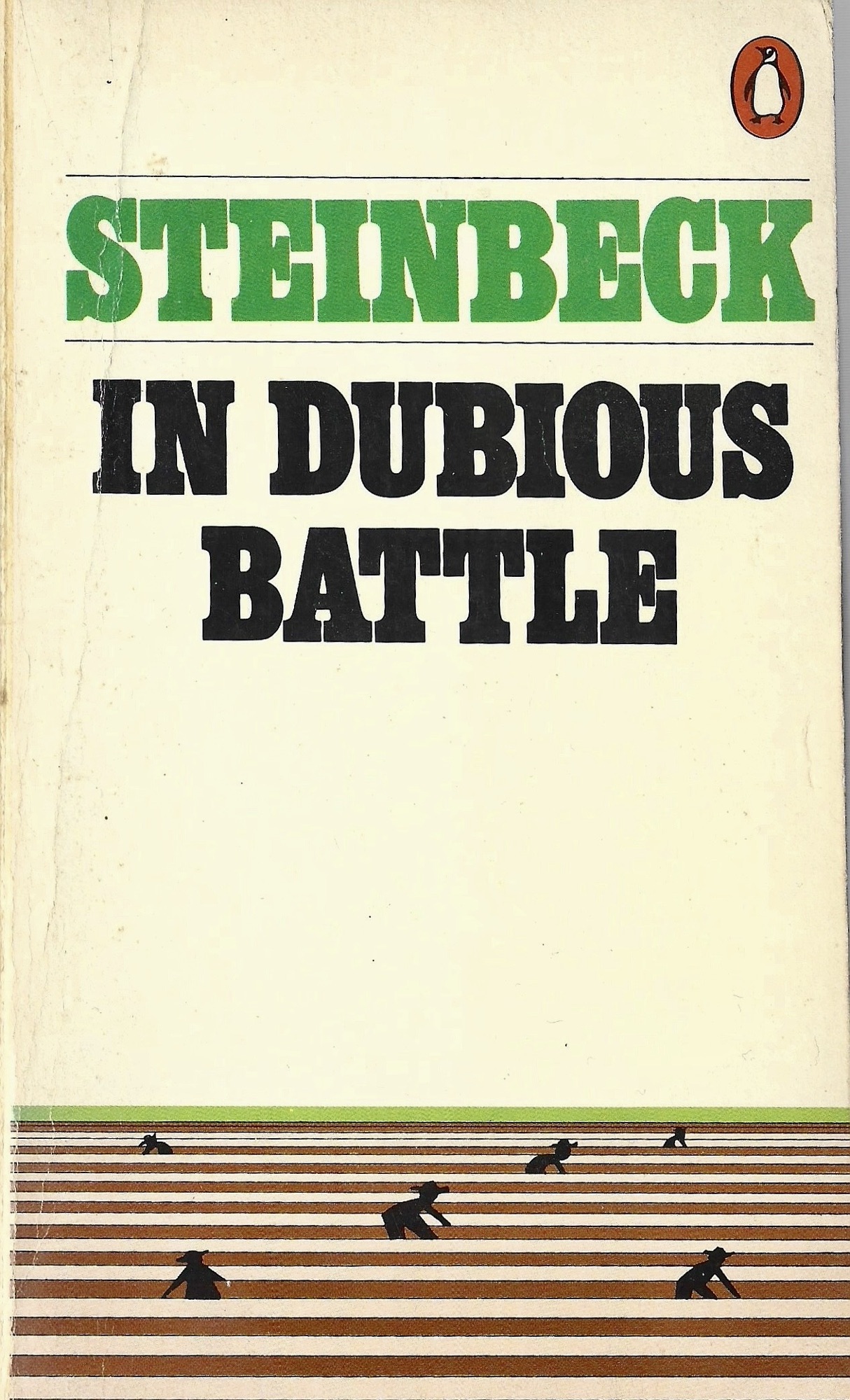

“The Plug,” by Stephen Dixon, was published in the winter 1997 issue of Rain Taxi.

I did a coupla readings for my last novel, Gould, and at one of them a guy in the audience said “Were you influenced by Thomas Bernhard?” and I said “Why, because of the long paragraphs? To tell you the truth, I know he has a great reputation but I started two Bernhard books and I didn’t think he did the long paragraph that well. They were repetitive, a bit formally and almost too rigidly written, and I often lost track of the story in them, and other things why I didn’t like them, although what, I forget.” “No,” he said, “or maybe that, but also because Gould is a character in one of his books too, The Loser. I just thought it was too much of a coincidence that you hadn’t read a lot of him and been influenced,” and I said “Gould? That guy’s name in his book is Gould? I thought I made up that forename,” and he said “Glenn Gould,” and I said “No, my character is Gould Bookbinder and he doesn’t play the piano though I think he does love Bach above all composers and especially the composition Gouldberg Variations,” and he said “That’s another thing. The first part of your novel is about variations of a single theme, abortions, right?–or that’s what you said,” and I said, “So, another coincidence. But you made me interested; I’ll read The Loser.” I didn’t, though, but a month later a colleague of mine asked if I’d ever read Bernhard’s The Loser and I said “Why, because of the long paragraphs, though he only seems to have one paragraph a book, and because of the name Gould, though I don’t know if you know–” and she said “I do: first name, not last name. But I was thinking you’d like him. The two of you do a lot of the same things. The urban settings, dark but comical nature of your characters, their dislike of so many things, though your narrators for the past ten years of your work have been fathers to the extreme as well as loyal husbands, while none of his main characters seem to have children and they never marry either or have sex, at least not in the books,” and I said “This is a double coincidence, your bringing up The Loser and someone at a recent reading bringing it up, or maybe ‘coincidence’ isn’t the right word. And sure, I understand it: Gould, the name, and my love for losers, and the long paragraph, so I’m going to read that book, I promise; the next book I start will be The Loser.” “What’re you reading now?” she said and I said “I forget; what am I reading now? It can’t be too interesting if I don’t know what it is. It isn’t interesting, in fact, so I’m going to buy a copy of his book today.” Usually I put things like this off, or just forget it, but this time I didn’t. I have to have a book to read and The Loser sounded like the one, but more out of curiosity, which isn’t a good reason for me to read a book, than because I was interested in it as literature. So I bought it that day, started it that night, and loved it. There’s my literary criticism. The single paragraph worked. So did Glenn Gould as a supporting character and Horowitz in the background. The book was funny and deep and crabby and dark and obsessive. He had his Gould and I had mine and the coincidence of the two of us using the same name, though his last but first and mine first but second, and intrigued, maybe for the same reason–I don’t know what his is but mine is that I can’t write anything anymore but in a single paragraph–by the long paragraph is, well . . . I lost my thought and apologize for the disarray. I liked it because it was intelligent, or should I say “I also liked it because,” and it was short, though took me a long time to finish, relatively speaking, since my eyes aren’t what they used to be and eyeglasses don’t do what they used to do for me and my body gets tireder faster than it used to and after a long day of work, and every day seems to be a long day of work, only a little of it my writing, I don’t have that much time to read the book, which is the only way I like to read: I want to read it, I want to read him. And after I read it I wanted to immediately read another Bernhard book, that’s the effect the first one had, so I got Woodcutters and read that and loved it and thought it was better than The Loser, funnier, crabbier, darker, more opinionated and artistic, he did things in this he didn’t in the other, trickier literary things: the guy sitting in the chair three quarters of the book, never getting out of it, just observing and thinking about what he observes, like someone out of Beckett’s novels but better, though Bernhard must have lifted it from Beckett, at least spiritually–do I know what I’m saying? Let me just say there was a very Beckettian feeling about Woodcutters. Anyway, after that one I immediately got another one, Yes, and didn’t much like it–it was older Bernhard, early Bernhard, it didn’t take the risks, it didn’t compel me to read, and it had paragraphs, I think, and I got The Lime Works and it was only so-so, and I thought “Have I read the very best of Bernhard or is it that his later works are better than his early ones?” and so got Old Masters, one of the last books of Bernhard, I think, and thought that the best one, again the man sitting in a chair, though it’s a couch in a museum, and it was even more vitriolic than Woodcutters, and next immediately read Concrete and thought that a very good one and I’m now reading Correction and liking it and I will probably read The Cheap-Eaters, without even thinking “early, late, middle Bernhard,” what do I care anymore? I just want to continue to read the guy, though a German professor at Hopkins where I teach told me there are more than twenty Bernhard novels, not all of them translated but all of them to be translated, and I told her maybe that’ll be too many for me to read, but you never know. I asked this woman “By the way, this Austrian writer Stifter, he mentions in Old Masters, he’s not a real person, is he?” and she said “Oh yes, very famous, a traditionalist, not too well known in America,” and I said “Amazing what Bernhard gets away with. Imagine an American writer working into his texts such excoriations of other writers, including contemporaries, which Bernhard does too. And knocking the Academy and prize givers, as Bernhard does in almost all his books: in America writers claw each other to get prizes and, you know, throw up on the hands that pin the medals on their chests and stuff the checks into their pockets. Some of his thoughts are a bit odd and wrongheaded if not occasionally loony,” I said, “but most I agree with. And after reading a lot of him, in addition to all the other similarities people have mentioned–well, really, just two people–and I don’t think the first ever read my work, just picked it up from the reading I gave and what was on the book jacket–is . . . oh, I forget what I was going to say.” I want to end this by saying I haven’t been so taken by one writer since I was in my mid-twenties and started reading everything Saul Bellow had written up till then. And in my early twenties, I read one Thomas Mann book after the other, probably not completing his entire oeuvre but getting close. And before that, when I was eighteen, I read everything of Dostoevski’s that had been translated. And I forgot Joyce and my mid-twenties when I read everything he wrote, though his corpus wasn’t by any means as large as Mann’s or Dostoevski’s. And one last note: Please don’t think I’m writing this as a plug for my own Gould. Or that what I just said in that last sentence is an additional plug. I hate writers who plug their books, who sort of work in a reference to their books, especially the new ones, whenever they can. I only brought up my book because it’s consequential to this inconsequential minor essay on Bernhard and that if I hadn’t written a book called Gould I probably wouldn’t have read The Loser and, of course, after that, another half-dozen Bernhard books. Did I use “inconsequential” right, then? Perhaps even to call this an essay is absurd, though to call it inconsequential and minor isn’t. But I hope I just did what I always like to do and that’s to belittle my own work and show myself as a writer who’s part bumbling semimoron. And also done what I’ve never done in print before, so far as I can remember, and my memory isn’t that good, and that is to plug the work of someone else and write even in the most exaggerated definition of the word an essay. “Exaggerated” isn’t the word I meant, I think, but I’m sure you know what I mean even in my probable misuse of it.

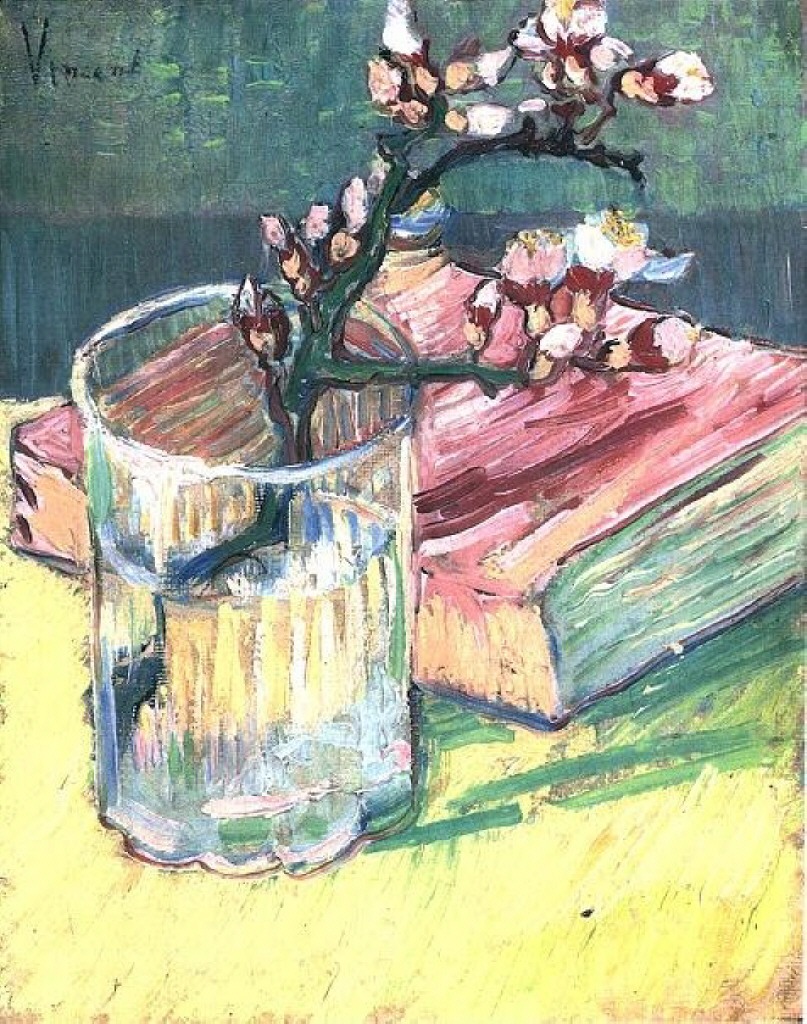

Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book, 1888 by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book, 1888 by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)