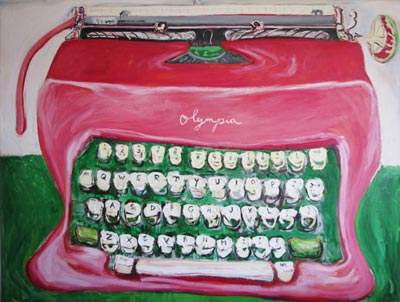

This month, the good folks at Picador are issuing an expanded edition of Paul Auster’s essays, memoirs, prefaces, true stories, anecdotes, and interviews. Inconspicuously titled Collected Prose and running to just under six hundred pages, the volume includes Auster’s début work The Invention of Solitude in its entirety. Solitude is a strange blend of personal memoir, an account of the young writer’s reaction to and relationship with the death (and life) of his father, as well as a philosophical meditation on the absurdity of family, art, and time. Collected Prose also includes the later memoir, Hand to Mouth, a reflective piece on Auster’s early failures as he tries to make it as a writer, including his time in Paris, his marriage to Lydia Davis, his hunger, and his poverty. While Solitude inaugurates many of the experimental structures and postmodern tropes that Auster would be identified with throughout his career as a novelist, the flatter, more direct style of Hand to Mouth is more indicative of the tone of much of Collected Prose. There’s a journalistic directness and keen earnestness to Auster’s essays that perhaps belie his postmodern bona fides. That’s a good thing, allowing Auster to communicate directly about his sometimes challenging subjects to a wider audience. Style aside, both of the book-length memoirs at the front end of Collected Prose neatly delineate the themes that preoccupy much of the rest of the book: art, language, writing, writers, poverty, absurdity, movement, New York City, and so on. And although the book turns away from Auster’s memoirs and true stories in its second half, presenting his essays, editorials, and prefaces, there’s still a sharp sense of Auster in each essay. These are personal essays. Auster writes about his friend Philippe Petite, the French high-wire artist; he writes about the literal hunger artists face, using Knut Hamsun and Franz Kafka as examples; he writes a vindication for Dada daddy Hugo Ball; he writes on over half a dozen relatively obscure poets to let us know why they matter. There are wonderful little moments, like “The Story of My Typewriter,” where Auster exclaims his love for his quiet Olympia (he buys 50 typewriter ribbons fearing the specie’s eventual extinction). The book reprints the Sam Messner paintings that originally accompanied Auster’s text (or, perhaps, vice versa).

Another great moment is the essay “Hawthorne at Home,” which takes a look at a little known piece by Nathaniel Hawthorne called Twenty Days with Julian & Little Bunny. Hawthorne’s piece is more or less a straightforward narrative account of Hawthorne alone with his five-year old son Julian and his pet rabbit for three weeks while wife Sophia visited the Peabodys. While Auster gives the reader a lesson on Hawthorne and his composition of The Scarlet Letter here, the essay focuses on the idyllic charm of a father and son, a rare subject in Hawthorne’s oeuvre. As a bonus, Herman Melville makes a cameo. “Hawthorne at Home” is the sort of essay that makes you want to go read the source material; it sent me hunting for a used copy of American Notebooks.

As one might imagine, Collected Prose is absolutely larded with writers, and lovingly so. Auster does not suffer from the inclination toward meanness that so many critics feel toward their peers, perhaps because he writes foremost from the perspective of an artist. Not that it’s difficult to praise Art Spiegelman (“The Art of Worry”) or pray for Salman Rushdie (um, “A Prayer for Salman Rushdie”) or speak to the genius of Samuel Beckett (“Remembering Beckett on His One Hundredth Birthday”) and Jim Jarmusch (“Night on Earth: New York”)–but Auster illuminates their work in a way that transcends the postmodern concerns of technique, place, and politics, and speaks directly to a certain aesthetic excellence. His love for storytellers extends beyond the pros, of course, evinced in his work with NPR’s National Story Project. He credits wife Siri with coming up with the idea of having NPR listeners write and submit their own original stories, but his enthusiasm for her idea resonates in his warm preface to the eventual book that collected the listeners’ submissions. Auster writes, “I learned that I am not alone in my belief that the more we understand of the world, the more elusive and confounding that world becomes.” The world becomes more “confounding” after the 9/11 attacks, of course, and like so many other writers Auster attempted to somehow measure the tragedy in words. “Random Notes–September 11, 2001–4:00 PM” is a scrap, a fragment, a shell-shocked missive that ends with the haunting words “And so the twenty-first century finally begins.”

It might be misleading to call Collected Prose a good introduction to Paul Auster’s nonfiction–can a work so comprehensive, so massive be a mere starting point?–but it is a great introduction, so there. It’s also a fantastic overview of critical, literary, and artistic theory, written from a deeply personal perspective. Let’s hope that fifteen years from now we’ll have another expanded edition of Auster’s prose; in the meantime, we can look forward to his new novel Sunset Park this November. Highly recommended.

[…] after being away for a week. I had mixed feelings about Auster’s last novel Sunset Park, but I dig his nonfiction, and I opened Winter Journal randomly to an episode where the adolescent Auster loses his […]

LikeLike

Way cool. Love it!

LikeLike