Camelia Elias is the founder and editor-in-chief of EyeCorner Press, an independent publisher devoted to printing a host of difficult-to-classify writings, including creative academic writing, and poetic fragments and aphorisms. EyeCorner publishes works in English, Danish, and Romanian, as well as bilingual editions. This multilingual approach gels with the publishing house’s fragmentary philosophy, as well as its origins as a collaborative venture between universities in three nations. In addition to her editorial duties, Elias is also one of EyeCorner’s authors; her latest work Pulverizing Portraits is a monograph on the poetry of Lynn Emanuel. Elias is Associate Professor of American Studies at Roskilde University in Denmark and she blogs at FRAG/MENTS. Elias was kind enough to talk with me over a series of emails; in our discussion she defines creative criticism, discusses the value in being open to error, accounts for hostility against deconstruction and post-structuralism in academia, and explains why it doesn’t hurt to throw the word “fuck” into a textbook now and then.

Biblioklept: EyeCorner Press is somewhat unusual, even for an indie publisher — a joint venture between universities in Denmark, Finland, and the US that focuses on creative criticism. How did the press come into being?

Camelia Elias: The press came into being as an act of anarchism, if you like, a form of resistance against the idea that academic work must be measured not only against its own standard, but also against the standard that idiotic governments sets for measuring, and hence controlling, intelligence, creativity, and freedom. In 2007 I was editing new research papers written by colleagues and associates of the Institute of Language and Culture at Aalborg University with view to publication by the Faculty of Humanities at AU. A new change in leadership also brought about a new set of ideas. These were rigidly formulated along the newly established injunction passed down by the Danish government, which dictated that all Danish academics must now prioritize publishing with Oxford and Harvard. Without getting into the silly and imbecilic arguments produced for the sustainability of such a demand in reality, the fact remains that many heads of department throughout our Danish universities tried to implement the new regulations literally. The good publishing folks at Aalborg were told that Research News (the publishing venue) was going to close, and no, as the justification for it ran, this was not because the papers were not good enough, but 1) because publishing new research under the aegis of the department was likely to have the undesirable effect of preventing the researchers from expanding their range of publishing possibilities – and hence not consider Oxford and Harvard – and 2) there will be no money for it anymore. Few of us tried to make obvious the stupidity pertaining to the first argument – bad idea, as bosses generally don’t want to be told that they have limited visions – and as to the second argument, pertaining to the precarious, or rather by then non-existent financial support, a few of us also tried to suggest that we could go ‘on demand’ and even work ‘con amore’ for it, which would involve no expenses. The answer was still no. So, there we were, with a few manuscripts in the pipeline and no possibility of getting them out. As the editor of these papers, I felt a responsibility not only towards the writers but also towards the readers who had bothered to peer-review the works. I decided to start EyeCorner Press in my own name, but retain the ties we had in terms of publishing jointly with a few other partner universities. With Brenau University in Gainesville, Georgia, we had just finalized a volume on transatlantic relations (aesthetics and politics) within Cultural Text Studies Series published by Aalborg University Press. We are happy to call them our close allies. University of Georgia, Gwinnett, and Oulu University in Finland followed suit and so did Roskilde University, which became my new working place not long after the Aalborg ‘situation’.

Continue reading “Biblioklept Interviews Camelia Elias, Editor-in-Chief of EyeCorner Press”

In W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity, J.J. Long posits that the work of the late German author W.G. Sebald is best understood as the struggle for autonomous subjectivity in a world conditioned by the power structures of modernity. If the term “power structures” wasn’t a big enough tip-off, yes, Long’s analysis of Sebald is largely Foucauldian, and although he cites Foucault more than any other theorist (Freud is a distant second), the book is not a dogged attempt to make Sebald’s prose stick to Foucault’s theories. Rather, Long uses Foucault’s techniques to better understand Sebald’s works. As such, Long examines the ways that modernity affects power on the human body in Sebald’s work, tracing his protagonists’ encounters with modern institutions that exert power via archive and image.

In W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity, J.J. Long posits that the work of the late German author W.G. Sebald is best understood as the struggle for autonomous subjectivity in a world conditioned by the power structures of modernity. If the term “power structures” wasn’t a big enough tip-off, yes, Long’s analysis of Sebald is largely Foucauldian, and although he cites Foucault more than any other theorist (Freud is a distant second), the book is not a dogged attempt to make Sebald’s prose stick to Foucault’s theories. Rather, Long uses Foucault’s techniques to better understand Sebald’s works. As such, Long examines the ways that modernity affects power on the human body in Sebald’s work, tracing his protagonists’ encounters with modern institutions that exert power via archive and image. Long’s study of Sebald is very much a description of modernity; in particular, of modernity as a series of affects of power and discipline upon the subject (again, very Foucauldian). It’s not particularly surprising then that Long, after locating so many Sebaldian traumas in the 19th and early 20th centuries, asserts that Sebald is a modernist and not a postmodernist. He bases this claim not on the formal elements of Sebald’s prose, which he readily concedes can just as easily be read as postmodernist, but rather on the way his “texts respond to the specific historical constellation” of modernity. Long continues–

Long’s study of Sebald is very much a description of modernity; in particular, of modernity as a series of affects of power and discipline upon the subject (again, very Foucauldian). It’s not particularly surprising then that Long, after locating so many Sebaldian traumas in the 19th and early 20th centuries, asserts that Sebald is a modernist and not a postmodernist. He bases this claim not on the formal elements of Sebald’s prose, which he readily concedes can just as easily be read as postmodernist, but rather on the way his “texts respond to the specific historical constellation” of modernity. Long continues– Time

Time  In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from

In their introduction to J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, editors Anton Lesit and Peter Singer make the claim that the essays in the new collection “show the folly of Plato’s idea that literature has nothing to contribute to philosophical discussion. Instead they are an invitation to a dialogue that can sharpen the issues that literature raises while making philosophy more imaginative.” Lesit and Singer briefly review the philosophical tradition, from the time of Plato’s call to banish the poets to the current wars between pragmatists and postmodernists, specifically foregrounding the case for Coetzee’s literature as a legitimate source of philosophical inquiry. They identify three specific features of his works — reflectivity, truth seeking, and an exploration of social ethics — that merit critical attention. The essays in the volume address “the psychological and moral phenomenology of personal relationships; the consequences of human suffering, evildoing, and death for human rationality and reason; and the literary methods invoked to open areas of experience beyond the abstract language of philosophers.” The editors also point out that “Unsurprisingly, the ethics of animals looms large in this collection,” a concern that might attract animal ethicists and others interested in animal-human relationships who might not immediately turn to literature for answers (or questions). On the whole, J.M. Coetzee and Ethics, while obviously a specialty volume, strives to appeal to a wider audience, eschewing much of the acadamese that plagues (and obfuscates the arguments of) so many critical volumes. Fans of Coetzee will wish to take note. J.M. Coetzee and Ethics is new in hardback from

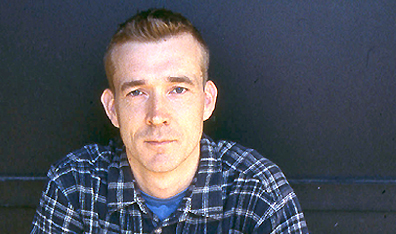

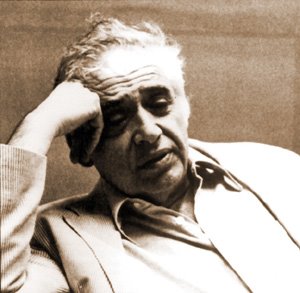

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says– As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two– This weekend, I read and thoroughly enjoyed the first volume of Adam Thirlwell’s The Delighted States (new in a handsome trade paperback edition from

This weekend, I read and thoroughly enjoyed the first volume of Adam Thirlwell’s The Delighted States (new in a handsome trade paperback edition from