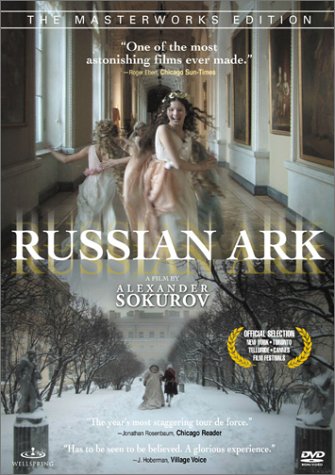

Before I get into the details of Aleksandr Sokurov’s 2002 film Russian Ark, I implore you to stop reading my review and simply get a hold of the film and watch it. It’s a marvelous, rewarding, dreamy experience. That’s not a very convincing argument of course, but I think that the best way to see this gorgeous film is with no preconceptions, with as little information as possible–not because there are plot twists that a review might give away, but rather because the pleasure of Russian Ark is its narrative immediacy–and any review will seek to mediate that immediacy. So I’ve hemmed and hawed. If you need further convincing, read on.

It’s hard to know where to begin, so I’ll let Don DeLillo do it for me. In his latest novella, Point Omega, his filmmaker protagonist describes it as an ideal for the kind of truth he’d like to capture in one of his own films:

There’s a Russian film, feature film, Russian Ark, Aleksandr Sokurov. A single extended shot, about a thousand actors and extras, three orchestras, history, fantasy, crowd scenes, ballroom scenes and then an hour into the movie a waiter drops a napkin, no cut, can’t cut, camera flying down hallways and around corners. Ninety-nine minutes.

That was enough for me to get hold of Russian Ark and watch it, or rather experience it (I think experience is the best verb here, corny as that sounds), but perhaps, gentle reader, you’d like some plot details. Let’s give it a shot. The film begins in darkness, with its unnamed/unseen protagonist describing the vague details of his last memory, a violent accident that he remembers little about. But before we go on, I should point out a few things: this protagonist is unseen because he is essentially the camera; his movement propels the film–is the film–and although he is his own character, he is also a surrogate for the audience. His first-person experience dictates the film, is the film, and although he has ghostly access to the characters who float through the gorgeous halls of the State Hermitage in St. Petersburg, they cannot see or hear him. There is one character who can see him however, an unnamed black-clad 19th-century French aristocrat who the protagonist comes to call “the European.” Neither the European or the protagonist understand why they are in the Hermitage or how they got there; the European is even more perplexed to find that he now speaks perfect Russian. Unlike the protagonist, the European can interact with the denizens of the Hermitage, and interact he does, by turns offending, menacing, or charming (or at least attempting to charm) the characters that the pair encounters as they drift through the ballrooms, galleries, and courtyards of this beautiful palace. Initially, the European repeatedly insults Russian culture, which he believes a pale imitation of European aesthetics. He even protests that one of the fine orchestras that they stumble upon must be manned with Italian players, as Russian musicians simply couldn’t be so skilled. But as they wander the halls, the European slowly succumbs to the rich beauty and opulence of the Hermitage; although he never states it outright, he relents his prejudice against Russian culture, and perhaps even learns a new way of seeing beauty.

And who wouldn’t be moved by the beauty here? Russian Ark functions in some way as a guided tour of the Hermitage, although that term, “guided tour” implies a stuffiness that’s antithetical to the looseness of this film. The camera lingers on a painting or statue; the protagonist offers his thoughts, the European his; perhaps an erstwhile docent steps in to explicate a point of technique or symbolism. It’s wonderful. In one stunning moment (scene would not be the right word for this movie which is of course one long scene), the European argues violently with a boy over a painting of the apostles Peter and Paul. The boy admits to knowing nothing of the scriptures, yet he’s deeply moved by the wisdom and promise that the painting connotes; the European cannot understand how the painting’s aura alone can transmit its meaning to the ignorant lad. The scene begins at 6:38 in the clip below:

The European’s clash with the boy echoes the larger (and yet subtle) clashes of the film, as characters, artworks, and musical styles of different epochs float into or burst out of or parade around in the grand rooms of the Hermitage. There’s Pushkin, Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, Anastasia. There’s an incredible scene where Tsar Nicholas I is offered an apology by the Shah of Iran for the death of an ambassador; there’s a wonderful ballroom dance that moves the European to great joy. In one of the film’s pockets of horror, a layman labors in a strange utility room building his coffin; it is the siege of Leningrad in WWII where over a million people died at the hands of the Nazis. The European, of course, has no knowledge of these events, being after his time, and the disjunction between the protagonist’s contemporary perspective of history and his own provides for a fascinating, if not wholly fleshed out, conflict.

Indeed, one of the greatest pleasures of Russian Ark is its refusal to narrativize or philosophize history beyond a first-person perspective walk through the halls of the Hermitage. The movie erupts into little pockets of exuberant joy or strange, desperate violence; sometimes the protagonist is drawn in, but just as often he’s repelled, and looks for another avenue, like a dreamer willing his own escape. To call the movie dream-like would be an understatement, and like a dream, Russian Ark‘s divergent set pieces overwhelm the senses in their rich splendor. Like the protagonist and the European, I found myself repeatedly entranced by a painting or a concert or a dance or a strange little moment, only to be interrupted by another character intruding into the frame, bearing new information, discordant news that disrupts the dream logic (while paradoxically ushering in a new set piece). Russian Ark distracts its audience, sending them inward; in contemplation, the viewer loses the thread–but is there a thread? Is real life a narrative? Are dreams even narratives? Some of my favorite moments of the film happened when my anxiety at having been distracted by some gorgeous detail was confirmed by the protagonist, who all of a sudden has lost the European, or who is startled by the bustling arrival of new people. But of course, in this film, the viewer is the protagonist.

But writing about Russian Ark is no good, not really. You have to just see it (but I already said that, right?) To quote again from DeLillo’s Point Omega, “The true life is not reducible to words spoken or written, not by anyone, ever.” Sokurov’s film collapses history and art and beauty into a beautiful, edifying, sometimes terrifying dream, a dream that, in its adherence to first-person perspective, is a marvelous approximation of true life. Highly recommended.

First up: Adam Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, a send-up of the publishing industry that sets its targets directly on the current swath of (faked) memoirs that have done gangbusters for publishers in the past few years. Ian Minot is a broke-assed barista one fuck-up away from an overdue firing, who moves from the Midwest to make it as a writer in the big city. Only he’s not doing so well–in contrast to his gorgeous Romanian girlfriend Anya whose literary star is on the rise. For Minot though, this isn’t the worst–that would be the rampant success of über-poseur Blade Markham, a wanna-be gangsta whose memoir Blade on Blade is a blatant fabrication (albeit a fabrication that no one but savvy schlemiel Minot seems to notice (or, at the least, be bothered by)). I read the first fifty-odd pages of the Thieves in one sitting–a good sign to be sure. Langer’s Minot’s voice is familiar territory, the boy who loves to mock the literati he would love to be a part of. In one of the signal moves of his patois, the names of famous authors (and characters) regularly replace common nouns–a bed becomes a proust, a full head of hair is a chabon, sex is chinaski and so on. Minot seems to be headed to running his own grift soon with the help of a man he appropriately calls the Confident Man–should be good stuff. Full review forthcoming. The Thieves of Manhattan is available July 13, 2010 from

First up: Adam Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, a send-up of the publishing industry that sets its targets directly on the current swath of (faked) memoirs that have done gangbusters for publishers in the past few years. Ian Minot is a broke-assed barista one fuck-up away from an overdue firing, who moves from the Midwest to make it as a writer in the big city. Only he’s not doing so well–in contrast to his gorgeous Romanian girlfriend Anya whose literary star is on the rise. For Minot though, this isn’t the worst–that would be the rampant success of über-poseur Blade Markham, a wanna-be gangsta whose memoir Blade on Blade is a blatant fabrication (albeit a fabrication that no one but savvy schlemiel Minot seems to notice (or, at the least, be bothered by)). I read the first fifty-odd pages of the Thieves in one sitting–a good sign to be sure. Langer’s Minot’s voice is familiar territory, the boy who loves to mock the literati he would love to be a part of. In one of the signal moves of his patois, the names of famous authors (and characters) regularly replace common nouns–a bed becomes a proust, a full head of hair is a chabon, sex is chinaski and so on. Minot seems to be headed to running his own grift soon with the help of a man he appropriately calls the Confident Man–should be good stuff. Full review forthcoming. The Thieves of Manhattan is available July 13, 2010 from  I’ve also been reading William H. Gass’s first novel, Omensetter’s Luck. It’s weird, wonderful, Faulknerish in its loose (but somehow layered and constructed) stream of consciousness. Omensetter’s Luck comprises three sections, each progressively longer; I finished the second one today, and so far the novel seems to dance around a description or accounting of its namesake, Brackett Omensetter who carts his family into the small sleepy town of Gilean, Ohio, and immediately perplexes the townsfolk with his amazing luck. As Frederic Morton put it in his contemporary

I’ve also been reading William H. Gass’s first novel, Omensetter’s Luck. It’s weird, wonderful, Faulknerish in its loose (but somehow layered and constructed) stream of consciousness. Omensetter’s Luck comprises three sections, each progressively longer; I finished the second one today, and so far the novel seems to dance around a description or accounting of its namesake, Brackett Omensetter who carts his family into the small sleepy town of Gilean, Ohio, and immediately perplexes the townsfolk with his amazing luck. As Frederic Morton put it in his contemporary  Speaking of Wallace and début novels,

Speaking of Wallace and début novels,  And, speaking of Wallace (again), or at least using him as a crutch–I’ve almost finished Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead by Frank Meeink (“as told to” Jody M. Roy; they’ve sort of got the whole Malcolm X/Alex Haley thing going on there). So, yeah, why the Wallace segue? How to justify it? Well, reading Meeink’s story, the true story of an abused, battered Philadelphia kid who falls into the American neo-Nazi movement and its attendant violent crime and terrorism, who goes to prison and finds redemption and human connection and a new purpose for the nihilistic void of his life, who falls into alcoholism and drug addiction only to be redeemed again–reading Meeink’s story, even knowing its veracity (demonstrable to a point that would satisfy even Langer’s Ian Minot)–I couldn’t help but read his strong, immediate, gritty, and utterly real voice as something not unlike one of the creations in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It’s not just Meeink’s hideousness, his violence, or the grace that he works toward–all constituents of DFW’s collection–it’s that voice, the realness of the volume, surely the book’s greatest asset. Recovering Skinhead is an engrossing read, fascinating in the same way that an infected wound prompts our attention, our paradoxical compulsion and repulsion, but most of all it’s an exhilarating and exhausting performance of voice, of Meeink’s unrelenting, authentic telling of a tale, a telling that any novelist would thrill to channel. Only Meeink’s voice isn’t a novel creation: it’s real. Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead is available now from

And, speaking of Wallace (again), or at least using him as a crutch–I’ve almost finished Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead by Frank Meeink (“as told to” Jody M. Roy; they’ve sort of got the whole Malcolm X/Alex Haley thing going on there). So, yeah, why the Wallace segue? How to justify it? Well, reading Meeink’s story, the true story of an abused, battered Philadelphia kid who falls into the American neo-Nazi movement and its attendant violent crime and terrorism, who goes to prison and finds redemption and human connection and a new purpose for the nihilistic void of his life, who falls into alcoholism and drug addiction only to be redeemed again–reading Meeink’s story, even knowing its veracity (demonstrable to a point that would satisfy even Langer’s Ian Minot)–I couldn’t help but read his strong, immediate, gritty, and utterly real voice as something not unlike one of the creations in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It’s not just Meeink’s hideousness, his violence, or the grace that he works toward–all constituents of DFW’s collection–it’s that voice, the realness of the volume, surely the book’s greatest asset. Recovering Skinhead is an engrossing read, fascinating in the same way that an infected wound prompts our attention, our paradoxical compulsion and repulsion, but most of all it’s an exhilarating and exhausting performance of voice, of Meeink’s unrelenting, authentic telling of a tale, a telling that any novelist would thrill to channel. Only Meeink’s voice isn’t a novel creation: it’s real. Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead is available now from

New York’s WBAI

New York’s WBAI In This Is Where We Live, Janelle Brown’s follow-up to her 2008 début All We Ever Wanted Was Everything, an artsy newly wed couple find their dreams and their marriage unraveling when the payments on their adjustable rate mortgage suddenly double. Claudia and Jeremy are happy at the novel’s outset, living comfortably in their Los Angeles bungalow. Her film Spare Parts garners a huge buzz at Sundance and he reforms a new band after the breakup of his old group The Invisible Spot; they envision their new neighborhood as a contemporary counterpart to the Laurel Canyon creative scene of the 1960s. But then their ARM adjusts and Spare Parts flops. Claudia has to take a job teaching (Gasp! Oh, the terror! In a particularly funny scene, she shows The Graduate to her film students and one of them raises her hand to declare that her father was one of the film’s executive producers). The couple soon has to take in a roommate. Complicating matters even more is the return of Aoki, Jeremy’s unstable–and now famous–ex-girlfriend, who manipulates him every chance she gets. Aoki, a cartoonishly unhinged avant-gardiste, serves as a foil to the more grounded figure of Claudia; as Claudia begins to mature into a more pragmatic, adult personality, Aoki’s siren song calls Jeremy to return to chaos. This Is Where We Live is timely, of course, and Brown takes pains to show how these two “creatives” could overlook such meaningful financial details when looking to buy a home. Some will find Brown’s sympathetic vision of the privileged L.A. art scene off-putting or even shallow, but the novel’s core exploration of a troubled young marriage will resonate with many readers. This Is Where We Live is available in hardback from

In This Is Where We Live, Janelle Brown’s follow-up to her 2008 début All We Ever Wanted Was Everything, an artsy newly wed couple find their dreams and their marriage unraveling when the payments on their adjustable rate mortgage suddenly double. Claudia and Jeremy are happy at the novel’s outset, living comfortably in their Los Angeles bungalow. Her film Spare Parts garners a huge buzz at Sundance and he reforms a new band after the breakup of his old group The Invisible Spot; they envision their new neighborhood as a contemporary counterpart to the Laurel Canyon creative scene of the 1960s. But then their ARM adjusts and Spare Parts flops. Claudia has to take a job teaching (Gasp! Oh, the terror! In a particularly funny scene, she shows The Graduate to her film students and one of them raises her hand to declare that her father was one of the film’s executive producers). The couple soon has to take in a roommate. Complicating matters even more is the return of Aoki, Jeremy’s unstable–and now famous–ex-girlfriend, who manipulates him every chance she gets. Aoki, a cartoonishly unhinged avant-gardiste, serves as a foil to the more grounded figure of Claudia; as Claudia begins to mature into a more pragmatic, adult personality, Aoki’s siren song calls Jeremy to return to chaos. This Is Where We Live is timely, of course, and Brown takes pains to show how these two “creatives” could overlook such meaningful financial details when looking to buy a home. Some will find Brown’s sympathetic vision of the privileged L.A. art scene off-putting or even shallow, but the novel’s core exploration of a troubled young marriage will resonate with many readers. This Is Where We Live is available in hardback from  Little Green, Loretta Stinson’s début novel, tells the story of Janie, an orphan who runs away from her stepmother. Life on the road is tough, and Janie has to make money somehow, dancing in strip bars and even bartering for sex when necessary. When she meets a charmer named Paul who is ten years older than her, she feels instantly closer to him–and naturally hits the road again. Hitchhiking is never a good idea though, kids, especially in a loner’s van, and Janie is brutally beaten. She finds herself under the care of the man who owns the last bar she danced at, and in time, under the care of Paul, reiterating one of the novel’s major themes of cyclical violence and female dependence on a man. Paul is a small-time drug dealer whose habits extend beyond weed and acid into heroin and meth. As his drug addiction spirals, he tries to find some control by manipulating Janie; in time, he beats her so terribly that she has to go to the hospital. Janie leaves him but he stalks her wherever she goes, forcing her to find her own strength and self-reliance as the novel reaches its redemptive climax. Paul is probably the most interesting character in Little Green, and although it would be unfair to call Janie a flat character, she spends much of the novel as a victim. In contrast, Paul’s addiction and behaviors are studied with a psychological depth that attempts to understand–without ever rationalizing–his actions. While the novel is hardly sympathetic to him, Stinson resists painting Paul as a static monster; the payoff is a villain far-more frightening because of his authenticity. Authenticity is what keeps Little Green (for the most part) from verging into melodramatic Lifetime movie of the week territory. Stinson’s finely detailed evocation of the Pacific Northwest

Little Green, Loretta Stinson’s début novel, tells the story of Janie, an orphan who runs away from her stepmother. Life on the road is tough, and Janie has to make money somehow, dancing in strip bars and even bartering for sex when necessary. When she meets a charmer named Paul who is ten years older than her, she feels instantly closer to him–and naturally hits the road again. Hitchhiking is never a good idea though, kids, especially in a loner’s van, and Janie is brutally beaten. She finds herself under the care of the man who owns the last bar she danced at, and in time, under the care of Paul, reiterating one of the novel’s major themes of cyclical violence and female dependence on a man. Paul is a small-time drug dealer whose habits extend beyond weed and acid into heroin and meth. As his drug addiction spirals, he tries to find some control by manipulating Janie; in time, he beats her so terribly that she has to go to the hospital. Janie leaves him but he stalks her wherever she goes, forcing her to find her own strength and self-reliance as the novel reaches its redemptive climax. Paul is probably the most interesting character in Little Green, and although it would be unfair to call Janie a flat character, she spends much of the novel as a victim. In contrast, Paul’s addiction and behaviors are studied with a psychological depth that attempts to understand–without ever rationalizing–his actions. While the novel is hardly sympathetic to him, Stinson resists painting Paul as a static monster; the payoff is a villain far-more frightening because of his authenticity. Authenticity is what keeps Little Green (for the most part) from verging into melodramatic Lifetime movie of the week territory. Stinson’s finely detailed evocation of the Pacific Northwest  of the late 1970s explores how attitudes about gender roles, women’s rights, and drugs came to a seething breaking point a decade after the summer of love. Significantly (and sadly), the novel’s depiction of domestic violence reads with a wholly contemporary immediacy. Little Green is new in handsome trade paperback this month from

of the late 1970s explores how attitudes about gender roles, women’s rights, and drugs came to a seething breaking point a decade after the summer of love. Significantly (and sadly), the novel’s depiction of domestic violence reads with a wholly contemporary immediacy. Little Green is new in handsome trade paperback this month from