“Presents”

by

Donald Barthelme

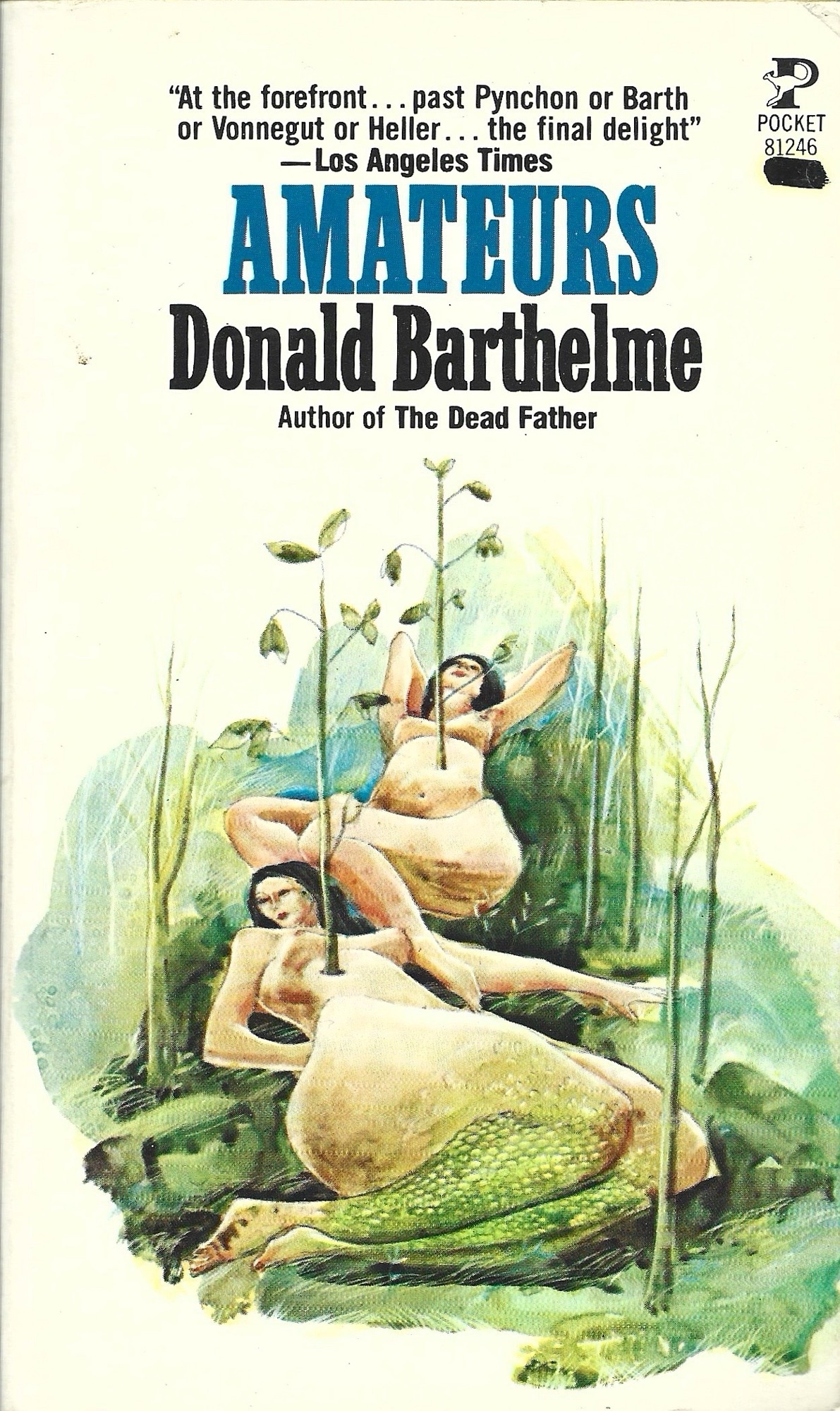

In the middle of a forest. Parked there is a handsome 1932 Ford, its left rear door open. Two young women are pausing, about to step into the car. Each has one foot on the running board. Both are naked. They have their arms around each other’s waist in sisterly embrace. The woman on the left is dark, the one on the right fair. Their white, graceful backs are in sharp contrast to the shiny black of the Ford. The woman on the right has turned her head to hear something her companion is saying.

At a dinner party. The eight guests are seated, in shining white plastic shells mounted on steel pedestals, in a luxurious kitchen. They sit around a long table of polished rosewood, at one end of which there is a wicker basket filled with fruit, pineapples, bananas, pears, and at the other a wicker basket containing loaves of burnt-orange bread. The kitchen floor is polished black tile; electric ovens with bronze fronts are set into the polished off-white walls. On thick glass shelves above the diners, handsome pots with herbs, jams, jellies, and tall glass jars with half-a-dozen varieties of raw pasta. Six of the guests, men and women, are conventionally clothed. The two young women (one dark, one fair) are naked, smoking cigarillos. One of them unfolds a large white linen napkin and smoothes it over her companion’s lap.

Ten o’clock in the morning. Marble, more marble, together with walnut paneling, a terrazzo floor, on the left a long (sixty feet) black-topped counter behind which the tellers sit, on the right a beige-carpeted area with three rows (three times three) of bank officers, suited and gowned. At the back, the great vault door open, functionary seated at desk reading a Gothic novel. In the center, long lines of depositors channeled to the tellers by a flattened S-curve of blue velvet ropes. Uniformed guards, etc., the American flag drooping on its standard near the vault. Two young women enter. They are naked except for black masks. One is dark, one fair. They place themselves back-to-back in the center of the banking floor. The guards rush toward them, then rush away again.

A woman seated on a plain wooden chair under a canopy. She is wearing white overalls and has a pleased expression on her face. Watching her, two dogs, German shepherds, at rest. Behind the dogs, with their backs to us, a row of naked women kneeling, sitting on their heels, their buttocks perfect as eggs or O’s — OOOOOOOOOOOOO. In profile to the scene, at the far right, Henry James — his calm, accepting gaze.

Two young women wrapped as gifts. But the gift-wrapping is indistinguishable from ordinary clothing. Or there is a distinction, in that what they are wearing is perhaps a shade newer, brighter, more studied than ordinary clothing, proclaims the specialness of what is wrapped, argues for immediate unwrapping, or if not that, unwrapping at leisure, with wine, cheese, sour cream.

Two young women, naked, tied together by a long red thread. One is dark, one is fair.

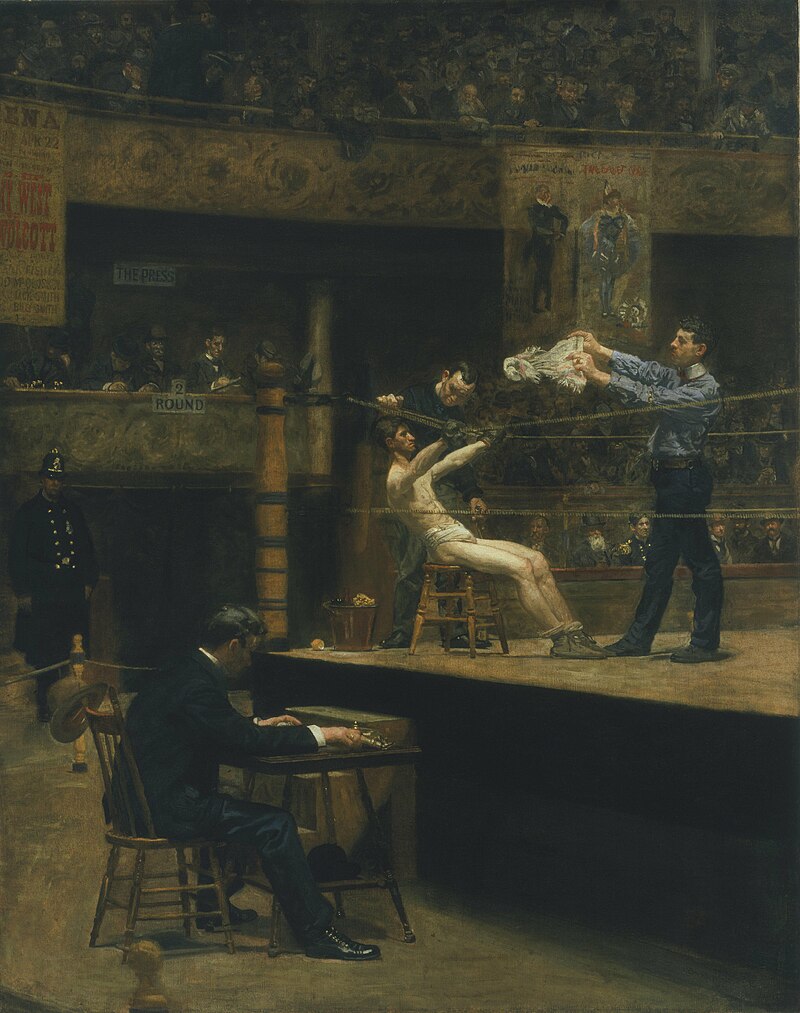

Large (eight by ten feet) sheets of white paper on the floor, six or eight of them. The total area covered is perhaps 200 feet square; some of the sheets overlap. A string quartet is playing at one edge of this area, and irregular rows of handsomely-dressed spectators border another. A large bucket of blue paint sits on the paper. Two young women, naked. Each has her hair rolled up in a bun; each has been splashed, breasts, belly, and thighs, with blue paint. One, on her belly, is being dragged across the paper by the other, who is standing, gripping the first woman’s wrists. Their backs are not painted. Or not painted with. The artist is Yves Klein.

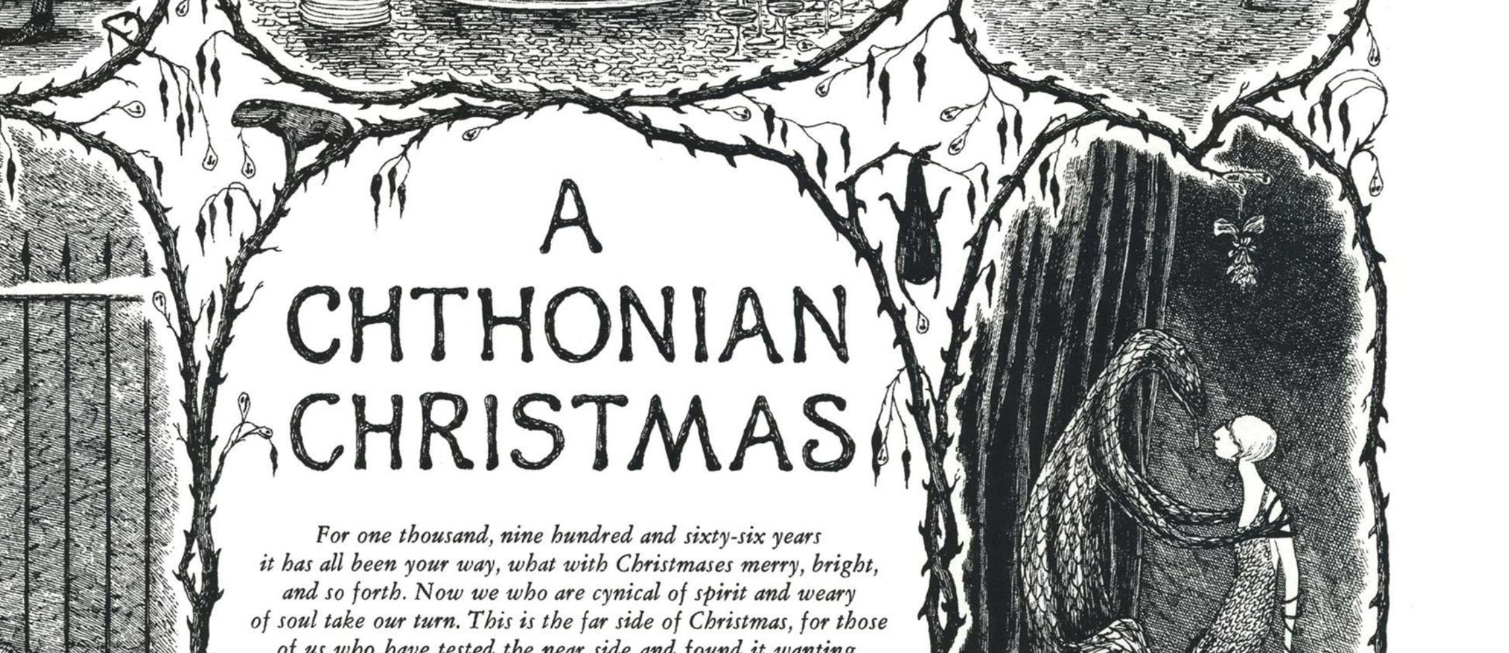

Two young men, wrapped as gifts. They have wrapped themselves carefully, tight pants, open-throated shirts, shoes with stacked heels, gold jewelry on right and left wrists, codpieces stuffed with credit cards. They stand, under a Christmas tree big as an office building, the women rush toward them. Or they stand, under a Christmas tree big as an office building, and no women rush toward them. A voice singing inappropriate Easter songs, hallelujahs.

Two young men, artists, naked in a loft on Broome Street, are painting a joint portrait of four young women, fully clothed, who are standing in a row with their backs to the artists, who are sipping coffee from paper cups (the paper cup held in the left hand, the brush or palette knife in the right) and carefully regarding the backs of the women, who from time to time let slip from the sides of their mouths comments (encouraging or disparaging) about the artists, who for their part are not intimidated by these comments which have mostly to do with the weather and future projects but in some cases with the comparative beauty and masculinity (because of course the women have opinions about these matters, expressed in whispers just loud enough to be overheard) of the naked artists, who are mostly worried about the stamina and comfort (four or five hours’ work yet ahead) of the women, who are feeling rather hot and peevish in the white-painted, rather stuffy (although the big windows have been opened) loft of the artists, who are perfectly comfortable themselves, being naked, but do recognize the fact that some discomfort may be engendered by the heavy overcoats worn by the women, who are in truth pulling and tugging irritably upon these gross garments, increasing the nervousness of the artists, who are also concerned about the effect the scene might have upon someone who just blundered into it, such as the four lovers of the women, who are thinking now (by coincidence) of those selfsame lovers, Luke, Matt, John, and Mark, and what they might say if, battered by the heat of the hot sun, they staggered into an air-conditioned art gallery and there beheld a sixteen-by-forty foot painting of four backs, backs that they know intimately even through the layers of clothes, and begin to wonder whether the clothes on those backs had just been painted on (but of course they had been painted on, like everything else on the canvas) but had been really there while the women were posing for the naked artists, who are as character types notoriously . . .

Nowhere — the middle of it, its exact center. Standing there, a telephone booth, green with tarnished aluminum, the word PHONE and the system’s symbol (bell in ring) in medium blue. Inside the telephone booth, two young women, one dark, one fair, facing each other. Their breasts and thighs brush lightly (one holding the receiver to the other’s ear) as they place phone calls to their mothers in California and Maine. In profile to the scene, at far right, Henry James, wearing white overalls.

Henry James, wearing white overalls (Iron Boy brand) is attending a film. On the screen two young women, naked, are playing ping-pong. One makes a swipe with her paddle at a ball the other has placed just over the net and misses, bruising her right leg. The other puts down her paddle and walks around the table (gracefully) to examine the bruise; she places her hands on either side of the raw, ugly mark, then bends to kiss it. Henry James picks up his hat and walks thoughtfully from the theatre. Behind the popcorn machine in the lobby stand two young women, naked, one dark and one fair. Henry James approaches the popcorn stand and purchases, for 35¢, a bag of M & Ms. He opens the bag with his teeth. The women smile at each other.

Two young women wearing web belts to which canteens are attached, nothing more, marching down Broadway again. They are followed by a large crowd, bands, etc.

A plaza or open space. Two young women on their hands and knees. They are separated by a distance of eight feet, both facing in the same direction. Rough wooden boards (one by tens) have been laid across their backs to form a sort of table. On top of the table are piled bags and bags of M & Ms, hundreds of bags some of which have been opened spilling the chocolate out onto the table. A small army of insects, not ants but other chocolate-loving insects, informed of this prime target by scouts, is advancing across the plaza toward the rear of the table. The vanguard (the insects are a half-inch long and, closely inspected, resemble tiny black toothbrushes) reaches the left leg of the young woman on the left side of the table. The boldest members leap upon the leg, a line of insects runs up the leg toward the cleft of the buttocks. The table shudders and collapses.

The world of work. Two young women, one dark, one fair, wearing web belts to which canteens are attached, nothing more. They are sitting side-by-side on high stools (OO OO) before a pair of draughting tables, inking-in pencil drawings. Or, in a lumberyard in Southern Illinois, they are unloading a railroad car containing several hundred thousand board feet of Southern yellow pine. Or, in the composing room of a medium-sized Akron daily, they are passing long pieces of paper through a machine which deposits a thin coating of wax on the back side, and then positioning the type on a page. Or, they are driving two Yellow cabs which are racing side-by-side up Park Avenue with frightened passengers, each driver trying to beat the other to a hole in the traffic in front of them. Or, they are seated at adjacent desks in the beige-carpeted area set apart for officers in a bank (possibly the very same bank they had entered, naked, masked, several days ago), refusing loans. Or, they are standing bent over, hands on knees, peering into the site of an archaeological dig in the Cameroons. Or, they are teaching, in adjacent classrooms, Naked Physics — in the classroom on the left, Naked Physics I, and in the classroom on the right, Naked Physics II. These courses are very popular. Or, they are kneeling, sitting on their heels, before a pair of shoeshine sta

nds, polishing the expensive boots, suave loafers, of their admiring customers. OO OO.

Two women, one dark and one fair, wearing parkas, blue wool watch caps on their heads, inspecting a row of naked satyrs, hairy-legged, split-footed, tailed and tufted, who hang on hooks in a meat locker where the temperature is a constant 18 degrees. The women are tickling the satyrs under the tail, where they are most vulnerable, with their long white (nimble) fingers tipped with long curved scarlet nails. The satyrs squirm and dance under this treatment, hanging from hooks, while other women, seated in red plush armchairs, in the meat locker, applaud, or scold, or hug and kiss, in the meat locker.

Two women, one dark and one fair, wearing parkas, blue wool watch caps on their heads, inspecting a row of naked young men, hairy-legged, many-toed, pale and shivering, who hang on hooks in a meat locker where the temperature is a constant 18 degrees. The women are tickling the young men under the tail, where they are most vulnerable, with their long white (nimble) fingers tipped with long curved scarlet nails. The young men squirm and dance under this treatment, hanging from hooks, while giant eggs, seated in red plush chairs, boil.

Two young women, naked, trundle the giant boiled eggs to market in wheelbarrows. They move through double rows of shouting civilians who applaud the size, whiteness, and exquisite shape of the eggs, and the humor and good cheer of the women. The grandest eggs ever seen in this part of the country, and the most gloriously-powered wheelbarrows! There is no end to the intoxicating noise. The women are sweating, moisture visible on their backs, on their legs and breasts, on their white, beautifully-formed shoulders. Yet they smile, and smile, and smile, their hands on the handles of the wheelbarrows, their sturdy sweating backs bent into the work. Like Henry James writing a novel, they trundle onward, placing one foot in front of the other in sweet, determined, dogged bliss — the achievement of a task.

Bliss: A condition of extreme happiness, euphoria. The nakedness of young women, especially in pairs (that is to say, a plenitude) often produces bliss in the eye of the beholder, male or female. If you have an elbow in your mouth, then you are occupied, for the moment, but your mind often wanders away, toward more bliss, wondering if you should be doing something else, with your arms and legs, so as to provide more static along the surface of the situation, wherein the two (naked) young women lie unfolded before you, waiting for you to fold them up again in new, interesting ways. Oh they are good kids, no doubt about it, and brave and forthright too, and mind their manners and their eggs, and have hope and ambitions, and are supportive and giving as well as chilly and austere — most of all, naked. That is a delight, let us confess the fact, and that is why we are considering all these different ways in which naked young women may be conceptualized, in the privacy of our studies, dealt out like cards from a deck of thin, flexible, six-foot-tall mirrors. Doubtless women do the same sort of thing in regard to us, in the privacy of their studies, or even better things, things we have not yet been able to imagine, or possibly nothing at all — maybe they just sit there, the beauty of a naked thumb, for example, or a passionate, interestingly-historied wrist. What if they don’t care? If this is the case, send them to the elephants, let them sit around all day listening to the elephants cry “Long live King Babar! Long live Queen Celeste!” Few naked young women can take much of this.

Back to business: Two naked young women are walking, with an older man in a white suit, on a plain in British Columbia. The older man has told them that he is Henry James, returned to earth in a special dispensation accorded those whose works, in life, have added to the gaiety of nations. They do not quite believe him, yet he is stately, courteous, beautifully-spoken, full of anecdotes having to do with the upper levels of London society. One of the naked young women reaches across the chest of Henry James to pinch, lightly, the rosy, full breast of the second young woman, who —