We’ll be running a giveaway contest for one of these beautiful editions of Hoffman’s Nutcracker, featuring illustrations by Maurice Sendak sometime next week.

We’ll be running a giveaway contest for one of these beautiful editions of Hoffman’s Nutcracker, featuring illustrations by Maurice Sendak sometime next week.

This one looks pretty cool—Reprobates, John Stubbs’s history of the English Civil War. A cursory flip through the book suggests that the subtitle is perhaps a little misleading—Reprobates seems to be more of a survey of the shifts in English culture in the 17th century than a dry study of the actual war between Roundheads and Royalists. In his insightful review at Literary Review, Adrian Tinniswood points out that,

. . . the real focus of Stubbs’s book is the cavalier poets, that motley collection of royalist writers who gathered around the aging and irascible Ben Jonson in the late 1620s and 1630s and went on to seek their fortunes at court, simultaneously memorialising and mythologising its decline. The self-styled ‘Tribe of Ben’ – William Davenant, Thomas Carew, Sir John Suckling and the rest – remain resolutely minor figures, both in literature and in history. Most are remembered for a single poem, like Sir John Denham and ‘Cooper’s Hill’, or even a single line, like Richard Lovelace’s ‘Stone walls do not a prison make’ or Robert Herrick’s ‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may’. Some aren’t even remembered for that. Can you recall anything Suckling wrote? . . . Under Stubbs’s affectionate but forensic gaze these reprobates seem like figures of fun in a Restoration comedy rather than the heroes they so clearly believed themselves to be.

At The Guardian, Christopher Bray finds even more comedy in these reprobates, suggesting that,

If Ben Elton ever writes another series of Blackadder, Reprobates ought to be top of his research list. Not because John Stubbs offers a daringly revisionist take on the English civil war. The book’s subtitle notwithstanding, the war occupies rather fewer than a quarter of its nearly 500 pages. What we do get, though, is a colourful braiding of poetry criticism, literary biography and social and political history – the whole lot knotted together by characters of such effervescent high spirits the sitcom form might have been invented for them.

Looks like good stuff.

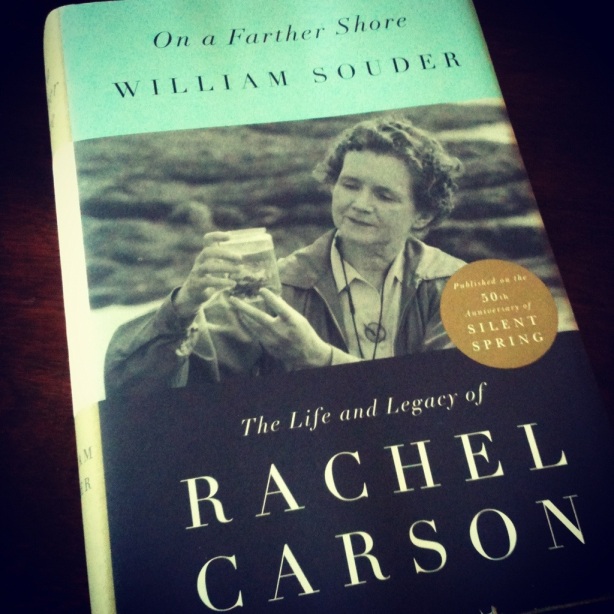

On a Farther Shore is William Souder’s big, bold biography of Rachel Carson, whose long (and often poetic) essay Silent Spring changed the way many people thought about humanity’s changing relationship with the environment. Here’s publisher Crown/Random House’s blurb:

She loved the ocean and wrote three books about its mysteries, including the international bestseller The Sea Around Us. But it was with her fourth book, Silent Spring, that this unassuming biologist transformed our relationship with the natural world.

Rachel Carson began work on Silent Spring in the late 1950s, when a dizzying array of synthetic pesticides had come into use. Leading this chemical onslaught was the insecticide DDT, whose inventor had won a Nobel Prize for its discovery. Effective against crop pests as well as insects that transmitted human diseases such as typhus and malaria, DDT had at first appeared safe. But as its use expanded, alarming reports surfaced of collateral damage to fish, birds, and other wildlife. Silent Spring was a chilling indictment of DDT and its effects, which were lasting, widespread, and lethal.

Published in 1962, Silent Spring shocked the public and forced the government to take action-despite a withering attack on Carson from the chemicals industry. The book awakened the world to the heedless contamination of the environment and eventually led to the establishment of the EPA and to the banning of DDT and a host of related pesticides. By drawing frightening parallels between dangerous chemicals and the then-pervasive fallout from nuclear testing, Carson opened a fault line between the gentle ideal of conservation and the more urgent new concept of environmentalism.

Elegantly written and meticulously researched, On a Farther Shore reveals a shy yet passionate woman more at home in the natural world than in the literary one that embraced her. William Souder also writes sensitively of Carson’s romantic friendship with Dorothy Freeman, and of her death from cancer in 1964. This extraordinary new biography captures the essence of one of the great reformers of the twentieth century.

Elizabeth Royte gave Shore a good review in The New York Times; excerpt:

Souder is at his best when he places Carson’s intellectual development in context with the nascent environmental movement. The storm over “Silent Spring,” he notes, was a “cleaving point” in history when the “gentle, optimistic proposition called ‘conservation’ began its transformation into the bitterly divisive idea that would come to be known as ‘environmentalism.’” (Souder isn’t shy about expressing his own disappointment with what he views as a permanent wall between partisans, with nature and science pitted against an “unbreakable coalition of government and industry, the massed might of the establishment.”)

I’ll let Lucy have the last word:

The kind people of Paris Press were good enough to send me a reader copy of their 10th anniversary edition of Virginia Woolf’s essay “On Being Ill,” which they’ve collected with “Notes from Sick Rooms,” an essay by Julia Stephen—Woolf’s mother. Paris Press’s blurb:

Published together for the first time, Woolf and Stephen create a literary conversation between parent and child, patient and care giver, from the vantage points each experience in the world of illness. Originally published by Paris Press in 2002, this new edition doubles the length of the original book and includes a new introduction to Notes from Sick Rooms by eminent Woolf scholar Mark Hussey, and a new afterword by Rita Charon, founder and director of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University, along with the original introduction to On Being Ill by Hermione Lee, Woolf’s biographer.

Lee’s introduction seems to be an expansion of a piece she wrote for The Guardian in 2004; in that piece she wrote:

The story of the body’s life, and the part the body has to play in our lives, is one of Virginia Woolf’s great subjects. Far from being an ethereal, chill, disembodied writer, she is always transforming thoughts and feelings and ideas into bodily metaphors. She writes with acute – often extremely troubling – precision about how the body mediates and controls our life stories. Body parts are strewn all over her pages. Rage and embarrassment are felt in the thighs; a headache can turn into a whole autobiography; dressing up the body is an epic ordeal; and a clenched fist, feet in a pair of boots, the flash of a dress or the fingertip feel of a creature in a salt-water pool, can speak volumes.

Nowhere is her attention to body parts more eloquent and intense than in the essay “On Being Ill”. It is one of Woolf’s most daring, strange and original short pieces of writing, and it has more subjects than its title suggests. Like the clouds that its sick watcher, “lying recumbent”, sees changing shapes and ringing curtains up and down, this is a shape-changing essay.

Woolf announces her theme in a long, winding opening sentence that showcases some of the “shape-shifting” Lee alludes to:

Considering how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us by the act of sickness, how we go down in the pit of death and feel the waters of annihilation close above our heads and wake thinking to find ourselves in the presence of the angels and the harpers when we have a tooth out and come to the surface in the dentist’s arm-chair and confuse his “Rinse the mouth-rinse the mouth” with the greeting of the Deity stooping from the floor of Heaven to welcome us – when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.

And what of Stephen’s essay? It’s a practical, concrete, and mostly pragmatic approach to caring for sick people. Some parts compel more than others, as when Stephen discusses the absurd flights of fancy that might afflict the ill. In his introduction to “Notes from Sick Rooms,” Mark Hussey tries to amplify connections between the two texts that are either obvious (the texts share a common subject) or speculative (Stephen’s essay “foreshadows the wit and sharp observation that is characteristic of her famous daughter’s style”). Hussey’s comments are best when they provide basic context and don’t try to force the reader into making connections. There’s also an afterward by Rita Charon, an internist, who again tries to synthesize the two texts. I suppose context is important, but there’s a sense of inflation here that I’m not entirely sure either essay (Woolf’s or Stephen’s) necessarily merits.

I took my kids to the book store today and let them run like heathen.

They had fun. I usually take them separately (and usually they go to the library), but their mother is at work and we needed to get out of the house.

My daughter picked out a few books for her little brother (and then read them to him, sort of).

She also picked out a book of antique paper dolls (Dolly Dingle) and an Anne of Green Gables pop up cottage book to let the dolls live in.

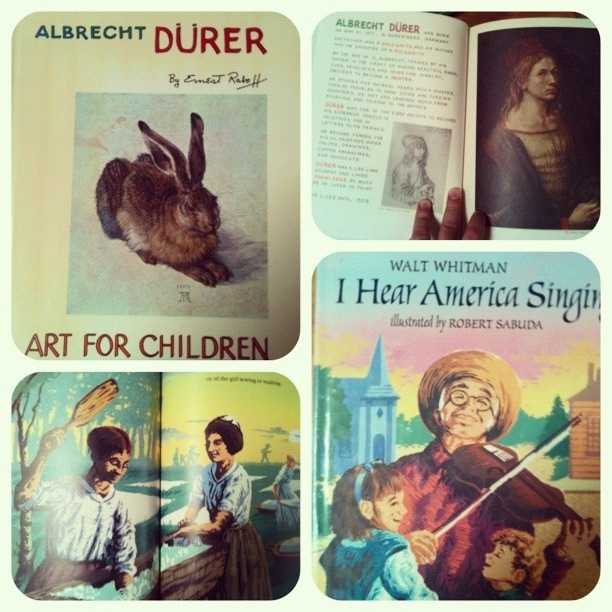

Here’s what I picked out, maybe more for me than them:

A beautiful illustrated Durer biography that’s written more or less like a comic book, and an illustrated edition of Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing.”

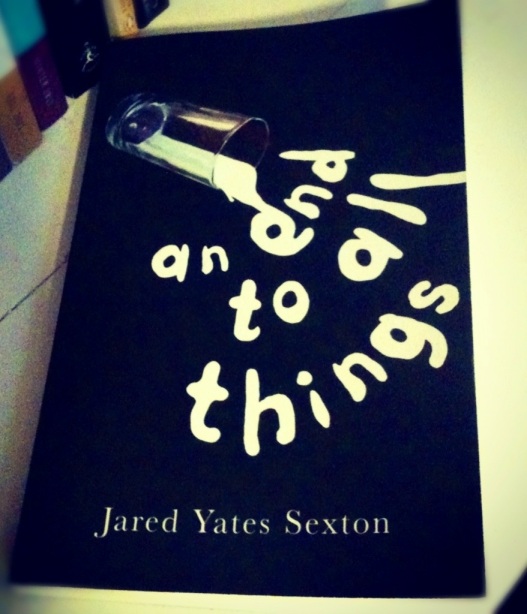

Jared Yates Sexton’s An End to All Things immediately appealed to me when it arrived last month. This collection is stocked with short, precise, unpretentious stories. Great sentences—shades of Hannah, Carver, Pancake. I’ve read about half a dozen so far, parceling them out over spare afternoon minutes and it’s good stuff—feels real without the strains of literary realism. You can read a story at publisher Atticus Books’ site, “You Never Ask Me About My Dreams” (great title). The first few paragraphs:

At that point things had been rough for a couple of months and I would’ve done anything to ease the tension. I set an alarm for half an hour earlier than usual. I thought if I had some breakfast going when Cathy got up she’d have to see that I cared.

After all, cooking wasn’t the easiest thing to do in our house. Both of us hated dishes so the kitchen was always a mess. There were pots and pans stacked on the counters and plates in the sink. Some still had clumps of food stuck to them. I even had to rinse out a bowl to use. Somehow there were a couple of clean forks and knives in the drawer. I got some eggs from the fridge and went to work scrambling the yolks.

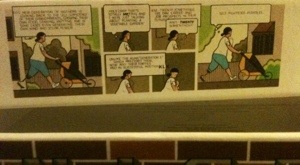

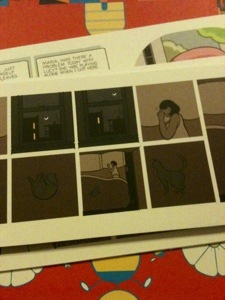

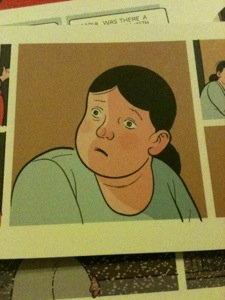

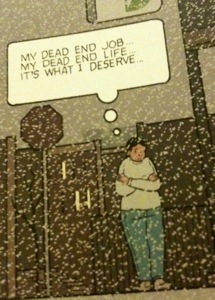

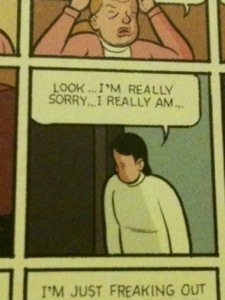

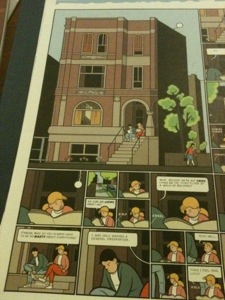

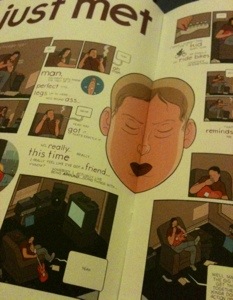

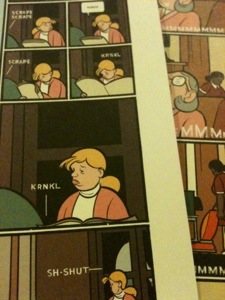

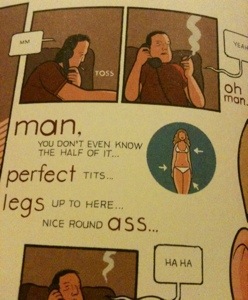

For some reason—some reason founded on no reason at all but rather superstitious suspicion—I didn’t believe Charles Burns would follow up X’ed Out, the first chapter of a proposed trilogy. I suppose X’ed Out had unresolved cult classic written all over it (written metaphorically, of course).

X’ed Out was one of my favorite books of 2010. From my review:

In Black Hole, Burns established himself as a master illustrator and a gifted storyteller, using severe black and white contrast to evoke that tale’s terrible pain and pathos. X’ed Out appropriately brings rich, complex color to Burns’s method, and the book’s oversized dimensions showcase the art beautifully. This is a gorgeous book, both attractive and repulsive (much like Freud’s concept of “the uncanny,” which is very much at work in Burns’s plot). Like I said at the top, fans of Burns’s comix likely already know they want to read X’ed Out; weirdos who love Burroughs and Ballard and other great ghastly fiction will also wish to take note. Highly recommended.

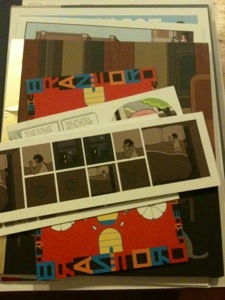

So, of course I was stoked when Burns’s sequel The Hive showed up a few weeks ago—in fact, the only thing that got in the way of me reading it immediately was that it showed up in a package along with Chris Ware’s Building Stories (this is, without question, the best package I’ve received in six years of doing the blog).

Anyway, I’ll be revisiting X’ed Out and then reviewing The Hive in the next week or so. For now, a few pics. Two from the interior above. And our hero Doug, in his alter-ego/costume Nitnit (inverse Tintin):

I dig this panel in particular: A take on Roy Lichtenstein via Raymond Pettibon via the romance comics those pop artists were riffing on:

I got a copy of Kirby Gann’s novel Ghosting a few week or so ago, and finally have had time to dip into the first three chapters this morning. Gann’s prose—and perhaps the framing of his characters—reminds me a bit of Russell Banks or Thomas McGuane—that combination of the rough and the refined, that rawness that actually comes from meticulous reworking. Sample of that prose (context not important):

The first cop to show nods at Dwayne Hardesty and stands beside him at the feet of four kids who lie spread-eagled face-down on the muddy portico steps leading to the graffiti-strewn boards that shield the seminary entrance. The wash of the cruiser’s spot frescoes their captive forms in hard outline, three underfed and thin and the fourth a fat block squeezed into a Kentucky basketball sweatshirt that strains to withstand his heavy nervous breathing, the grommets in their jeans and an occasional earring flashing agleam in the white light; four pairs of white sneakers, expensive and rain-wet, shine stark and severe and unworldly.

Ghosting is a thriller, and Gann propels the narrative forward with these cinematic images (and realistic dialogue), engaging the reader to keep turning the pages.

Here’s the jacket copy:

A dying drug kingpin enslaved to the memory of his dead wife; a young woman torn between her promising future and the hardscrabble world she grew up in; a mother willing to do anything to fuel her addiction to pills; and her youngest son, searching for an answer behind his brother’s disappearance—these are just some of the unforgettable characters that populate Ghosting, Kirby Gann’s lush and lyrical novel of family, community, and the ties that can both bond and betray.

Fleece Skaggs has disappeared along with Lawrence Gruel’s reefer harvest. Convinced that the best way to discover the fate of his older brother is to take his place as a drug runner for Greuel, James Cole plunges into a dark underworld of drugs, violence, and long hidden family secrets, where discovering what happened to his brother could cost him his life.

A genre-subverting literary thriller explored through the alternating viewpoints of different characters, Ghosting is both a simple quest for the solution to a mystery, and a complex consideration of human frailty and equivocation.

In the House of the Interpreter is a memoir from Ngugi wa Thiong’o. It’s new next month in hardback from Pantheon (lovely cover/design, on this one, Pantheon people. Seriously). Their blurb:

World-renowned Kenyan novelist, poet, playwright, and literary critic Ng˜ug˜ý wa Thiong’o gives us the second volume of his memoirs in the wake of his critically acclaimed Dreams in a Time of War.

In the House of the Interpreter richly and poignantly evokes the author’s life and times at boarding school—the first secondary educational institution in British-ruled Kenya—in the 1950s, against the backdrop of the tumultuous Mau Mau Uprising for independence and Kenyan sovereignty. While Ng˜ug˜ý has been enjoying scouting trips, chess tournaments, and reading about the fictional RAF pilot adventurer Biggles at the prestigious Alliance High School near Nairobi, things have been changing rapidly at home. Poised as he is between two worlds, Ng˜ug˜ý returns home for his first visit since starting school to find his house razed and the entire village moved up the road, closer to a guard checkpoint. Later, his brother Good Wallace, a member of the insurgency, is captured by the British and taken to a concentration camp. As for Ng˜ug˜ý himself, he falls victim to the forces of colonialism in the person of a police officer encountered on a bus journey, and he is thrown into jail for six days. In his second year at Alliance High School, the boarding school that was his haven in a heartless world is shattered by investigations, charges of disloyalty, and the politics of civil unrest.

In the House of the Interpreter hauntingly describes the formative experiences of a young man who would become a world-class writer and, as a political dissident, a moral compass to us all. It is a winning celebration of the implacable determination of youth and the power of hope.

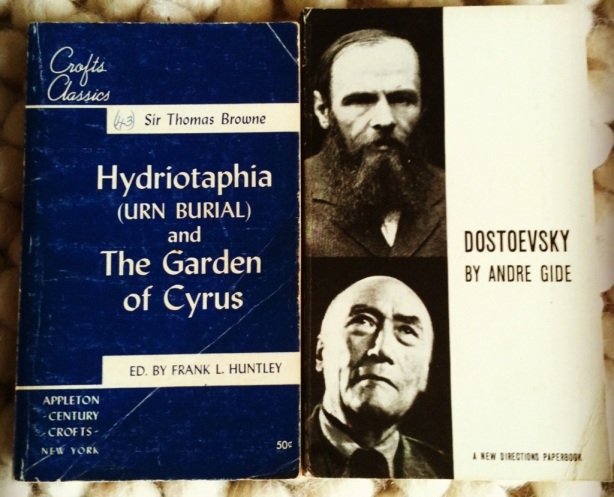

Needing more books like I need another hole in my head, I nevertheless visited my local bookshop (after an impressive three week abstinence period).

No, I haven’t read Thomas Browne’s Urn Burial yet. I’m a sucker for New Directions’ back stock, I just finished Crime & Punishment, and Gide’s book looks cool. Plus it was like a dollar.

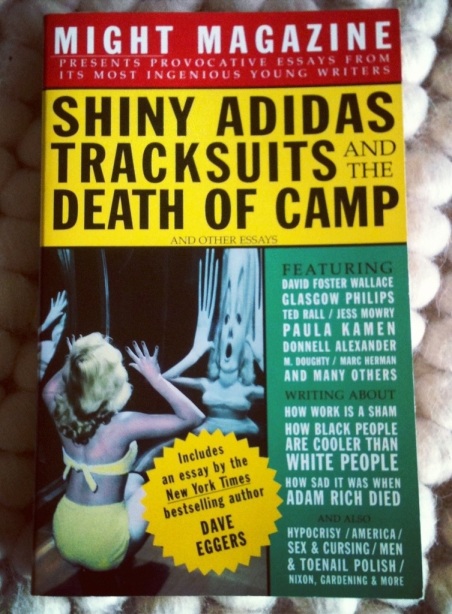

I spied the Might Magazine collection—I knew Might as Dave Eggers’s first venture. I picked it up for the (very short) David Foster Wallace essay “Hail the Returning Dragon, Clothed in New Fire”—which, incidentally, doesn’t appear to be is collected in the forthcoming collection Both Flesh and Not under the new not-as-Game of Thronesish title “Back in New Fire.”

I guess these books are already big in the UK, or maybe they will be big, or something. This one’s an ARC and it doesn’t come out until early next year. Here’s the UK pub copy:

Hired by Tommy Ordonez, the richest man in the Philippines, to recover $50 million in a land swindle, Ava has her work cut out. Tommy’s brother has messed up and the Filipino billionaire’s reputation is on the line.

Tracking the money, Ava uncovers an illegal online gambling ring, and follows the trail to Las Vegas. Once there, she turns her gaze to David Douglas, one of the greatest poker players in the world – and someone who knows more about the missing money than he’s letting on.

Meanwhile, Jackie Leung, an old target of Ava’s, has made it rich. He wants revenge, and he’s going after Ava.

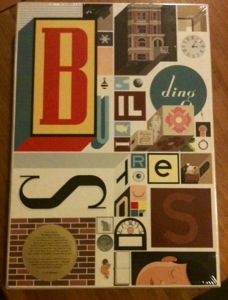

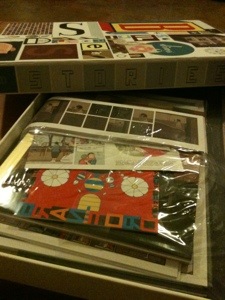

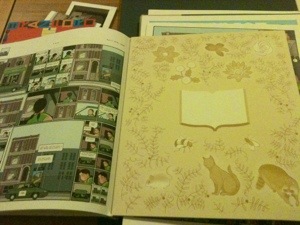

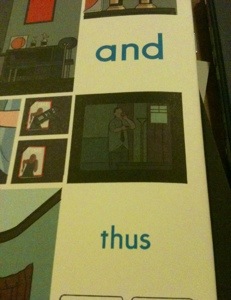

Thrilled today to get Building Stories, Chris Ware’s latest.

Thrilled here is no hyperbole—I can’t remember being so excited to open a book in quite some time.

But Building Stories isn’t really a book.

First, it comes in this big box—like a board game.

Here:

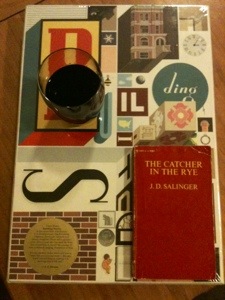

I show it set against The Catcher in the Rye in mass market paperback and a glass of red.

(The Catcher in the Rye + glass of red is the international standard for items used to show relative dimensions of size).

(Also, don’t worry about the wine ring—still shrinkwrapped at this point).

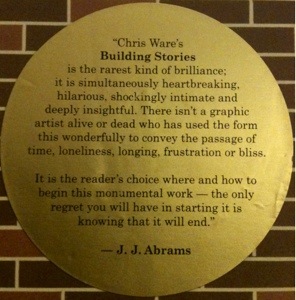

And on that shrinkwrap blazons a blurb by some guy named J.J. Abrams:

A description of the formal elements of Building Stories from the back of the box:

I open the box:

From the inside of the top of the box:

Not sure if that second quote shows here, but:

Pablo Picasso suggests that, Everything you can imagine is real.

The package:

Strips and papers and books.

Shots as I go through it:

Stack: The shorter/smaller stuff is on top—a suggestion to read it first? / Probably not.

Probably more a packing issue.

I remember a professor in grad school musing about where a book begins.

The title page?

The cover?

How and where does a book begin?

Chris Ware’s Building Stories: a kind of Möbius strip,

crammed with ideas,

illustrations,

writing,

stories . . .

Little golden book

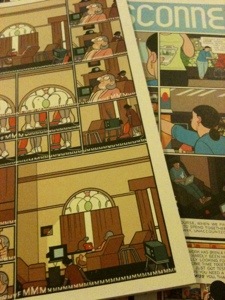

. . . and broadside.

. . . so many faces . . .

. . . layers . . .

. . . and layers . . .

Ware’s transitions:

(They always remind me of David Foster Wallace, who I know Ware read).

And thus so well . . .

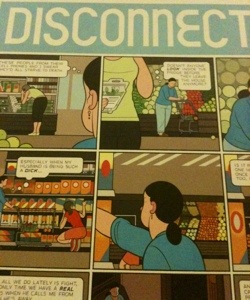

Disconnect?

Boom!

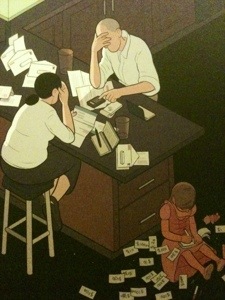

I should’ve busted out the wine glass or the Salinger here to show the scale of this marvelous painting, better than anything I’ve seen in contemporary art in ages. It tells all the story. (Wait, you (maybe) say, have you actually read the story yet?)

No.

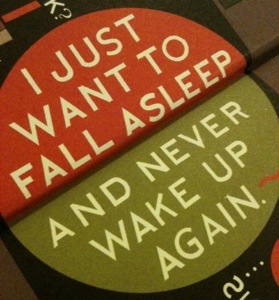

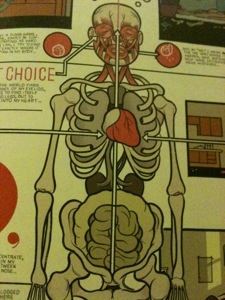

But who hasn’t felt:

And

Thus

So

Well . . .

[Insert ideas about malleability of form, sequence, narrative, idea—riff on discursive-novel-as-future-novel, etc.]

End riff/now look, read, absorb.

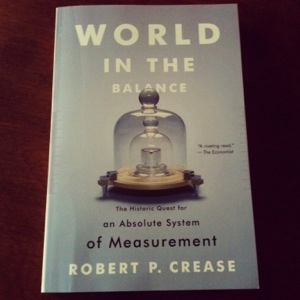

Robert P. Crease’s World in the Balance is now out in trade paperback. I wasn’t sure how interesting a book about the history of measurement could be, but when I flicked it open randomly to a chapter about Marcel Duchamp I found myself intrigued.

From Laura J. Snyder’s review at The Wall St. Journal:

‘The non-scientific mind has the most ridiculous ideas of the precision of laboratory work, and would be much surprised to learn that . . . the bulk of it does not exceed the precision of an upholsterer who comes to measure a window for a pair of curtains.” So wrote the American philosopher and scientist Charles S. Peirce (1839-1914).

Peirce may have been giving the general public more credit than he intended; most people don’t think much about the precision of scientific measurements, let alone question where the standards of measurement have come from in the past or where they are headed today. These topics are addressed by Robert P. Crease’s educational and often entertaining book, “World in the Balance.” While some readers might be put off by the episodic and occasionally repetitive structure of the book—belying its origin as the author’s columns for Physics World—those who are not will be amply rewarded with a sweeping survey of the history of measurement and the search for universal and absolute standards, from ancient China up to practically yesterday.

Camille Paglia’s latest is a gorgeous, glossy, oversized collection of essays on imagery and art. I haven’t read it in full yet, but Paglia considers an image or series of images (reproduced in full, of course), and then considers the image in a loose, riffing essay of a few short pages. She does this for almost thirty images, but I was immediately drawn to her final essay, a glowing adoration of George Lucas’s Revenge of the Sith. She had me at that moment—I’m a passionate defender of Sith, a film that navigates the tension between democracy and egotism.

Anyway, full review to come. Here’s a lousy pic of the interior (glossy pages = glare).

Publisher Pantheon’s blurb:

From the best-selling author of Sexual Personae and Break, Blow, Burn and one of our most acclaimed cultural critics, here is an enthralling journey through Western art’s defining moments, from the ancient Egyptian tomb of Queen Nefertari to George Lucas’s volcano planet duel in Revenge of the Sith.

America’s premier intellectual provocateur returns to the subject that brought her fame, the great themes of Western art. Passionately argued, brilliantly written, and filled with Paglia’s trademark audacity, Glittering Images takes us on a tour through more than two dozen seminal images, some famous and some obscure or unknown—paintings, sculptures, architectural styles, performance pieces, and digital art that have defined and transformed our visual world. She combines close analysis with background information that situates each artist and image within its historical context—from the stone idols of the Cyclades to an elegant French rococo interior to Jackson Pollock’s abstract Green Silver to Renée Cox’s daring performance piece Chillin’ with Liberty. And in a stunning conclusion, she declares that the avant-garde tradition is dead and that digital pioneer George Lucas is the world’s greatest living artist. Written with energy, erudition, and wit, Glittering Images is destined to change the way we think about our high-tech visual environment.

I was pleasantly surprised yesterday to find a big ole biography of Paul Cézanne on my doorstep. I probably won’t get to Alex Danchev’s Cézanne: A Life anytime soon (at least not until I finish Robert Hughes’s Goya bio), but it looks like a pretty solid read—with lovely glossy pictures to boot:

In the meantime, check out Evan McMurry’s full, in depth review at Bookslut.

Or, if you’re too busy, here’s the Kirkus write up in full:

A formidable biography of the Father of Modern Art bound for the annals of academia.

Danchev . . . has researched every facet and nuance of Paul Cézanne’s life (1839–1906). His comfortable childhood in Provence, his years in Paris, where he was influenced by the Impressionists, and his dependence on the allowance from his father created the artist some suggested was “not all there.” There is a wealth of information in the correspondence between the artist and his childhood friend, Émile Zola, in which they parodied Virgil, joked in Latin and discussed Stendhal. Zola knew that Cézanne’s art was a corner of nature seen through his own curious temmpérammennte. The artist didn’t paint things; he painted the effect they had on him. He saw colors as he read a book or looked at a person, understood the inner life of an object and let his brain rework that object, sometimes illuminating it, sometimes distorting it. Danchev rightly subscribes to the theory that understanding the man is important to understanding his work, and he attempts to parse Cézanne’s psyche, digging into the background of nearly every author he discussed in his letters, quoting every writer who based a character on the man. Cézanne’s work will influence artists and confuse patrons for decades to come, especially those who have the patience to study Danchev’s comprehensive, occasionally ponderous tome.

A fairly impressive achievement of a Sisyphean task—definitely a book to keep in your library.

This one is wonderfully weird stuff. Terry Richard Bazes’s Lizard World. Here’s a blurb from Grove Press founder Barney Rosset:

Lizard World opens with Josiah Fludd, a disenchanted character from the Early Modern World, exhuming a female corpse for a customer, whose interest in the carcass is presumed by the gravedigger to be a sexual one. Fludd’s blasé attitude vanishes when, on delivery of the corpse, he watches its feet sawed off, and he learns that they are meant to replace his patron’s nether claws. From this startling introduction Terry Richard Bazes pushes us into a bizarre world that vacillates between the past and present—and is told by a writer whose imagination seems to have no bounds.

Here’s an excerpt:

I being then in my nineteenth year and little more than a beggar — intent, by hook or by crook, to become a chirurgeon and yet utterly without means to feed and clothe my body (much less to learn the merest rudiments of my profession) — it came about that at length I did find a way both to earn my bread and pursue my studies by undertaking to perform a service — a wholly necessary and harmless service albeit one from which my more prosperous school-mates turned away with horror and revulsion. So it was that I got my sustenance and was suffered to sit with all the paying scholars — provided it was in the very backermost row — and watch whilst our professor probed the deepest mysteries of a fresh cadaver.

Now just exactly how and whence these cadavers were supplied were questions my finical colleagues dared not closely entertain, although in gross they knew the truth and shunned me like a leper. But I cared not a fart for their esteem, so long as I could learn, and the short of it was that I advanced quickly in my studies and was oft besought by my professors for a specimen and consequently was upon ever the most constant look-out for the newly dead.

For this purpose it was my practice to put on the clothes and countenance of a mourner and, thus disguised, to frequent the very meanest of country churches in the hope that there I might chance upon some humble obsequies. If fortune smiled, and some farmer or laundress had departed this life, then I would repair under the cloak of starlight unto the churchyard, still in mourning attire and carrying a fistful of daisies and a Bible, lest I be questioned of my purpose and require a ready pretext. The great secret of the art was to work with utmost haste and efface the smallest evidence of theft. Therefore, by the light of my lantern, I studied the disposition of each rock, each wreath of flowers — and, thus informed of the state to which the grave must later be restored, now proceeded to violate the soil, but only so much as to permit my shovel to break the very head-piece of the box. This method, once perfected, allowed me — in a trice — to draw the carcass out, conceal it in a sack, restore the injured earth, and load my stiffened burden on a waiting dung-cart.

For more excerpts, check out Bazes’s site; more to come.

Foundation, a history of England from Peter Ackroyd. From a recent Guardian profile:

Ackroyd’s trademark insight and wit, and the glorious interconnectedness of all things, permeate each page. One thing that struck me was the realisation that history isn’t nearly as linear as we thought. Something is invented, or discovered, or philosophised, and we tend to think that that’s knowledge known from then on, but even in this single volume there are endless forgettings.

“Absolutely,” comes his fast answer, spoken, as ever, gently and with a strange mix of confidence and self-effacement. “One thing which most interested me was the fact that neglect, or our genius for forgetfulness, occurs at every level of social and political activity. The same mistakes, the same confusions, occur time and time again. It sometimes seems to me that the whole course of English history was one of accident, confusion, chance and unintended consequences – there’s no real pattern.”

What he discovered, or rediscovered, is that “what underlines that random happenstance are the deep continuities of national life that survive, uninfluenced by the surface events. In this book, I have little chapters on, say, medieval medicine, or punishment, or medieval humour, simply to convey the broad continuities that underlie this bewildering range of events. Continuities of the soil, the land, the earth.” And these help create human – English – sensibilities? “Yes. As I said in my London book, it’s a sort of territorial imperative, the landscape; the shape of the geology, almost, has a definite though not comprehended effect on human behaviour, human need. So that’s one of the things I was trying to explore I suppose.”