broke!”

“Here—take fifty francs, darling, take a hundred!” I saw Mrs. Raddick pressing notes into her hand as they passed through the swing doors. Continue reading ““The Young Girl” — Katherine Mansfield”

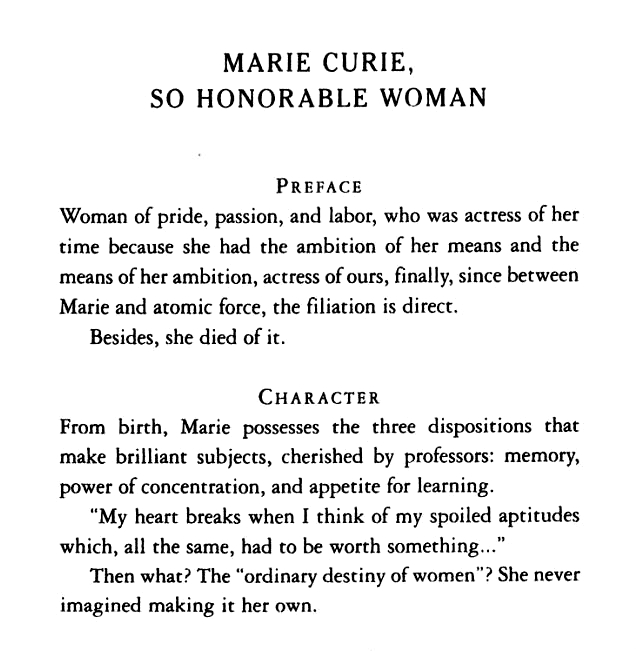

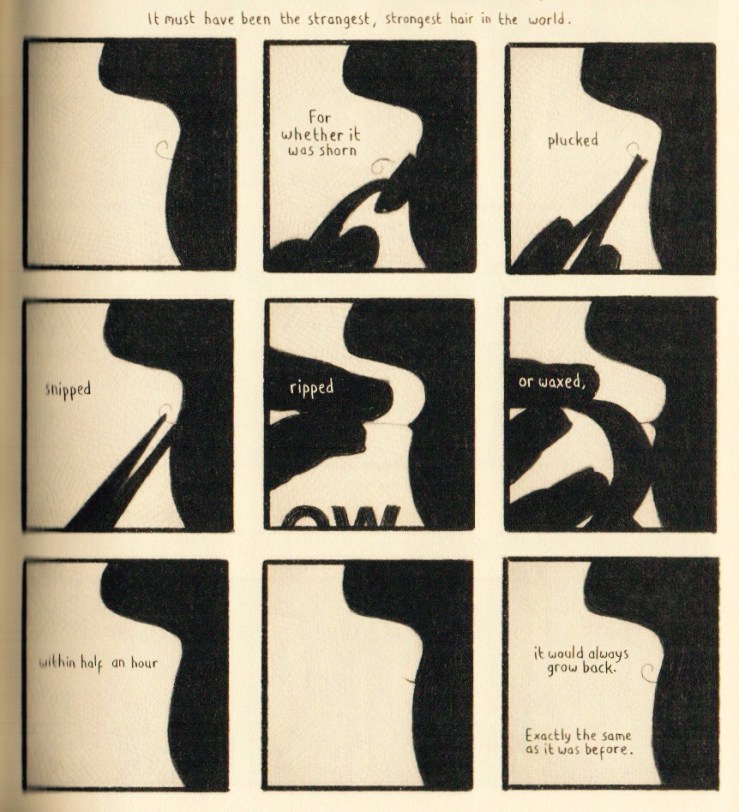

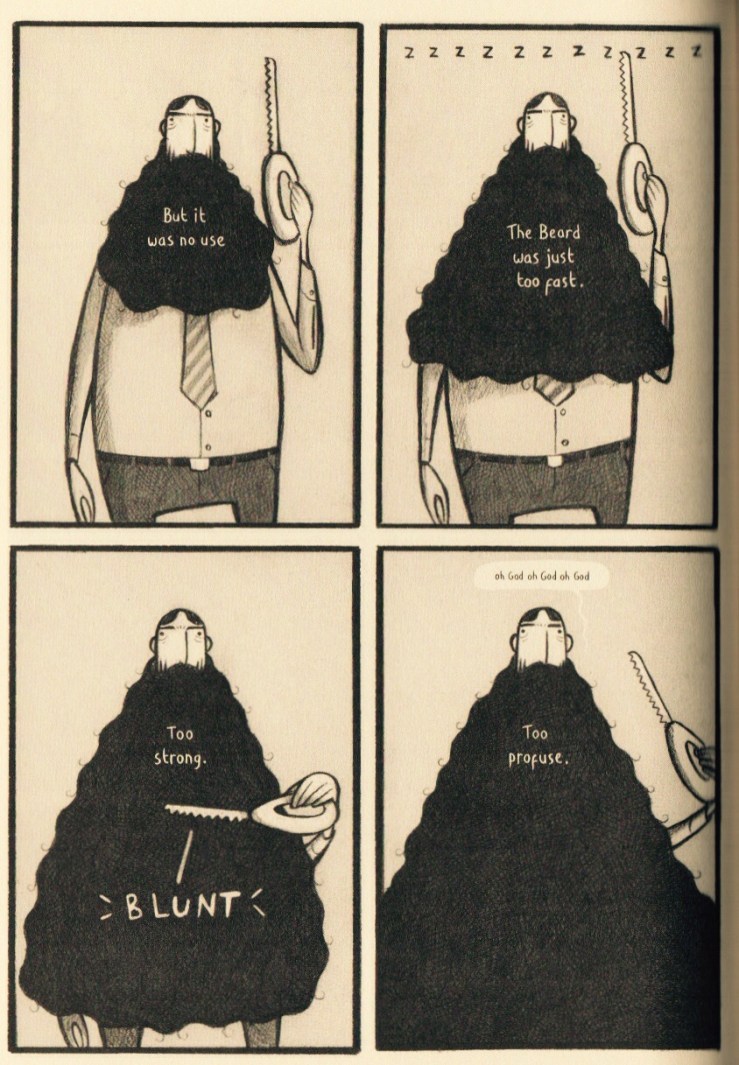

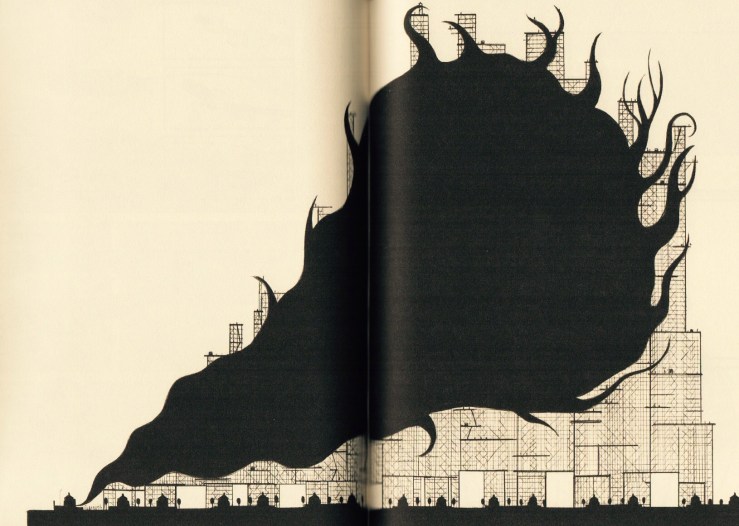

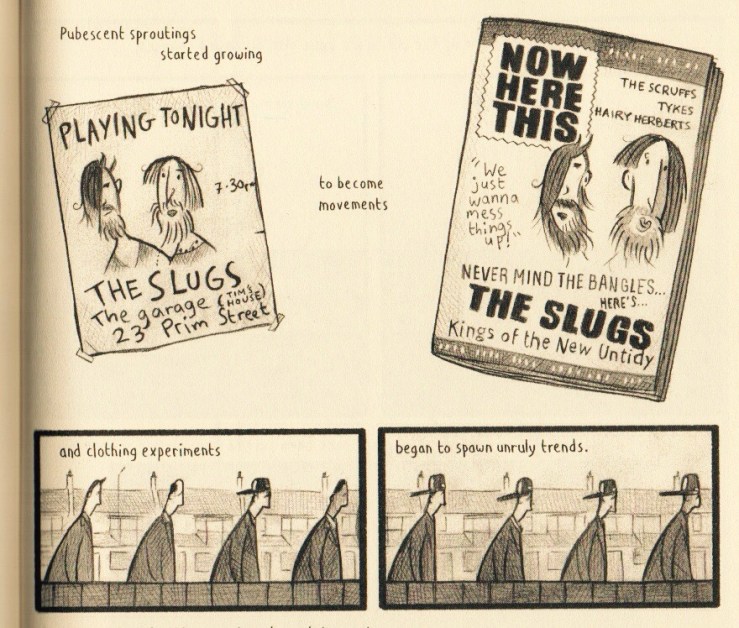

Stephen Collins’s début graphic novel The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil tells the story of Dave, an especially average (forgive the oxymoron) guy in the neat-and-tidy island of Here, a place where conformity rules and difference is unthinkable. Dave fits like a cog into his tidy world until a beard erupts from his face, severing him from society.

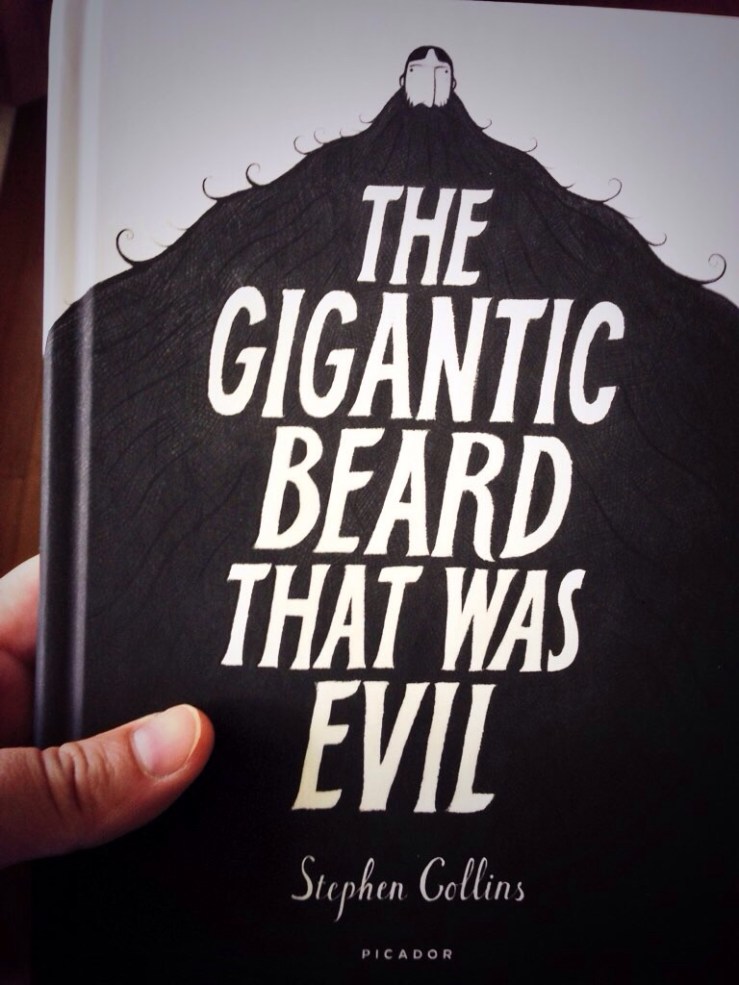

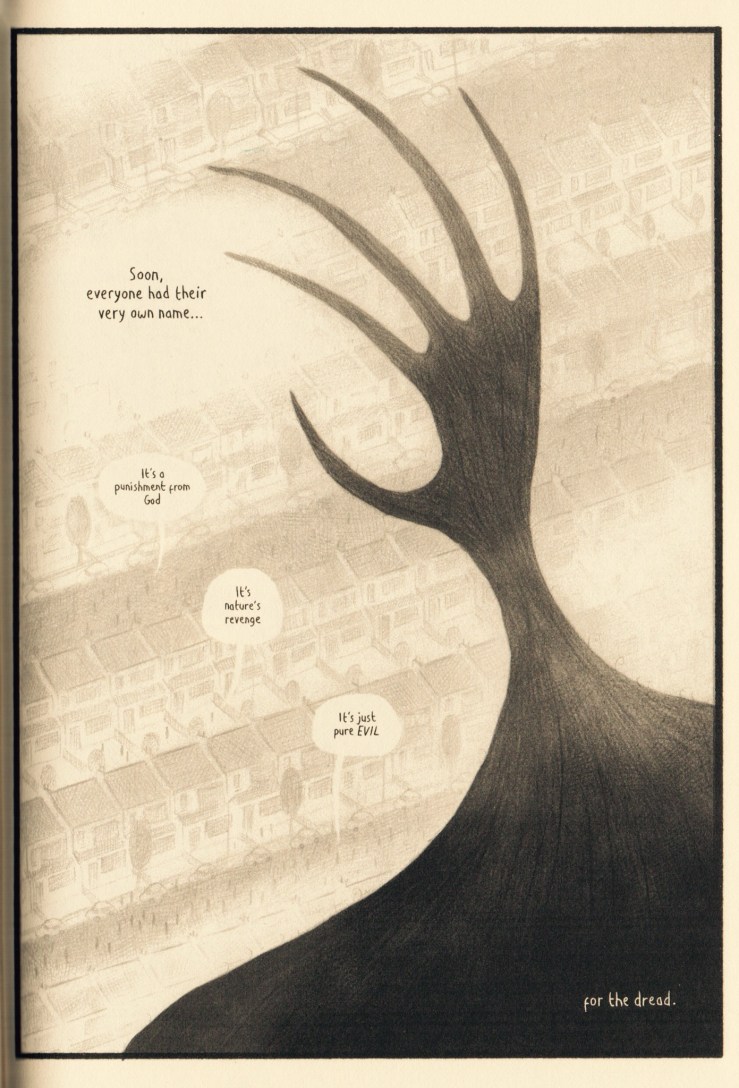

Despite its neat and tidy contours, an omnipresent dread of otherness gestates in the egg-shaped isle of Here. That dread manifests in the fabled land of There. Dave’s psyche is haunted by There; its very existence threatens both body and mind. Collins renders this anxiety in a remarkable series of panels that concretize Dave’s nightmare of otherness:

Dave’s nightmare highlights his subconscious realization that there cannot be a Here without a There. The realization leaves him abject, torn, and destabilized, even before his beard appears. When the first hairs do arrive, Dave’s interior existential crisis spills outward, his messy difference oozing out to disrupt and upset the tidy normalcy of Here.

Poor Dave.

The beard quickly becomes a national emergency requiring enormous resources. Police, military, the media, and eventually the entire society become entangled in the crisis. United against a common foe, the citizens of Here are nevertheless distracted, letting their grooming habits slip. Things become less tidy. In their battle against the beard, they overlook the greater war on weird.

The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil is an allegorical fable. Collins attacks conformity and fear of otherness, but also depicts just how complex and horrifying otherness can be. While the island of Here is clearly a stand-in for England, Collins’s satire of xenophobia and the dangers of groupthink will resonate pretty much everywhere. All kinds of 21st-century anxieties writhe under the text: fear of immigration, the collapse of cultural homogeneity, ecological devastation—the end of a particular way of life. The angry mob castigating poor Dave call him a terrorist, but they are the authors of their own terror.

In an unexpected and rewarding fourth act, Collins examines the aftermath of what comes to be known as “The Beard Event.” The Untidiness that happened while the citizens of Here were distracted dealing with Dave becomes the new normal. Fits of nonconformity inevitably become trends, then commodities.

The Beard Event eventually becomes “A story many times retold and resold,” complete with its own museum (enter through the gift shop). Collins offers a clear depiction of difference—how it’s first feared, then resisted and attacked, and eventually absorbed and recycled.

I’ve tried to offer enough of Collin’s words and art to convey a sense of his simple but refined style. His lines are often gentle and always precise, his subtle shading all the color this tale needs. The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil succeeds visually on the strength of Collins’s pacing and panel design. Collins seamlessly integrates his prose into the panels, moving the story along in a lilt of rhymes and non-rhymes evocative of Edward Gorey or Roald Dahl. Collins nimbly avoids the potential pitfalls of preachiness or meaningless absurdity here, leading to a confident and convincing début. I look forward to more. Great stuff.

The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil is now available in the United States in hardback and ebook from Picador.

30 October. In the afternoon to the theatre, Pallenberg.

The possibilities within me, I won’t say to act or write The Miser, but to be the miser himself. It would need only a sudden determined movement of my hands, the entire orchestra gazes in fascination at the spot above the conductor’s stand where the baton will rise.

Feeling of complete helplessness.

What is it that binds you more intimately to these impenetrable, talking, eye-blinking bodies than to any other thing, the penholder in your hand, for example? Because you belong to the same species? But you don’t belong to the same species, that’s the very reason why you raised this question.

The impenetrable outline of human bodies is horrible.

The wonder, the riddle of my not having perished already, of the silent power guiding me. It forces one to this absurdity: ‘Left to my own resources, I should have long ago been lost.’ My own resources.

From Franz Kafka’s diary entry of October 30, 1921.

“The Middle Toe of the Right Foot”

by

Ambrose Bierce

It is well known that the old Manton house is haunted. In all the rural district near about, and even in the town of Marshall, a mile away, not one person of unbiased mind entertains a doubt of it; incredulity is confined to those opinionated persons who will be called “cranks” as soon as the useful word shall have penetrated the intellectual demesne of the Marshall Advance. The evidence that the house is haunted is of two kinds; the testimony of disinterested witnesses who have had ocular proof, and that of the house itself. The former may be disregarded and ruled out on any of the various grounds of objection which may be urged against it by the ingenious; but facts within the observation of all are material and controlling.

In the first place the Manton house has been unoccupied by mortals for more than ten years, and with its outbuildings is slowly falling into decay—a circumstance which in itself the judicious will hardly venture to ignore. It stands a little way off the loneliest reach of the Marshall and Harriston road, in an opening which was once a farm and is still disfigured with strips of rotting fence and half covered with brambles overrunning a stony and sterile soil long unacquainted with the plow. The house itself is in tolerably good condition, though badly weather-stained and in dire need of attention from the glazier, the smaller male population of the region having attested in the manner of its kind its disapproval of dwelling without dwellers. It is two stories in height, nearly square, its front pierced by a single doorway flanked on each side by a window boarded up to the very top. Corresponding windows above, not protected, serve to admit light and rain to the rooms of the upper floor. Grass and weeds grow pretty rankly all about, and a few shade trees, somewhat the worse for wind, and leaning all in one direction, seem to be making a concerted effort to run away. In short, as the Marshall town humorist explained in the columns of the Advance, “the proposition that the Manton house is badly haunted is the only logical conclusion from the premises.” The fact that in this dwelling Mr. Manton thought it expedient one night some ten years ago to rise and cut the throats of his wife and two small children, removing at once to another part of the country, has no doubt done its share in directing public attention to the fitness of the place for supernatural phenomena. Continue reading ““The Middle Toe of the Right Foot” — Ambrose Bierce”

“What Was It?”

by

Fitz James O’Brien

It is, I confess, with considerable diffidence, that I approach the strange narrative which I am about to relate. The events which I purpose detailing are of so extraordinary a character that I am quite prepared to meet with an unusual amount of incredulity and scorn. I accept all such beforehand. I have, I trust, the literary courage to face unbelief. I have, after mature consideration resolved to narrate, in as simple and straightforward a manner as I can compass, some facts that passed under my observation, in the month of July last, and which, in the annals of the mysteries of physical science, are wholly unparalleled.

I live at No. —— Twenty-sixth Street, in New York. The house is in some respects a curious one. It has enjoyed for the last two years the reputation of being haunted. It is a large and stately residence, surrounded by what was once a garden, but which is now only a green enclosure used for bleaching clothes. The dry basin of what has been a fountain, and a few fruit trees ragged and unpruned, indicate that this spot in past days was a pleasant, shady retreat, filled with fruits and flowers and the sweet murmur of waters.

The house is very spacious. A hall of noble size leads to a large spiral staircase winding through its center, while the various apartments are of imposing dimensions. It was built some fifteen or twenty years since by Mr. A——, the well-known New York merchant, who five years ago threw the commercial world into convulsions by a stupendous bank fraud. Mr. A——, as everyone knows, escaped to Europe, and died not long after, of a broken heart. Almost immediately after the news of his decease reached this country and was verified, the report spread in Twenty-sixth Street that No. —— was haunted. Legal measures had dispossessed the widow of its former owner, and it was inhabited merely by a caretaker and his wife, placed there by the house agent into whose hands it had passed for the purposes of renting or sale. These people declared that they were troubled with unnatural noises. Doors were opened without any visible agency. The remnants of furniture scattered through the various rooms were, during the night, piled one upon the other by unknown hands. Invisible feet passed up and down the stairs in broad daylight, accompanied by the rustle of unseen silk dresses, and the gliding of viewless hands along the massive balusters. The caretaker and his wife declared they would live there no longer. The house agent laughed, dismissed them, and put others in their place. The noises and supernatural manifestations continued. The neighborhood caught up the story, and the house remained untenanted for three years. Several persons negotiated for it; but, somehow, always before the bargain was closed they heard the unpleasant rumors and declined to treat any further. Continue reading ““What Was It?” — Fitz James O’Brien”

The narrator of David Foster Wallace’s posthumous novel The Pale King assures us at one point that “phantoms are not the same as real ghosts.”

Okay.

So what’s a phantom then, at least in the universe of The Pale King?

Phantom refers to a particular kind of hallucination that can afflict rote examiners at a certain threshold of concentrated boredom.

The “rote examiners” are IRS agents who perform Sisyphean tasks of boredom. They are also placeholders for anyone who works a boring, repetitive job.

(We might even wax a bit here on the phrase rote examiner—the paradox in it—that to examine should require looking at the examined with fresh eyes, a fresh spirit—a spirit canceled out by the modifier rote).

In The Pale King, phantoms visit the rote examiners who toil in wiggle rooms. The “phantoms are always deeply, diametrically different from the examiners they visit,” suggesting two simultaneous outcomes: 1) an injection of life-force, a disruption of stasis that serves to balance out the examiner’s personality and 2) in the novel’s own language, “the yammering mind-monkey of their own personality’s dark, self-destructive side.”

In one scene, desperate Lane Dean contemplates suicide on the job, until he’s visited by a phantom.

“Yes but now that you’re getting a taste, consider it, the word. You know the one.”

The word is boredom, and the phantom proceeds to give a lecture on its etymology:

Word appears suddenly in 1766. No known etymology. The Earl of March uses it in a letter describing a French peer of the realm. He didn’t cast a shadow, but that didn’t mean anything. For no reason, Lane Dean flexed his buttocks. In fact the first three appearances of bore in English conjoin it with the adjective French, that French bore, that boring Frenchman, yes? The French of course had malaise, ennui. See Pascal’s fourth Pensée, which Lane Dean heard as pantsy.

(Thank you, narrator—who are you?!—for mediating the phantom’s speech and Dean’s misauditing of that speech). Continue reading “Phantoms and Ghosts in DFW’s Novel The Pale King (Ghost Riff 2)”

“A Relation of the Apparition of Mrs. Veal”

by

Daniel Defoe

The Preface

This relation is matter of fact, and attended with such circumstances, as may induce any reasonable man to believe it. It was sent by a gentleman, a justice of peace, at Maidstone, in Kent, and a very intelligent person, to his friend in London, as it is here worded; which discourse is attested by a very sober and understanding gentlewoman, a kinswoman of the said gentleman’s, who lives in Canterbury, within a few doors of the house in which the within-named Mrs. Bargrave lives; who believes his kinswoman to be of so discerning a spirit, as not to be put upon by any fallacy; and who positively assured him that the whole matter, as it is related and laid down, is really true; and what she herself had in the same words, as near as may be, from Mrs. Bargrave’s own mouth, who, she knows, had no reason to invent and publish such a story, or any design to forge and tell a lie, being a woman of much honesty and virtue, and her whole life a course, as it were, of piety. The use which we ought to make of it, is to consider, that there is a life to come after this, and a just God, who will retribute to every one according to the deeds done in the body; and therefore to reflect upon our past course of life we have led in the world; that our time is short and uncertain; and that if we would escape the punishment of the ungodly, and receive the reward of the righteous, which is the laying hold of eternal life, we ought, for the time to come, to return to God by a speedy repentance, ceasing to do evil, and learning to do well: to seek after God early, if happily he may be found of us, and lead such lives for the future, as may be well pleasing in his sight.

A Relation of the Apparition of Mrs. Veal

This thing is so rare in all its circumstances, and on so good authority, that my reading and conversation has not given me anything like it: it is fit to gratify the most ingenious and serious inquirer. Mrs. Bargrave is the person to whom Mrs. Veal appeared after her death; she is my intimate friend, and I can avouch for her reputation, for these last fifteen or sixteen years, on my own knowledge; and I can confirm the good character she had from her youth, to the time of my acquaintance. Though, since this relation, she is calumniated by some people, that are friends to the brother of this Mrs. Veal, who appeared; who think the relation of this appearance to be a reflection, and endeavour what they can to blast Mrs. Bargrave’s reputation, and to laugh the story out of countenance. But by the circumstances thereof, and the cheerful disposition of Mrs. Bargrave, notwithstanding the ill-usage of a very wicked husband, there is not yet the least sign of dejection in her face; nor did I ever hear her let fall a desponding or murmuring expression; nay, not when actually under her husband’s barbarity; which I have been witness to, and several other persons of undoubted reputation.

Now you must know, Mrs. Veal was a maiden gentlewoman of about thirty years of age, and for some years last past had been troubled with fits; which were perceived coming on her, by her going off from her discourse very abruptly to some impertinence. She was maintained by an only brother, and kept his house in Dover. She was a very pious woman, and her brother a very sober man to all appearance; but now he does all he can to null or quash the story. Mrs. Veal was intimately acquainted with Mrs. Bargrave from her childhood. Mrs. Veal’s circumstances were then mean; her father did not take care of his children as he ought, so that they were exposed to hardships; and Mrs. Bargrave, in those days, had as unkind a father, though she wanted neither for food nor clothing, whilst Mrs. Veal wanted for both; insomuch that she would often say, Mrs. Bargrave, you are not only the best, but the only friend I have in the world, and no circumstance of life shall ever dissolve my friendship. They would often condole each other’s adverse fortunes, and read together Drelincourt upon Death, and other good books; and so, like two Christian friends, they comforted each other under their sorrow. Continue reading ““A Relation of the Apparition of Mrs. Veal” — Daniel Defoe”

The truth is that there are two actual, non-hallucinatory ghosts haunting Post 047’s wiggle room. No one knows whether there are any in the Immersive Pods; those Pods are worlds unto themselves.

The ghosts’ names are Garrity and Blumquist. Much of the following info comes after the fact from Claude Sylvanshine. Blumquist is a very bland, dull, efficient rote examiner who died at his desk unnoticed in 1980. Some of the older examiners actually worked with him in rotes in the 1970s. The other ghost is older. Meaning dating from an earlier historical period. Garrity had evidently been a line inspector for Mid West Mirror Works in the mid-twentieth century. His job was to examine each one of a certain model of decorative mirror that came off the final production line, for flaws. A flaw was usually a bubble or unevenness in the mirror’s aluminum backing that caused the reflected image to distend or distort in some way. Garrity had twenty seconds to check each mirror. Industrial psychology was a primitive discipline then, and there was little understanding of non-physical types of stress. In essence, Garrity sat on a stool next to a slow-moving belt and moved his upper body in a complex system of squares and butterfly shapes, examining his face’s reflection at very close range. He did this three times a minute, 1,440 times per day, 356 days a year, for eighteen years. Toward the end he evidently moved his body in the complex inspectorial system of squares and butterfly shapes even when he was off-duty and there were no mirrors around. In 1964 or 1965 he had apparently hanged himself from a steam pipe in what is now the north hallway off the REC Annex’s wiggle room. Among the staff at 047, only Claude Sylvanshine knows anything detailed about Garrity, whom he’s never actually seen—and then most of what Sylvanshine gets is repetitive data on Garrity’s weight, belt size, the topology of optical flaws, and the number of strokes it takes to shave with your eyes closed. Garrity is the easier of the wiggle room’s two ghosts to mistake for a phantom because he’s extremely chatty and distracting and thus is often taken by wigglers straining to maintain concentration as the yammering mind-monkey of their own personality’s dark, self-destructive side.

Blumquist is different. When Blumquist manifests in the air near an examiner, he just basically sits with you. Silently, without moving. Only a slight translucence about Blumquist and his chair betrays anything untoward. He’s no bother. It’s not like he stares at you in an uncomfortable way. You get the sense that he just likes to be there. The sense is ever so slightly sad. He has a high forehead and mild eyes made large by his glasses. Sometimes he’s hatted; sometimes he holds the hat by the brim as he sits. Except for those examiners who spasm out at any sort of visitation—and these are the rigid, fragile ones who are ripe for phantom-visits anyhow, so it’s something of a vicious circle—except for these, most examiners accept or even like a visit from Blumquist. He has a few he seems to favor, but he is quite democratic. The wigglers find him companionable. But no one ever speaks of him.