In a 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy famously said that he only cares for writers who “deal with issues of life and death.” He disses Proust and Henry James, saying “I don’t understand them . . . that’s not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange.” Because he has granted so few interviews–and come off so guarded in those he has done–McCarthy’s dictum on “good writers” has perhaps become a bit inflated, elevated from one man’s opinion to a grand litmus test of literary worth. Still, I often find myself putting the books I read under the McCarthy stress-test: do they narrativize the Darwinian drama of life and death? Or are they simply bloodless spectacles of rhetoric, ephemeral social critiques, or faddish forays into solipsism? McCarthy’s targets, Proust and James, arguably do address life and death issues in their works, but when compared to McCarthy’s heroes–Melville, Faulkner, Dostoevsky–the social fictions of Proust and James seem wan, or at least too subtle and overly-coded. The two novels I’m currently working through, Jonathan Lethem’s Chronic City and Hans Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone, illustrate not just the poles of McCarthy’s dichotomy, but also why many readers (myself included) tend to prefer that their novels address matters of life and death.

Every Man Dies Alone, first published in German in 1947, is available for the first time ever in English, thanks to translator Michael Hoffman (if you’ve read Kafka in English, you’ve probably read Hoffman’s work) and the good folks at Melville House. Fallada’s novel tells the story of German resistance to the Nazi regime, not at an aristocratic or militaristic level (this isn’t Valkyrie), or even a literary or philosophical level, but at the level of every day, ordinary existence. After the death of their son in battle, Otto and Anna Quangel initiate a campaign of resistance to the Nazi party, one that is of course doomed from the outset. The Quangels soon involve Eva Kluge, among others, in their covert resistance cell. Kluge is a letter-carrier who becomes disgusted with the moral implications of the regime; she’s also deeply embittered by the way Nazi rule has systemically destroyed her family. Kluge’s peripatetic job helps to enact Fallada’s major rhetorical gesture, a sweeping busyness that vividly recreates the life of ordinary Germans during the rule of the Third Reich. We might begin in Kluge’s mind as she embarks to deliver a letter, only to find ourselves awash in the thoughts of its recipient a few pages later. Fallada’s omniscient third-person narrator moves freely from one character’s consciousness to another’s, shifting fluidly from the immediacy of present tense to the solidity of past tense. It’s modernism (whatever that means)–Tolstoy without the rich and famous, Joyce without the mythos and erudition, but deeply engaging in its scope. WWII has produced a seemingly endless myriad of narratives, yet Fallada’s tome is the first that I’ve experienced of its kind. Perhaps its subject matter–the lives of ordinary Germans and their unsuccessful attempts to resist the mundane evil all around them–is simply not the stuff that we want from our war stories, and perhaps this is why the book has been absent so long from an English translation. It’s evocative of a world that I had never really considered before: after all, the narrative of WWII is far easier to comprehend if you retain the simplicity of the good guys (the Allies), the bad guys (the Nazis), and the victims (the Jewish population of Europe). Ordinary Germans have only one place in this uncomplicated system, which is why the story of the Quangels and their cohort is so profound (oh, the Quangels are based on the real-life Nazi resisters Otto and Elise Hampel, if you must know). Driven in part by despair, they seek to forge meaning in their lives, even if its at the cost of death, or the horrors of a concentration camp. To return to McCarthy’s caveat, Fallada’s novel is a work that dramatizes life and death against a decidedly unheroic backdrop, a novel that makes its reader repeatedly ask himself whether or not he would be, to use another McCarthyism (from The Road) one of the “good guys.” Great stuff, and so far one of the better novels we’ve read this year. Go get it.

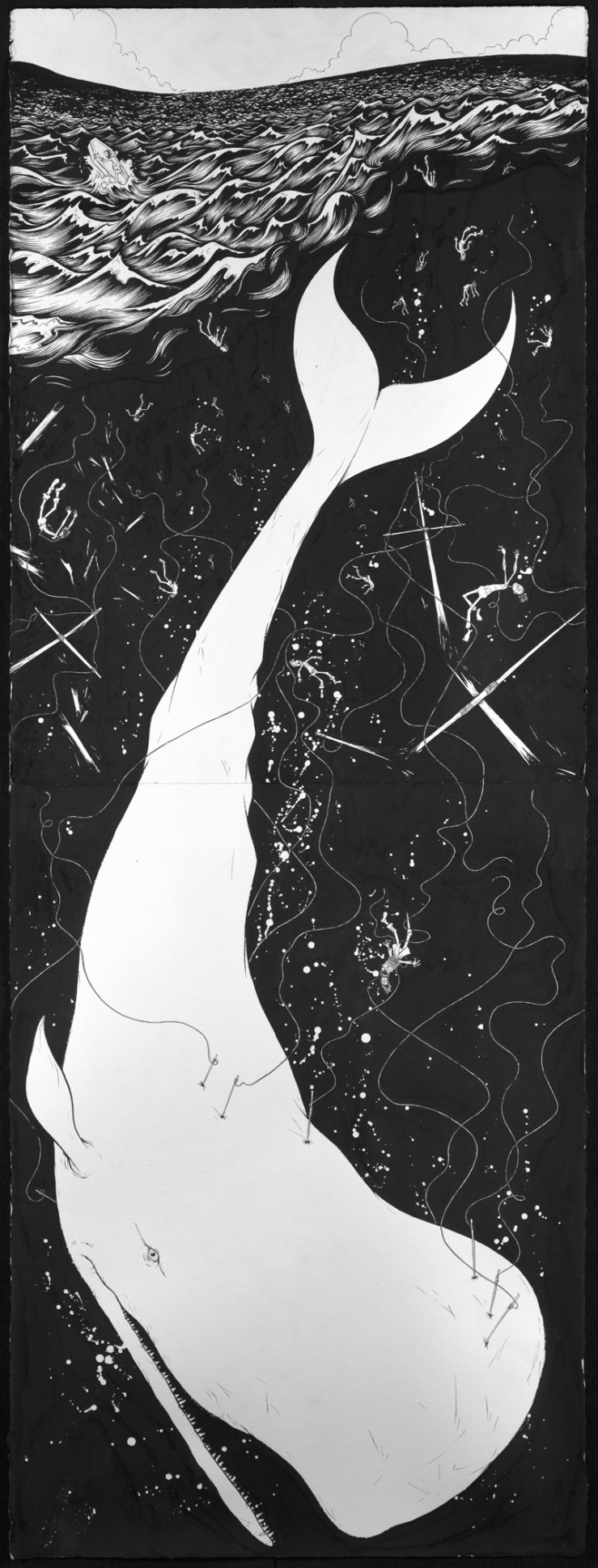

It’s perhaps unfair to lump Lethem’s latest in a review with Fallada, given the historical complexity of Every Man Dies Alone‘s milieu. Still, I’ve been reading my review copies of both novels over this long weekend, trying to catch up, and I find that I would almost always rather pick up Fallada’s book. It compels me, whereas, half way through Chronic City, I still find nothing to care about, no risk, no cost, no guts. No matters of life and death. The novel centers around former-child actor Chase Insteadman, whose directionless existence seems to thematically underpin the book. Chase moves from party to party in a fictitious Manhattan, charming various socialites and keeping boredom (marginally) at bay. He soon hooks up with Perkus Tooth, a marijuana-addicted pop culture critic, whose characteristics will be familiar to pretty much anyone who earned a liberal arts degree in college. Tooth seems to function largely as a mouthpiece for Lethem to espouse various opinions on movies and books and art. It’s a clumsy device as it doesn’t shade the character–it’s simply Lethem couching his cultural criticism in the comfort of a work of fiction. In a particularly telling scene, Perkus picks up a copy of The New York Times and thinks that it feels too light. He looks up at the right-hand corner: “WAR FREE EDITION. Ah yes, he’d heard about this. You could opt out now.” Perkus seems to deliver the line as a criticism, but it’s Lethem who’s opting out. He drops hints of destruction and annihilation and disintegration in the novel–there’s a giant tiger on the loose somewhere in Manhattan; Chase’s fiancée floats estranged in space, stranded on the International Space Station; a crooked mayor is up to dastardly shenanigans–but Lethem protects his characters from it all in an insulating cocoon of marijuana smoke and pop trivia. Their forays into the darkness of Manhattan’s mysteries are meant to play both humorously but also with enough danger to fully invest a reader’s attention (think of Lethem’s more successful sci-noir Gun, with Occasional Music, or his detective thriller Motherless Brooklyn). Instead, the adventures fall flat, collapsing back into Perkus’s apartment, a vortex of (ultimately meaningless) pop culture. While the novel is by no means terrible–it’s well-written, of course–there is simply a tremendous lack of the “life and death” stuff that McCarthy–and other readers–require. In short–and in contrast with Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone–it does not compel itself to be read. Which is a shame of course. I still think Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude was one of the finest books of the decade, and I was deeply disappointed in his last novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet. Chronic City is a much finer book than that silly train wreck, but it lacks the urgency of Lethem’s finest works, Fortress and Motherless Brooklyn, which temper a love of popular culture with genuine characters and an affecting plot.

I’ll conclude by returning to Cormac McCarthy, this time to his latest interview (in The Wall Street Journal). He says, on writing novels: “Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing.” And later: “Creative work is often driven by pain. It may be that if you don’t have something in the back of your head driving you nuts, you may not do anything.” For McCarthy, literature, in its final product–the reader reading the book–is the direct communication of the pain of creation, the awkward and incomplete translation of ideas exchanged from author to audience. Perhaps the pain was too much for Fallada, who died in 1947 of a morphine overdose, but that pain–that spirit–exists in the book. A similar spirit exists in Lethem’s earlier works; I’d love to see him tap into it again in his next venture.

Every Man Dies Alone is now available in hardback from Melville House.

Chronic City is now available in hardback from Double Day.

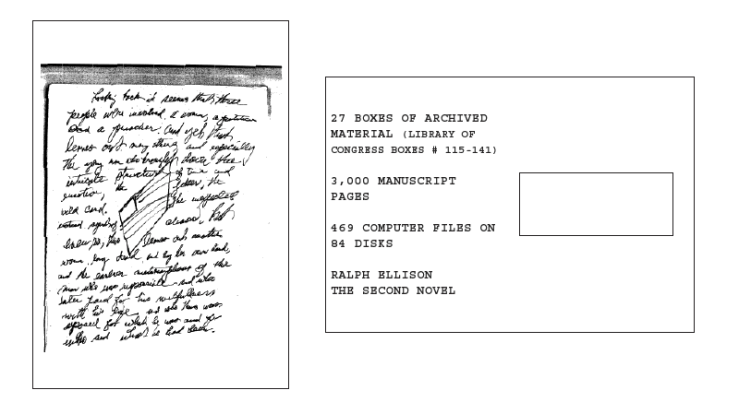

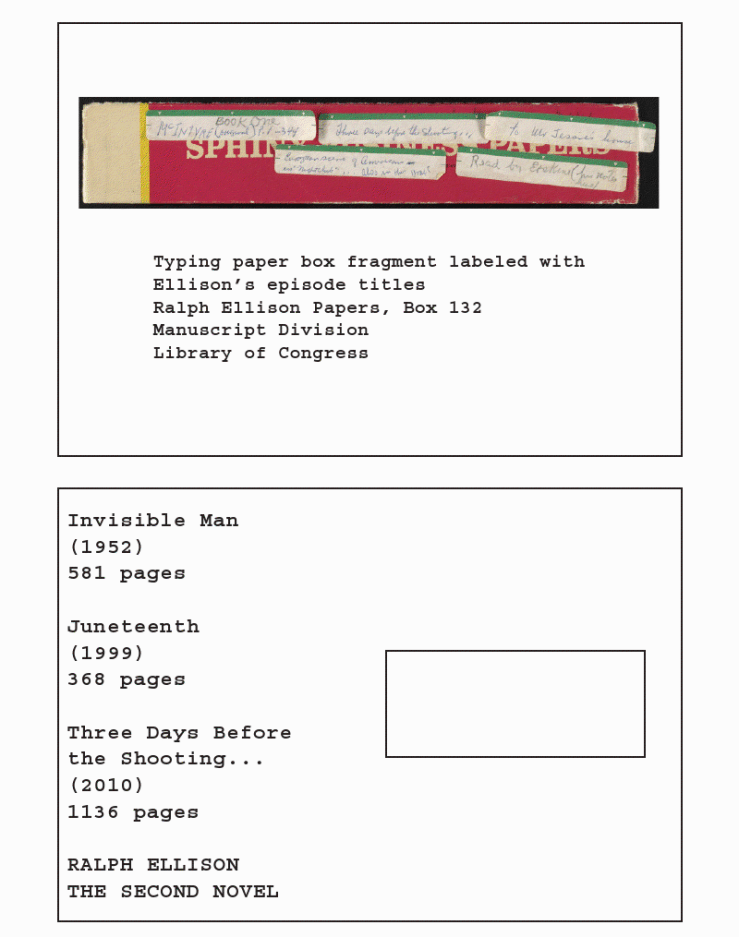

A second novel from Ralph Ellison? Wasn’t that Juneteenth, the posthumous work pieced together from thousands of pages and notes by Ellison’s literary executor, John Callahan? The one that was kinda sorta panned as a mess (or at least an incomplete vision)? A few weeks later, another postcard:

A second novel from Ralph Ellison? Wasn’t that Juneteenth, the posthumous work pieced together from thousands of pages and notes by Ellison’s literary executor, John Callahan? The one that was kinda sorta panned as a mess (or at least an incomplete vision)? A few weeks later, another postcard: So we were still a little confused. Was Three Days Before the Shooting… a more complete version of Juneteenth, or a wholly separate novel? A week or two later, a third postcard showed up with some answers: Ralph Ellison’s Three Days Before the Shooting… is a re-edit of the material originally presented as Juneteenth back in 1999, expanded from 368 pages to 1136 pages. Hopefully, Ellison’s vision will be restored here.

So we were still a little confused. Was Three Days Before the Shooting… a more complete version of Juneteenth, or a wholly separate novel? A week or two later, a third postcard showed up with some answers: Ralph Ellison’s Three Days Before the Shooting… is a re-edit of the material originally presented as Juneteenth back in 1999, expanded from 368 pages to 1136 pages. Hopefully, Ellison’s vision will be restored here.