“Paolo Ucello, Painter”

by

Marcel Schwob

from Imaginary Lives

translated by Lorimer Hammond

His real name was Paolo di Dono, but the Florentines called him Uccelli or Paul of the Birds because of the many bird figures and painted beasts in his house, for he was too poor to feed live animals or to obtain those strange species he did not know.

At Padua he was said to have executed a fresco of the four elements, with an image of a chameleon representing the air. He had never seen one, so he made it a sort of pot bellied camel with a gaping snout (while the chameleon, explains Vasari, resembles a small dry lizard and the camel is a great humped beast). Uccello was not concerned with the reality of things but in their multiplicity and the infinity of their lines. He made fields blue, cities red, and cavaliers in black armour on ebony horses with blazing mouths, the lances of the riders radiating toward every quarter of the heavens. He had a fancy for drawing the mazocchio, a headdress made of wooden hoops so covered that th

e cloth fell down in pleats all about the wearer’s face. Uccello drew pointed ones and square ones and others in pyramids and cones, following every intricacy of their perspectives so studiously as to find a world of combinations in their folds. The sculptor Donatello used to say to him: “Ah, Paolo, you leave the substance for the shadow.”

The Bird continued his patient work, assembling circles, dividing angles, examining all creatures under all their aspects. From his friend Giovanni Manetti, the mathematician, he learned of the problems of Euclid, then shut himself up to cover panels and parchments with points and curves. Aided by Filippo Brunelleschi, he perpetually employed himself at the study of architecture, but he had no intention to build. He wanted only to know the directions of lines from foundation to cornice, the convergences of parallels together with their intersections, the manner in which vaulting turns upon its keys and the perspective of ceiling beams as they appear to unite at the ends of long rooms. He drew all beasts, all their movements and all the gestures of men, reducing these things to simple lines.

Then like an alchemist who mixes ores and metals in his furnace, watching their fusion in hope of finding the secret of gold, Uccello would throw all his forms into a crucible, mix them, mingle them and melt them, striving to transmute them into one ideal form containing all. That was why Paolo Uccello lived like an alchemist at the back of his little house. He believed he might find the knowledge to merge all lines into a single aspect; he wanted to see the universe as it should be reflected in the eye of God, all figures springing from one complex centre. Near him lived Ghiberti, della Robbia, Brunelleschi and Donatello, each one proud and a master of his art. They railed at poor Uccello for his folly of perspectives, with his house full of cobwebs empty of provisions. But Uccello was prouder than they. At each new combination of lines he imagined he had discovered the way. It was not imitation he sought, but the sovereign power to create all things, and his strange drawings of pleated hats were to him more revealing than magnificent marble figures by the great Donatello.

That was how The Bird lived: like a hermit, with his musing head wrapped in his cape, noting neither what he ate nor what he drank.

One day along a meadow, near a ring of old stones deep in the grass, he saw a laughing girl with a garland on her head. She wore a thin dress held to her hips by a pale ribbon and her movements were supple as the reeds she gathered. Her name was Selvaggia. She smiled at Uccello. Noting the flexion of her smile when she looked at him, he saw the little lines of her lashes, the patterned circles of the iris, the curve of her lids and all the minute interlacements of her hair. Considering the garland across her forehead, he described it to himself in a multitude of geometric postures, but Selvaggia knew nothing of all that, for she was only thirteen.

She took Uccello by the hand and he loved her. She was the daughter of a Florentine dyer, her mother was dead and another woman had come to her father’s house and had beaten her. Uccello took her home with him. Selvaggia used to kneel all day by the wall whereon Uccello traced his universal forms.

She never understood why he preferred to regard those straight and arched lines instead of the tender face she raised to him. At night, when Manetti or Brunelleschi came to work with Uccello, she would sleep at the foot of the scaffolding, in the circle of shadow beyond the lamplight. In the morning she arose before him, rejoicing because she was surrounded by painted birds and coloured beasts.

Uccello drew her lips, her eyes, her hair, her hands; he recorded all the attitudes of her body but he never made her portrait as did other painters when they loved a woman. For The Bird had no pleasure imitating individuals. He never dwelt in the one place – he tried to soar over all places in his flight.

So Selvaggia’s forms were tossed into his crucible along with the movements of beasts, the lines of plants and stones, rays of light, billowings of clouds above the earth and the rippling of sea waves.

Without thought for the girl, he lived in eternal meditation upon his crucible of forms.

There came a time when nothing remained to eat in Uccello’s house. Selvaggia did not speak of this to Donatello or the others; she kept her silence and died. Uccello drew the stiffening lines of her body, the union of her thin little hands, her closed eyes. He no more realized she was dead than he had ever realized she was alive. But he threw these new forms among all the others he had gathered.

The Bird grew old. His pictures were no longer understood by men, who recognized in them neither earth nor plant nor animal, seeing only a confusion of curves. For many years he had been working on his supreme masterpiece which he hid from all eyes. It was to embrace all his research and all the images he had ever conceived. The subject was Saint Thomas, incredulous, tempting the wrath of Christ. Uccello completed this work when he was eighty. Calling Donatello to his house he uncovered it piously before him and Donatello said: “Oh, Paolo, cover your picture!” Though The Bird questioned him, the great sculptor would say no more, then Uccello knew he had accomplished a miracle. But Donatello had seen only a mass of lines.

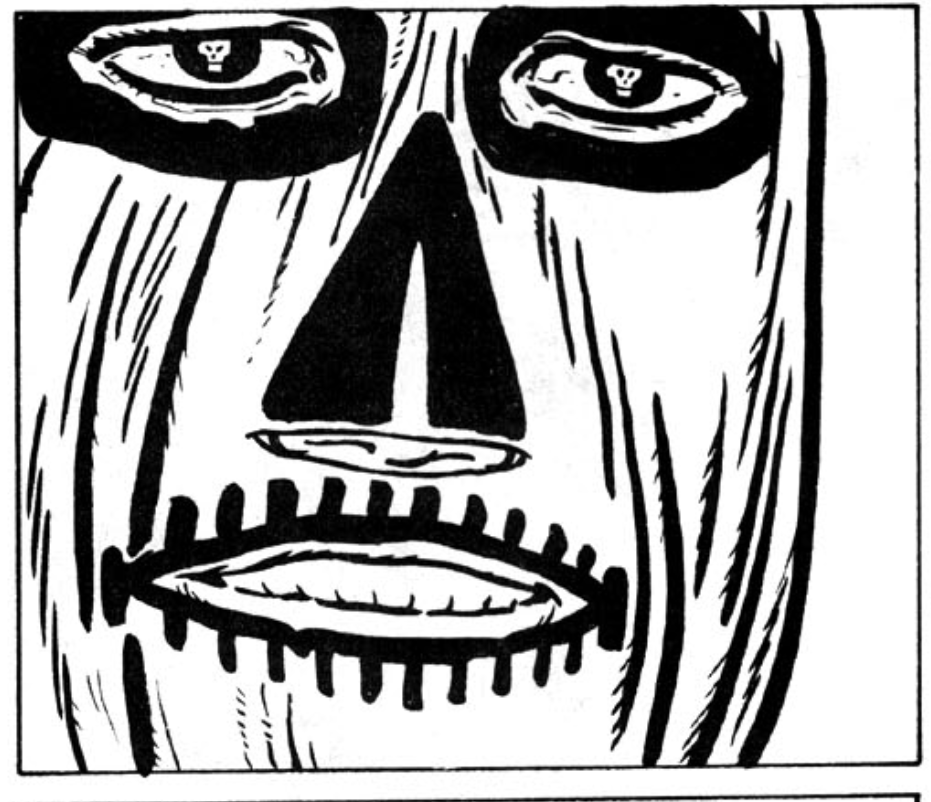

A few years later they found Paolo Uccello dead in his bed, worn out with age. His face was covered with wrinkles, his eyes fixed on some mysterious revelation. Tight in his rigid hand he clutched a little parchment disc on which a network of lines ran from the centre to the circumference and returned from the circumference to the centre.