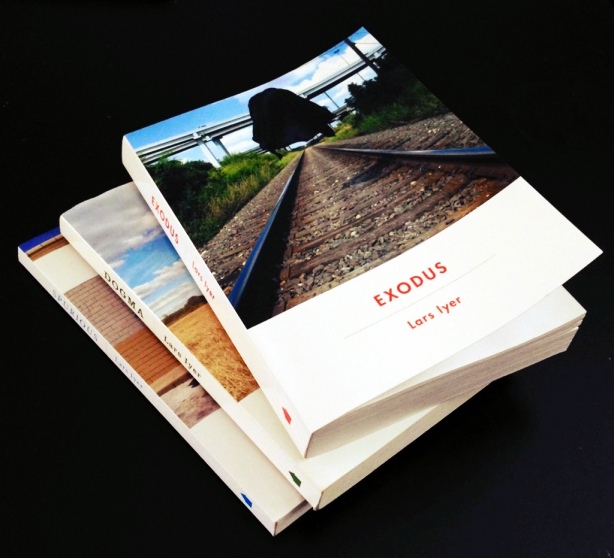

I first interviewed Lars Iyer in 2011, after the publication of his novel Spurious, the beginning of a trilogy that concluded with Exodus (my favorite of the three). I asked Lars to talk with me about his trilogy for an email interview, and we ended up discussing failure, comedy, optimism, academia, American writing, Britain in the mid-eighties, and his forthcoming novel Wittgenstein Jr.

You can get Lars Iyer’s trilogy from publisher Melville House, check out his blog, and find him on Twitter.

Biblioklept: Why a trilogy? Was that by design? Is it a trilogy?

Lars Iyer: Spurious was only a beginning. I wanted to historicise my characters, to present their friendship as part of a larger social, economic and political context. Otherwise, I risked merely contributing belatedly to the literature of the absurd.

Biblioklept: I want to talk about the end of Exodus but that seems like bad form for an interview. Spoilers, etc. Can you comment on where you leave your protagonists, or how you leave them, or why you leave them?

LI: I leave my protagonists roughly where they were at the beginning of the trilogy: rudderless, rather lost, full of a sense of their failure, but with their friendship, such as it is, intact. ‘No hugs, no lessons’: my characters haven’t learned anything…

Biblioklept: Why can’t they learn? Why the repetition? Why not a heroic arc? Why not a saving grace?

Biblioklept: Why can’t they learn? Why the repetition? Why not a heroic arc? Why not a saving grace?

LI: Perhaps because learning implies a kind of resolution that I think is inappropriate for the characters. Kundera says something apposite about Don Quixote. Cervantes makes his would-be knight-errant set off in search of battles, ready to sacrifice his life for a noble cause, ‘but tragedy doesn’t want him’. Kundera goes on:

since its birth, the novel is suspicious of tragedy: of its cult of grandeur; of its theatrical origins; of its blindness to the prose of life. Poor Alonzo Quijada. In the vicinity of his mournful countenance, everything turns into comedy.

So it is with my trilogy. No tragedy! No heroism! No tragic catharsis, that would see the tragic hero being dragged back into line. And no comic catharsis either, in which the older norms of a traditional societal system are reaffirmed. So much comedy is self-congratulatory, self-reassuring: the humour of good cheer, of port and cigars. It shores up things as they are. This is why I can never bear to watch comedy on television. It’s so rare to see comedians turn the joke on themselves. We need cruel comedy. Black comedy, which laughs at itself laughing…

Why the use of repetition in my novels? Because I want to portray the breakdown of things as they are, not once, but again and again. Failure, without amelioration. Serio-comic breakdown, without restitution. Anomie. Helplessness. Crushed hope. How else to acknowledge the prose of our lives?

Much of the humour of Don Quixote, depends on the contrast between lofty ideals and the concrete, everyday, corporeal life. The humour of my trilogy is analogous – but, of course, our everyday is utterly changed! A generalised precarity, un- and under-employment, free-floating anxiety, consumerism, the emphasis on self-representation, the sense that history is over, that politics is all played out, that financial and climatic catastrophe loom…

The tragedy of everyday life is that it’s not even tragic. It never reaches the lofty heights of tragic grandeur. Well, nor do my characters. When W. is at his most wretched, he cannot even die – that’s the end of Dogma. When W. is at his most revolutionary, participating in his own version of the Occupy movement, as at the end of Exodus … well, I won’t spoil the story, but it won’t surprise readers of previous books in the trilogy that there is neither a heroic arc nor a saving grace. Continue reading ““We Need Cruel Comedy” | A Lars Iyer Interview”