Fifty Shades of Louisa May by L.M. Anonymous, is , to all appearances, the kind of cheeky send-up that E.L James’s Fifty Shades of Grey hardly deserves. Satire has the strange, paradoxical power to somehow dignify its target after all, or at least point out how the thing being satirized is, you know, worth actually talking about. However, Louisa May has no proximity to Fifty Shades of Grey, other than the window dressing of its cover and its title, both of which exist somewhere on the thin line between clever and crass. Sure, Louisa May has its share of sex scenes (most are more ridiculous than erotic), but this slim little book is, at its core, really a loving biography of novelist Louisa May Alcott.

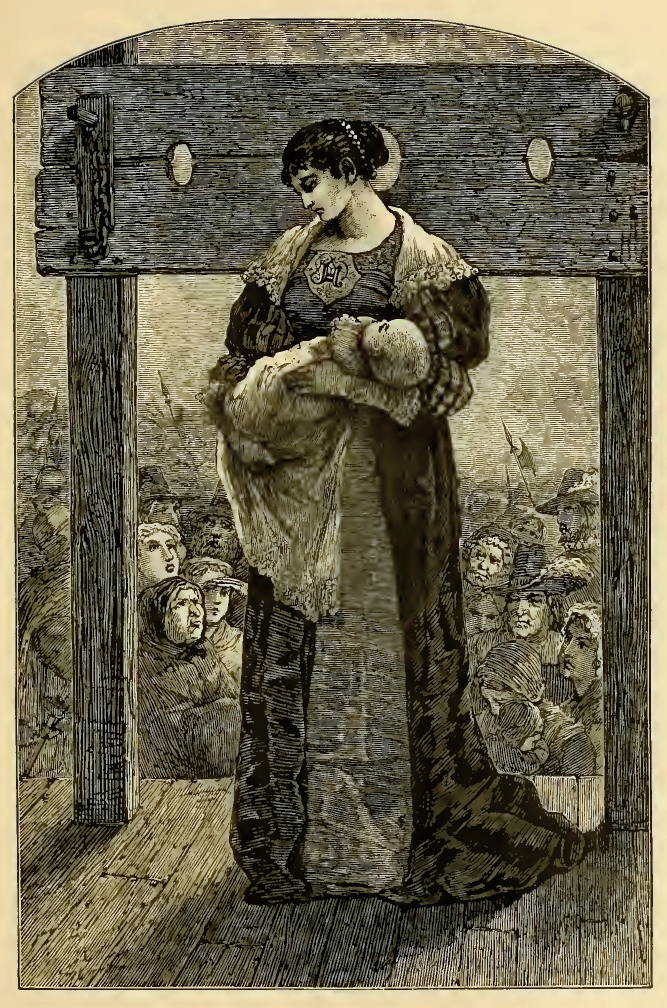

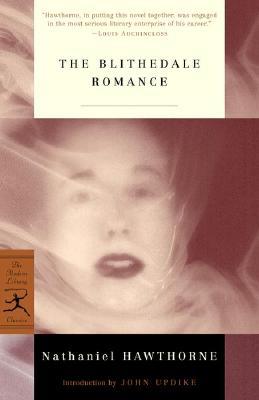

The conceit is that Alcott, dipping into her secret vice of a midnight bottle of Madeira, decides to a pen a memoir (that she intends to burn) of her “carnal episodes, some amusing, others touching, but all rife with the sighs and heavings of Love’s labours.” (How the “X-rated woodcuts” that accompany each chapter made their way into the book remains unclear; I suspect that they follow the tradition established in the mashup Pride and Prejudice and Zombies). Organized roughly around Alcott’s difficult life with her transcendentalist parents and their transcendentalist friends, each chapter of Louisa May culminates in an erotic episode, albeit one that our heroine usually witnesses as voyeur and not participant. These episodes tend to involve other transcendentalist figures. In one inspired vignette, Louisa May sneaks out of her house to follow Herman Melville to the Old Manse, where she watches him watch Sophia and Nathaniel Hawthorne get it on:

I heard a small groan from Mr. Melville’s beech tree and saw that his own garments now circled his ankles and he was busily engaged in the art of Onan, his slitted eyes on his mentor, beard shivering with concentration. I looked away quickly—even in my youth I knew that such solitary activity must remain unwitnessed.

The Hawthornes let out a quivering scream, Nathaniel’s voice as high pitched as his wife’s as he rose from his chair to finish the work that his wife had begun. Thus spent, Sophia lay back in his arms. The ever-fastidious Mr. Hawthorne reached out with one hand to set to reordering his manuscript pages.

Mr. Melville let out a low hoot and sent a frothy fusillade across the yard to strike the windowglass with a furious splash.

“Look, my Dove, it appears to be raining,” Sophia said.

The episode is obviously more comical than erotic, its style—indeed the style of the entire book—a strange mashup of Alcott’s own rhythms and the diction of Victorian smut. There’s something joyously silly in the way L.M. Anonymous throws together various transcendentalists into would-be erotic interludes; when our heroine describes Fruitlands founder Charles Lane jacking off by moonlight, the whole thing feels like a big dirty in-joke for those of us who love this period of American history and literature. And sure, the jokes can be very crude—here’s Henry David Thoreau, nature lover:

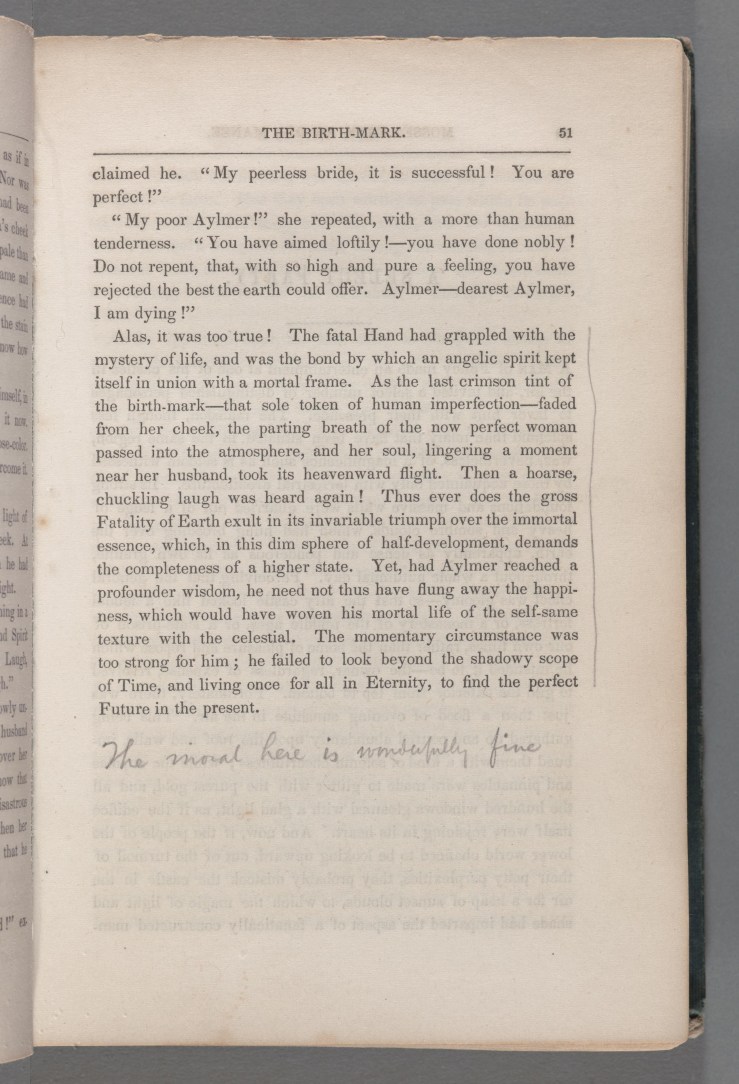

L.M. Anonymous (“a well-known writer who prefers the cloak of anonymity to the vulgar embrace of rude fame,” according to the back of the book) seems to know his/her history (and attending rhetorical styles) fairly well. I’d have to guess that the author is, if not an Alcott scholar, then at least a passionate enthusiast—because what stands out most about Fifty Shades of Louisa May isn’t the smut but the internal conflicts of our narrator Louisa May.

In Anonymous’s imagination, Alcott is an embittered soul who has never forgiven her father for his foolishness, nor gotten over the fact that she’s the sole source of income for the Alcotts. She badmouths her books as unserious trash, bemoaning that she could do more:

Too often I have found myself diminished by the company of Famous Men to praise them. Had I been but relieved of the burden of supporting the entire legions of Alcotts with my earnings, I could have written novels and poems to equal their best—of that I am most confident. Instead of greatness, I lingered at the Trough of Rubbish too long, achieving only a shining of tin, not the glimmering of gold. But it is too late for me to be concerned with such matters. Time sorts out all writers, revealing each for what they truly were. I only hope that I shall be remembered as much for what I did not achieve as for what I did.

There’s so much tenderness here: Anonymous’s love and respect for his/her subject is plain. The author also seems to write through the book, through the narrator in this passage, as if acknowledging, in some metatextual move, the book’s own novelty status, pointing out that the book, a shaky Grey cash-in, is in some way a part of the Trough of Rubbish, but also that there’s more here too.

I read Fifty Shades of Louisa May in one short sitting, and found it at times amusing, if not especially erotic. I was prepared to to write it off as a silly novelty book—which perhaps it is—but there’s also a real love—and understanding—for Louisa May Alcott that comes through here. Who is it for? I’m not really sure. I’m going to guess that Fifty Shades of Grey fans will be disappointed, and fans of Little Women and its sequels will find their beloved tome trashed by Alcott herself (or at least her character). The book might work best as a primer to the American Renaissance, although I’m not sure which professor would be brash enough to stick this on her syllabus. My hope would be that Grey fans might find in Louisa May an inroad into better writers; at minimum though, they’ll at least be exposed to prose far superior to E.L. James’s trough of rubbish.

Fifty Shades of Louisa May is new in trade paperback from OR Books.