In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In truth, Bloom’s word invention is an enthusiastic Wildean necessary exaggeration. It is Bloom’s way of registering our almost religious sense that we live in Shakespeare’s shadow and that he does not simply represent human beings but brings new life, more life, into the world. . . . Bloom’s determination to honor Shakespeare’s godly primacy is a kind of secular theology.

The second section of Wood’s essay should be required reading for all English majors (or anyone serious about literary criticism). Here, Wood provides a wonderfully succinct overview of the history of literary criticism, connecting Freudian analysis and the New Critics to the various theories that Bloom would come to call the “The School of Resentment.”  As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

This is a long way around to Bloom, but it may explain the venom and desperation of his attacks. For although deconstruction did not intend to, it has produced mutant modes of reading that, when combined with leftish political guilt or ressentiment, seem to threaten the existence of literature as a discipline.

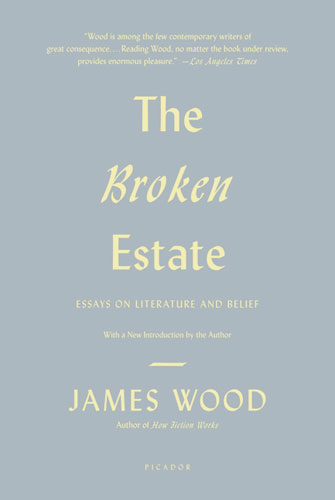

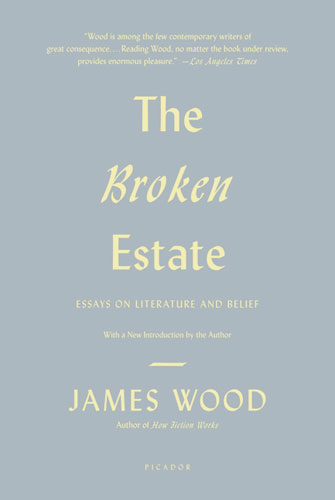

Wood espouses some common sense here uncommon in literary criticism, taking a long view that recognizes–and attempts to step outside of–the fact that it’s not all academic when it comes to how we read our books. History and politics matter, but so does our passion, our love for our books (as silly as that may sound). He defends Bloom’s work even as he calls it an overreaction. He credits deconstruction as having “produced some brilliance and many distinguished readings (no one could deny the acuities of Derrida, of Paul de Man, of Barbara Johnson).” Wood’s essay “Shakespeare in Bloom” is the kind of thing that students and aspiring critics alike should read before they feel the need to draw arms. You can read it in the second printing (the first in a decade) of Wood’s essay collection The Broken Estate, which debuts in June, 2010 from Picador.

James Wood, writing about Virginia Woolf in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” (collected in The Broken Estate)–

James Wood, writing about Virginia Woolf in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” (collected in The Broken Estate)–

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says–

In his essay “Shakespeare in Bloom,” critic James Wood performs one of the strangest, most backhanded (and yet earnest) defenses I’ve ever read of Harold Bloom‘s aesthetic reaction to (what Bloom has called) “The School of Resentment” — deconstruction, Marxism, gender and queer theory, postcolonial theory, all that good stuff. Wood comes out strong, arguing, that in his prolific output, Bloom “has kidnapped the whole of the English literature and has been releasing his hostages, one by one, over a lifetime, on his own spirited terms.” Wood suggests that “this ceaselessness has produced some hurried, fantastical, and repetitive work,” before going on to throw around words like “garrulous” and “shallow.” Wood then takes Bloom to task over his famous (and improbable) claim that “Shakespeare invented us,” situating the claim against Bloom’s own most famous theory, the anxiety of influence. Wood says– As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two–

As we bring up the term again, we should note that we consider it a bit pejorative and utterly reactionary, and, to borrow from (and perhaps misapply) Wood, shallow. Wood points out that “Deconstruction brings a generalized suspicion to bear on language and in particular on metaphor (or ‘rhetoric’), which it suspects of hiding something–namely, its own metaphoricity.” In short, literature always metaphorizes, and thus hides, some other impulse, one always politicized. Wood continues: “Political criticism, including cultural materialism, converts Freud’s analytical suspicions into political ones. . . . The poem is read as if it were covering something up, as if it were an alibi that is rather too fluent to be entirely trusted.” It must be interrogated to reveal its secret, the secret prejudices of its age. Wood continues, after a page or two– I’m coming to the end of Hilary Mantel’s brilliant treatment of the Tudor saga, Wolf Hall. Sign of a great book: when it’s finished, I will miss her characters, particularly her hero Thomas Cromwell, presented here as a self-made harbinger of the Renaissance, a complicated protagonist who was loyal to his benefactor Cardinal Wolsey even though he despised the abuses of the Church. Mantel’s Cromwell reminds us that the adjective “Machiavellian” need not be a pejorative, applied only to evil Iago or crooked Richard III. The Cromwell of Wolf Hall presages a more egalitarian–modern–extension of power. Cromwell here is not simply pragmatic (although he is pragmatic), he also has a purpose: he sees the coming changes of Europe, the rise of the mercantile class signaling economic power over monarchial authority. Yet he’s loyal to Henry VIII, and even the scheming Boleyns. “Arrange your face” is one of the book’s constant mantras; another is “Choose your prince.” Mantel’s Cromwell is intelligent and admirable; the sorrows of the loss of his wife and daughter tinge his life but do not dominate it; he can be cruel when the situation merits it but would rather not be. I doubt that many people wanted yet another telling of the Tudor drama–but aren’t we always looking for a great book? Wolf Hall demonstrates that it’s not the subject that matters but the quality of the writing. Highly recommended.

I’m coming to the end of Hilary Mantel’s brilliant treatment of the Tudor saga, Wolf Hall. Sign of a great book: when it’s finished, I will miss her characters, particularly her hero Thomas Cromwell, presented here as a self-made harbinger of the Renaissance, a complicated protagonist who was loyal to his benefactor Cardinal Wolsey even though he despised the abuses of the Church. Mantel’s Cromwell reminds us that the adjective “Machiavellian” need not be a pejorative, applied only to evil Iago or crooked Richard III. The Cromwell of Wolf Hall presages a more egalitarian–modern–extension of power. Cromwell here is not simply pragmatic (although he is pragmatic), he also has a purpose: he sees the coming changes of Europe, the rise of the mercantile class signaling economic power over monarchial authority. Yet he’s loyal to Henry VIII, and even the scheming Boleyns. “Arrange your face” is one of the book’s constant mantras; another is “Choose your prince.” Mantel’s Cromwell is intelligent and admirable; the sorrows of the loss of his wife and daughter tinge his life but do not dominate it; he can be cruel when the situation merits it but would rather not be. I doubt that many people wanted yet another telling of the Tudor drama–but aren’t we always looking for a great book? Wolf Hall demonstrates that it’s not the subject that matters but the quality of the writing. Highly recommended. Cromwell’s greatest foil in Wolf Hall is Thomas More, who is also the subject of the first essay in James Wood’s collection The Broken Estate. I got my review copy in the mail late last week, so it was pure serendipity that I should read “Sir Thomas More: A Man for One Season” after a full day of listening to Wolf Hall (did I neglect to mention that I listened to the audio book? Sorry). Wood is harsher on More than Mantel; whereas she lets us despise him within the logic and framework of the Tudor court, Wood aims to find a contemporary secular standard from which to judge him. He finds license to do so through the work of John Stuart Mill, citing the influential essay On Liberty. Wood writes:

Cromwell’s greatest foil in Wolf Hall is Thomas More, who is also the subject of the first essay in James Wood’s collection The Broken Estate. I got my review copy in the mail late last week, so it was pure serendipity that I should read “Sir Thomas More: A Man for One Season” after a full day of listening to Wolf Hall (did I neglect to mention that I listened to the audio book? Sorry). Wood is harsher on More than Mantel; whereas she lets us despise him within the logic and framework of the Tudor court, Wood aims to find a contemporary secular standard from which to judge him. He finds license to do so through the work of John Stuart Mill, citing the influential essay On Liberty. Wood writes: