Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel Snow Crash opens with an extended scene in which the book’s protagonist races to deliver a pizza on time for the mafia. The scene is thrilling and ridiculous, establishing the book’s frenetic, ironic tone and painting a rough outline of Snow Crash’s milieu. Like many sprawling works of speculative fiction, Snow Crash is more interested in rendering its milieu in vibrant, hyperkinetic color than it is concerned with delivering plot and character development. Snow Crash’s plot is the sort of joyfully convoluted careening mess that makes a reviewer (okay, this reviewer) shudder at the thought of having to successfully paraphrase, so I’m not even going to make an earnest effort. Let’s get to that milieu and the cartoon characters who inhabit it.

Snow Crash is set in the early 21st century, primarily in Los Angeles, which is no longer part of the United States. Actually, there isn’t much of a United States to speak of, really—and not even a municipal Los Angeles, per se. Instead, the terrain is totally privatized. Privatized roads, privatized spaces. People (who can afford to) live in franchised burbclaves protected by hired mercenaries or private militias or robots that keep out the undesirables. (The white folks who live in New South Africa want “racial purity,” while some franchise nations, like Mr. Lee’s Greater Hong Kong are open to anyone who can trade information). Authority is for sale. Conditions are so laissez-faire that the Mafia is truly a Legitimate Business now (complete with their own CosaNostra Pizza University). In fact, all business is legitimate; several times in Snow Crash, a character will refer to “the old days when they had laws.” Without regulation, hyperinflation is the norm; the homeless use trillion-dollar bills to light their campfires.

There’s a hard-edged griminess to the world Stephenson conjures in Snow Crash, but the book is never grim or dour, and instead embraces the anarchic-capitalism it proposes. Perhaps this is because Stephenson’s heroes are such radically exceptional people. The book’s hero is named Hiro Protagonist, the kind of Pynchonian goof that characterizes Snow Crash’s zany tone. Hiro meets the book’s other protagonist, a fifteen year old blonde who goes by Y.T. (“Yours Truly,” although most of the folks tend to hear “whitey”). Y.T. is a Kourier, a skateboarding delivery person who harpoons vehicles to catch a free ride. She helps Hiro deliver that pizza in the opening scene and the two team up after Hiro gives her his business card. It reads: “Last of the Freelance Hackers / Greatest swordfighter in the world / Stringer, Central Intelligence Corporation. Specializing in Software related Intel. (Music, Movies & Microcode.)” Did I neglect to mention that Hiro carries two samurai swords with him wherever he goes?

Hiro’s pretty handy with those swords, but his real skill is hacking, and he spends a good deal of time in the Metaverse, a virtual reality-based internet space where avatars go to bars and chat and sell &c. It’s sort of like a mix between Facebook and World of War Craft. In 1992 (earlier, I suppose), Stephenson’s way ahead of the curve. Here, he describes avatars:

Your avatar can look any way you want it to, up to the limitations of your equipment. If you’re ugly, you can make your avatar beautiful. If you’ve just gotten out of bed, your avatar can still be wearing beautiful clothes and professionally applied makeup. You can look like a gorilla or a dragon or a giant talking penis in the Metaverse. Spend five minutes walking down the Street and you will see all of these.

There are plenty of passages like this, where Stephenson pegs some aspect of internet culture ten years before it actually happens. (I couldn’t help but think about Wikipedia during Hiro’s conversations with a program called Librarian). It’s probably fair to say that the Wachowskis lifted as much from Snow Crash as they did from William Gibson’s cyberpunk trilogies.

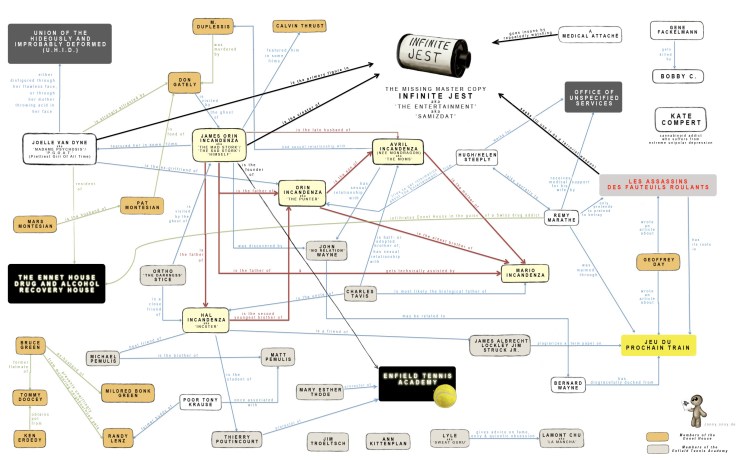

While I’m there, I might as well lazily point out that Snow Crash would fit neatly at home on a shelf with Neuromancer or Mona Lisa Overdrive. There’s also a heavy dose of Philip K. Dick weirdness in Snow Crash, particularly when the book settles into its major metaphysical plot about ancient Sumerian gods and goddesses and linguistic viruses and the Tower of Babel. Stephenson’s Snow Crash is zanier than William Gibson’s dark depictions or Dick’s mindmelted milieux, and it would hardly do to call what he does here light—but there is something joyful, playful about his satire. I invoked Pynchon earlier and I’ll do it again; parts of Snow Crash also reminded me of David Foster Wallace’s opus Infinite Jest. Both IJ and SC obsess over the minutest details of speculative technologies and how people might react to such technologies. This is often what sets Snow Crash heads and shoulders above run of the mill cyberpunk. In just one instance, Stephenson parodies the language of bureaucratic speech at length; Y.T.’s mom, who works for what’s left of the Federal Government, is subjected to a memo about toilet paper usage that goes on for pages. The passage is hilarious, and adds absolutely nothing to the plot development—it simply helps to flesh out the contours of the world that Stephenson has imagined.

All of this detailed imagining unfortunately comes at the expense of a plot that only coheres through massive exposition dumps. About a third of the way into the novel, the major conflict is finally established, but only through a dialog between Hiro and the Librarian that reads almost like a catechism. As the book reaches its climax, Hiro actually explains what’s going on to a few of the other major characters—and the reader, of course. It’s a cringe-worthy moment, the sort of rhetorical weakness that smacks of genre fiction; even worse, the plot’s action ultimately hangs on some fairly basic hoary old tropes that wouldn’t be unfamiliar to anyone who’s ever played a video game. The book lags under a juvenile obsession with weapons and badassery in general. And the book’s resolution . . . well, let’s just say that Stephenson sticks the ending, but it all feels too pat and too slight after the dazzling weight of the world that he’s established. Still, at its finest, Stephenson’s prose is zippy, shining, hilarious stuff, and his employment of multiple character perspectives moves the book with an addictive energy. Snow Crash is beach reading for folks who like some humor with their dystopia.

A film adaptation of Snow Crash is supposedly going into production soon, with British director Joe Cornish taking charge. I liked Cornish’s last film Attack the Block, and Snow Crash clearly has a highly-imagistic, cinematic feel to it—but I think a film is not the way to go. Simply put, Snow Crash is too big, too larded with characters and details (so many that I failed to touch on in this review) to translate well onscreen. I think an eight part miniseries on HBO (or a similar network) would be perfect, even if it came at the expense of special effects—-a miniseries would give the filmmakers time to build Stephenson’s nuanced world. I’m afraid otherwise we’ll get a travesty like the adaptation of The Golden Compass, or something like The Hunger Games film, where all but the most basic plot points are elided. But I suppose a miniseries is not as lucrative as a blockbuster film. I hope the filmmakers at least split the book in two. In any case, I’ll be interested to check out the results.

![pale king 9781926428178[1]](https://biblioklept.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/pale-king-97819264281781.jpg?w=739&h=1094)

I’m not sure what Ellis’s tweet meant, and attendees of the Hackney reading claim that he was more considered and measured in his tone than the actual words of his response seem to entail. His end of the agon with Wallace is also rife with its own set of problems—his contemporary is dead, horribly dead, a suicide, (the kind of death that makes an essay like this one, an essay that claims to find affirmation of life in DFW and empty nihilism BEE, particularly hard to swallow, I suppose)—making it all the harder to respond. I read his “too soon” remark from the Hackney reading to be in earnest.

I’m not sure what Ellis’s tweet meant, and attendees of the Hackney reading claim that he was more considered and measured in his tone than the actual words of his response seem to entail. His end of the agon with Wallace is also rife with its own set of problems—his contemporary is dead, horribly dead, a suicide, (the kind of death that makes an essay like this one, an essay that claims to find affirmation of life in DFW and empty nihilism BEE, particularly hard to swallow, I suppose)—making it all the harder to respond. I read his “too soon” remark from the Hackney reading to be in earnest.