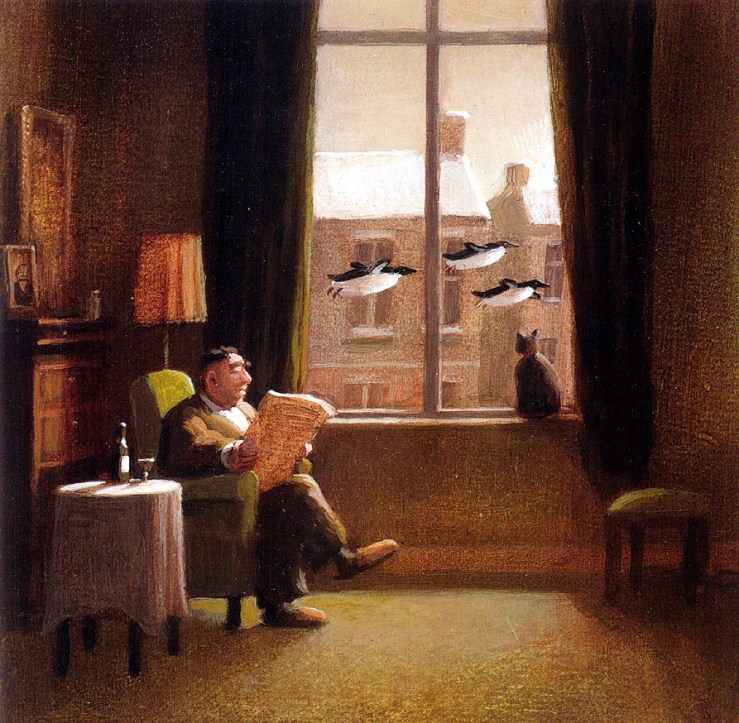

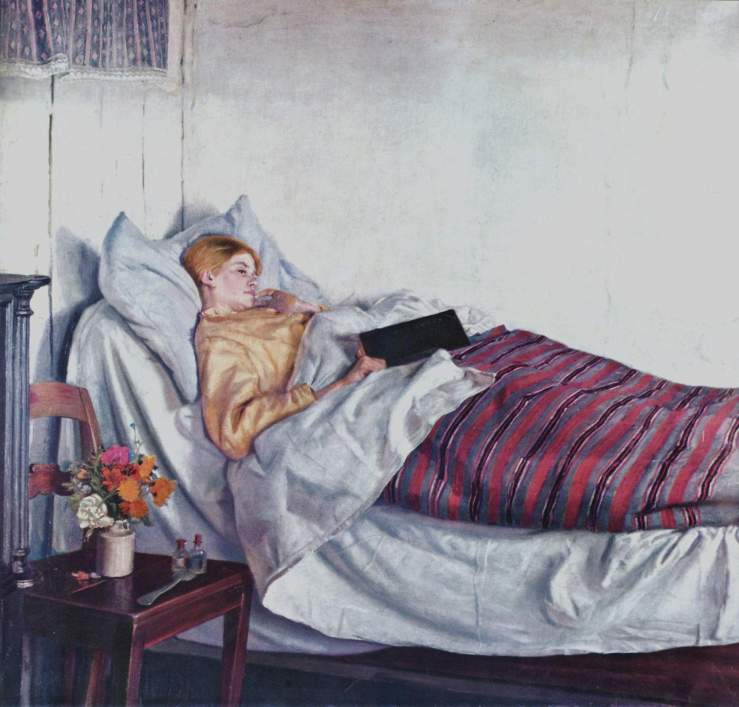

A few years ago, The New York Times ran a little wisp of an article describing the pleasures many readers take in reading “the moldy, dog-eared paperbacks found on the shelves and bedside tables of summer guest rooms.” The article features writers explaining how, staying somewhere, they reach for books they’d normally never pick up, like Wells Tower describing how he ended up reading The Bridges of Madison County. Like most ardent readers, I take a book (or two or three, or, more recently, a Kindle loaded with hundreds) with me anywhere I’m going to stay a night—but I’ll invariably read something I find in the room I’m staying if possible.

Sometimes I’ll end up reading something terrible—once, staying at a beachfront condo, I read an entire serialized Annie Oakley novel even though it was awful. Other times a stay prompts me to pick up a book I’d never reach for in my civilian life. For example, in a cabin in the Blue Ridge Mountains a few years ago I read a naturalist field guide for the area, written and published in the 1950s. More often than not, guest room reading leads me to read much faster and stay up reading much longer than I normally would, simply because I’m trying to finish the book before I leave. This is how I read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Memories of My Melancholy Whores in one long sitting (the book was my uncle), and how I ate up John Barth’s novel The End of the Road in friend’s mother’s childhood room—the book was hers, she had lots of cool books, and I wished I could’ve read more.

The other night, staying with some longtime friends, I reached for a brittle yellowed Peanuts collection on the nightstand by my bed. There were a few volumes of prose and poetry there, but Charles M. Schulz’s comics seemed more likely to make it through the haze of half a dozen beers. Plus, I’ve always loved Peanuts. I read the book entire, an arc beginning with the gang heading off to summer camp and ending, more or less, with Snoopy’s failed attempts at writing.

Like many kids, I grew up with Peanuts, reading Schulz’s work in the paper and also in collected volumes that my grandparents would give me (my grandfather was an especially big fan). The comics were often funny—not funny like my favorite at the time, Gary Larson’s The Far Side to be sure—but they were just as often full of melancholy or even despair, a despair that was mediated, but not necessarily assuaged by, the consolations of friendship.

I read as gently as possible, trying (and not always succeeding) to prevent any more pages from falling out of the collection. I mentally bookmarked several panels and a few entire strips to photograph the next day to maybe share on the blog. The next morning it occurred to me that I own almost a half dozen Peanuts collections—but I probably hadn’t picked them up in years. And I suppose this is one of the strange pleasures of guest room reading—that it might reintroduce us to an old favorite—but that seems like too pat a conclusion to me. I’ve found over the years that I’m just as likely to remember an awful book I read at random as a guest—and that for some reason the experience of reading someone else’s books—in a guest room, at a river house, in a cabin, at a hostel—is somehow always heightened. I don’t have a distinct explanation, other than the very obvious and simple one that I usually read in the same few places—a chair in my living room, a couch, my office, the bed, the bath, my back porch—and that reading other people’s texts in unfamiliar places estranges what I think of as reading—and that estrangement is invigorating. And pleasurable.