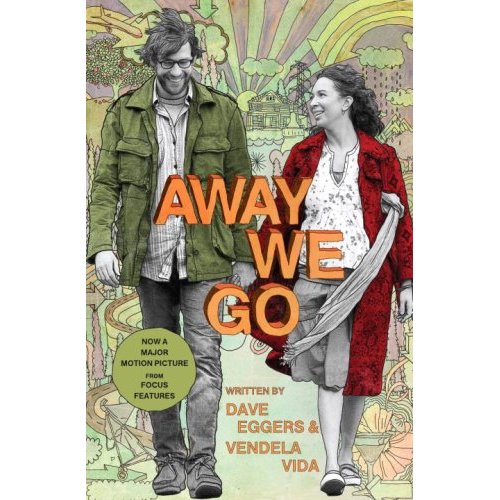

Away We Go is the story of Verona and Burt, an unmarried couple in their early thirties expecting a child. After discovering that the child’s only living grandparents will be moving to Belgium, Verona and Burt realize that there’s nothing anchoring them in Colorado. The pair set out on a cross country journey in their boxy old Volvo, meeting up with old friends and family in an attempt to find the right place to start their new family.

“We’ve attempted to make this readable to a non-screenwriting population, from whose ranks we’ve recently come,” write Dave Eggers and Vendela Vida in their introduction to their screenplay for Away We Go. Released last week in conjunction with the film, the screenplay, with its vivid cover and prestige trade format, seems to physically back up Eggers’s and Vida’s wish–they’re hoping that you’d want to, y’know, actually read it, like, a book, and not just watch Sam Mendes‘s filmed version. There’s that hopeful, informative introduction, for starters, and they really do make good on their claim of readability; stage directions and location shifts are clear but never overbearing, allowing the reader to engage the characters in his or her own imagination. The book also includes scenes (apparently) cut from the movie–should I mention now that I haven’t seen the movie?–as well as an alternate “admittedly radical Bush-era ending.” Still, it is a screenplay–not a novel, not a play, but a text intended for a movie, a movie out there getting reviewed now, a movie with physical entities playing the key roles. “Verona and Burt were written with Maya Rudolph and John Krasniski in mind,” Eggers and Vida state in their introduction, and, between this admission and press for the movie, its almost impossible to read the script without imagining these actors’ mannerisms and tics. Not that that’s a bad thing, it just limits any nuance in (and in between) the lines, and again brings up the question of why one might want to own this book.

The answer for many readers, of course, will simply be Eggers, a modern literary luminary. For the record, we’re a huge fan of Dave Eggers, even when his writing isn’t the best. Eggers is perhaps the most visible of a whole crop of post-David Foster Wallace writers (for lack of a better term), a linchpin of a (non-)movement whose literary house McSweeney’s, and its attendant magazines, Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Believer, and the video journal Wholphin frequently feature some of the best writing and art out there today. His 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius might be a bit overrated, but it’s also one of the first post-DFW books to grapple with irony and earnestness in a moving discourse. Besides all of that, Eggers is the founder of 826 National, a nonprofit organization that tutors kids in writing and reading across the country. In short, Eggers is all about making reading and writing fun and cool and demystified for lots and lots of people, and because of that, he’s a hero of ours. Of course, he has his haters; there are many who claim that McSweeney’s is form without substance, all show, fancy design without good writing. This is a pretty silly argument, because all you have to do is sit down with an issue of McSweeney’s or The Believer and actually, y’know read it to realize that 99% of the writing is fantastic. Better yet, check out one of the books they’ve published, like Chris Adrian‘s The Children’s Hospital. Eggers’s haters generally don’t have a lucid argument because what they hate is an attitude, a vibe, a feeling. I’ll readily admit that I’m hip to what they’re describing, and something of that backlash has come out in reviews of the film–especially New York Times critic A.O. Scott’s overly-analytical takedown of Away We Go. There’s a preciousness, a smug quirkiness, an awareness that people simply do not have discussions in the manner that Verona and Burt do, and this puts people off. Of their fictional parents-to-be, Eggers and Vida–who were pregnant with their own child October when they wrote the screenplay–write: “When we conceived them, we thought of a couple who was as different from ourselves as we could muster.” People who read into things deeply might find it hard to believe that Verona and Burt are anything but stand-ins for Vida and Eggers, and that couples casual resistance to the extreme drama of having a child is, honestly, a bit offputting. (If you really want to see some visceral Eggers-hating/Eggers-defending, check out the comments on this recent A.V. Club interview with the pair).

But back to the screenplay, which I suppose was the occasion for this writing. I enjoyed it. It was funny. At times there was an irking quirk to the characters, a certain shallowness that doesn’t do justice to the intensity of pregnancy. I read it in two short sittings–less time than the film would take to watch, I suppose. It also made me want to watch the film, rather than putting me off. Eggers completists might want to add the screenplay for Away We Go to their collections; newbies interested in his work should check out his novel What Is the What, Eggers’s remarkable novelization of the life story of Valentino Achak Deng, one of the “lost boys” of Sudan.

Away We Go is now available in trade paperback from Vintage.